1

Redesigning Humans

As we better understand topics such as evolution, genetics, and neuroscience, we start to build and deploy the instruments to alter all life-forms on Earth, including ourselves.

Should we?

What is ethical?

Well, let’s begin by talking about SEX . . .

The Ethics of New Sex

Few topics incite more Sturm und Drang in today’s culture-ethics wars than sex and its consequences. There is not a lot of middle ground left on topics like abortion, stem cells, reproductive options, evolution, LGBTQIA . . . Are you for or against? PICK . . . A . . . SIDE.

Yet, time and again, society’s seemingly iron-clad ethical mores change. In the 1960s sharing a bed without sharing a marriage license was “living in sin” and punishable by law. Now almost three-quarters of women ages 30 to 34 have lived with a partner, and two-thirds of new marriages take place between people who have already lived together over two years.

It now makes People magazine headlines when a couple does not cohabit before marriage.

So while a part of Washington still re-litigates the Bishop Wilberforce versus Darwin debate on evolution, science and our notions of what is sexually acceptable have moved on, fast. Try a thought experiment: imagine you had a time machine. You bring back your four dear old grandparents, and you chat with them about the birds and the bees.

A chat that is just a tad uncomfortable?

With the luxury of having a time machine, they are not the white-haired, venerable icons you remember but randy twenty-something-year-olds. Likely they already knew quite a bit about sex because likely they were already married. But let’s also look at what has radically shifted within reproductive biology. For all time, until the very recent past:

SEX = REPRODUCTION = EVOLUTION

Traditionally, sex lead to reproduction. But now . . .

You can have sex and not have a child.

We decoupled the act from the consequence.

We take reproductive control for granted. We assume we get to choose when to conceive. We have an endless array of choices: vasectomies, IUDs, pills, patches, sponges . . . All carefully, and cheerfully, packaged and marketed. But for all of animal history, for all of human history until the mid-twentieth century, sex and reproduction were tightly coupled. Yes, there was crude birth control, like condoms and rhythm, but sex eventually equaled baby. Women had little control if they wished to have sex on a regular basis. This led to early marriages, prevented a lot of higher education, and derailed careers.

We have decoupled sex and its traditional consequence. We take it for granted, but a couple of generations ago this would have seemed like magic or witchcraft. It is not that grandpa and grandma did not want birth control. Gallup asked about this, for the first time, in 1937, and 61 percent were yay while 23 percent were nay. But governments and religious minorities are especially good at blocking that which they do not approve of. State laws, like those of Connecticut, prohibited “any drug, medicinal article, or instrument for the purpose of preventing conception.”1

As a cheap and effective technology gave women control over when and if to have kids, ethics and laws changed. By 1965, 81 percent of the US population supported birth control. Despite bitter opposition from religious leaders, the Supreme Court issued Griswold v. Connecticut, making it legal to provide birth control information. But it took seven more years for THE SUPREMES to protect access to birth control for the unmarried (Eisenstadt v. Baird). By 2015, 89 percent thought birth control was a good idea, and 75 percent of American women had used the pill or something similar.2

Meanwhile the Catholic Church went the other way . . .

In 1966, 80 percent of the Pontifical Commission on Birth Control recommended allowing . . .3

In Humanae Vitae, Paul VI sided with the conservative minority and prohibited birth control.

Not smart, given that only 8 percent of the US flock agrees.4

Birth control was a key factor in opening educational and career opportunities to women. Between 1962 and 2000, the percentage of women who work increased from 37 to 61 percent, generating an estimated $2 trillion. While the wage gap has yet to close, more women than men are getting college and graduate degrees. Women who work, who are financially independent, have a lot more choices, including who they marry and when, and if they stay. This too shifted bedrock “ethical principles”; according to Gallup, in 1954 a slight majority, 53 percent, “believed” in divorce. By 2017, three-quarters thought divorce “morally acceptable” (including a majority of the “very religious”).5

By 2014, in two of every five marriages, at least one of the new partners had been married before.6

As the sexist Virginia Slims ads once bellowed: “You’ve come a long way, baby!”

This goes to the fundamentals of ethics-morality. When I was in college, my girlfriend and I would joke about becoming a perfectly average family and having exactly 2.4 children. But we never focused on just how weird this statement was. Not the 0.4—the 2, which historically was a tragically low average number. Not enough kids survived; two kids were not enough to work the farm when the United States was 90 percent agricultural, nor enough to provide the equivalent of Social Security in one’s old age. But yet again, as technology changed how and where we work, families no longer needed a half dozen children to tend the farm and animals, to haul water, to gather firewood. Our tech jobs required far more intensive, lengthy, and extensive schooling; better focus on fewer offspring, especially as more survived. Having a large brood became more difficult. Technology changed millennial norms. Global fertility rates dropped from five kids per mother to 2.5 (1950–2016).7

In 1985 the average Iranian woman had 6.2 children, now less than 1.7.8

It does not matter that the mullahs are very unhappy with this trend.

These are astounding changes. Across time, nothing is more fundamental and ingrained into a family structure and culture than kids and grandkids. And yet, once birth control and women’s empowerment took hold, the most fundamental family mores changed blindingly fast. So how do we judge, regulate, legislate, think about the ethics of sex-gender-reproduction for future generations—about what is acceptable and what is not?

One option is to say: Well, those past fools did not know Right from Wrong, but I do . . .

As you continue sipping wine, and getting to know your young grandparents, while casually discussing sex, you really begin to freak them out when you talk about IVF. Imagine how that back-and-forth would go: Well, Gramps, you take an egg and sperm, mix them together in a test tube and conceive a baby . . . Wait, wait, wait just one second, Junior; you are telling me that the two bodies never touch each other and you can now conceive a child? Yep, that’s right, Gramps. Well, I’ll be . . . I learned about that concept a long time ago, in church, and we called it the Immaculate Conception, and it was a miracle . . .

In fifth grade, the United States’s first IVF baby, Elizabeth Carr, corrected her sex-ed teacher and explained: “Not how I was born.”9

Once new technologies become available, they can sometimes allay our fears and alter what we deem to be ethical or unethical very, very quickly. The two “Ps,” the pill and penicillin, freed a generation to experiment with sexuality. Historically justified fears of pregnancy, syphilis, and gonorrhea faded. Suddenly it was acceptable for many of today’s boomers, male and female, to enjoy sex. The average number of lifetime sex partners increased substantially.

Shifts in what is ethically OK can occur with lightning speed. Prior to the first test-tube baby, public opinion was strongly against “un-natural conception.” Yet within a month of Louise Joy Brown’s birth, and all those cute test-tube baby pictures and headlines, 60 percent of the public was in favor and 28 percent opposed.10

Which did not stop James Watson (co-discoverer of DNA molecule structure) from telling Congress, in 1974, that allowing embryo transfers meant: “All hell will break loose, politically and morally, all over the world.”11

Now that you can conceive in vitro . . .

We decoupled conception from physical contact.

Conversation continues . . . As you uncork a second bottle of wine for Gramps, you explain the concept of frozen embryos and surrogate mothers, offhandedly letting your grandparents know that babies conceived today could be born in a year, five years, a decade, fifty years . . . to a different mother.

You can freeze embryos and hire a surrogate mother.

We decoupled sex from time.

Then you share newspaper clippings describing how, to prevent deadly genetic diseases, some kids are now born with a third parent’s DNA; that that addition passes down across generations, birthing children that will have at least five grandparents. Finally, for dessert, you tell them about how women can donate their uterus and help build new lives after they die . . .

Perhaps at this point Gramps might conclude that you smoke too much weed?

Nothing like this was remotely conceivable three generations ago. What we now take for granted would seem like witchcraft to earlier generations. So now let’s talk ethics; had you asked them, way back when, “should this be allowed; is it ethically OK?” . . . They almost certainly would have considered what we are doing today as evil, unnatural, against God’s plan.

Time and again, changes in technology drive massive changes in our daily lives and fundamental societal mores. Science continuously challenges our understanding of sexuality. Technology provides unimaginable options. For instance, in the measure that we begin to map and comprehend what makes a person gay, hetero, or any one of a series of sexual identities, we will understand why “gender” can be such a fluid concept. Some are born 100 percent hetero, and no matter where they are stuck—say, in a prison—they will express zero desire to experiment with the same sex. Others will be, from birth, attracted to their same sex. Period.

Being gay seems to be consistently widespread across cultures and geographies. One might expect that, if being gay were really a choice, then the incidence of homosexuality would be far higher in liberal areas like Scandinavia and far lower in places like Saudi Arabia, where you are murdered if you come out of the closet. But though many more may come out of the closet in one place versus the other, overall incidence, across populations, seems steady. Discriminating against various sexual identities is as idiotic as discriminating against someone who was born left-handed. (Which, by the way, we used to do a lot; the word sinister comes from the Latin word sinister, which means left-handed.)

Being left-handed helps in fights; it is a significant advantage for boxers and fencers. The more violent a society is the more left-handers, because they are more likely to survive confrontations. “Among the Jula (Dioula) people of Burkina Faso, the most peaceful tribe studied, where the murder rate is 1 in 100,000 annually, left-handers make up 3.4% of the population. But in the Yanomami tribe of Venezuela, where more than 5 in 1,000 meet a violent end each year, southpaws account for 22.6%.”12

So far, it does not seem as if genes alone account for homosexuality. A 1994 study by Dean Hammer focusing on gene Xq28 was difficult to replicate. In August 2019, a study of a mere 493,001 genomes showed that there was no one “gay gene,” but there were several parts of the genome that could be indicative of same-sex behaviors; in particular, five loci accounted for 8 to 25 percent of same-sex attraction. Other genetic influences impact “sexual behavior, attraction, identity, and fantasies.” Because these are complex, overlapping traits, “there is no single continuum from opposite sex to same sex-preferences.”13 An identical twin has a 20 to 50 percent chance of also being gay. However, in twins with similar methylation patterns, the chance of both being gay rises to 70 percent.14 So some now posit that genes plus gene expression (through methylation) explain a tendency toward being gay. But, again, it is a tendency, not a direct linear correlation.

It is normal and natural for parts of a population to express a broad range of different sexual desires. In some studies, up to one-third of kids under 25 do not identify with a binary sexual identity.15 Many will, at some point in their lives, under different circumstances, at different ages, at least wonder what it might be like to be with, or observe, two or more people of the same sex.

Some versions of Facebook allow you to self-define across 71 gender options.

Perhaps humans are like Baskin-Robbins, 31+ flavors . . .

And yet there is no third, nonmale, nonfemale, singular pronoun in English.

There is an inclination to reduce sexuality to genetic determinism, many resent and reject this reduction. “Attributing same-sex orientation to genetics could enhance civil rights or reduce stigma. Conversely, there are fears it provides a tool for intervention or ‘cure.’”16 But, if we were someday to learn what defines sexual identity and preference, one can glimpse at future possibilities and ethical complexities, which leads to an extraordinarily divisive question: if homosexuality could be “cured,” or induced for a while, should it be?

Please don’t ask Mike Pence.

Should we develop ways of altering desires safely? Conceivably then your grandkids could choose to live with different identities at different times. While this may sound preposterous, consider the case of a good friend of mine. She lost her ability to make hormones after a brain tumor operation. To survive, she began taking various chemicals that wreaked havoc on her physical and emotional state. Being a serious scientist, she built a spreadsheet and mixed, matched, and adjusted until she found a happy and productive emotional balance. Along the way, she discovered just how profoundly hormonal treatments could alter ones choices and desires. For instance, one combination led her to feel like a teenage boy. As she described it, “All I could think about was violence and SEX.” After a week she thought, “Well, that was interesting,” and moved on to different combinations.

Empathy is a powerful tool. In some schools, teenagers are asked to wear glasses that radically deteriorate their eyesight and braces that make it hard to walk or open things, and they experience sleep deprivation by being awakened at odd hours. After a week of this they become far more sympathetic and mindful of what the elderly suffer. Every day.

What might happen if one could emotionally “walk in the other’s shoes” for a week? A large-scale cohort of gender-transitioning individuals already provides some hints. Alongside operations on their sex organs, many are also opting for gender-affirming hormone therapies (and—wouldn’t you know it?—there is an acronym for this as well: GAHT). These hormonal treatments may alter not only moods but also fundamentals like brain morphology and cognitive patterns.17 Might one eventually become more understanding and appreciative of the opposite sex, of same-sex choices? Or might the general societal tendency be to “cure,” to “make them all normal”?

Other fundamental aspects of sex and reproduction will change as well. How women carry babies may be different; a teen 100 years from now may ask: Did Great-Grandma REALLY carry babies in her body? Wasn’t that incredibly burdensome and uncomfortable?! Sound crazy? In 2017, MDs at Philadelphia’s Children’s Hospital placed eight fetal lambs inside what looked like giant Ziploc bags, filled with amniotic fluid. One survived.18 The images of the lambs growing within transparent bags are a touch disturbing, allowing the UK Register to print one of THE great headlines: “Ewe, Get a Womb!”

But what is scary to us may be normal and natural to future generations who may ask how in the world did babies squeeze out “down there”? “I could never bear that much pain”, and “I don’t think this is even remotely possible given my anatomy.”19

To them, today’s women may seem both heroic and slightly savage?

An external womb technology could be a blessing for all anguished parents of premature babies. Not only would the child have much better odds, but perhaps parents and society could reduce the extraordinary costs associated with preemie survival. A 2005 study estimated US costs of caring for these infants at a minimum of $26 billion.20 A disabled preemie can almost double the parents’ divorce rate and massively impact their employment prospects.21

Within the next few years, we may see the first clinical trials that take premature babies and place them into a plastic sack filled with amniotic fluid, instead of incubators. This might engender one or two ethical quandaries and further inflame one of today’s most contentious debates—abortion. The entire moral underpinning around permitting abortions rests on one premise: “no one should kill a human, but fetuses are not human, yet.” So, unless the mother’s health is seriously threatened, abortions are usually allowed as long as the fetus is unviable. Over the next few decades, these types of external birthing technologies could fundamentally complicate this premise. What external wombs might do is bring forth the viability of embryos by months. And they mostly eliminate the argument that the abortion should take place to protect the mother’s health.

Then we get into far more complex and contentious ethical questions:

- • Rights and desires of the mother versus rights of the fetus?

- • Are there too many people on the planet?

- • Should you bring a child into the world if you cannot, or do not wish to, care for it?

- • Father’s rights and responsibilities?

- • Rape and incest exceptions?

My purpose is not to answer these complex questions for you but to get you, regardless of your current beliefs, to understand that technology can fundamentally alter what we believe is ethical today.

Regardless of which side of the political circus you are on.

Another major ethical challenge arising from external wombs is that once a fetus is outside a mother’s body, it becomes far easier, and more tempting, to intervene. Gradually our kids and grandkids may come to regard cloning, genetic “corrections,” and possibly enhancements, as normal and natural.

In 2001, only 7 percent of Americans thought cloning humans was morally acceptable.

2018? 16 percent.22

Current IVF procedures are mostly focused on passive gene editing; you don’t edit an egg, you simply select embryos that don’t carry the trait you wish to avoid. That is why “Michael” and his wife, “Olivia,” ended up in a clinic trying to avoid having a child whose muscles would contract uncontrollably (dystonia). They were not the only ones, US IVF procedures with single gene testing rose from 1,941 in 2014 to 3,271 in 2016.23

The next step, deliberate gene editing, may soon be coming to a clinic near you. In 2018 a Chinese scientist edited a baby’s DNA, in an attempt to help prevent future diseases (and in a serious lunge for scientific glory). The news unleashed a torrent of condemnation . . . for now.24 But how long will that condemnation last when 59 percent support some genome editing for medical purposes and 33 percent already support human enhancement?25 Those who are most familiar with the technologies involved and their potential are also the most supportive.

Our current ethical logic, reasoning, and concerns could be completely flipped; someday we might ask, What do you mean, you used to carry around a baby with you when you went mountain biking, or when you travelled across the world and were exposed to diseases? Why wouldn’t you just leave the child inside a nice, protected, safe environment? How could you have been so irresponsible? Then the follow-up might be: and what do you mean, you did not edit out the genes you know to be harmful? Don’t you realize your kids could sue you for not removing HER-2 or p53 if they get cancer?

We don’t have these options today; we are not able to alter safely and predictably. But we will. And when we do, future folks might not be kind in their judgment of “barbarous choices” or “primitive birthing conditions” of their ancestors.

And then there is also the small matter of needing a partner to reproduce . . . As marriage moves far, far beyond the traditional one-man–one-woman-for life paradigm, there are increasingly more variants and experiments. Many of these take place within the LGBTQIA communities, 37 percent of whose members have chosen to have kids. The more than six million resulting children come from every type of relationship, ranging from adoption and anonymous donors through using the sperm of a brother or friend. Question is, given the opportunity, would same-sex relationships prefer to have kids with only their genetic material? Enter IVG, in-vitro gametogenesis . . . In May 2003, a University of Pennsylvania team fundamentally changed the rules of reproduction. Using the velvet rope of highly technical language, they reported: “Mouse embryonic stem cells in culture can develop into oogonia that enter meiosis, recruit adjacent cells to form follicle-like structures, and later develop into blastocysts.”26 In civilian terms: you can take a cell and reprogram it to clone mouse body parts or perhaps even whole mice.

Fast-forward a short decade later: in 2012 a team at Mass General generated human eggs from human ovary stem cells. Now serious folks are asking, What does this eventually mean—that single individuals may conceive a child? Or two same-sex partners can mix and match their genetics of their baby? Or even “multiplex” various partners?27 Add an external womb and gay men could conceive and birth a baby without a female mother . . . something many of us would consider weird and unnatural today but may seem to be a normal and natural choice in a couple of generations.28

Changes in longevity will also impact sexual mores. As women live far longer and grow more comfortable with themselves, some are rebelling against the idea that “a man’s validity, as a man, depends on his significant other’s total and utter commitment to him of her body.”29 Close to one-fifth of the population has participated in consensual nonmonogamy (CNM) at some point. And 5 percent is actively practicing CNM at any given time.30 More often than not, it is women who are suggesting this arrangement. Polyamory, something that tended to be the privilege of powerful men, is spreading to both sexes. Some see it as a more ethical and rational system than the current notion: take exclusive, lifetime possession of your partner’s body.

And why stop with merely human sex? Machines will also likely enter the intimacy debate. The October 3, 2018, Houston City Council debate was a touch unusual. Amid the usual bureaucratic droning about city bureaucracy there was an impassioned zoning debate. This was unusual in a city that prides itself on mostly laissez-faire zoning. What led to this Sturm und Drang? A robot brothel . . .

In an attempt to provide “try before you buy,” KinkySdollS, a Canadian sex robot company (Canadian! who knew?), began building a comfortable facility so folks could try out their $3,000 creations. Pastor Vega was displeased about having a robot brothel in his neighborhood. So he gathered over 10,000 signatures from outraged locals, arguing: “A business like this would destroy homes, families, finances of our neighbors and cause major community uproars in the city.” One council member added that “he planned to record the business’ patrons entering the building and shame them online.”31

Machines will accentuate the tension around the ethics of sex wherein the only objective is pleasure. Some will argue that sex, love, and intimacy can be decoupled, and ever-improving robots will provide disease-free, toe-curling orgasms. Furthermore, one cannot, so far, hurt or abuse a robot. Norms and acceptance of these kinds of ideas vary across societies and circumstances. When 432 Finns were asked if robot sex = cheating, when “you cannot tell a robot from a human,” single people got somewhat of a pass—but married folks, not so much. In most cases having sex with a robot was seen as less egregious than having sex with a prostitute but more serious than masturbating.32 It will be interesting to see how these mores evolve. Many will retort that true sex requires love and that removing intimacy from sex dehumanizes us.

Others may just blend the two and marry a robot.

As has already occurred in China and Japan.

So in judging future sexual technologies and norms and establishing what is RIGHT and what is WRONG . . . Perhaps you, of all people, are far more ethical, aware, AWAKE. You know the ethical thing to do. But just for yuks . . . Try the same thought experiment we started this chapter with on yourself: You and your partner are brought to the future by your spry hundred-year-old grandkids . . . do you think they will say “Oh, there is really nothing new to talk about—sex, mating, and childbirth are just the same as they were when you lived a century ago”? Do you really think sex-evolution is going to look just like it does today?

Fat chance.

So how do we decide whether and how to upgrade humans?

Radically Redesigning Humans

Of course, the first and obvious question is, WHY? Would people really want to change their bodies? What possible evidence do you have?

Of course, you mean besides the 17.7 million plastic surgery procedures performed in the United States alone?33

Apparently, not all of which were done for medical reasons.

Then again, one thing is getting a tummy tuck, Botox injection, a nose job, and quite another is a true redesign. We are still far, far away from having a complete map of our operating system. We still don’t know what most genes do or what other genes they interact with. Many genes can have multiple functions, and there are huge stretches of the genome that we ignorantly thought were “noncoding.” Furthermore, it is not just our genes that matter, so too do the viruses and bacteria we interact with (virome and microbiome), our past traumas (epigenome), our environment (metagenomics), and a host of other factors.

Any attempt to alter humans is like playing a Star Trek multidimensional chess game. Move a piece on one plane and it can have cascading effects on many other levels. Really complicated. But we are learning how to move specific pieces on each of these levels, and some of these moves could fundamentally alter the organism. As one begins to understand the fundamental instructions and expressions of the human genome, one can begin to grow, and alter, specific body parts.

Would it be ethical to radically remake future generations?

One reason we may wish to redesign is that we are singularly un-diverse. The differences between us eight billion humans are miniscule for one simple reason: not that long ago, humans were almost selected out. Of the thirty some-odd versions of our close ancestors, only one species survived. Us. And we did so by the skin of our teeth. Perhaps we all descend from one surviving African mother. She was not the only woman—far from that—but she is the only one whose children had children that had children . . . Family lines die out; hers (mostly fortunately) did not. Further along, those of us with European ancestry descend from less than a dozen clans. No matter how much racists, and some “leaders,” try to convince us otherwise, we are one humanity. And therein lies the problem . . . We are basically a monoculture and thus vulnerable to extreme plagues and extinctions.

Having a single species, one of this size and geographical spread, is REALLY unusual. Chimp and bonobo populations are far smaller than those of humans, yet their genetic diversity is far greater.34 And wouldn’t it be odd if there were just one species of whale, bear, and feline?

For much of hominid history we coexisted, likely quite violently, alongside other close species.35 We interbred with Neanderthals. We interbred with Denisovans. We interbred with other species of humanoids. As one evolutionary biologist put it: “We’re looking at a Lord of the Rings–type world—that there were many hominid populations.”36

Go to any natural history museum, and you will see our common ancestors came in all kinds of shapes and sizes. But all have one thing in common. We were all naturally selected for this Earth and its various environments. If we ever wanted to live anywhere else . . . Well we never evolved, or adapted, to bear the heat of Venus, the barren wasteland of Mars, the liquid methane seas of Uranus, or the brutal vacuum of space. This leads to two issues. Even within a capsule, space tourism is really hazardous to your health. And, once you get there, it may not be the paradise you dreamt of.

Start with the voyage. Changes in gravity distort hearts, making them more spherical, and wreaks havoc on eyes; 60 percent of those who inhabited the International Space Station suffered significant loss of vision. High-energy particles, constantly crashing through your skull, reduce cognition. And the constant noise, elevated CO2, and cranial pressure lead to deafness. A trip to the closest colonizable, planet, Mars, is a huge issue; the trip radiation is the equivalent of getting a full CT scan every five days.37 In practical terms, that means women astronauts can’t go to Mars today; they are government workers and as such are limited in their overall radiation exposure. Men, who on average have less fat and absorb less radiation, can just barely make it. But, in space, their bones demineralize faster than women’s, so they would arrive more weak-kneed and prone to kidney stones.

But other than that . . .

Even armored and encased, our bodies are vulnerable to environments that they have not evolved for. Attempting anything further than Mars, using today’s technologies, would lead to rapid death. No planet in this solar system is “homey.” Even if we found an Earthlike planet: a similar atmosphere, with relatively minor variants in oxygen or CO2, would likely kill us after a while. The same is true of relative radiation, circadian rhythms, abundance of some really unfamiliar plants, animals, and diseases.

Maybe we want to splice humans with Deinococcus radiodurans genes; these creatures thrive inside nuclear reactors.

Distances beyond our relatively small solar system are almost incomprehensively vast to creatures with our life spans. Current methods would get us to the nearest planet outside our solar system, Proxima Centauri b, in a mere 54,400 years.38

Dada, are we there yet, are we there yet, are we there yet?

The bottom line is, to ever get anywhere in our galaxy, we aren’t talking about small modifications but a wholesale redesign of humans. Nothing has prepared us, evolutionarily, for radically different environments. Nor will we have time to naturally and gradually evolve, nor would we tolerate the enormous costs of looking for one surviving human among millions of mutants.

So why bother, why even think about going to such extremes? Actually a single picture tells you all you need to know . . . Voyager 1 took the ultimate Valentine’s Day selfie, when it turned around, in 1990, and photographed Earth from a mere six billion kilometers away.39 If one looks really carefully, in the midst of a series of colored bands, is a teeny, tiny speck of white.40

In astronomical terms this selfie was not even very far away.

Voyager had to travel three times as far just to reach interstellar space.

That is Earth. All of it. Every plant, animal, human, civilization—ever—lives, or lived, on that tiny speck. And, yes, we have been most creative in finding ways to eliminate most life on that tiny dot: climate change, acidification, methane blooms, nukes, biowarfare . . .

One cartoon describes aliens observing Earth:

“People on this rock fight over Gods.”

But in the context of this selfie of all humans, ever, it is not just our peers we must worry about. Space is a tough neighborhood. Those pretty nebulae you see are stars blowing up and taking down whole solar systems. Black holes, galactic collisions, pulsars, supernovae, massive solar flares . . . There is a wide variety of things that vaporize planets (and all life on them).

So if one wishes for humans, and their descendants, to survive for a long time, it makes a whole lot of sense to get off this planet and on to many more. That implies that, over the next centuries and millennia, we have to radically redesign our bodies.

Were one to put together a shopping list of “here is what I might need to go to space”: Begin with our bodies; they are, to say the least, inefficient in space. We do not need long appendages and core strength in zero gravity. The bulk of our body is used to propel and protect us on a planet with predators and significant gravity. One consequence is we consume a lot of calories. One could see a completely redesigned, far more compact body.

Would we really lose anything with smaller bodies?

Recall the joke poster showing a brain with the caption:

“This is the real you. The rest is just parts and casing.”

So the one part we would wish to seriously expand as we travel is our brain. Because we are at the limit of what the birth canal can do; women, and maybe men, would need to always birth through caesarean sections, or conceive and develop in external wombs. External wombs could also better shield the embryo against radiation.

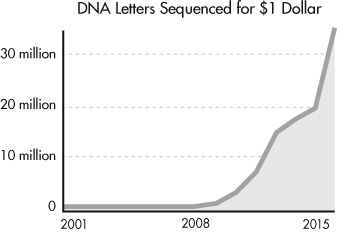

What would be the first steps in an initial redesign? Start with the basic code, genes. Unlike treatments by MDs, stays in hospitals, or pharmaceuticals, gene sequencing and design is getting faster, better, cheaper. The cost of sequencing DNA base pairs fell 175,000-fold between 2000 and 2015.41 In turn, the number of base pairs sequenced, the basic gene code, exploded.

All of this accumulated data provides enormous libraries that give us blueprints to attempt to build various life-apps. One way to visualize this: Think of a single grape as an app, similar to apps on your phone. But instead of editing and uploading pictures to Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook, life code builds life-forms. How does this work? A grape falls off the vine and, on the ground, seeds begin to execute the instructions written in the DNA . . . build a root . . . build a stem . . . build leaves . . . grow faster . . . flower . . . fill the branches with grapes . . . repeat.

And by the end of a few summers, you are sitting under a wonderful trellis, grapes overhead, drinking fine wine.

Once you have the genome, the full life code of a grape, you can compare it to the genomes of other grapes, or other life-forms. This tells you how minute changes turn a green grape into a large purple grape, one variety into another, one species into another. Even minute variations lead to really different outcomes.

Ponder this while drinking cabernet, merlot, pinot noir, sauvignon blanc, zinfandel, tempranillo, nebbiolo, moscato, and so on . . . All this tasting is strictly in the interest of scientific research, of course.

Now apply this to humans, even though we are far less genetically diverse than grapes. As we understand how other animals function, we too may be able to understand their gene function well enough to induce functions that would be truly useful across space, like hibernation; one scientist describes this process as just leaving the pilot light on. It is not deep sleep; in fact some animals come out of hibernation sleep-deprived.

Hibernation can occur in warm and cold weather, or during extremes of drought.42 In Ken Storey’s Carlton University lab, one might run across red devil squid, giant tuna, ground squirrels, wood frogs, and lemurs.You can place some of them in freezing cold, with little oxygen, and desiccate their bodies, in Storey’s words: “They turn off their nuclei and all of their genes. You can’t do that without dying. Then they turn off all the processes in all of their cells. You can’t do that either. If you drew a graph of it, it would look like they were alive, and that they died, and then they came back to life. Anything that has a time constant of ‘dead’ in the middle of their graph but that is not actually dead, that’s what we study.”43 Some vertebrates can spend months with “up to ~65% of their total body water frozen as extracellular ice and no physiological vital signs, and yet after thawing they return to normal life within a few hours.”44

There is some anecdotal evidence of potential capacity to cold-hibernate for short periods in humans. When a Norwegian doctor, Anna Bågenholm, went skiing in a remote area of northern Norway, she tripped, and fell down a cliff, into a pond, where she was trapped beneath eight inches of ice. Two hours after her heart stopped, she was finally helicoptered to a hospital. Her core temperature was 13.7°C. Anywhere else she would have been declared DOA. Fortunately this was Norway where the saying in the emergency room is “you are not dead until you are warm and dead.” It took months, but eventually she made a full recovery.

Various ER docs took note of dozens of cases like Anna’s and began clinical trials on an innocently named procedure, “emergency preservation and resuscitation (EPR).” Basically if someone is rapidly bleeding out, the idea is that a surgeon could pump the aorta full of really cold saline, to bring body temperature below 10°C as fast as possible, which would provide an hour to repair bullet or knife cuts, and then gradually rewarm patients.45

NASA is now looking at whether astronauts on a six to nine month journey to Mars could enter a controlled hypothermia that would lower their metabolic rate 50 to 70 percent.46 While this sounds far-fetched, there are studies of two Tibetan monks being able to willfully increase or decrease their metabolism by 61 percent and 64 percent, respectively.47

Weirdest of all, there do not seem to be specific or unique genes associated with hibernation, just differential gene expression.48 Our bodies may already have the necessary conserved code to hibernate, but we gave up this trait long ago. So, in theory, humans could achieve these states without having to modify their fundamental gene code, just their gene expression.

But even these kinds of significant engineering feats are tweaks, not fundamental redesigns of a human body. So it is worth asking: as we are able to understand and modify life, and even ourselves, where are the ethical parameters of a radical redesign?

We keep discovering that life on earth can thrive in weird places. Since Alvin’s February 15–17, 1977, dive to the bottom of the ocean, we know life can thrive without sun, under extreme conditions, as long as it is near hot vents. Lunch for some of these life-forms is hydrogen sulfide and ammonia in concentrations that would quickly kill us. (This find was so surprising that there was no specialized biologist on board and no way to preserve the unexpected specimens, other than Russian vodka smuggled on board in Panama).49

Under extreme conditions, life often finds a way. Over the past decades we discovered that the range occupied by extremophiles gets broader and broader. There seems to be almost no space too hot, too cold, alkaline, or acidic where life on Earth does not thrive. Picrophilus torridus swims in sulfuric acid. Halophiles love lakes with 20 percent salinity. Methanopyrus kandleri thrives in a balmy 122°C.

As we find more and more of the enabling gene codes we may, someday, be able to engineer bacteria and perhaps even plants or animals that can grow in environments quite different from those of Earth. If you drive a mere eight hours north of Toronto, the end of the road is the Kidd Creek Mine. Get in a basket, go down two kilometers and sample some of the oldest known uncontaminated water on the planet, perhaps isolated from any contact or mixture with the Earth’s surface for a billion of years. Within, there is evidence of a thriving microbial community around the Earth’s crust, one that metabolizes sulfates and other chemicals.50 The same may be true under the surface of other planets and moons in our solar system. Even the moon may be inhabited by bacteria left behind in bags of astronaut poo (yuck!). So life out there could be far more common than we currently believe; privately, about nine out of ten top astrophysicists think there is life on other planets and that we will likely see signals during your grandkids’ lifetime.51

NASA is actively looking for “life as we don’t know it.” Some forms of life may be radically different from those on earth, which is why they aren’t just looking for oxygen but for chemical imbalances in general within the atmospheres of distant planets.52

Until recently, all life as we knew it was based on a single molecule, DNA. The four letters representing the chemicals that make up the backbone of life, ATCG, are enough to produce everything from bacteria, oranges, and mosquitoes through snails, politicians, and puppy dogs’ tails. But as we eventually modify life-forms, and even ourselves, to adapt to other planets, heredity may not be based on today’s basic gene code. In small lab enclaves in La Jolla, California, and Alachua, Florida, something else stirs . . .

Life is now being modified to create heredity with alternate base pairs. Instead of just ATCG, we can now write life with ATXY, or ATCGXY. Not only can this produce novel proteins, but it could, in theory, rewrite a branch of life and create creatures that would not mate or interact with anything on Earth. Or, in some cases, it could interact with some of today’s creatures, creating an enormously expanded biological tool kit.53 One could conceive of plants and animals on Earth immune to most viruses and bacteria. And this has one other modest implication . . .

Because you can build non-DNA life,

life and heredity can occur using various chemicals.

We are not a unique solution.

Humans could, eventually, seriously speciate. In altering our basic gene code and physiology, we could return hominids to a state where several variants live side by side on Earth. Remember, this was the natural order for a longer period of time than that in which we, and only we, have ruled alone.

As the cost of altering bodies drops, as it gets safer, and as the need arises, if space travel and colonization were to really kick in, there will be more and more pressure to upgrade our basic biology to adapt to very different conditions. While this seems inconceivable today, and wildly unethical, it may seem unremarkable to our descendants.

The ethical norms we set today on how to treat those who look different from us, and how we treat our closest ape relatives could set the tone for future peaceful coexistence or for ruthless dominance by another hominid. Which brings up a final question: If we can seed or modify life on other planets so as to help us create an atmosphere, make food, build fuel reserves, and seed new civilizations, should we? The answer may seem obvious to our space-exploring descendants. But whatever answer you give today you can be sure tomorrow’s discoveries, concerns, and challenges will upend today’s accepted ethical response. Because, after all, ethics change.

Renovating Our Brains?

Planaria, a.k.a. flatworms, are strange creatures. Cut one in half. The side with a head will regenerate the rest of the body. Weirder still, the back half will also regenerate a head. You can breed a gaggle of planaria by cutting them up.

This led one scientist to declare these animals “immortal under the edge of a knife.”54

Somehow a partial flatworm body knows which body parts it is missing and simply regrows them. Even stranger, as a new head regenerates, out of the former back of a planarian, the new brain remembers what was in the old head. Memories transfer animal to regenerated animal, even though the new animal part started out with no brain and had to grow a new one.55

It gets even weirder: one day Tufts’s Michael Levin began playing with electricity to see how this might disrupt planaria’s normal regenerative growth patterns. Suddenly he had four eyes and two heads staring back at him.56

Electricity can direct bodies to grow extra body parts, including heads.

Brains turn out to be strange things, memories even more so. Levin describes caterpillars as soft-bodied robots that crawl and chew plants. Then they go into cocoons and metamorphose. During this process they liquefy their nervous systems and brains, emerging as something quite different; now they are flying robots that seek nectar. But here is the really odd part: the butterfly remembers some of what the caterpillar learned.57

While flatworms and caterpillar brains may be useful role models for studying certain politicians, they are certainly not human brains. To understand how human brains operate and how to cure certain diseases, you eventually need to experiment on human brains. But, oddly enough, there turn out to be few healthy volunteers for extreme interventions—go figure. So the failure rate for central nervous system drugs continues to be astoundingly high.

Enter another strange emerging science discovery: organoids. The tale begins in 2006 when a smart Japanese scientist, Shinya Yamanaka, figured out that mixing four chemicals together with human skin cells could produce undifferentiated stem cells. These are the most basic cells in your body, the ones created after you begin as a single conceived cell, from the fusion of sperm and egg. That cell divides and becomes 2 . . . 4 . . . 8 . . . 16 until, ten trillion cells later—voilà!—it is you. For the first few divisions, all of these cells can become any part of your body (totipotent). Think of this as a skier at the top of a mountain: there, and only there, you can take any path, but as soon as you commit to one slope, you get fewer options. Yamanaka built a ski lift for all of our cells so as to restore their pluripotent qualities.58 Skin cells could now be reprogrammed to grow into different parts of your body.59

Then came Margaret Lancaster, Jürgen Knoblich, and a great team that discovered how to take stem cells and grow minibrains in a dish.60 No big deal, right? As different groups became better at growing organoids and keeping them alive, some odd things began to occur. These tiny organoids, a millionfold smaller than a human brain, began to self-organize into differentiated brain tissues. Over the course of ten months, scientists began to see random neuronal firing begin to self-organize into brain waves.61 (One of the fundamental measures of brain activity occurs when neurons start to fire together. In humans this activity is associated with many functions, including memories and dreaming).

Soon thereafter Alysson Muotri created automated brain organoid farms; afterward, Lancaster, Knoblich and their team began systemically evolving neural networks. Once you can grow robust organoids, you can begin to play Mr. Potato Head and plug in various other inputs-body parts. By developing, retinal cells within brain organoids these minibrains develop photosensitivity.62 This may recapitulate how early creatures developed the most primitive of eyes, and it is a big step toward learning just what conditions will generate different functional brain cells. Other groups are taking human brain organoids and placing them in mouse brains . . . to see what develops.63 Brain organoids are even going extraterrestrial; NASA launched them into space to see how minibrains develop in zero gravity.64 (Preliminary report? They come back larger and spherical, not like blobby cells. A baby born in space might develop an anatomically different brain.)

As organoid research scales up, one ethics review, under the subtle subheading “issues to consider,” came up with a slightly worrisome scenario: “As brain surrogates become larger and more sophisticated, the possibility of them having capabilities akin to human sentience might become less remote. Such capacities could include being able to feel (to some degree) pleasure, pain or distress; being able to store and retrieve memories; or perhaps even having some perception of agency or awareness of self.”65 (Watch out for Neo, as you queue up creepy theme music from The Matrix.)

Altering the brain is changing humanity. Is there really any willingness to alter our brains? Well . . . many are not waiting for radically different brain designs and implants to modify neuronal function; millions already use DOSE neurochemicals (dopamine, oxytocin, serotonin, and endorphins). Prescription antidepressants such as Prozac, Celexa, Effexor, Paxil, Zoloft, and many others grew fourfold within a decade, so, by 2008 one in ten Americans had attempted to alter their emotional states.66

(And neither the financial crisis, nor Trump’s presidency, nor COVID had occurred yet!)

Brain and pain modulation is quite risky. In the United States about a quarter of those prescribed pain medication misuse the products. One in ten users become addicted.67 Every day about 130 people die from opioid overdoses. And speaking of ethics, or the lack thereof: between 2006 and 2012, various companies shipped 76 billion oxycodone and hydrocodone pills. The poorest were the most lucrative target; “West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee and Nevada all received more than 50 pills for every man, woman and child each year. Several areas in the Appalachian region were shipped an average of well over 100 pills per person per year.”68 Mingo County, West Virginia, got 203 pills per person per year. These numbers are so staggering that they reduced the nation’s average life span by four months.69 Given that at least two-thirds of the deaths from overdoses are coming from prescription medications, one might ask, are we incarcerating the right people?70

There is plenty of justified pushback on altering fundamental brain functions. The Presidential Commission on Bioethics had a few cognitive naysayers. Their objections typically landed them in a few tribes:

- • Proto-Calvinists: Achieving success with the help of a pill is akin to cheating or taking the easy way out. Success is supposed to be the result of personal efforts and hard work.

- • Karmaists: Happiness and well-being are supposed to be rewards for virtue and good character, not an outcome of medication.

- • Self-flagellators: Even when memories are life-changing traumas you must come to terms with good and bad experiences. No “fraudulent happiness” for you.

- • Hystorioids: If we people cannot remember the bad and traumatic they may not be able to avoid it in the future.71

Nevertheless, we are unlikely to quit attempting to quell, stimulate, enhance our emotions and thoughts. The rewards for being able to modulate brain activity safely are so lucrative and, sometimes, so urgent that, despite massive failures, many university, pharmaceutical, and brain labs are still investing billions.

Drugs are not the only way to alter brain function. About three million epileptics do not respond to drugs, so various labs are experimenting with implantable brain stimulators. These types of devices, internal and external, are also being deployed to treat extreme depression and chronic pain. Eventually one might see reality modulators used to eliminate rage, impulsivity, depression, and aggression.72

As we get better at mapping the brain, intervening in its function, we will face multiple ethical questions as to what is acceptable, for what purpose, at what stage in life. Who should prescribe such drugs or treatments? How broadly? Should schoolmasters have any say in their use? How about judges, police, and prison guards? Military? National governments? Should how we feel, what we experience, be our choice?

It is safe to say that we will continuously challenge the boundaries of what we consider ethical and acceptable today. The ethics of altering, growing, and developing brains is still in infancy. There are still disagreements as to what consciousness even is, where it resides, how to measure it.73 It is one more area where what we believe acceptable and normal today may be radically different tomorrow. But as we face these vexing challenges, we must remember why we are even able to ponder these issues. By far the most powerful technology we possess is the human brain itself. What the human brain conceived of and designed already furthered the evolution of humans and altered the whole planet. In discovering and spreading the use of fire, we were able to cook and absorb more calories and fats, which in turn augmented the brain’s development. As we learned more, we modified our societies and in turn modified our brains and emotions, selectively weeding out some forms of violence, developing advanced social systems, and evolving our ethics. Altering our brain is indeed changing our humanity.

(But perhaps some, or many, of you are convinced, absolutely certain, that we should never alter the human brain. In which case, I’d love to hear your thoughts, after reading the next section, as to how should we judge and treat the criminally insane.)

Pathologically Sick . . . and Imprisoned

When you see a video of someone surfing an 80-foot wave, a mountain biker charging along a sharp ridgeline, a brutal tackle, someone climbing El Capitan without any ropes or protection, two words suffice: “That’s insane.” Unfortunately, the same two words pertain to the worst perversions and the most heinous of crimes. What if those two words actually turn out to be true vis-à-vis many criminals?

Edward Rulloff was unusually accomplished: a doctor, lawyer, botanist, schoolmaster, photographer, inventor, scholar of Greek and Latin, carpet designer, phrenologist, and philologist.

He also happened to be an arsonist, embezzler, burglar, con man, and serial killer. Rulloff started his spectacular criminal exploits quite young; soon after he began his first job, the store he worked in burned to the ground. The poor owner rebuilt, kept Rulloff, and promptly suffered the same fate. During his next job, law clerk, Rulloff stole a bolt of expensive cloth and ended up in jail. After his release, he beat and tried to poison his new wife. Then he murdered his sister-in-law and her small child. And not long after, he murdered his own wife and child. After a death penalty conviction, and a decade in jail, he escaped, ended up teaching at a college, and continued burgling on the side. When the law finally caught him, again, he applied his legal skills and got released on technicalities. After another few years he was found guilty of yet another murder and publicly hanged. His degree of evil was so extreme that doctors dissected his brain, searching for clues leading to such extreme behaviors.74 Rulloff’s brain turned out to be 30 percent larger than the average brain, the second largest on record at the time.

Wander up to Cornell to see Rulloff’s preserved brain.

We are still far from understanding what it is about sociopaths’ brains that make them so very toxic to civilized society. That does not stop lawyers from presenting colorful scans of brain activity in an attempt to explain their client’s criminal behavior; in two out of every five capital murder cases “neuroscience” is trotted out in attempts to lessen responsibility. (“He is a sick boy, your honor . . .”) Maybe so, but we just don’t know yet, despite CAT, EEG, MRI, and PET scans.75 Eventually we may acquire a better understanding of core judicial concepts like “state of mind,” “degree of pain and suffering,” “ability to distinguish right and wrong,” and a host of other conditions that are judged every day in court but that are hardly standardized and measured.

But fast-forward a few decades and assume neuroscience progresses to the point where it can statistically, or even individually, tell you that a particular act was likely the result of mental illness. Perhaps someday neuroscience could approach the accuracy of fingerprints and DNA as evidence. If so, that would create incredibly complex ethical challenges.

What if many of those who transgress really are sick . . . and we can prove it?

What if basic brain circuitry-function induces a significant percentage of serious crimes?76 There is some evidence that psychopaths, and other mentally ill folk, really are different. Statistically prisoners are likelier to be mentally ill and suffer from traumatic brain injuries.77 And they may have real problems processing outcomes and consequences; Harvard’s Joshua Buckholtz scanned the brains of prisoners asked to choose between a little money now or more later. The resulting patterns were quite different from “normal.”78

Yes, one big reason for the standard deviation in these experiments is that we systematically commingle criminals with the mentally ill. This was a common practice through the mid-nineteenth century. Then came the daughter of two depressed parents, Dorothea Lynde Dix, an extraordinary woman who opened her first girls’ school when she was fifteen, educating both the well-off and the poor together. She then worked as a nurse, witnessing the horrors of the Civil War up close. She later realized, while visiting jails, just how important it was to deal with, and avoid criminalizing, the mentally ill. A relentless lobbyist, she got state after state to reform, to focus on improving the lot of the sick. And, for a while, it worked.79

Not all who walk past plot 4731 on Spruce Avenue in Cambridge’s Mount Auburn Cemetery pay attention to the modest tombstone. Fewer still realize how instrumental Dix was in getting the mentally ill out of jails.

But we all saw the movie One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest and know that the old insane asylums were neglected and ended up plagued with overcrowding, sexual abuse, violence, and Nurse Ratcheds. So a coalition, led by well-meaning liberals and state-budget hawks, dismantled the asylum network, undoing Dix’s work.

In 1955 there were 340 psychiatric beds per 100,000 US citizens. By 2005 there were 17. Some of the released were cared for at home, some got fancy new psychiatric drugs. But many ended up in a prison. Of the seriously mentally ill, two in five have served time. Many of the remaining are homeless. In states like Arizona and Nevada, there are ten times as many sick folks in jail as there are in psychiatric hospitals. In a sense we are right back in the middle of the nineteenth century, when Dix began her reform movement to take the mentally ill out of jails and provide more humane treatment.80

Criminalizing mental illness blurs the lines of justice. Within the LA County jail 90 percent of the mentally handicapped become what the guards call “frequent flyers”; 31 percent have been in jail ten or more times. The cost is especially high for women, who, in general, are less violent than men . . . unless they are mentally ill. At least one in of three women in jail is mentally ill. Others feel this estimate significantly undercounts and that the real number is 75 percent.81

Who to incarcerate and for what gets really complicated when one person commits a crime and a second person commits a similarly heinous crime, but only the first is fully cognizant of his actions. An estimated 1 percent of the US population are psychopaths, but male psychopaths are about one-quarter of the prison population.82 On average, these convicts, who lack empathy or remorse, are guilty of four violent crimes before they turn forty. They process words like hate and love in different parts of the brain than most of us do. (Only in the linguistic part, not the emotional part.)83 Those who are not convicted, who can hide their condition better, tend to congregate in law enforcement, military, politics, and medicine. Some of the extremely sick can deceive masterfully; one University of Washington psychology professor described one student of his as “exceedingly bright, personable, highly motivated, and conscientious.” Then his employer, the Republican governor, thought the same. His fellow volunteers at Seattle’s suicide hotline loved him. All thoroughly fooled by mass murderer and rapist Ted Bundy.84

I am not arguing that biology drives, or is behind, all evil acts. Study after study reiterates that a child’s upbringing matters; if context does not matter, then Mexico would not have seen a tenfold increase in cartel-related murders in eleven years. Nor would we see the agents of Stalin, Mao, Hitler, and Pol Pot suddenly march in lockstep to kill millions, including babies. But there are some particularly evil individual outliers in every society, folks whose head is just not right for a modern, more civilized society.

In evolutionary terms, one could see why partisans who could fool the enemy and then perform a complete herem—the annihilation of the enemy all wives, all children, all animals, in the name of God—might be useful to defend the tribe, the belief system. But as societies became less violent and sadistic, past behaviors, acceptable in a Game of Thrones, are now taboo. And those who practice them are justifiably labeled sick, genocidal maniacs.

But if it does turn out that homicidal maniacs are really sick . . .

First question: Why and how should we punish these sick individuals?

- • In proportion to the harm caused? (Even if they did not fully understand they were doing serious harm?)

- • To protect society going forward? (Should sentences for the mentally ill be longer?)

- • To rehabilitate? (What if there is no reliable cure-hope of rehabilitation, if these brains are too broken and too dangerous?)

- • To stop them from enjoying others’ pain? According to University of Chicago’s Jean Decety, the worst get aroused by suffering.

Second question: As we get better at predicting behavior, do we act preemptively?

- • Might we someday be able to predict inhibition and aggression based on damage to the anterior cingulate cortex?85 Or maybe the ventromedial prefrontal cortex? Or maybe a faulty amygdala?86 What if fMRIs could identify many psychopaths?87 Innocent until proven guilty, or do we enter the realm of Minority Report?

- • What if we could detect lies based on blood-flow patterns?88

- • Should we treat criminal and potentially criminal behaviors? How aggressively? (In 2019 Alabama became the seventh state to chemically castrate some sex offenders.)89

Third question: If we could fix a psychopath’s brain wiring, do we enforce the change?

All of these questions, and variants thereof, have been pondered time and again by prison wardens, lawyers, academics, philosophers, and Hollywood. But a lot of the debate is abstract because we have yet to find a faster, better, cheaper solution to stop violent crimes by the mentally ill. So we continue to fill prisons with the very sick—even though almost everyone would agree that this is fundamentally wrong. Yet, somehow, we seem to find endless money for new maximum security but no money for humane asylums.

Advances in pharmacology and brain research might someday alter the equation, forcing us to face some complex ethical conundrums. The more people look, the more chemical compounds they find that can alter moral judgments. For instance, a strong psychedelic like Psilocybin or the “love drug,” Ecstasy (MDMA), make some people more generous and tolerant.90 A box of Citalopram (Celexa) carries the usual list of potential side effects, including problems with sleep, sex, and metabolism. And then Oxford’s Molly Crockett discovered one more side effect: Celexa may change your ethics; apparently it increases empathy and reduces willingness to harm others. (In a follow up study, folks taking Celexa were willing to pay twice as much to prevent a stranger from getting an electric shock.)91 Another drug, Levodopa can make you more altruistic. Whether it be these or other compounds, we are getting better at mapping brain circuitry and inducing or short-circuiting specific emotions.

Don’t like the idea of taking drugs? Eventually, could we, should we, reduce aggression using technologies like deep brain stimulation?92 Leiden University’s Roberta Sellaro showed how mild stimulation reduces your stereotyping of “others.”93 So, one day, when better alternatives are available and broadly accepted, future generations may look back on us and ask: What was wrong with these people? How dare they have treated the mentally ill with such appalling and deliberate cruelty! They used to jail, and even execute, folks who were just sick!