A quotation that some attribute to the famed bandmaster John Philip Sousa goes something like this: “Teach a boy to blow a horn and he will never blow a safe.”v1

The founders of the Alabama Boys’ Industrial School certainly agreed with that principle. From the beginning of the institution, the creation of a concert and marching band was on the agenda. Over the next fifty years, this tousle-haired, rag-tag assortment of boys would become one of the finest bands of its kind in the country, to make even Sousa proud.

The notion of a musical band in a correctional facility seems out of place today, but the innovative warden Zebulon Brockway had implemented this rehabilitative concept at New York’s Elmira Reformatory in 1876.2 It is not known where the ABIS leadership got the idea, but C. D. Griffin, the first superintendent, referred to such a plan in the institution’s third annual report in 1903.

“One of the most attractive and most useful departments in an institution like ours is the Band,” Griffin stated. “It keeps the boys interested, teaches them to read music and may be made a source of profit as well as pleasure when they leave us and strike out for themselves. There is always a chance for a good musician to make money enough for expenses in a new place while looking for something in a band or orchestra.”

Dealing with the bleak situation of keeping the new school afloat, Griffin obviously found it difficult to fund a nonessential activity like a band in the midst of more pressing needs. So, his wife came up with a novel idea. “We have a wild plum orchard that yields us an abundant supply of plums annually. Mrs. Griffin devised a scheme whereby a Band Fund could be started by making our surplus plums into jelly for sale,” Griffin wrote. “It seemed a good idea and the ladies of the Board thought the product could be disposed of to advantage, so the fruit was picked by the boys and worked up into jelly at night after the boys had retired. There were about 800 glasses made, the ladies of the Board selling what they could at $2.50 per dozen glasses.”

The band finds a shady place on campus to practice.

Apparently plum jelly was not in high demand that season, for the results of that effort are never mentioned. However, one of the school’s supporters, a Mr. F. M. Jackson, took up the cause and raised $218 for the band. Mr. Griffin was then able to purchase twenty-two used instruments for $200 [$5,263 in 2013 dollars], a fact that greatly pleased both him and the boys. “Our boys are already enjoying in imagination the fine music we are to have some months in the future when they have learned to use their instruments,” Griffin reported. His tenure with the school lasted only an additional year, so he was not on hand to see these musings turn into music.3

Griffin’s successor, Weakley, was an ardent supporter of the band. When he took the helm in 1905, he immediately took action to move the project forward. His was no easy task, either. Not only did he battle financial realities, but he met with resistance from those who opposed such a program in a school for delinquent boys. “To my surprise, I experienced much opposition from some of the public school teachers,” Weakley wrote in his papers some years later. “One Superintendent of Public Schools was outspoken in opposition. In fact he was so antagonistic that I feared for awhile that public opinion would be so wrought-up that I would have to abandon the project.” This opponent went on to say that such an enterprise would be “corrupting and disrupting to the whole educational system; that the boys should be taught to work and should not be exposed to such falderal.”4

Weakley was quite eloquent in his defense of music. The purpose of musical instruction was “not to turn out professional musicians, but to develop an inner response in the heart and minds of our boys to the finer, higher things of life. I believe,” Weakley continued, “in the spiritual, mental, and moral exaltation it creates, and the nobility of its influence in correcting and improving human behavior, especially in the lives of the young. It seems to me, that music is a potent force in helping to curb and, perhaps, cure crime.” Weakley went on to quote great thinkers who lauded the healing powers of music. Plato, he said, praised “the rhythm and harmony [that] find their way into the inward places of the soul . . .” Shakespeare wrote that “the man who hath not music in his soul . . . is fit for tragedies, treasons, and spoils.”5

Weakley’s arguments eventually convinced the local school official and everyone else, for the band became a reality within a year of his arrival. Some reports indicate that ABIS was the first school of any kind in Alabama to have a band.6 Initially the band started with fifteen students with Weakley, who had played in bands himself in his youth, as the instructor.7

Soon thereafter, John D. Henderson was employed as the school’s bandmaster, but he also had to serve as the school’s shorthand and typewriting instructor. In his initial report as bandmaster, Henderson wrote of the accomplishments and challenges of working with the new band. He also gave a not-so-subtle commentary on Griffin’s purchase of those first instruments off the clearance rack. “I regret to say that our original twenty-two instruments were bought by an inexperienced man, and while the intentions were good, they could not be considered a bargain at any price, as their musical qualities, and not their weight in brass, should have been taken into consideration.” The fine musician was not deterred, however, for within six weeks the band was already playing some simple compositions.8

Colonel Weakley was not the only one to extol the benefits of the band for the students and the school. In her portion of the report, Mrs. Johnston noted that “a boy failing in good conduct is suspended from the band, making this not only a source of pleasure, but also a means of discipline.”9 Henderson commented that all schools need a “time for recreation, both physically and mentally.” He also wrote of its “educational and pecuniary advantages” and of its “effective method of bringing the School and its work before the public . . .”10

A couple of band members look very serious about their music.

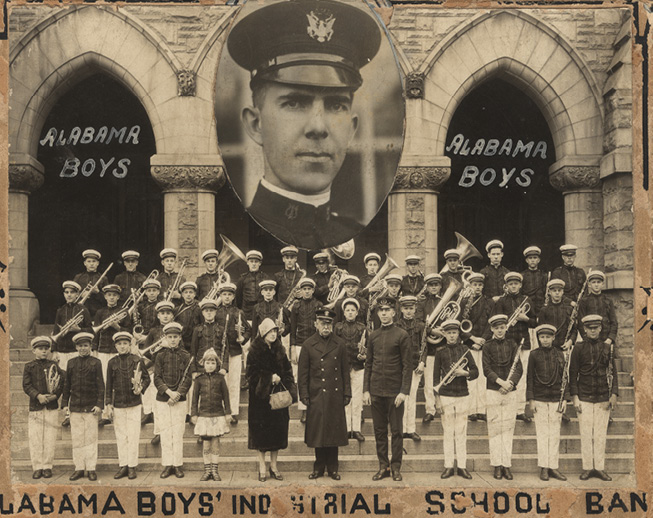

This publicity photograph shows the band during one of John Philip Sousa’s appearances in Birmingham. The adults in front are, from left to right, Mrs. Johnston, Sousa, and ABIS band director E. C. Jordan. Captain Jordan’s picture is also shown in the inset at the top. The photo was taken during World War I when Sousa served as a lieutenant commander and led the Naval Reserve Band in Illinois.

So, go before the public they did. Their skills developed to such a level in their first year that they were selected to lead the parade when President Theodore Roosevelt paid a visit to Birmingham. Later that day they paraded by the president’s reviewing stand decked out in Rough Rider uniforms in his honor. When someone whispered to him “There come Mrs. Johnston’s boys,” the president clapped his hands and shouted his trademark “Bully, Bully!”11

If it is possible to go any higher than performing for the president of the United States, this group did it over the next forty years. After several years, Henderson left to assume another position and was replaced by Eugene Jordan. Under Jordan’s twenty-five year tutelage, the band’s fame spread throughout the nation.12 Over the years, the band made several appearances in Washington, D.C. They gave a performance in front of the Capitol, and also accompanied the U.S. Marine Band in concert in one of the city’s parks.13 In 1922, the band went on an extended six-week trip on the Keith Vaudeville Circuit through Tennessee, Arkansas, and Texas.14

The band, averaging sixty members, was a “must” at any event and parade in Alabama. The 1931 Annual Report shows the band made fifty-four appearances that year alone, ranging from the Howard College vs. Birmingham-Southern football game to the Ruhama Baptist Church service to a Lions Club luncheon. They made a broadcast on WAPI radio, played at the season-opening baseball game at Rickwood Field, serenaded the First Methodist Church, and gave a concert at the Old Soldiers Reunion in Montgomery. They played for the Ice Cream Manufacturer’s Convention at the Tutwiler Hotel, in the Better Business Bureau parade, and at a function for the LeHigh Cement Company in Tarrant City.15

With as many trips and engagements as these boys had, a few memorable occurrences were bound to happen. One such incident happened during an engagement in a neighboring city. Jordan was leading the band down the street when he was approached by a small boy.

“Say, mister, how can you get in this band?” he asked.

“You shouldn’t worry about getting into this band,” Jordan simply replied.

A few blocks later the boy appeared again and said, “I want in this band. How can I get in?”

“Run along, son. You see I am busy,” Jordan gently told him. However the boy persisted and asked again.

“Just break out some windows,” the bandmaster said jokingly just to get rid of the tyke.

A few months later back at the school, a youngster met Jordan on the sidewalk. The boy saluted and said, “Well, here I am.”

“Who are you?” asked Jordan.

“I’m the boy you told to break out some windows,” the new student answered.

“Oh, son, you didn’t really do that, did you?” Jordan sighed.

“Yes, sir, I did, and I like to never have made it. Some of those welfare ladies would beg and ask for another chance. I finally had to break a plate glass window before I made it,” he proclaimed proudly.

Since he had merely taken Professor Jordan’s advice, they just had to let him in the band.16

Colonel Weakley once had the opportunity to provide some needed guidance to one of the band members. The student’s school work had declined, and the colonel stopped by to see about the problem. “Colonel, I’ll be plain with you,” the boy finally confessed. “I’m in love.” He then explained that while the band had been on a recent trip to Anniston, he had fallen for a young girl with whose family he had stayed on the overnight trip.

“Well, I’ve never known it to kill a man, son,” Weakley advised. “But if you’ve really got it bad, maybe you’d better learn to make enough money to afford a wife.” The young man did just that by learning to be a typesetter. Two years later, the couple married and moved to North Carolina, where he took a job with a newspaper.17

The band had one other case of puppy love. Weakley recalled in his papers a collie named Corporal that came to live at the school. He became every boy’s pet, and was therefore terribly spoiled. Corporal was especially fond of the band, went to their practices, and followed them when they rehearsed their marching.

One day the band was giving a performance a few miles down the road in East Lake. In the middle of one of the numbers, Corporal came bounding down the center aisle and tried to jump on the stage with the band. The stage was so high that only his front legs reached the platform, leaving the remainder of the concert-loving canine dangling in the air, howling along with the music. Without missing a beat, the director leaned down and pulled Corporal up, where he stood at attention for the remainder of the show.18

Through the years, the ABIS Band received plaudits from the Kiwanis and Rotary clubs, commendations from several chambers of commerce, and favorable comments from editorials in the Montgomery Advertiser and the Birmingham News, to name a few.19

Perhaps their biggest fan was the man whose stirring marches they could play by heart, John Philip Sousa. The great bandmaster and composer came to Birmingham for a performance, and the boys were a part of the welcoming party.20 The famed maestro directed the band during the intermission of his concert, and presented them with his prestigious Loving Cup.21 At the conclusion, he shook hands with the boys, posed for pictures and complimented them as possibly the finest boys’ band he had ever heard.22

Undoubtedly Sousa also recognized that as well as these boys could blow a horn, the safes around Birmingham were in no danger.

1 Weakley, 65.

2 Harry E. Allen, Edward J. Latessa, and Bruce S. Ponder, Corrections in America, 12th ed. (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 31.

3 ABIS reports, Fourth Annual Report (East Lake: Alabama Boys’ Industrial School, 1904), 8-9.

4 Weakley, 64.

5 Ibid., 64-65.

6 Woodlawn-East Lake News, “Boys’ Industrial School Great Asset in Training State’s Misguided Youth,” February 8, 1946.

7 Weakley, 64.

8 Sixth, 44.

9 Ibid., 5.

10 Ibid., 43-44.

11 Avery, 73.

12 Weakley, 69-70.

13 Ibid., 68.

14 Ibid., 72.

15 Thirty-First, 27-31.

16 Weakley, 72-73.

17 Rankin.

18 Weakley, 203-204.

19 Ibid., 75.

20 Thirty-First, 30.

21 Weakley, 74.

22 Avery, 73.