Afterword

Of all these volumes of the Collected Short Stories series this one is my favorite. Tales that for years have cried out to be presented together have now found a home in the same binding. An era in the life of Louis L’Amour is finally available in a manner where the work almost becomes an autobiography in fiction.

The first several stories in this collection are some of the most recently written, stories that Louis wrote from the early 1950s to the early 1960s; they show the end of an arc that also included “The Moon of the Trees Broken by Snow,” a story published in The Collected Short Stories, Volume One. The rest of this collection, however, flashes back to Louis’s very beginnings as a writer and, in fact, includes the first story he ever published: one recently unearthed and offered here for the first time.

“Death, Westbound” was actually mentioned by Louis in his memoir, Education of a Wandering Man, although he didn’t mention the title. “I placed my first story for publication,” he wrote. “It was a hobo story, submitted to a magazine that had published many famous names when they were starting out. The magazine paid on publication, but that never happened. The magazine folded after accepting my story and that was the end of it.”

Interesting, but not exactly true.…

Fifty-five years earlier Louis had written to a girlfriend of his saying, “I have … managed to have one short story accepted by a small magazine one finds on the newsstands. It pays rather well but is somewhat sensational. The magazine … is generally illustrated by several pictures of partially undressed ladies, and they are usually rather heavily constructed ladies also. It is called 10 Story Book. My story was a realistic tale of some hoboes called “Death, Westbound.”

Now, I knew for a fact that Dad was trying to impress this gal like all get out. But it seemed like he was talking about the same story that he mentioned many years later. A check of his list of story submissions for the nineteen thirties revealed that he had continued to submit work to 10 Story Book for the next several years.… Not what you’d expect if they had “folded.” Much later in life, had Louis felt compelled to mention this early moment of triumph but at the same time deny his connection to the magazine’s somewhat sleazy content?

A number of searches showed that very few copies of 10 Story Book existed in libraries or public archives. So I began to put the word out to magazine aficionados, pulp collectors, and the fairly offbeat subculture of antique pornography collectors. About five years passed with little result other than occasionally calling or e-mailing various people and reminding them that I was still interested. But one day my in-box divulged a scan of “Death, Westbound” by Louis D. Amour. One of my contacts had finally come through. I don’t know if the name, D. Amour, was a mistake or an early attempt at a pseudonym, but this was Louis L’Amour’s first recorded sale.

Sensational photos (for the 1930s) aside, Dad seems to have been in good company; Jack Woodford is listed in the table of contents of the edition and I assume that this is the novelist, screenwriter, and short-story master of Jack Woodford on Writing fame. Other famous writers of the early twentieth century are also reputed to have been published here, too; 10 Story Book following a model later used by Playboy, where the promise of unclothed women draws in readers who otherwise would never have bothered with literature at all; and the literature gave the magazine some class and protection from the opinions of moralists and pro-censorship types.

In this collection, “Death, Westbound” begins a cycle that will carry the reader through stories that relate to many actual events in Louis’s early life. It should not be assumed that these stories are always literally true but they are a snapshot of the times—the 1920s and 1930s—and how Louis L’Amour experienced those times. Greatly influenced by Jack London, Eugene O’Neal, and later John Steinbeck, Louis began his career by trying to document the era that he lived in. Whether “Death, Westbound” is a “true story” or not, Louis did ride the side-door Pullman’s of the Southern Pacific on many occasions; from Arizona to Texas and back again, and from Arizona to California even more often.

The stories “Old Doc Yak,” “It’s Your Move,” and “And Proudly Die,” soon followed, and were drawn from actual people that Louis knew in the time he spent waiting for a ship or “on the beach,” as the sailors called unemployment, in San Pedro, California. Louis wrote of that time in an introduction from Yondering: “Rough painting or bucking rivets in the shipyards, swamping on a truck, or working ‘standby’ on a ship were all a man could find. It wasn’t enough. We missed meals and slept wherever we could. The town was filled with drifting, homeless men, mostly seamen from all the countries in the world. Sometimes I slept in empty boxcars, in abandoned buildings, or in the lumber piles on the old E. K. Wood lumber dock.”

The piled lumber Louis mentions often left gaps or overhangs, some well off the ground, which were shelter of a sort. But if you had a few cents, the vastly preferred place to spend the night was the Seaman’s Church Institute, sort of a YMCA for seamen. “Survival,” another story of that time, was based on a story that Louis had heard in his time around the Seaman’s Institute, but many gaps in the narrative have been filled with his own material, and it is populated with mostly fictional characters.

Louis left San Pedro on a voyage that would eventually take him around the world and “Thicker Than Blood” and “The Admiral” are drawn from that experience. I don’t know if the events in these stories are true in whole or in part, but buried in among Louis’s papers I found the following photographs …

To the right is Leonard Duks, first mate of the SS Steel Worker and Louis’s nemesis on a voyage that took them from San Pedro west to Japan, China, the Dutch East Indies, the Federated Malay States, Aden Arabia, the Suez Canal, and on into Brooklyn, New York. I don’t know if Duks truly lived up to his fictional reputation in “Thicker Than Blood,” but Louis didn’t like the man and appointed himself as a spokesman for the crew’s complaints about the unbelievably bad food and other various working conditions.

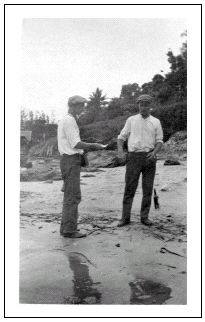

The ship did not call in Shanghai twice, so much of “The Admiral” may be fictional. However, the note on the back of the next photograph suggests otherwise. It reads, “Tony and Joe taken on the beach at Balikpapan (Borneo). Tony is the one in ‘The Admiral.’ ”

Additional photographs from Balikpapan include one of the Steel Worker at anchor with much of what looks like their cargo of pipe in the foreground …

And the following, which reads, “Luflander, Malay barber, myself at eighteen, Balikpapan, Borneo.”

“The Admiral” was originally published by Story, a magazine which was very prestigious at the time, and Louis’s being included raised some favorable comment. Dad, more than anything, wanted to continue in this vein. He imagined a cycle of stories about San Pedro and another cycle that took place in Shanghai, both utilizing loosely interconnected sets of colorful characters; hoboes and seamen, soldiers of fortune and gangsters, historical characters and working stiffs just trying to get by.

However, he also needed to get paid. The literary magazines paid on publication and while that was bad enough when the stories were scheduled months ahead of time, often they were not scheduled at all: the story was accepted but the editor had no idea when he would run it and thus no idea when he would pay. The pulp magazines, which published a far less literary fare, paid better and, more important, they paid faster, sending out a check the moment they accepted a story. Ultimately, Louis found this combination hard to beat. At times, though, he did wonder rather wistfully about what kind of career he would have had if he’d been able to keep writing in this more “personal adventure, personal experience” style.

“The Dancing Kate” seems to mix some of the more realistic elements of those “personal experience” stories with those of a pulp adventure while “Glorious! Glorious!” returns to the more anti-heroic style. Louis could not have participated in the Riffian War where the forces of Abdel-Krim fought both the Spanish and the French Foreign Legions but the Steel Worker did sail the Moroccan coast during its final days. “Off the Mangrove Coast” has a plot similar to a story that Louis told about his own life, a story where he and several others unsuccessfully attempted to salvage a riverboat that was supposedly full of the treasure that a rajah from the Federated Malay States took with him when some form of uprising forced him from power. “The Cross and the Candle” is also based on an actual experience, though I do not believe that Louis was there for the climax of the story or that he played a part in solving the murder of the man’s ill-fated sweetheart.

“A Friend of the General” is interesting because there is no indication of when it was written. I suspect that Louis wrote it quite late in his career, possibly in 1979 or ’80, in order to include it in the collection Yondering. Louis’s unit, a Quartermaster’s Truck Company, was based out of Château de Spoir, home of the Count and Countess Dulong du Rosney. The count and countess had indeed moved into a gardener’s cottage across the road from the château itself. The “cottage” (more appropriately, the home of the estate manager) was of a style and size that would have attracted notice even in Beverly Hills, so they were nicely housed even though first the German and then the American army had taken over the main residence. The Countess Dulong du Rosney has no memory of Lt. Louis L’Amour, Parisian black-market cafés, or the mysterious “General,” but she still may have been the model for the countess in the story. When I spoke to her a few years ago it was obvious that she had that same sense of unflappable self-assurance. The story of the ill-fated arms merchant Milton is one that Louis told many times as if it were true, suggesting that he was teaching boxing at a fencing and martial arts academy in Frenchtown (a section of old Shanghai) at the time.

With “East of Gorontalo” we bid adieu to the group of stories based closely on Louis’s life experience, and launch into three different series he created between 1938 and 1948 for Leo Margulies at Standard Magazines, a company that owned Thrilling Adventures and many others. Although there are few of Louis’s personal experiences in the stories of tramp freighter captain Jim Mayo and the “pilots of fortune” Turk Madden and Steve Cowan, many of the locations were places that he had visited during what Louis called his “knocking around” period. In fact, in his collection Night Over the Solomons, Louis claimed that in the case of Kolombangara Island in 1943, a story of his had closely echoed reality:

Shortly after my story [“Night Over the Solomons”] was published the Navy discovered this Japanese base of which I had written. I am sure my story had nothing to do with its discovery and doubt if the magazine in which it was published had reached the South Pacific at the time.

My decision to locate a Japanese base on Kolombangara was not based on any inside information but simple logic. We had troops fighting on Guadalcanal. If the Japanese wished to harass our supply lines, where would they locate their base?

From my time at sea I had a few charts and I dug out the one on the Solomons. Kolombangara was the obvious solution. There was a place where an airfield could be built, a deep harbor where ships could bring supplies and lie unnoticed unless a plane flew directly over the harbor, which was well hidden. No doubt the Japanese had used the same logic in locating their base and the Navy in discovering it.

He went on to note that while his hero reached the island from a torpedoed ship, both an American pilot and John F. Kennedy had been stranded in the vicinity of Kolombangara under circumstances that would have fit his fictional story to perfection.

Louis’s knowledge of the operation and layout of Mayo’s ship, the Semiramis, came from the time that he had spent as an able-bodied seaman on similar ships and his years of working as a longshoreman and then a Cargo Control Officer at San Francisco’s Port of Embarkation during the early days of World War II. The interest in aircraft and the appreciation of the freedom of a tramp flier was gleaned from his good friend Bob Roberts who had lived that life, though never in the Far East.

As Louis moved on through the next two stages of his career, writing crime stories and then westerns, many of the elements found in these early adventure stories continued to appear. His fictional Far East was crowded with types modeled on American gangsters, similar to the crooked sports promoters and gamblers in his stories of the boxing ring, and the Semiramis and its crew could almost stand in for a more racially diverse version of one of the beleaguered cattle outfits that his western characters later rode for. In a way his transition from one genre to another was more of a blurring of the lines or a recombining of elements.

For a more in-depth look at all of these stories and more information on this collection visit us at louislamourgreatadventure.com.

Over the next three years we will continue this program with the publication of The Frontier Stories, Volume Five in 2007. The following year we will bring out a collection of crime and boxing stories and then, finally, one last collection of westerns, The Frontier Stories, Volume Seven. I certainly hope you enjoyed this collection and that you find these next few equally pleasurable.

Beau L’Amour

Los Angeles, California

2006