If someone had been at the helm of a home for mischievous boys for nearly half a century, it is a pretty safe bet he would have some stories to tell. Well, David Weakley certainly did, and he shared many of them in his personal papers. Some of the stories are humorous and provide a glimpse of the day-to-day life supervising hundreds of boys, while others are inspiring and give some idea of the simple rewards Weakley received from his lifelong undertaking.

Several of Weakley’s favorite stories are linked by a practice that is still common even in today’s correctional institutions. “Most boys at the school were usually given a nickname soon after arrival—sometimes in a matter of hours,” he wrote. “It was usually based on appearance, stature, mannerism, or some unusual characteristic that was obvious.”1

As an example, Weakley told of one boy from Mobile who entered the school one afternoon, and had earned his nickname before supper. It seems this new student considered himself somewhat of an authority on any subject, and did not mind sharing his knowledge whether it was requested or not. The boys soon dubbed him “Windy.” The loquacious young man later became, quite fittingly, a radio announcer.2

Weakley described another youngster, whom his cohorts tagged as “Grasshopper,” as being “jumpy, ever on the move—not mean—but a genuine nuisance.” One day one of the feisty student’s teachers came into Weakley’s office to voice a little of her frustration with Grasshopper. As she plopped down in an inviting chair, she told her kindly boss of a recent revelation. “Mr. Weakley, I believe in the Bible more and more every day. You know I have Grasshopper in my class, and the Bible says, ‘The Grasshopper shall become a burden,’ and he is, and the prophecy has not failed.”3

Another young man got his nickname out of his desperation. The boys, of course, were not allowed to have tobacco, yet a few of the fellows always seemed to have a little tucked away somewhere. A new resident at the school, a tall, lanky teenager from the country, had not yet learned how to acquire the precious commodity. One day he saw another student with a plug of tobacco and began begging for a share. After repeated rejections, he finally pleaded for his classmate to please give him just a “smidgen,” and in so doing, earned a nickname that would last for years.4

The superintendent received a visitor on one occasion who was very interested in the nicknames the boys doled out to their mates. The lady was a professor of psychology at a noted university, and she was researching what she believed to be the negative, stigmatizing effects of nicknames within institutions. She believed that the use of such names was severely damaging to a youngster’s self-esteem and should not be allowed in such a facility. Weakley admitted in his papers that he was somewhat skeptical of her theory, but tried to placate the professor by assuring her that the use of nicknames at his school was minimal and certainly not harmful. The guest seemed quite pleased and promised Weakley that she would mention his school and its enlightened leader in her upcoming book.

After some further discussion, Weakley’s caller got up to leave. As Weakley escorted her to the door, a little boy entered the lobby. The professor greeted him warmly, patted him on the head and remarked, “Why young man, you must be the smallest boy in the school.”

“Naw, ma’am,” the boy replied politely, “ole Pole Cat is littler than me.”

With some chagrin, Weakley confessed in his papers that the school was probably not mentioned prominently in her new book after all.5

Weakley recalled another visit from a college professor that had a much more positive ending. The woman was a faculty member at renowned Columbia University and she came to Birmingham specifically to meet the longtime superintendent and to see his school. One of her former students had been a resident at the school and had told her of an object lesson that Weakley had once used that had helped mold the young man into the disciplined learner he became.

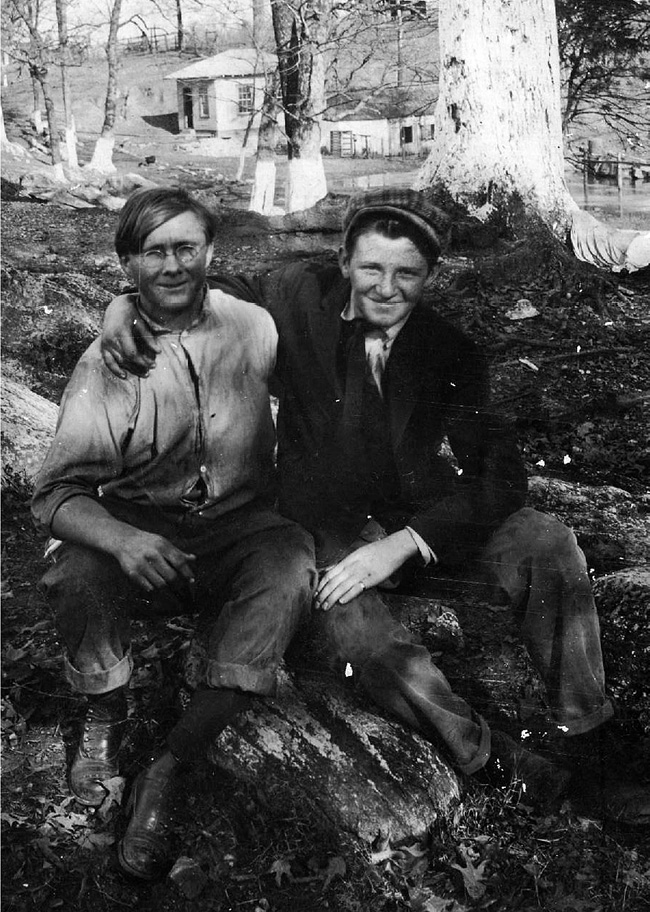

These two ABIS students, pictured near the spring that supplied the campus with water, were no doubt typical of the hundreds that passed through the school during Colonel Weakley’s tenure. Their stories could range from the comical to the tragic.

A boy’s day was filled with school, vocational training, work, military drill, and athletics. These boys also found a little time for relaxation.

The young man had always been bright and studious, but somewhat careless in his habits and badly in need of a little dose of responsibility. One afternoon he had been sent to the woods to cut some firewood and when he had finished his chore, he left behind the crosscut saw he had been using. Weakley sent him to retrieve it and ordered that he keep it in his possession until he told him otherwise—the saw was to accompany him to school, to the dining hall, to the playground, and even to bed at night. When the boy eventually left ABIS, he entered Columbia and had an outstanding record. The professor had complimented her student on how painstaking he was in his work, and he told her the story of the saw.

As Weakley talked with his protégé’s professor, he sheepishly conceded that his methods might not meet with most educators’ approval. She kindly told him, “I wish more of my boys had carried crosscut saws.”6

Some of Weakley’s stories carried no such moral but give a heartwarming picture of the innocence of the times. One boy sent to the school from a rural area could neither read nor write. One day he received a letter from his girlfriend back home, but he was at a quandary as to how he could get his true love’s message given his inability to read. He finally arrived at a brilliant solution: “I’ll give you a nickel to read the letter,” he told one of his classmates, “but you will have to let me put my fingers in your ears so you can’t hear what she says.”7

A group of boys decided one day that they likewise would not let a minor problem deter them. Mr. and Mrs. Weakley had made a quick trip into the city, and the boys were left behind to cook some stew while the couple was away. A large caldron was simmering on the wood stove, when the flue came loose where it connected to the ceiling. One of the boys decided to put the paddle they were using to stir the stew across the top of the pot so he could stand on it to reach the flue. As he carried out this delicate procedure, his foot slipped on the greasy paddle and he fell into the boiling stew. Thankfully, his boots and military leggings prevented serious injury.

When the Weakleys returned, one of the tykes ran to meet them with the news of what had happened during their absence. After getting the other pertinent details and being assured that the young repairman was not injured, Weakley inquired about the stew, which, due to the fall, had now been seasoned with boot leather, mud, and other added ingredients. “Us et it,” the informant replied without reservation.8

Food was at the heart of another story Weakley told about one of the boys on the kitchen staff. This youngster had a particular fondness for desserts, and had concocted a specialty he called “chocolate crony.” The young cook was so proud of his sweet invention that it became an almost daily item on the school menu. When the boy left ABIS, he enlisted in the Army, and Weakley lost contact with him until the day the superintendent visited an Army installation on school business. The commanding officer invited Weakley to lunch at the base, and as they entered the mess hall, Weakley ran into his old kitchen boy. They had exchanged pleasantries and talked about old times for a few moments when Weakley jokingly asked if they were having chocolate crony. A somewhat awkward smile was the only response. Weakley bade him goodbye and took his seat alongside his host. Sure enough, as he opened the menu, his attention was drawn toward the day’s special—“Chocolate Crony.”9

Chefs were not the only professionals turned out by the school. There are accounts of ministers, teachers, attorneys, businessmen, musicians, and scores of craftsmen. Sometimes the process of assisting a student in reaching the pinnacle of his profession required quite a lot of understanding on the part of Weakley. He wrote of Jim, who was mechanically inclined and particularly liked tinkering with old cars. Jim persuaded Weakley to let him try to fix a problem the superintendent was having with his car, and he began the project late one afternoon. When Weakley checked on his progress the next morning, he found the young mechanic had worked all through the night removing the motor from the vehicle and had strewn it across the garage floor. Although somewhat perturbed, Weakley showed his usual patience and inquired about the diagnosis. Jim casually replied that the car “needed new rings and a valve job.” In due time, he had all the parts back in their proper place and Weakley found “the old car ran perfectly.”10

Another success story was a bit more serene. A boy was brought to the school by his uncle because he could not keep him at home. On most occasions, he was found at East Lake Park listening to the organ music of the merry-go-round. His interest in music flourished at ABIS, where he joined the band and became particularly adept at playing the cornet. After graduation, he studied music at a small college and later performed with professional orchestras around the country. One Christmas Eve years later, the Weakleys were in their living room listening to a national radio program when the host made the following announcement: “Next on the program will be a cornet solo, ‘The Holy City,’ by Mr. _____ dedicated to Mr. and Mrs. David Weakley, Birmingham, Alabama.”11

Perhaps the most enduring legacy left by any of the Weakley-era students was that of the very first student, Jimmie _____. It has already been recounted how Jimmie’s quick thinking allowed him the honor of being the first student admitted to the school. There’s no doubt that Jimmie proved a little difficult for C. D. Griffin to manage in the early days of the school. What really needs to be told, however, is how Jimmie’s story ended.

Jimmie “was among those we sent to Auburn in the fall of 1907,” Weakley wrote. “He was handsome, intelligent and possessed a wonderful personality. He was an excellent student, and almost a genius in mathematics. He was an accomplished musician and an excellent printer.

“After completing his studies at college, he enlisted as a musician in the Marine Corps at the time we were building the Panama Canal. Due to his ability, he was soon promoted to director of a regimental Marine Band. He returned to the Alabama Boys’ Industrial School later as instructor in printing and editor of the Boys’ Banner. He resigned at the outbreak of World War I, and rejoined the Marine Corps. In due time, he was promoted to Captain and was killed in the Battle of Belleau Wood. The first boy to enter the Alabama Boys Industrial School was the first to give his life in the defense of his country.”12