The demands of tending to the medical needs of one’s own child can make a parent anxious enough. Try looking after the welfare for upwards of 450 boys at one time, and it can be downright frightening. That was what faced the staff of the Alabama Boys’ Industrial School, and if the gravity of that responsibility had not hit home immediately with Elizabeth Johnston and her sister board members, it soon would.

At the beginning, the boys’ healthcare did not seem to be a major issue. A local physician, Dr. J. N. Killough, volunteered to attend to most of the school’s medical needs at no charge. Any major illnesses or injuries were handled by taking the boys to one of the local hospitals. This tranquility did not last for long, as the third year brought a change of fortune. Mrs. Johnston wrote the governor:

It has been a much more trying year than either of the preceding years.We have been called upon to chronicle our first death. Mason _______ was taken with fever; at first it seemed to be malarial, but developed into typhoid. After several weeks of sickness, during which he was carefully nursed, he died and was buried at Woodlawn.

Quite a few of our boys were sick for a number of days, and two more occupied our sick room for four weeks. Three more were cared for at the hospital for two weeks. Dr. Killough, our faithful physician, came at our call night and day without any compensation other than a consciousness of doing good where his services were greatly needed.”1

The physical condition of the students was good during Colonel Weakley’s first year (1905). “The general health of the pupils has been excellent, and we are truly thankful the grim visitor of death has not, by his appearance added any gloom of sorrow to our home. There have been no contagious diseases of any kind; in fact, it has not been necessary to call in our physician but once during the entire year, then it was a case of biliousness.” This term, popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, could best be described today as an upset stomach.

“We attribute this excellent record to Providence, the strict habits of the children, and the watchful care of their teachers and instructors,” he continued. “There is much that can be done in a sanitary way to further insure the health and well being of the School in general which should be given more than passing attention. Lack of funds has prevented us from making these improvements.”2

Those words proved prescient the very next year (1906) as typhoid fever struck the campus. Weakley told of their ordeal in his remarks to the board:

During the latter part of July one of the boys was so unfortunate as to contract a case of typhoid fever, from which we soon experienced quite an epidemic, fifteen boys in all taking the fever, beside a number of others who were sick at the same time, swelling the number to about twenty-three. This sickness was a great surprise to the school officers and members of the Executive Board, for the hand of Providence had safely guided the whole school through a year and four months of splendid health, necessitating calling our physician only once during the entire time, and as a consequence, we were not prepared in any manner for the terrible siege we were destined to undergo. Then, too, the fact that we had no hospital facilities, no place to isolate the patients, and our plumbing and sewerage system in very bad shape, added horror and complexity to our position.3

In her comments to the governor, Mrs. Johnston also showed the anguish from the situation:

From this wave of prosperity we were plunged almost without warning into an epidemic of typhoid fever. Four of our teachers left in one week; Mrs. Weakley and child were ill, and with only one man and two lady teachers, Mr. Weakley was absolutely at the mercy of the boys, and I trembled for our work. But the foundation had been well laid, close and firm, and the boys rose to the occasion and asked to be placed in the positions made vacant by retiring officers; they carried on the work of the institution until we could reorganize and secure more aid. With fifteen cases of fever, the incomparable fact remains that we did not lose a boy, and stamped out the epidemic in about five weeks. Dr. Killough was most acceptable as a physician and states that his success was largely due to the fact that the sick boys were absolutely obedient to his orders.”

One tragedy from the epidemic deeply touched the institution—and Mrs. Johnston. “Death, the relentless one, did not pass us by, but took the lamb of our flock, little Mary Fryer Weakley, the most beloved member of our household. She has gone to that School where Christ Himself doth rule and we know it is well with the child.” The child was Colonel and Mrs. Weakley’s three-year-old daughter.4

In Weakley’s own remarks about the loss, his immense grief was apparent, but also his abiding faith:

The Great God in his wisdom did not deem it best to take one of these boys, but an Angel of the Darker Hue visited our own family circle, and after six weeks of patient suffering our dear little girl, the light of our lives, was gathered to her Father in that Celestial Home not made with hands. And now while we mourn for her and her glad winsome smile; and shouts of merry laughter will never cheer us more, we would not have her return, for she has finished the journey and paid that debt all mortals must pay—death. And though our days here may be few or many, we know that just beyond the calm, enrapturing vista of eternity, small hands are beckoning us, and an invisible voice is entreating us to so live that after our eyes are closed in death, and we have laid our wearied selves down to take that last sleep, that we must not go in fear and trembling like a galley-slave, but to believe that as we journey from the finite to the infinite—from the measurable to the immeasurableness—that when the scintillating sheen that veils the Great Beyond is gently lifted by the hand of Omnipotent, that there shall suddenly burst on our blinded visions the Great White Throne of God; and once again we shall be face to face with her we loved so well.5

The tenth year of the school was also beset with some medical issues, but none as catastrophic as before. “This has been the record year so far as acute sickness,” Dr. Killough reported. “There have been light epidemics of measles and La Grippe (the flu), but no deaths resulting from either. One patient developed tuberculosis after a relapse of measles, but probably had incipient tuberculosis before taking the measles. We have had only one death, that from appendicitis. The above, with the exception of minor cases, covers all our sickness for the past year.”

Dr. Killough also touched on preventive measures that should be employed. “I do not know of anything more conducive to good health and pleasure than the cold shower baths that are now given before retiring, and recommend a continuance of same. Special attention should be given to clean hands and face, and would insist that finger nails be kept cut short, for I am sure abcesses of neck and scalp have been to a great extent produced by scratching with infected nails.” Dr. Killough also echoed a call first made by Colonel Weakley several years earlier to build a small hospital to serve the campus.6

That plea was answered when the second floor of the Johnston Building was converted into a hospital ward, with two private rooms and a small operating room. Over the years, a dental clinic was added, along with whatever medical equipment the school could afford.7

The hospital would be overwhelmed by the 1918 influenza epidemic that hit the nation, including Birmingham and the Alabama Boys’ Industrial School. Approximately 100 cases were recorded at the school from students and employees. Unaffected students as well as community volunteers helped to care for the sick.

One of those community volunteers, Corinne Chisholm, was a writer for the Birmingham News. Her admiration for the boys was obvious in the article she wrote about her experiences:

It has been my privilege in the week just passed to become acquainted with many of the boys of the Alabama Industrial School at East Lake, and let me tell you, I have never in my life met a more mannerly or more appreciative bunch. I went out there to help in the hospital while so many were sick with influenza, so I know the sick boys as well as the well boys. It is hard to tell which are the finer. About twenty of the well boys are working in the hospital, keeping things clean and waiting on the patients and the nurses. They work twelve or fifteen hours a day without complaint and never have to be told anything twice. Almost overcome one night by my amazement at the thoughtfulness and efficient helpfulness of the boys, I exclaimed, ‘Are there any bad boys out here?’ At that, the youngsters burst into gales of laughter, and that was the only answer I got. The sick boys never complain and our chief concern is to find out what they want. There are many long rows of beds full of boys, none of whom, I’m happy to say, is dangerously ill.8

An ABIS student prepares for an examination while another waits his turn.

These before and after photographs demonstrate the result of corrective surgery on a cross-eyed ABIS student.

Despite Chisholm’s optimistic assessment, death did touch the student body again due to the epidemic, although incomplete records do not pinpoint the exact number of victims.

All was not life and death at the hospital. As one would expect with a school full of boys, there were the normal childhood illnesses and injuries. An exhaustive report from 1930–31 lists measles, mumps, chicken pox, hookworm, tonsillitis, hemorrhoids, constipation, trench mouth, burns, lacerations, and sprains. Also recorded was the removal of a needle from a boy’s knee, with no explanation of how the needle got in the knee.9

The medical program at the school was not limited to responding to crises. Colonel Weakley and his staff prided themselves in being proactive, especially in regard to how physical conditions might impact behavior. In his papers, Weakley told of an operation performed on a young man with a double harelip, and how the success of that procedure dramatically changed the boy’s personality and improved his school work. One boy had his crossed eyes properly aligned. Another student had several operations in the school’s hospital to correct his clubfeet and enable him to walk normally. The youngster’s delight with his new mobility led him to train in shoe repair at the school and open his own shoe shop in his hometown upon release.10

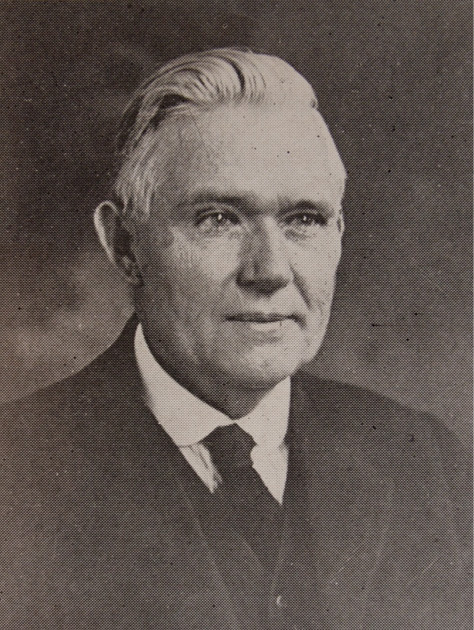

Dr. J. N. Killough served ABIS for 25 years with little or no compensation. Numerous specialists in the Birmingham area also donated their services.

Such sophisticated operations were performed by some of the leading surgeons and specialists in Birmingham. Dr. Killough was so respected that he was able to enlist the best in the local medical community to donate their time and talent. Not the least among these benevolent physicians was Dr. Killough himself.

Weakley talked about the dedication of his friend and colleague at the time of the doctor’s death:

For over thirty years, Dr. Killough visited this school almost daily. In the early years when the school was struggling for existence, he gave his time, himself, and his energy without charge to relieve pain and suffering. Before the school was able to employ a trained nurse, Dr. Killough spent many nights in lonely vigils by the bed of some desperately sick boy. He was more than a doctor; he was a family physician; a healer of the body and soul.11

1 Third, 2-3.

2 Sixth, 27.

3 Seventh, 8-9.

4 Ibid., 2-3.

5 Ibid., 9-10.

6 ABIS reports, Tenth Annual Report (East Lake: Alabama Boys’ Industrial School, 1909), 30-31.

7 Weakley, 135.

8 Ibid., 43-45.

9 Thirty-First, 40-44.

10 Weakley, 47.

11 ABIS reports, Thirty-Second Annual Report (Birmingham: Alabama Boys’ Industrial School, 1932), 9-10.