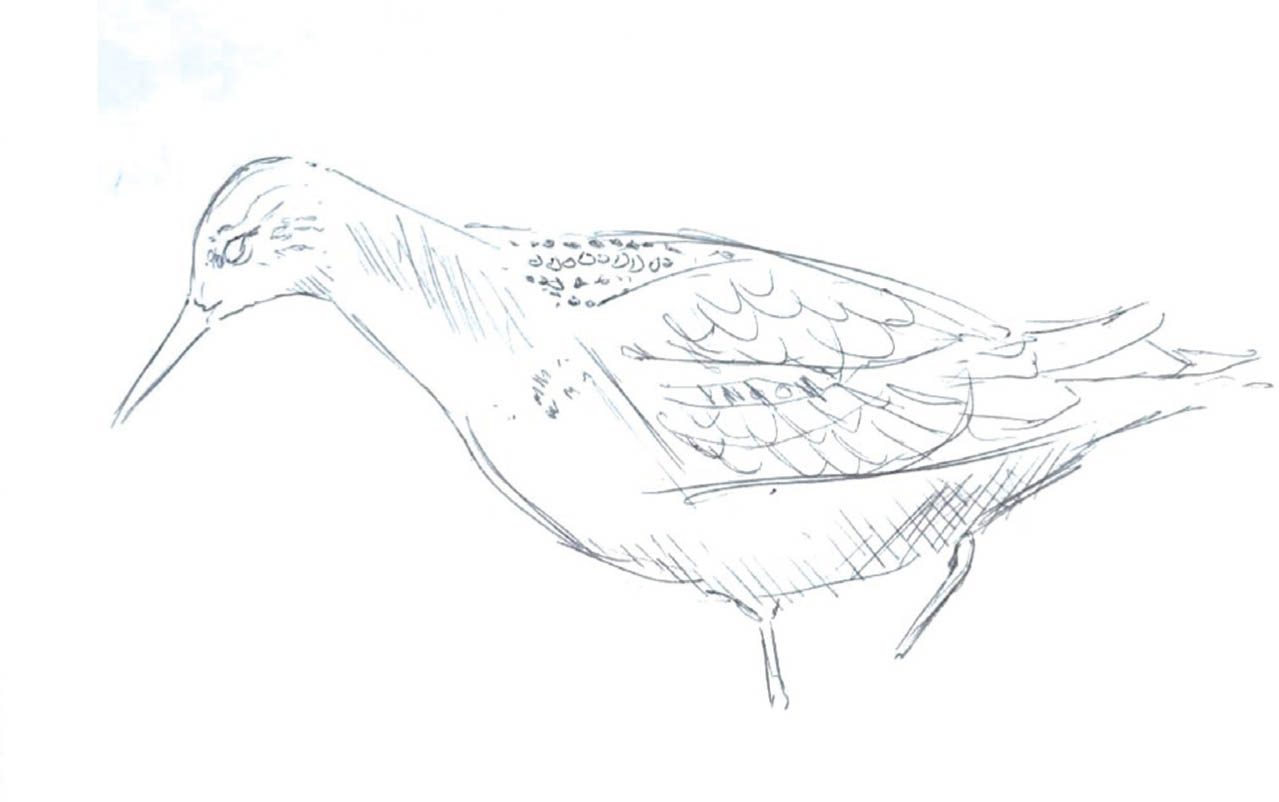

Adam Bowley: red-footed falcon sketches.

DRAWING TECHNIQUES

That which we persist in doing becomes easier to do; not that the nature of the thing itself is changed, but that our power to do is increased.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

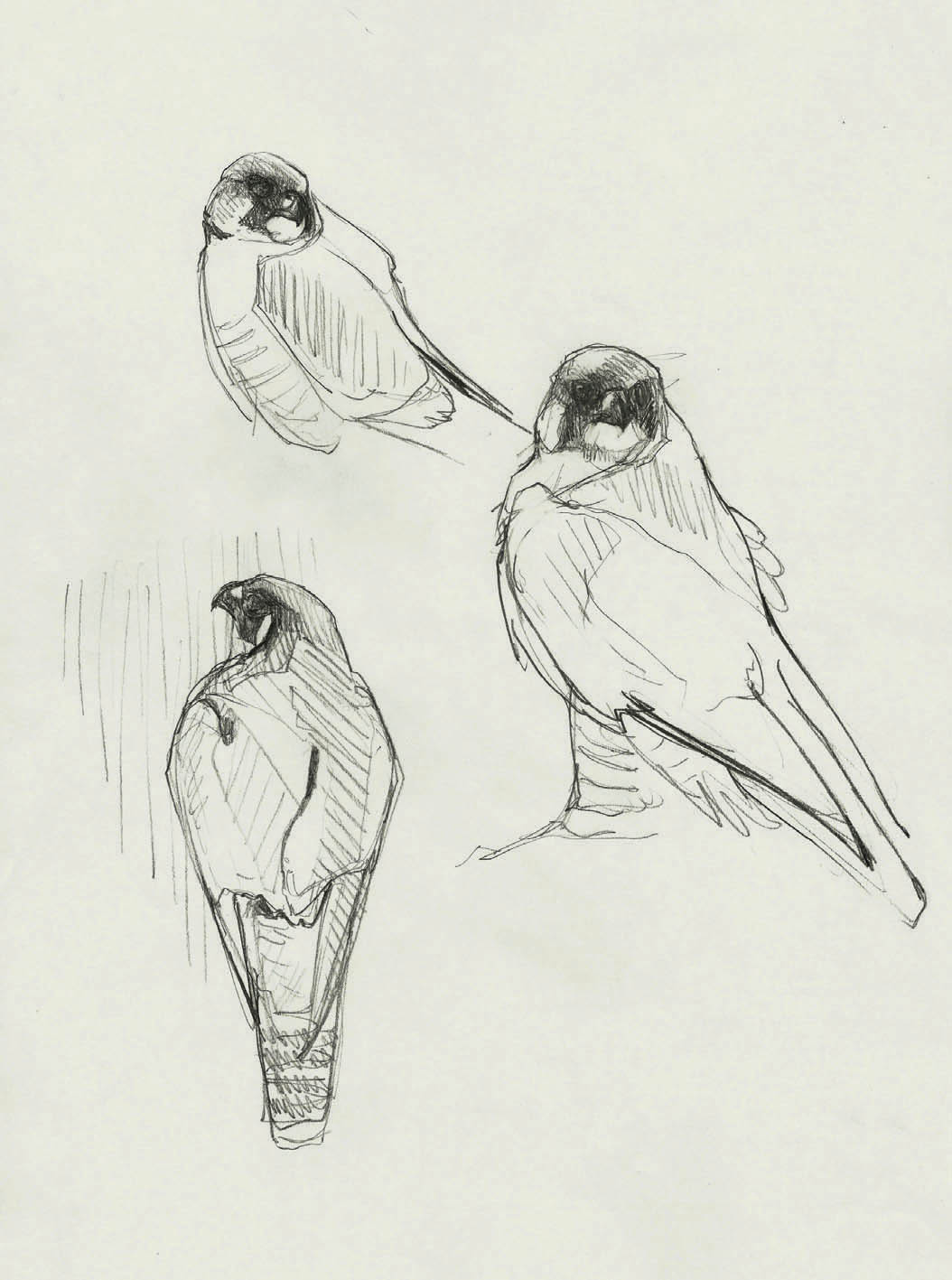

Debby Kaspari: purple martins (ink).

Developing drawing skills can be a lifelong process for the would-be artist. The basics, however, may be simplified. There are only two types of line – curved and straight – and if one can draw both of these, then there is no reason why any kind of drawing cannot be attempted. As children, we were encouraged to draw and we did so without inhibition. We were able to make representational images with little or no reference other than our imagination, or mind’s eye. If we could make drawings as children, with no reference, why then does it appear to be so very difficult to draw when reference is introduced? With something to look at and relate our drawings to the process ought to be easier – but it seems not to be. When starting out we can easily be distracted by too much visual information, so much so that the brain becomes overloaded and our attempts to convert what we can see into a linear depiction on paper flounder. Learning to draw isn’t so much learning how to make a line on paper. It is more about learning to ‘see’. What is meant by this is how to distil from all the visual information presented a simplified version, one which can be described in two dimensions onto a surface.

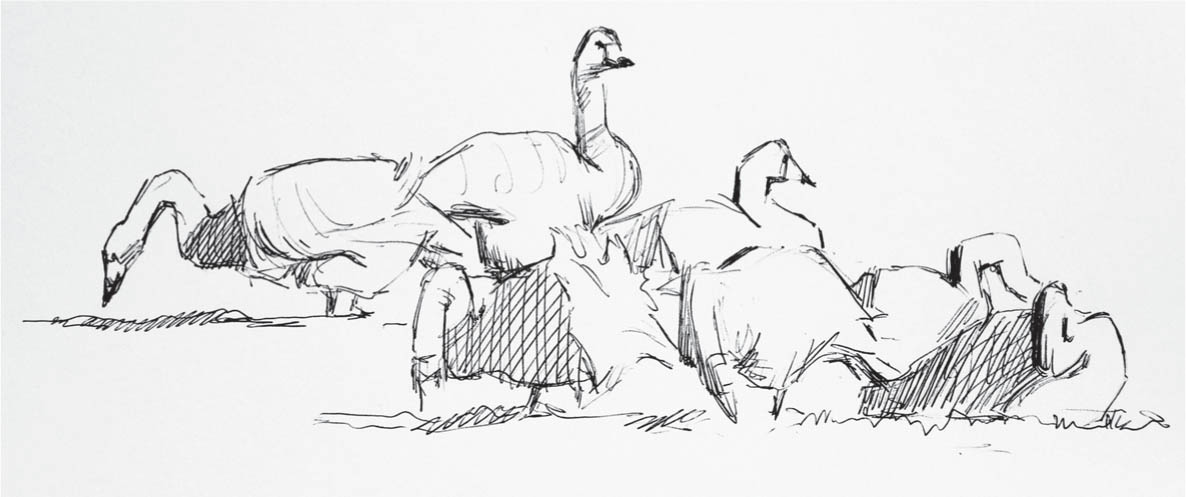

Tim Wootton: whooper swans in strong light and a stiff breeze. Biro drawing; the structure of the birds described in simple terms, outline and cross-hatch.

Birds move. They move a lot and often they move quickly. If one is to attempt to portray birds doing what they do, then it is important to learn how to ‘see’. What I mean by this is how to learn to capture in your mind’s eye the shapes, forms and action of the living creature. As with all skills, this aspect of drawing can be nurtured and developed. The following exercise helps to develop observation and recollection of images.

Set up a few objects as in a still life. Study the shapes in front of you: not just the objects, but the spaces between them and their interrelationships.

Set up a few objects as in a still life. Study the shapes in front of you: not just the objects, but the spaces between them and their interrelationships.

Here is the set-up I put together. You can use any combination of objects you wish.

Concentrate for three minutes on the assemblage. Then, without looking back at the set, immediately draw what you can remember. In your mind’s eye, try to picture the scene as it appeared. Continue to draw for as long as you feel you are still adding valid information to the drawing. When you can remember no more from the set, stop working.

Concentrate for three minutes on the assemblage. Then, without looking back at the set, immediately draw what you can remember. In your mind’s eye, try to picture the scene as it appeared. Continue to draw for as long as you feel you are still adding valid information to the drawing. When you can remember no more from the set, stop working.

Now compare your impression to the set in front of you. There will probably be some elements drawn fairly accurately and others not so. Spatial proportions are most likely to be awry and even the number of objects may be incorrect.

Now compare your impression to the set in front of you. There will probably be some elements drawn fairly accurately and others not so. Spatial proportions are most likely to be awry and even the number of objects may be incorrect.

Now spend thirty seconds looking at the set again. Make a drawing from life, referring constantly to the set. Look at the spaces between the objects (the ‘negative shapes’), look for invisible lines that connect different objects together, such as parallel lines, geometric shapes where objects interconnect or objects sitting along the same plane. Spend five to ten minutes really investigating the set using linear drawing only. When you’re happy with your representation – stop!

Now spend thirty seconds looking at the set again. Make a drawing from life, referring constantly to the set. Look at the spaces between the objects (the ‘negative shapes’), look for invisible lines that connect different objects together, such as parallel lines, geometric shapes where objects interconnect or objects sitting along the same plane. Spend five to ten minutes really investigating the set using linear drawing only. When you’re happy with your representation – stop!

Four-minute drawing whilst referring to the set.

Next, follow the first exercise you did. Again, study the set for three minutes. Look at all the shapes presented – positive and negative. Try to make visual patterns in your head.

Next, follow the first exercise you did. Again, study the set for three minutes. Look at all the shapes presented – positive and negative. Try to make visual patterns in your head.

Turn away from the set and make another drawing. Refer to your immediate memory of the objects and try to recall the shapes you drew whilst you were drawing from life. Continue to draw until you feel you’ve finished and cannot add any further information to the piece.

Turn away from the set and make another drawing. Refer to your immediate memory of the objects and try to recall the shapes you drew whilst you were drawing from life. Continue to draw until you feel you’ve finished and cannot add any further information to the piece.

Now compare all three drawings together. The middle drawing will probably be the most accurate (you were referring directly from the objects so it ought to be, really), but note the difference in the amount of information your last drawing contains in relation to the first.

Now compare all three drawings together. The middle drawing will probably be the most accurate (you were referring directly from the objects so it ought to be, really), but note the difference in the amount of information your last drawing contains in relation to the first.

Three-minute drawing from memory.

The constant study and reappraisal of the objects has improved your ability to ‘see’ the shapes with more clarity and precision at each stage. If you were to repeat the process several times, your understanding of the scene would increase at each and every stage.

This principle can be applied to any form of drawing from life and constant practice is a sure key to successful results when drawing birds. The hardest bit is making a start.

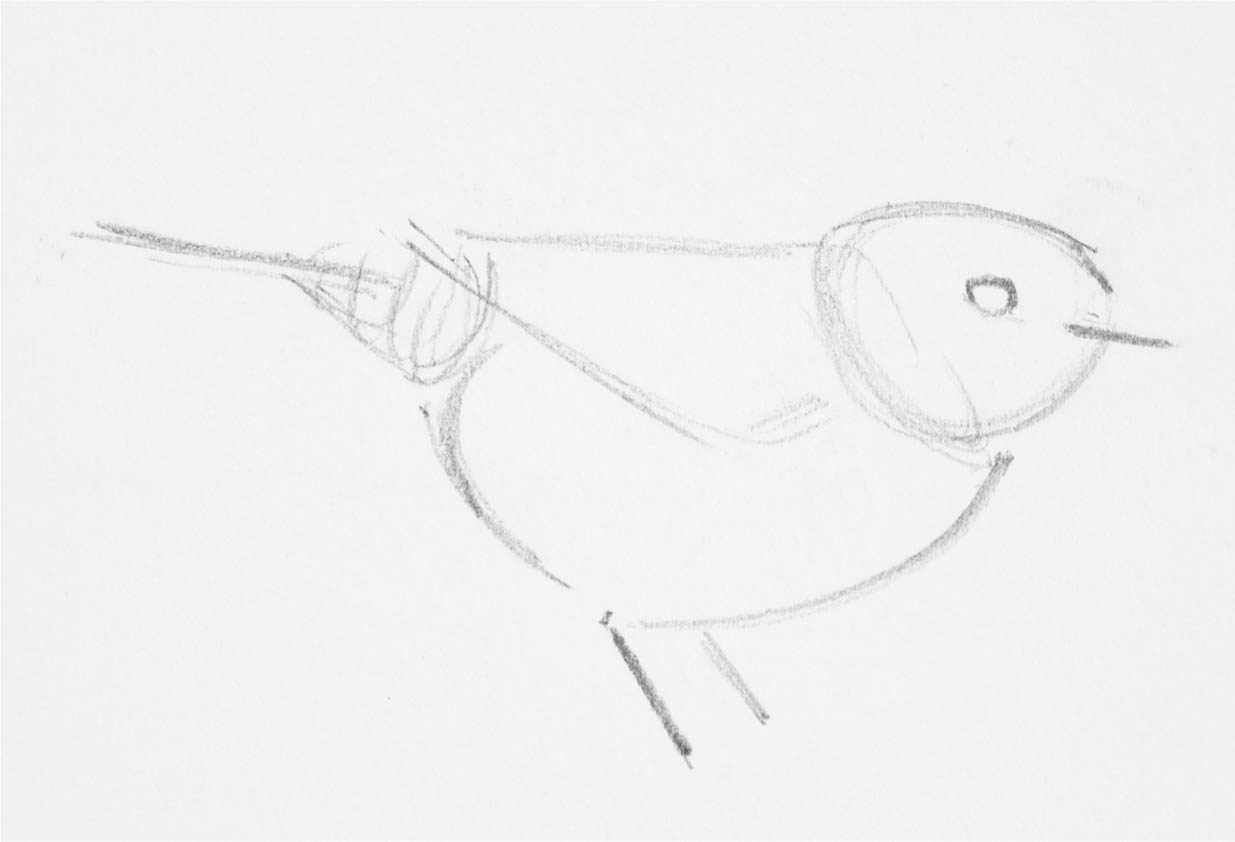

We must all be familiar with the traditional ‘two circle’ approach to drawing birds, depicting head and body. Fundamentally, this can be a useful approach to breaking the tension between your pencil and the foreboding expanse of the unmarked page. Usually the two circles are arranged one atop the other; this is where a touch of subtlety is required. Bird species have various shapes of skulls (and bills), which are connected to their bodies by the neck; they also have specific characteristics due to the number of vertebrae and habit of the bird (more of which in the anatomy section).

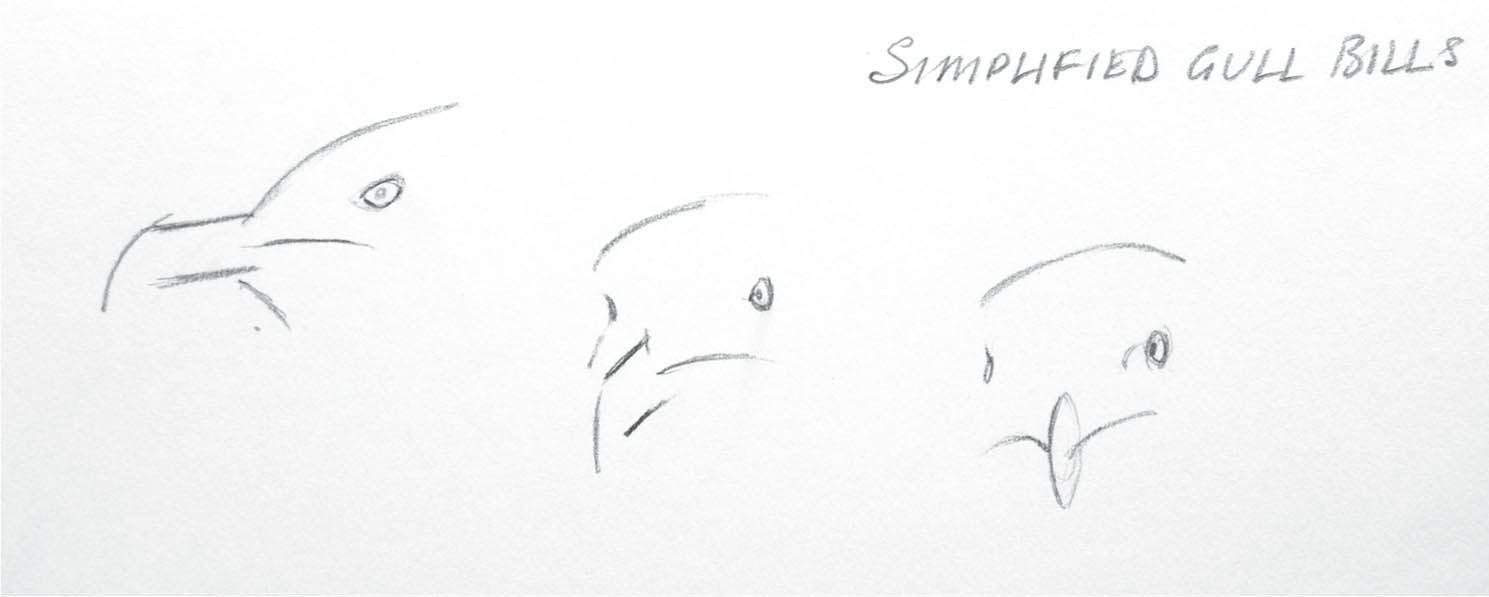

Birds’ beaks can cause the draughtsman many problems, so it may be helpful to use a shorthand method of representing these features. Simplistic shapes, lines of different lengths and breadths, cones and ovals may be interpreted as beaks and bills. What is more important is the particular angle of the beak, or its relationship to eye position and overall head shape. Body shape, leg length and a suggestion of how the creature moves are what will ultimately determine the character of the subject; something which is called ‘jizz’ (or ‘giss’ – general impression of size and shape) in birdwatching parlance.

Getting the exact facial pattern can be crucial to capturing the character of the bird. Knowledge of the different features of the head can help to get the precise arrangement of lights, darks and colours. The dark fringe to the white cheeks of the blue tit is a helpful pointer in describing the important line delineating the join of the head and the body. The white wingbar also accentuates the curve of the wings as they fold across the back.

Simple ways to depict bill shapes.

SIMPLE GEOMETRIC SHAPES

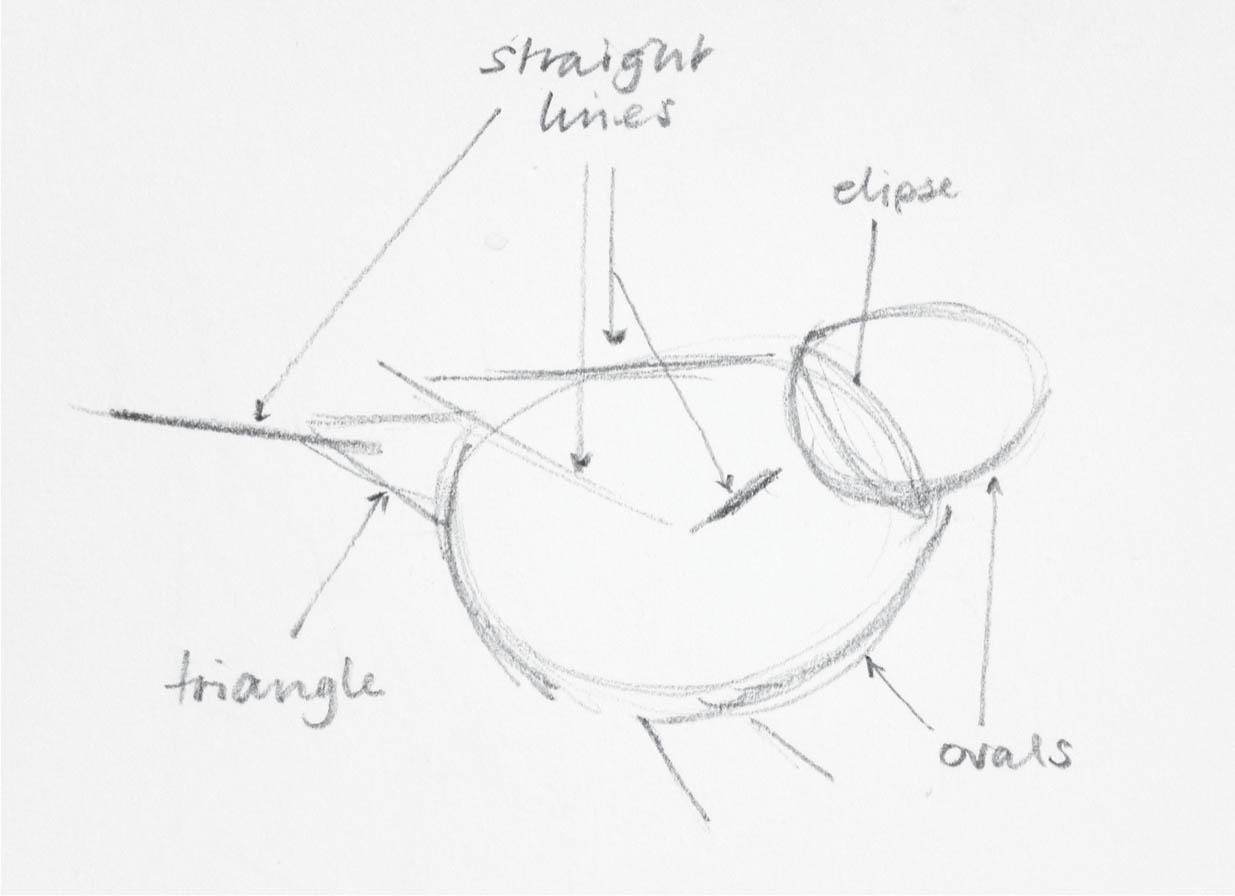

The ability to draw ovals, cones, cylinders and parallelograms is an essential part of the draughtsman’s toolkit. When drawing birds you will notice, with a bit of practice, that these shapes occur regularly. Recognizing where and when straight lines occur can help in ‘catching’ a pose, helping to create dynamism in the drawing. The fundamental lines and shapes will generally be curves and straight lines – not only describing the outlines of the bird, but also following external surface features such as wing edges and breast markings.

So it makes sense to be able to draw a selection of lines and to know a few techniques that can help when it comes to drawing the birds.

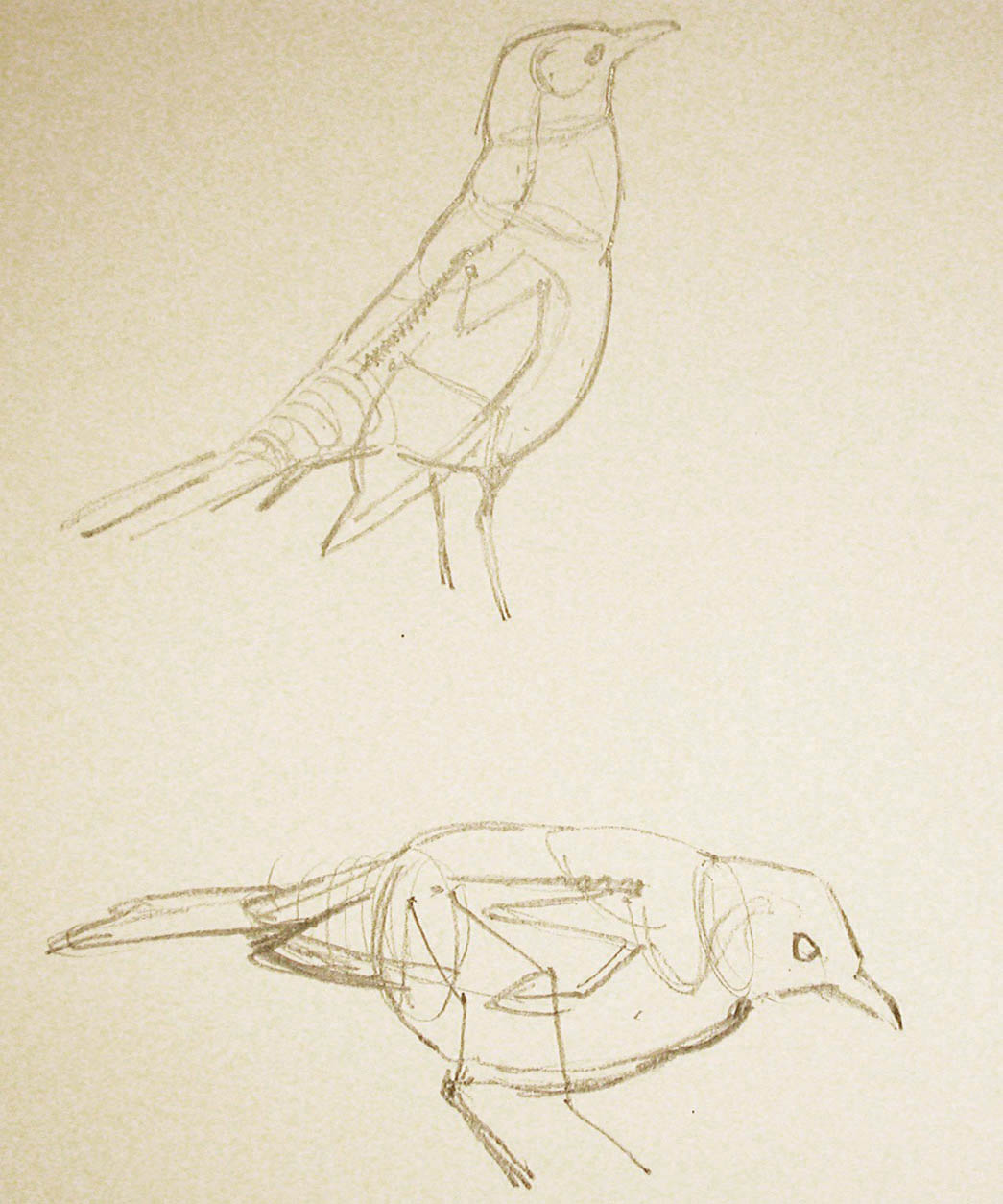

Tim Wootton: construction drawings of a blackbird. The outer shape of the bird is drawn using straight and curved lines, and by using spirals, cones and ellipses the drawing can have a sense of ‘roundness’ (that is, the curves of the bird don’t stop at the outline). Look at how the ellipse connecting the head with the body describes both the angle and the shape; there are also imagined lines suggesting the wing and leg bones.

Simplified versions of two of the drawings on the previous page, showing how the outlines could be derived.

WARM-UP EXERCISE AND CONTROL PRACTICE

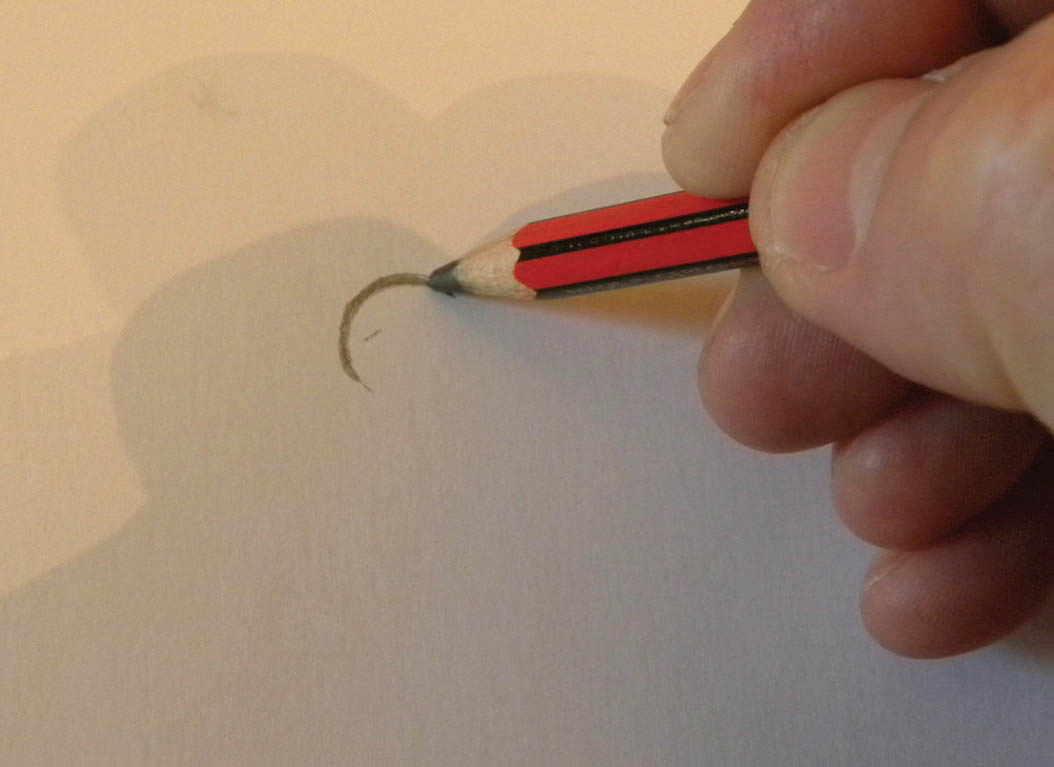

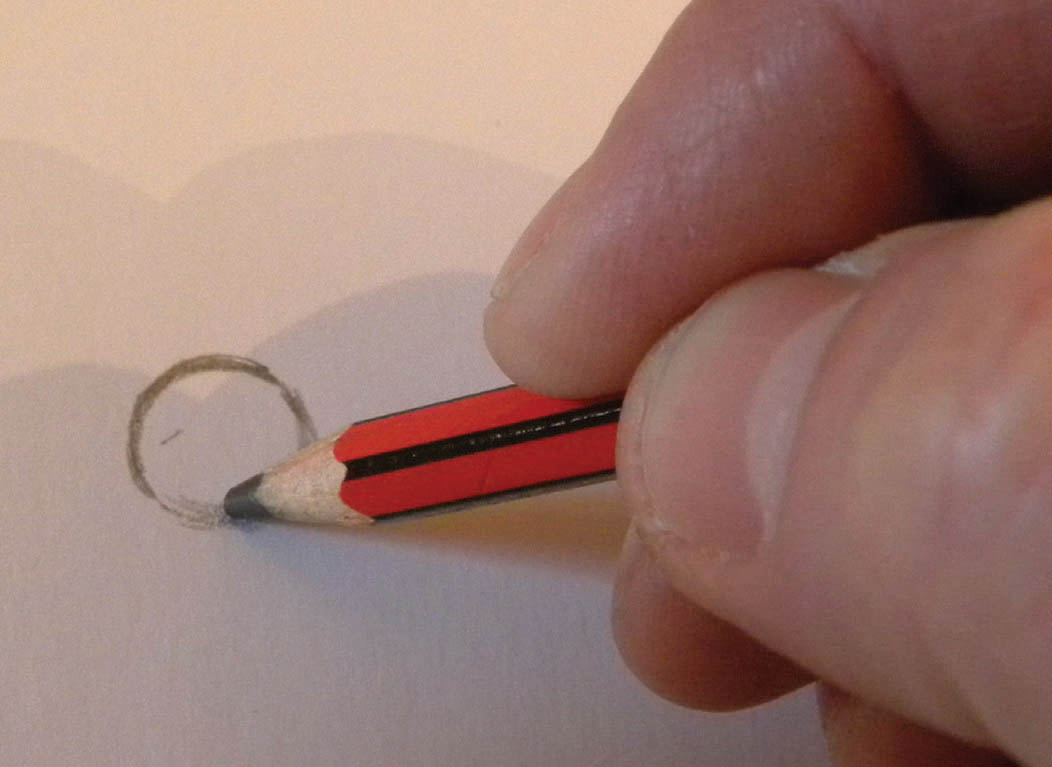

Constructive scribbling and doodling can be beneficial to good drawing and, besides being useful for practice, are also handy warming-up exercises prior to starting drawing. These simple activities give your hand–eye coordination a nice little workout and also break down the tricky transition movements we all have when drawing. By this I mean we all find drawing a curve much easier when we are ‘inside’ the curve (see above) but when we get to the point that we have to start pulling the pencil down towards us and then pushing away, the curve tends to lose its smoothness. Practising drawing circles helps to iron out this problem.

Practise sketching the circle – making light approximations where you think the circle ought to be; only when you can see the circle, commit to a darker line. This use of light pencil marks is very useful where you are tentative about where the ‘true’ line ought to be and comes in handy when drawing from life.

Practise sketching the circle – making light approximations where you think the circle ought to be; only when you can see the circle, commit to a darker line. This use of light pencil marks is very useful where you are tentative about where the ‘true’ line ought to be and comes in handy when drawing from life.

Circle exercises.

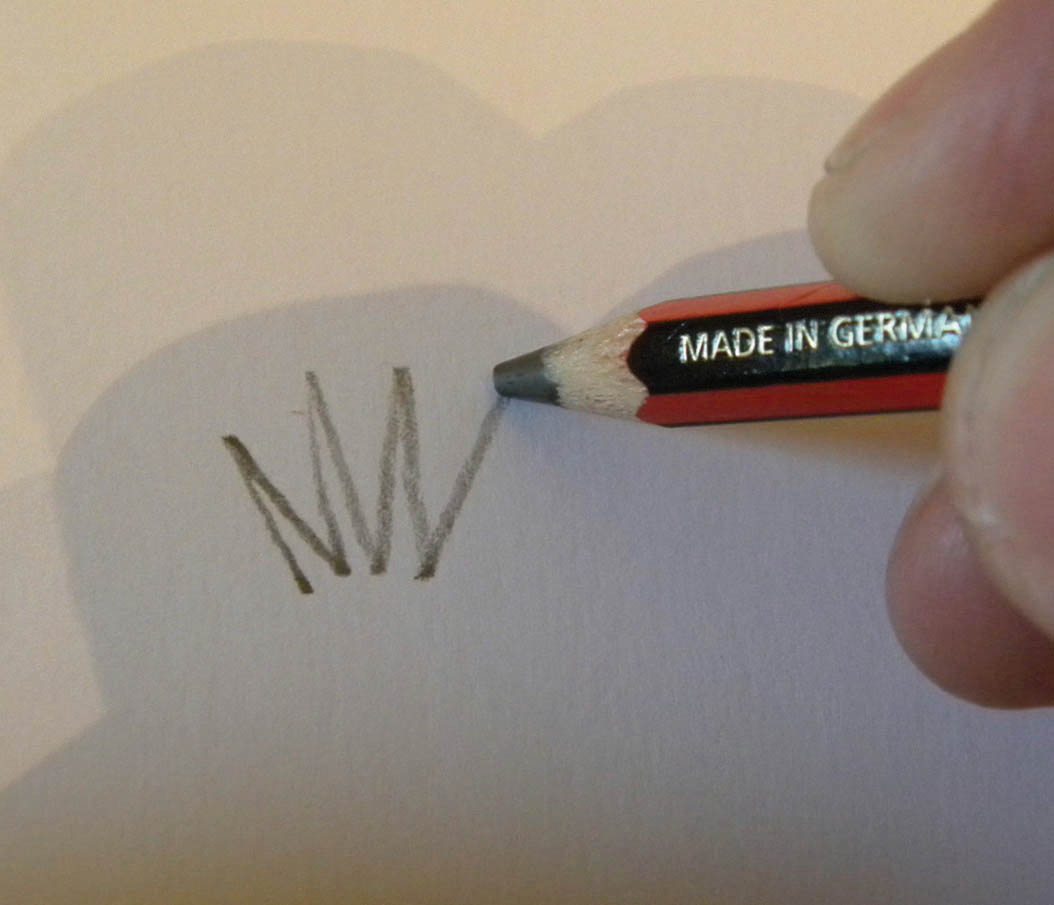

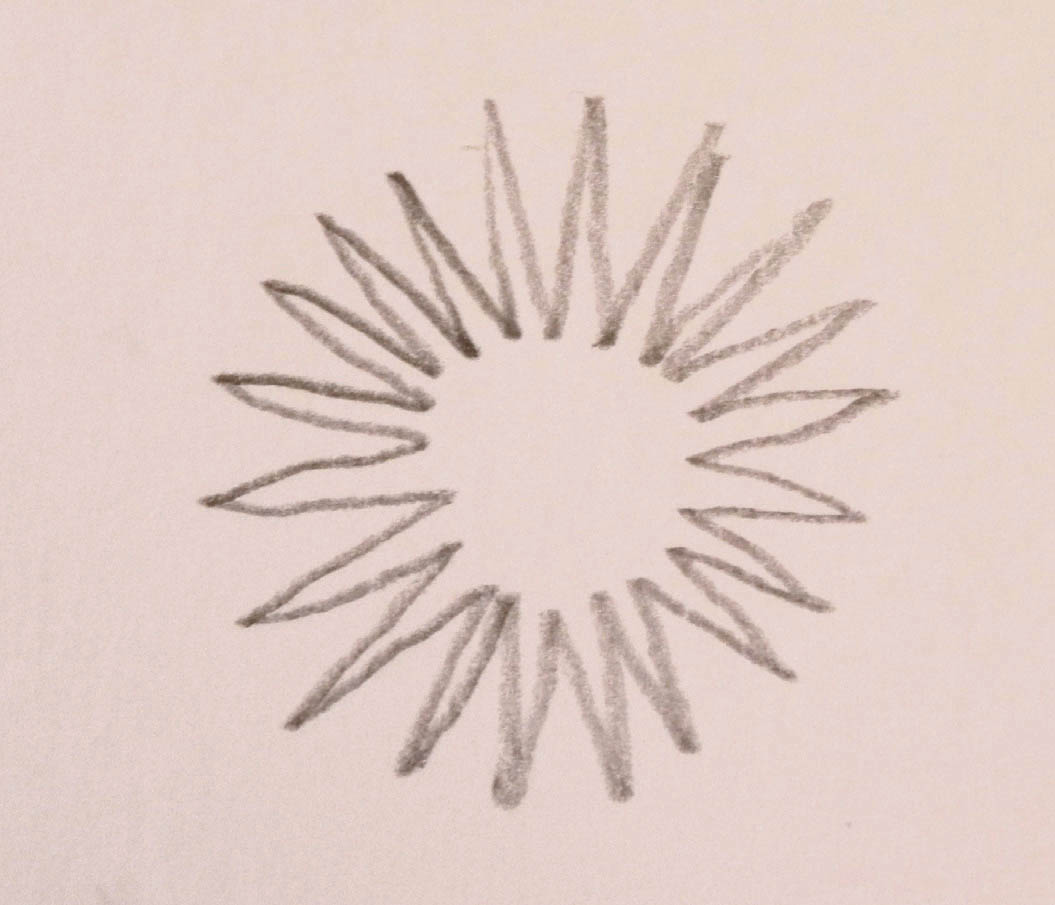

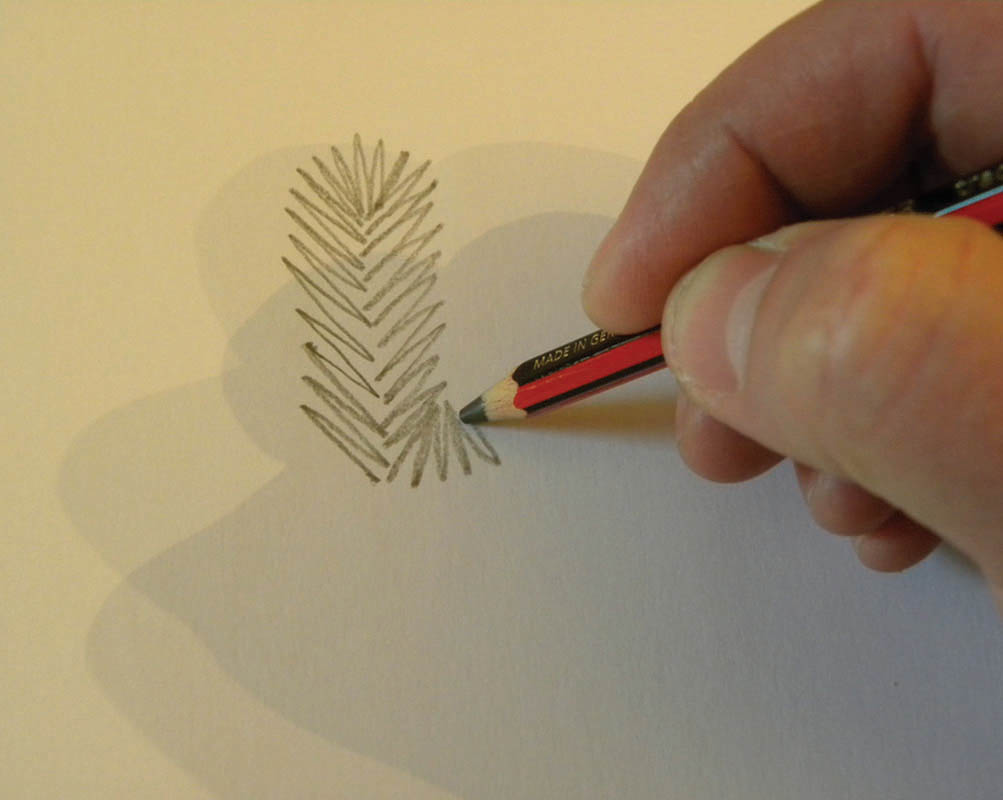

The next exercise is a step on from circle drawing and requires much greater dexterity and helps to develop the way you plan where your pencil is going to go, not just for the immediate line but also many lines ahead. You have to imagine two concentric circles and then use a radiating scribble to join the two together. You ought to be aiming for smooth outer and inner edges and evenly spaced spokes.

The next exercise is a step on from circle drawing and requires much greater dexterity and helps to develop the way you plan where your pencil is going to go, not just for the immediate line but also many lines ahead. You have to imagine two concentric circles and then use a radiating scribble to join the two together. You ought to be aiming for smooth outer and inner edges and evenly spaced spokes.

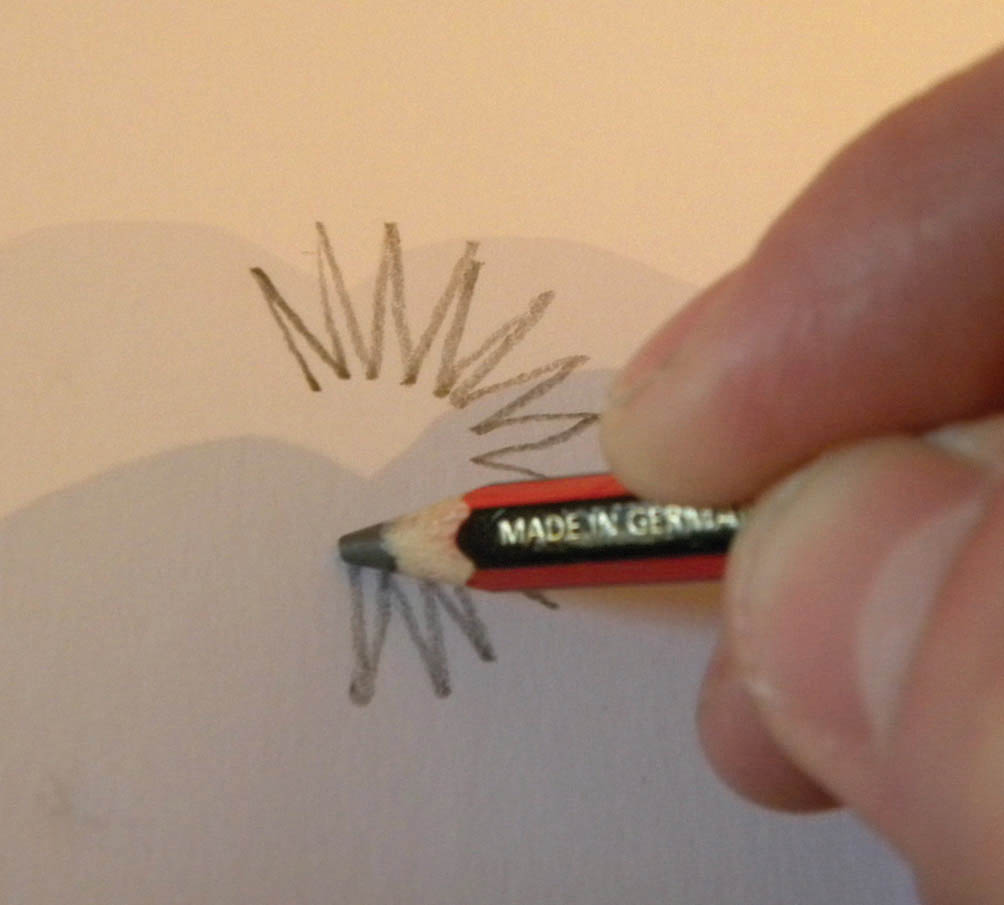

Finally, the loop exercise brings together the previous disciplines, combining them into a practical and useful skill that has many applications in all types of drawing. You will be using a push and pull motion along two opposing diagonals, will have to visualize parallel lines and even curves and need to keep the strength of the lines and the overall shape of the finished loop nicely balanced. Practising this will improve your drawing and the way you see shapes on the canvas.

Finally, the loop exercise brings together the previous disciplines, combining them into a practical and useful skill that has many applications in all types of drawing. You will be using a push and pull motion along two opposing diagonals, will have to visualize parallel lines and even curves and need to keep the strength of the lines and the overall shape of the finished loop nicely balanced. Practising this will improve your drawing and the way you see shapes on the canvas.

Star exercises: the edges of the spokes form two concentric circles.

Loop exercises.

Photographs have been used by artists, both as reference and, occasionally, inspiration, since the process was invented. The Impressionists were quick to recognize its potential, together with landscape and portrait painters, and it has particular relevance to nature study and for the bird artist. For some artists the photograph should only ever be referred to as a last resort, perhaps to check a specific detail of plumage; for others the photograph may be the starting point and even the main inspiration for making a piece of art.

Opinions are divided regarding the use of photographs for reference and it is quite possible that artwork produced solely from photographic reference could be in danger of missing something – vitality, life, energy, for example. Perhaps more importantly though, recreating the photographic image without any attempt at interpretation may become the overriding aim for the artist at the expense of more creative aspirations. There is no doubt, however, that photographs certainly have a role to play in drawing and painting birds.

The suggestion to ‘draw what one sees, not what one knows to be there’ is a fine sentiment. But it depends on how well one can see the subject. I mean, a bird moving or performing a complex action such as preening under its tail, or wing and leg stretching, creates many unusual and perhaps unfamiliar shapes. Certainly a study of anatomy can help to disentangle the visual clutter that the artist is faced with, but from time to time, more detailed study of a particular process may be required. This is when photography – still and cinematic – can be a valuable resource.

When we become familiar with which actions give rise to what general shapes by reference to photographic material, then these actions when observed in life will become more easily decipherable. To deny ourselves the use of photographs when we are trying to understand the structure of birds seems to me a puritanical line. After all, we knew nothing of the way birds’ wings perform in flight until the advent of slow-motion photography, and quadrupeds were assumed to gallop with two feet together. These aspects of biomechanics are now so ingrained in our consciousness that images of moving creatures painted prior to the revelations of movement seem ungainly and crude. We now accept these facts as truths and we need to acknowledge the work done by those photographic pioneers in discovering important aspects of movement.

Regarding the use of photographic reference, here is what Robert Bateman (Robert Bateman on Painting) says on the subject:

I could never understand why some artists shrank from using photographs. Many, many years ago, I can remember students asking in hushed tones, ‘Is it all right to use photographs?’ I have never heard of a good reason not to. One person said that it could make your work tight and inexpressive. Well, my wife uses photos for her painting and she is a bold, abstract artist and very expressive. Others whose work is loose and free and painterly do as well. In fact, in the last several decades I don’t ever hear that question. Everybody uses photographs if they are at all interested in realism. Even modernists and postmodernists such as Warhol, Rauschenberg and Richter show photo-based paintings which are in the collections of big city museums.

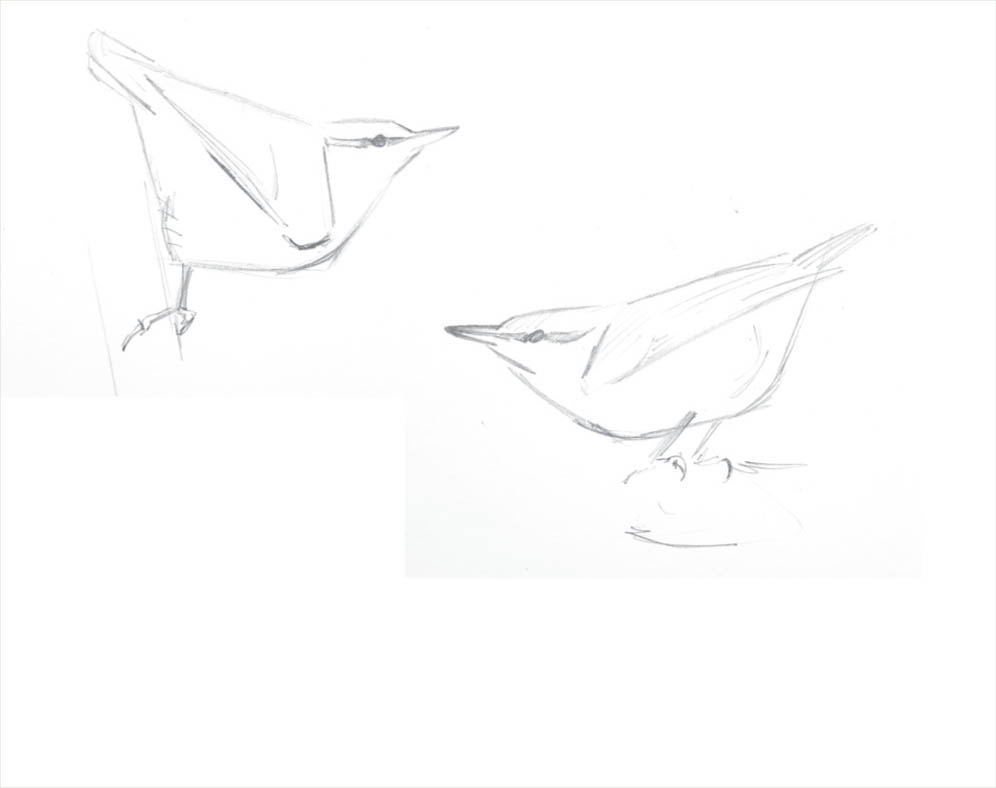

EXERCISE USING PHOTOGRAPHS OF A NUTHATCH

Adrian Dancy: photographs of a nuthatch.

Tim Wootton: construction drawings of a nuthatch.

Look for the major shapes that contain the form and describe the main areas of structure and light/dark. Follow the construction drawings and notice how they relate to the shapes on the actual bird. The second stage has a few more lines expressing a little bit of detail.

Try this approach to interpret photographs and then, once you’ve built up your confidence in working out what and where the main shapes are and your ability to draw them accurately, take your sketchbook outside and see how the technique translates from a flat and inert image to a three-dimensional one. Choose birds that are settled and fairly motionless so you have time to work out the shapes and build up your confidence.

Debby Kaspari: tundra swan. Drawing made directly from the sleeping bird.

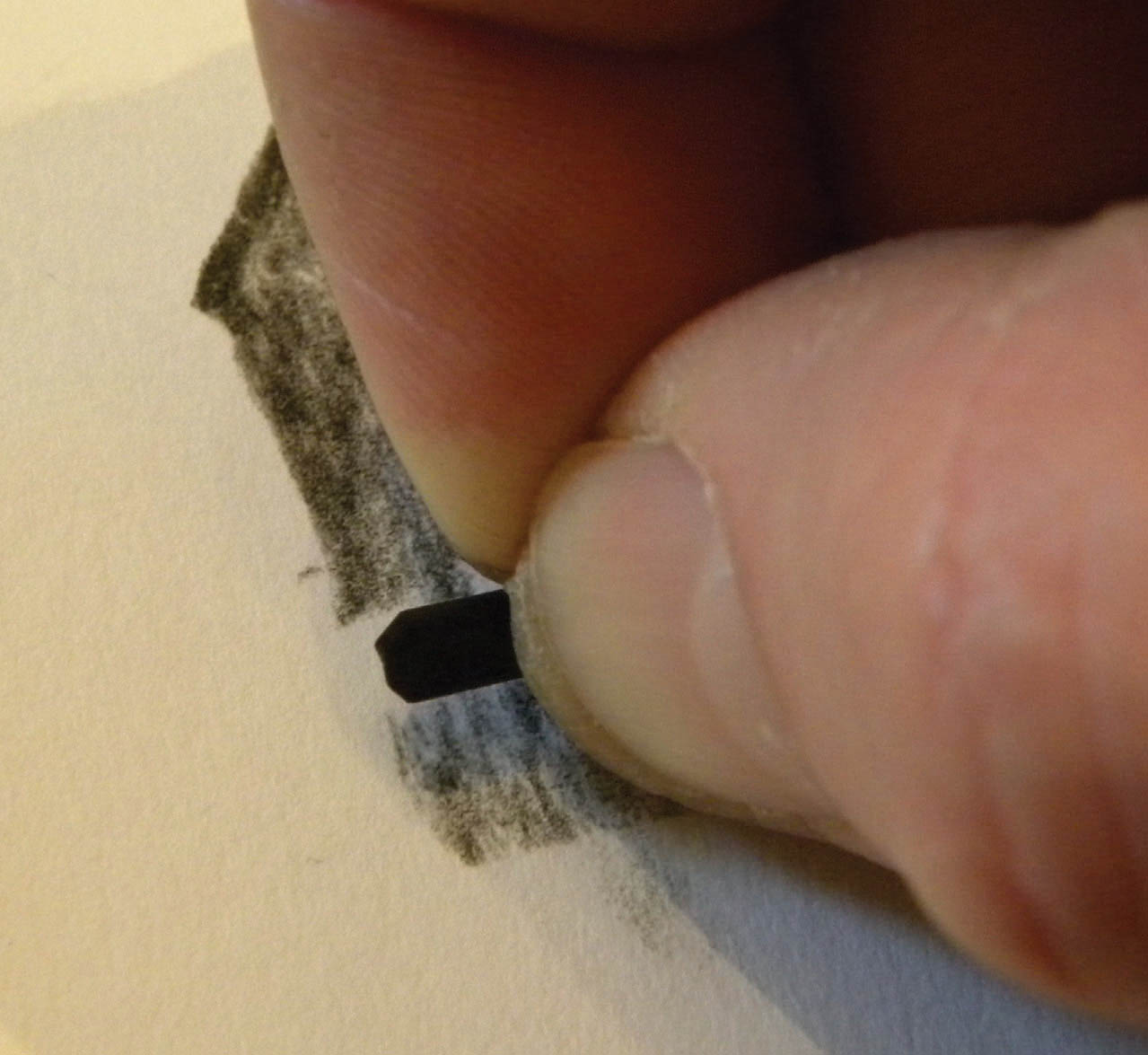

Alan Dalton: grey heron. Large birds can be excellent models, particularly if they remain fairly still. In both of these studies, linear hatching is employed in the shadows. Alan also uses his fingers to smudge the pencil, representing another tone with different properties.

Interpreting photographs

If you want to use photographs I would advocate you spend much time studying from life also – photographs will then have added meaning to them and you will understand the printed image better. You will start to see around the subject, recognizing that the form of the bird continues around the invisible side; you will understand that the edges of the bird are just changes in plane and reflect light differently. Without this insight your bird will look like a cut-out, superimposed on your chosen background. However, in this specific case (that is, a tutorial in a book), when illustrating how to select lines to define shape, form and structure of a bird, there really is no alternative to using photographs – unless each copy of this book is to be shipped with a caged bird!

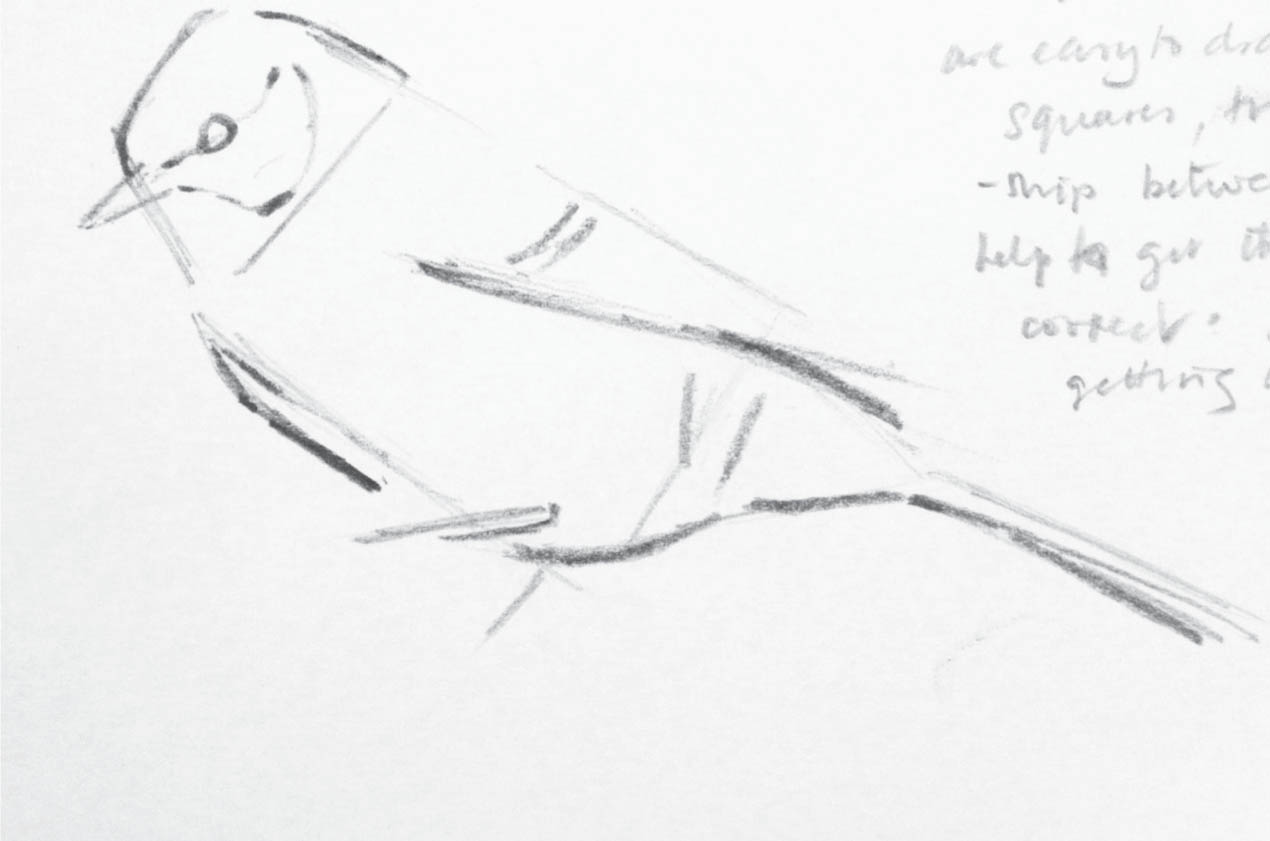

Look at the photograph of a small bird (a coal tit, found throughout Europe; there are similar species in North America called chickadees) and decide which lines could be simplified into curves and straights. Also pay close attention to the salient intersections and angles. By breaking down the major structures into these simple lines and shapes, notice how few lines can be used to draw the bird.

Because of the arrangement of feathers on the body, it can be difficult to ascertain just how the important bits of anatomy fit together and it is tempting to try to draw these elements first. Getting the general overall shape ought to be the priority; the elements of detail can be gradually added.

Tim Wootton: coal tit.

IDENTIFYING AND DRAWING SHAPES WITHIN A BIRD

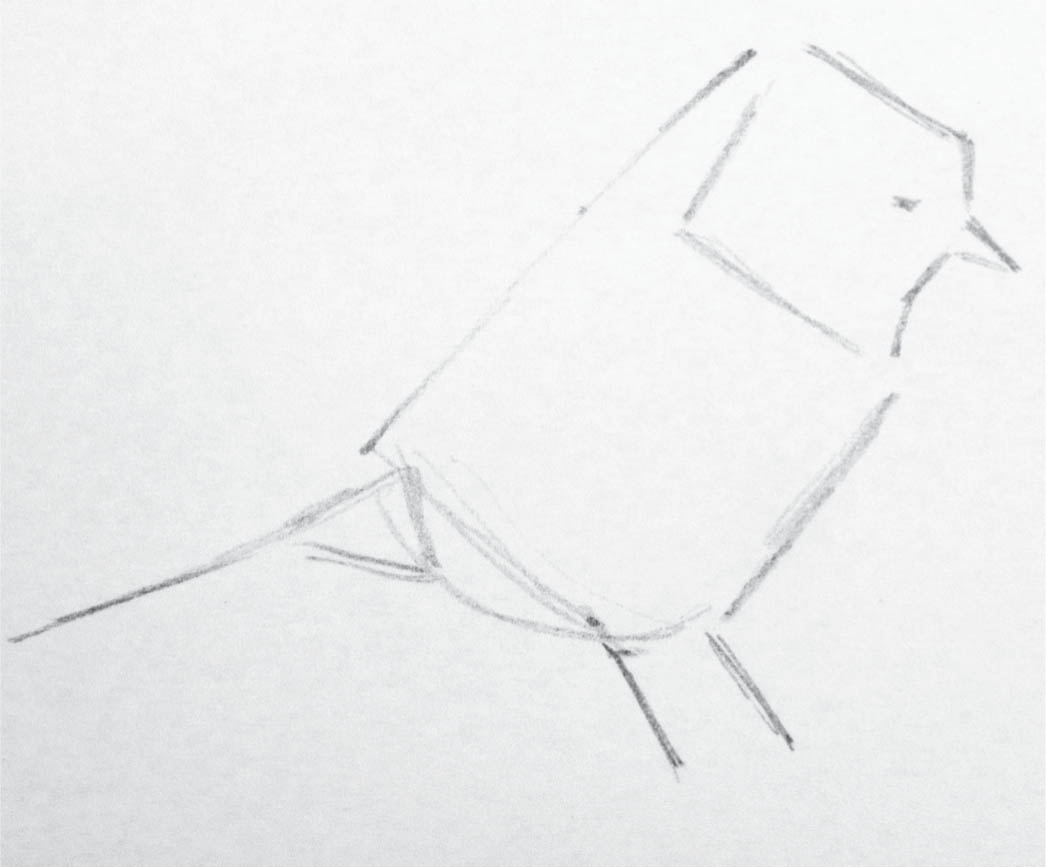

We are all familiar with the two-circle approach to drawing birds – a large circle for the body and a smaller one for the head. However, in many cases this basic anatomy can be replaced by a different kind of geometry. Squares and triangles can depict form with a sensitivity that may be quite unforeseen (and at a later stage, cubes and cones can be substituted to enhance three-dimensional qualities).

First spend a little time observing your subject, paying attention to the relative proportions of head and body. Look for strong lines where the bird’s plumage changes in colour, value or texture (different feather types) such as collars and moustache lines and how these may relate to underlying anatomical features. With many birds the feathers around the neck show a distinct line when the bird’s head turns. Observe where this line of separation is and mark it on your drawing – it can be an important feature when you come to expressing the character of the bird.

A point about these drawings: you may notice that the white cheek of the great tit has a dark line running across it, yet I haven’t included that feature in the sketch. We’ve discussed two points: one is to look at your subject in real life; the other is the aspect of interpreting photographs. In real life a great tit doesn’t have this stripe across the cheek – watching the birds will tell you this, and by interpreting the photograph I can see that the stripe is actually a shadow of a branch. It makes the bird look unusual, so I’ve deliberately left it out of the sketch.

When you start to put down a few lines try to visualize the point of balance of the bird. Legs needn’t be detailed, but a suggestion of where they emerge from the soft belly feathers and at what point they connect with earth or branch will help your drawing to stand properly – a very important aspect to your drawing and essential for making convincing studies.

Adrian Dancy: photograph of a great tit.

Tim Wootton: drawings of the great tit.

At this point it’s worth having some idea about the internal structures of the bird. The sketch below shows the position and shape of the legs underneath the feathers and where they attach at the pelvis (more of which in the next chapter).

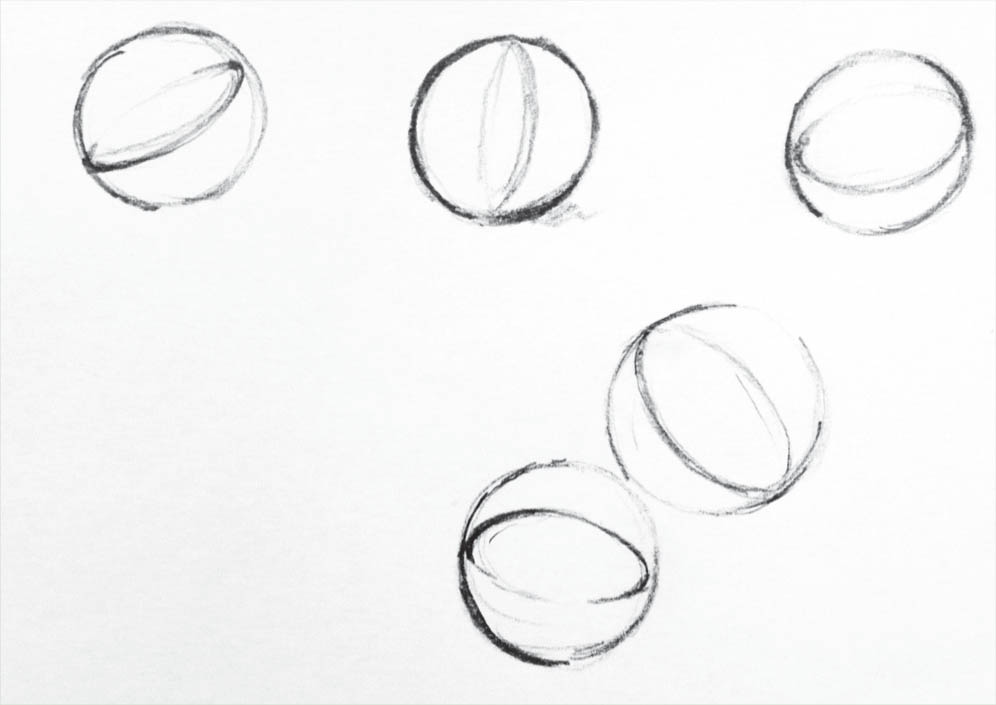

EXERCISE: DRAWING THE CENTRE LINE OF A SPHERE

One way to get the feel of balance is by drawing a series of spheres and then deciding where a centre line where both hemispheres are joined (the seam or equator). Sketch the ‘visible’ side of the seam as it curves around the ball. Imagine the spheres are transparent and continue the ellipse around the back of the ball. Try drawing the seam at different angles and from a range of perspectives. Visualizing the centre line of a ball is a step towards seeing and drawing objects in three dimensions.

Centre lines of spheres.

This drawing shows the centre line of birds as seen from a variety of angles. Sometimes in real life this is actually apparent on the bird’s breast. Being able to imagine this line will help you to draw the rounded form of the bird.

Centre lines of birds: robin, arctic skua, mallard.

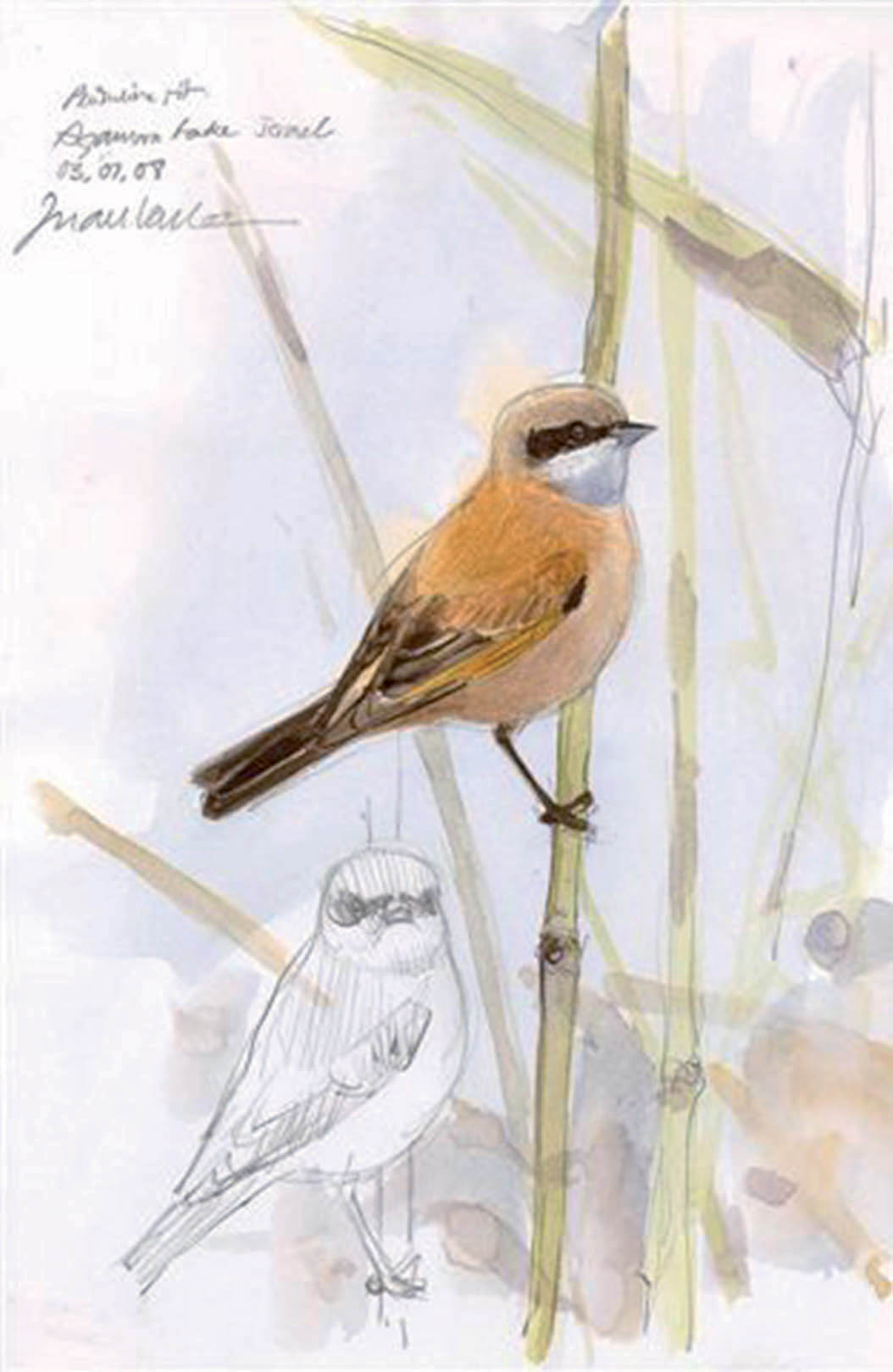

Juan Varela: penduline tit. Aspects of balance: in both drawings the ‘knee’ of the bird (which is actually the ankle) is visible; follow this angle and try to imagine where the true knee is and where then the legs would attach to the pelvis – remember the bird has two legs!

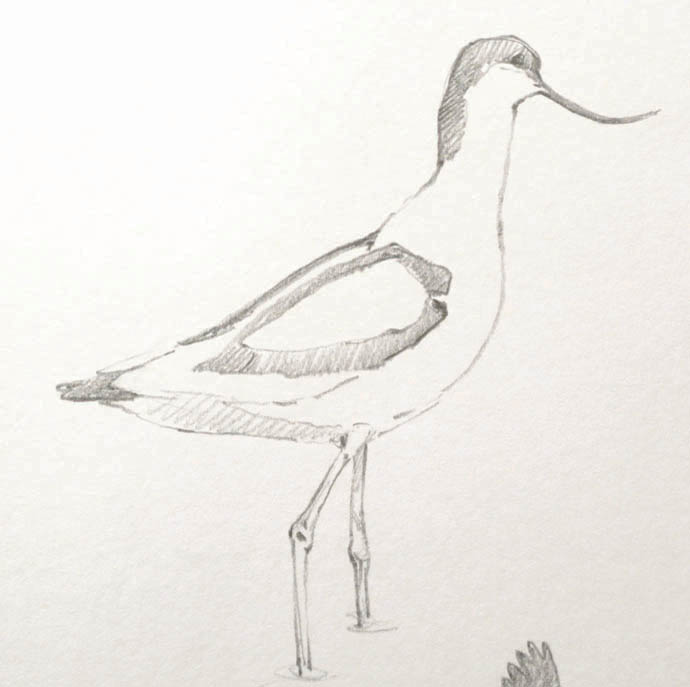

When drawing complex postures such as this three-quarter view of an avocet, (a three-quarter view is one where the subject is facing neither front-on, nor in side profile), look for the lines of most significance in helping convey the bird’s form and shape. In the case of the avocet, the ‘braces’ of black (which are actually black scapular feathers) are excellent guides for the artist; get these right and the whole drawing stands a good chance of succeeding. In addition to the braces, there is a second pair of black bands formed by the greater wing coverts and primary feathers being black. When the wing is in the closed, folded position, these two black bands form a teardrop shape, enclosing an area of white (see below).

The final picture shows the feather groups with the wings extended.

Tim Wootton: avocet.

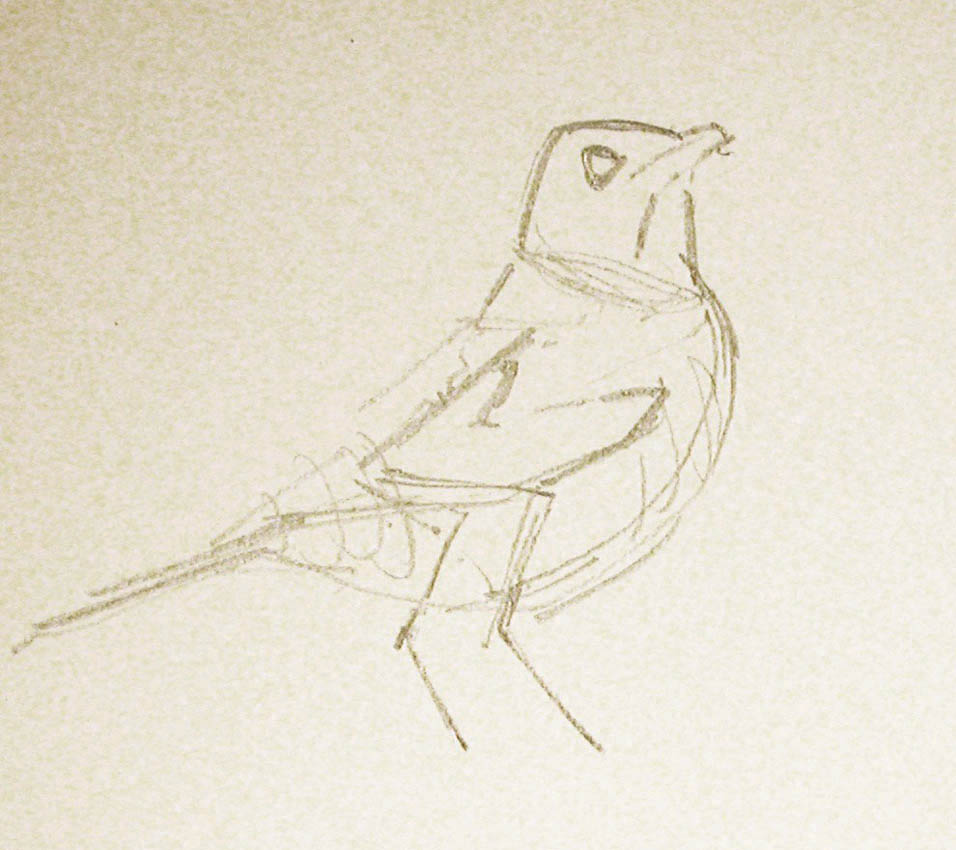

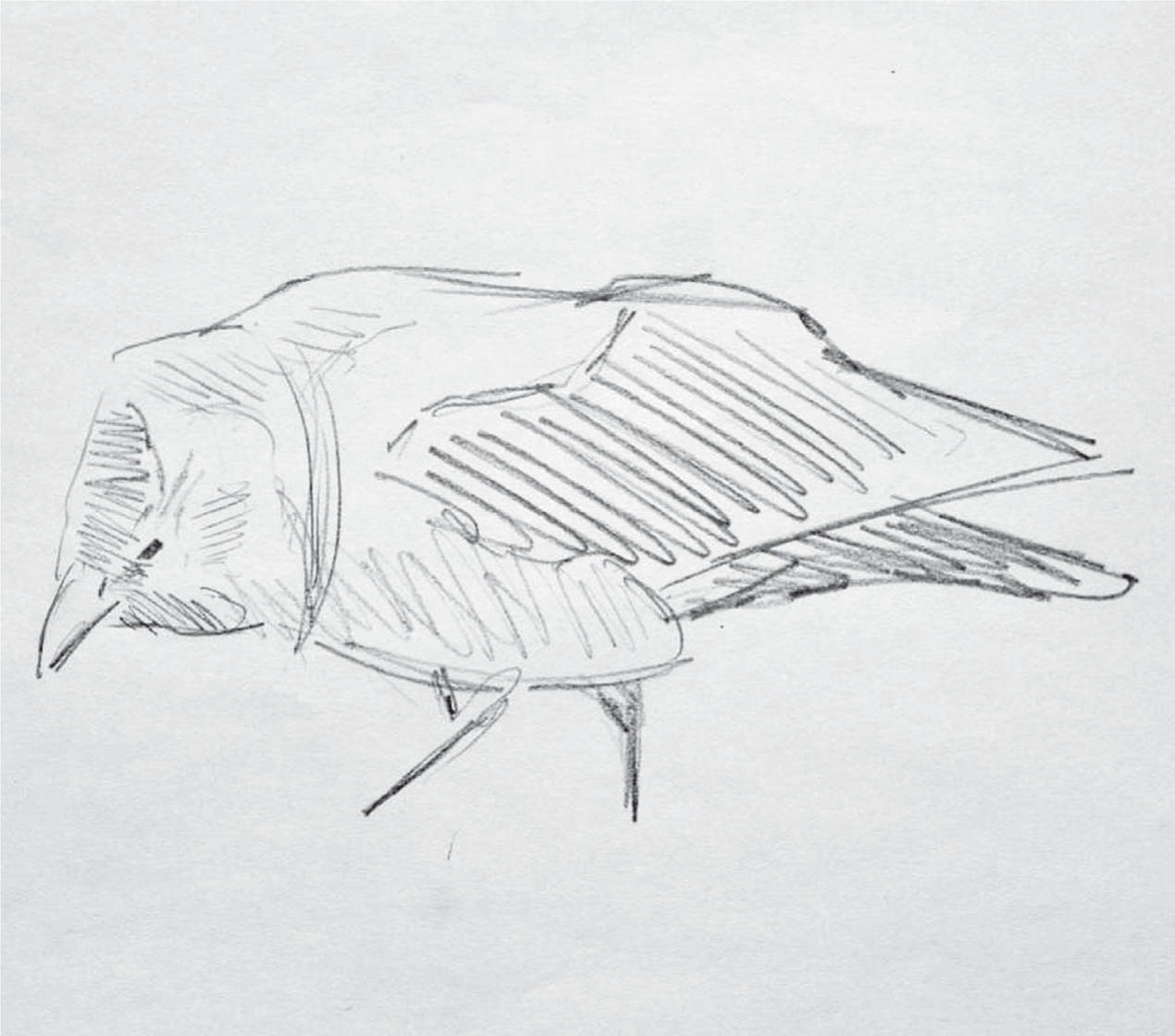

Tim Wootton: sketches of European blackbird, looking for lines of geometry.

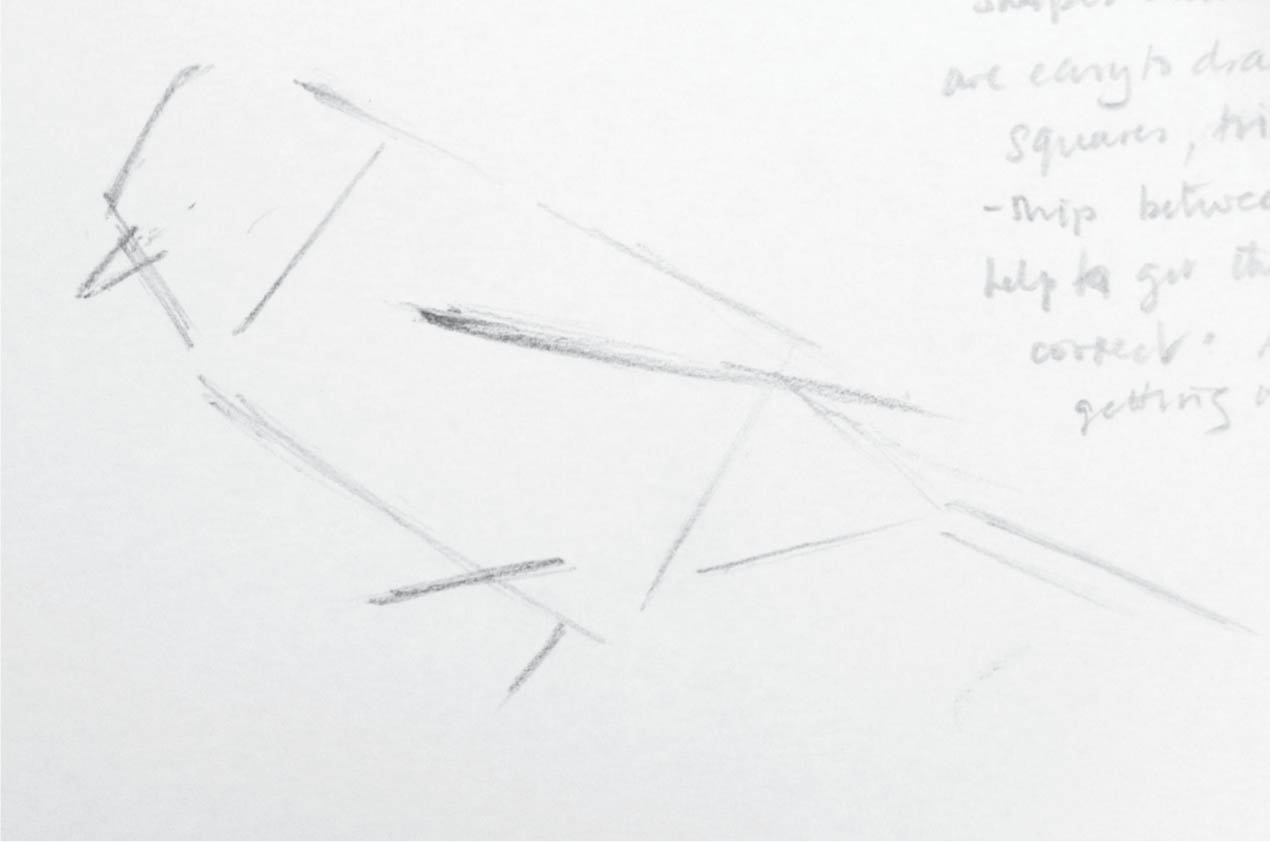

The two-circle approach is relinquished in favour of the use of more diagnostic lines and angles (note the use of construction lines, which also help to describe the roundness of the form). The legs are described as imagined lines through the body and connect at the pelvis. The head is drawn as a box, the body is based on an oval and the conical base of the tail is derived from a triangular shape.

If line is the fundamental method of drawing, then tone (shade), besides being a close associate, is also an essential process in its own right. Using tone only can be an exciting and descriptive way of drawing; the outline of the bird is suggested in the periphery of the tonal marks – a technique that has much in common with painting. This style is sometimes referred to as ‘drawing from inside the form’ and dispenses with an outline containing the structure. It is an effective way of drawing light – albeit in relief.

Tim Wootton: shelduck studies, using mainly tone to represent form and light.

Sketching using tone could be termed as drawing from the inside of the form. When we work in this way we are trying to mould the structure of the bird using light and shade.

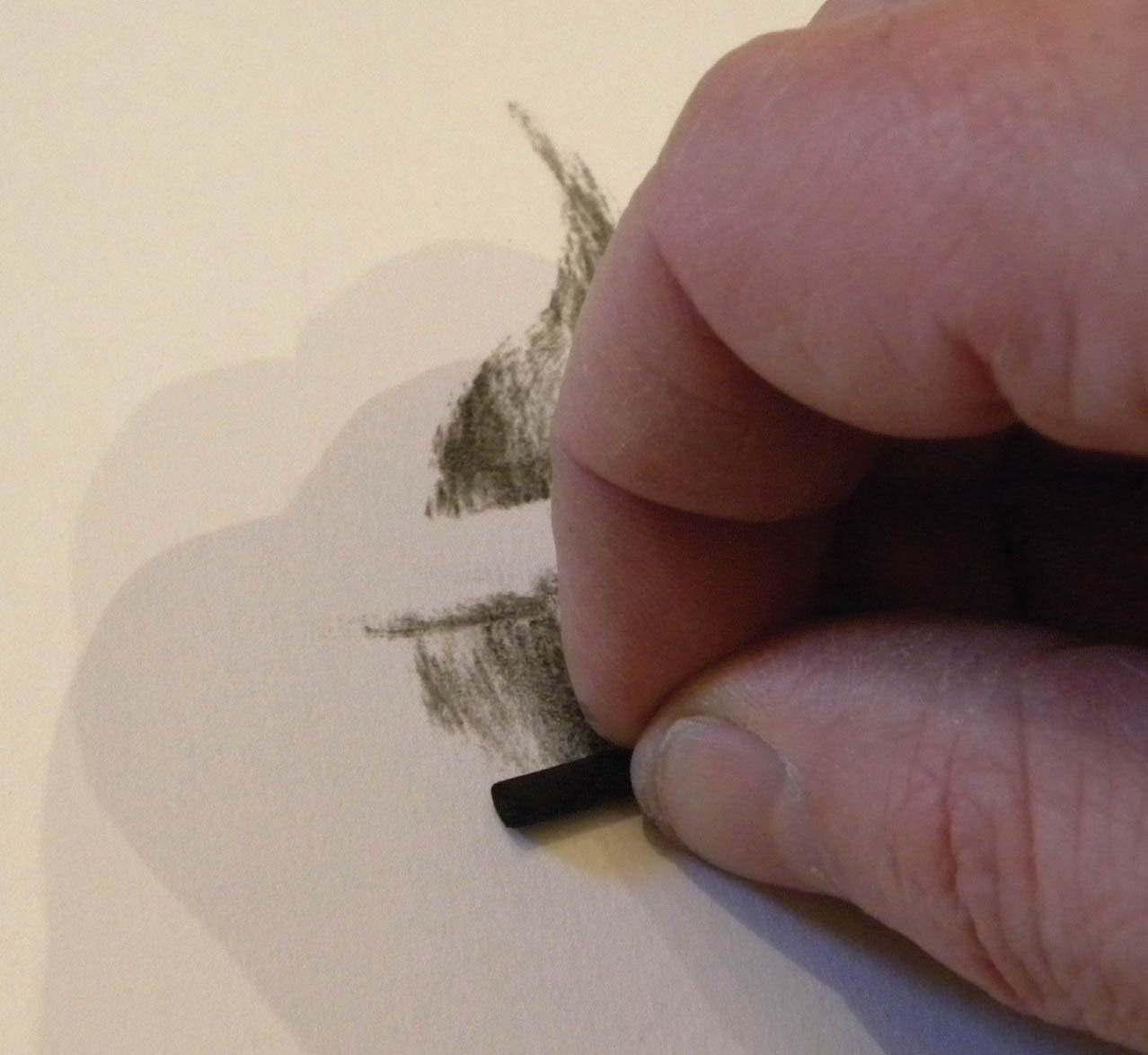

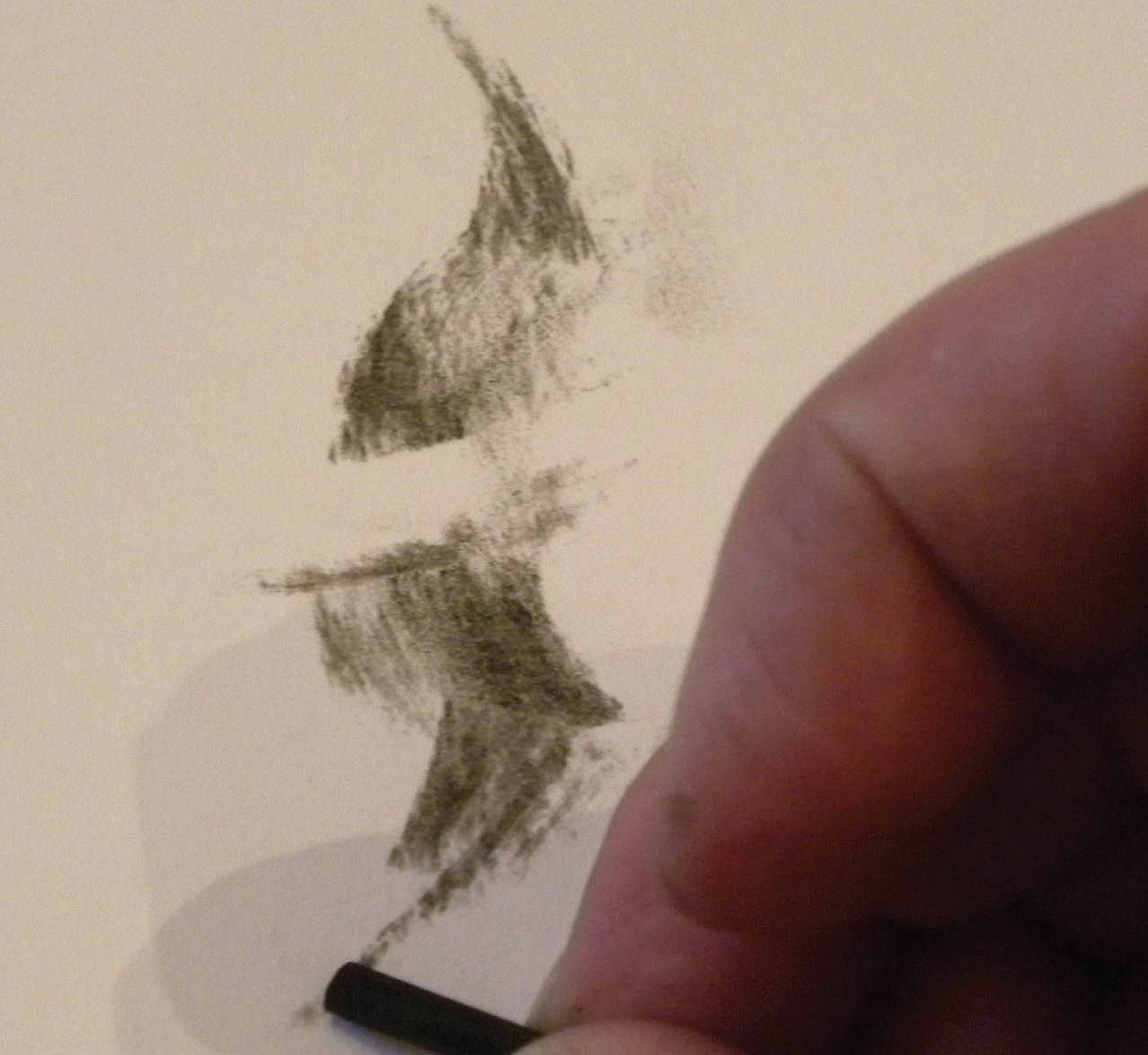

It may be useful to learn a few shorthand methods of making bird shapes, as practising them will bring more confidence with the media and the subject. The following examples use the sides as well as the point of the pencil and a couple of techniques are shown using charcoal (sides and ends).

Arctic skua in six strokes. Using the broad side of the lead make an arc, then, still using the pencil sides, bring the wings back into a point and finally a stretched oval with a rear extension and a dark smudge for a cap.

Arctic skua in charcoal. Using the side of a small piece of charcoal (about 1cm long) make an upward and gently concave sweep; stop, but keep the charcoal on the paper, then bring the mark back and to a point. Bring the stick to where you imagine the bird’s belly to be and make an upward mark, easing the pressure as you go. Use the end to sketch a dark cap and fine bill, bringing the line back and under the throat slightly. Finally a dark triangle and extended line are drawn for the tail. The simple shapes and varied tones are unconnected by outline, yet the eye assembles the pieces into a coherent and understood figure.

Using the flat side of a short piece of charcoal, make a curve towards yourself and then reverse the action making the pointed wing tip. Drawing the bottom wing mirrors the action. Use the stick-end for a breastband and cap, and to draw the lower abdomen and tail. You can use exactly the same strokes to draw the bird as though seen from above but simply continue the dark across its back.

MATERIALS FOR SKETCHING

Pencil

Pencil is the primary draughting tool and is available in varying degrees of hardness/softness. (H is hard, B is black, or soft, and the numbers grade the pencil correspondingly.) Many artists use propelling (automatic) pencils; these remove the need to sharpen as the lead is continuous, but the lines can be a tad uniform. I draw using a 6B (soft) pencil and I often alternate between line and tone in the same drawing, using the pencil edge to fill in areas of tone (this also has the effect of sharpening the pencil). Other handy monochrome media are available to the artist such as Conté pencils and pastels and charcoal pencils and sticks.

Alan Dalton: jackdaw study. Soft pencil and strong directional marks.

John Busby: Gannets on the Bass Rock. Conté drawing in situ. The process of mark-making is elemental in the artist’s work and it is instructive to follow the way he makes lines come alive. At intervals he pauses to reassess the scene before him and restarts the drawing making slightly darker statements as the pencil pauses on the paper. Important changes in direction of form are accentuated giving the drawing a strong sense of depth.

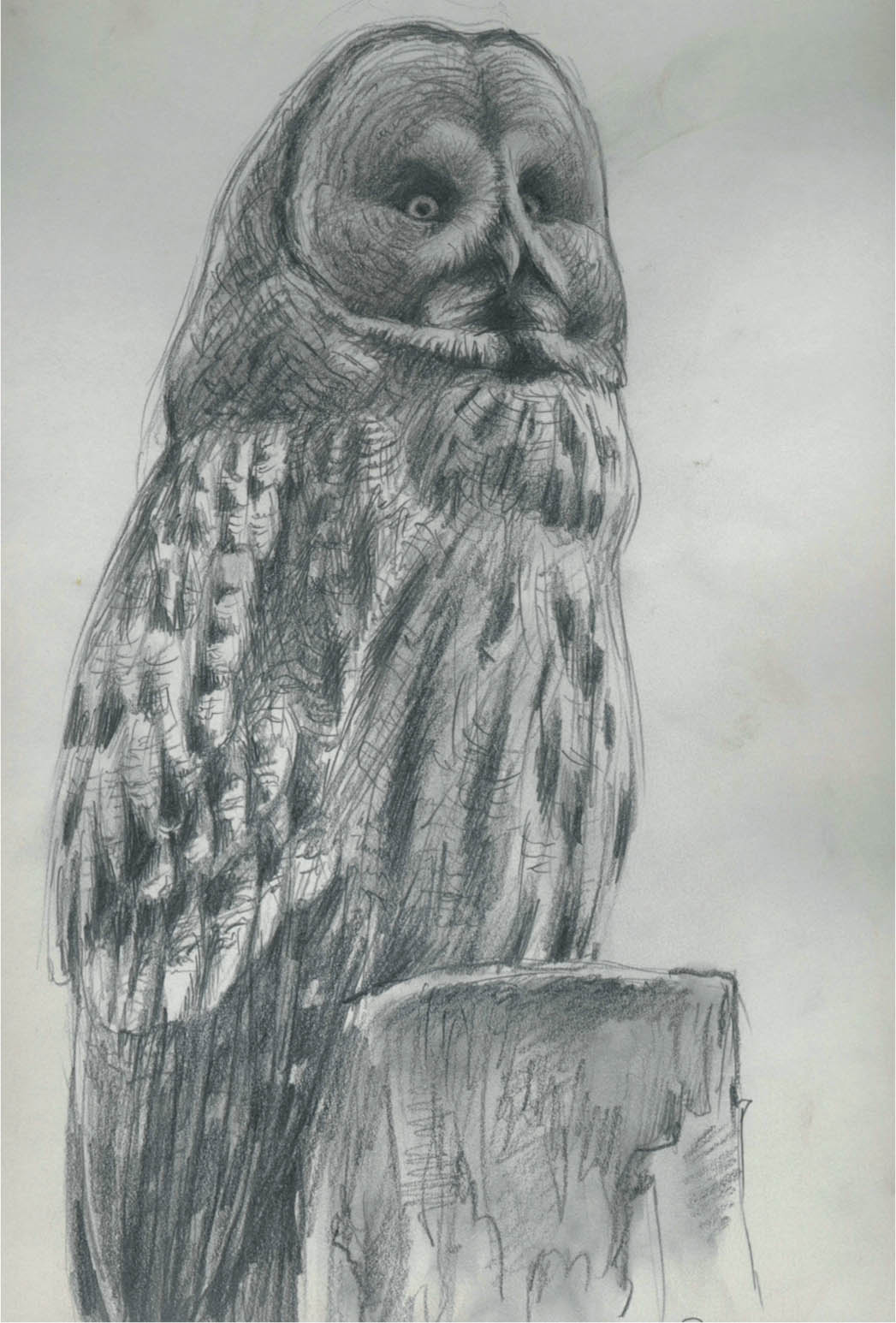

Paschalis Dougalis: Great Grey Owl. Graphite pencil drawing made from a captive bird. The artist investigates form and texture using all the variety the medium has to offer: line and tone, hatching and rubbing with fingers to make softer areas of tone. The drawing has a very wide range of values from blacks to areas of virgin paper as highlights.

Clive Meredith: Saker Falcon. Intensely detailed drawing derived from various photographs the artist made from a captive bird. Clive uses an ingenious method for the very fine white feathers. He scores into the paper with a fine, blunt tool which precisely delineates where he wants the highlights to remain. When he then uses pencil over this scored area, the grooves in the paper remain pristine and unmarked – a technique akin to brass-rubbing.

Tim Wootton: eider. Studio study from rough drawings made in the field – layers of tone are built up over the water areas, and the drawing of the eider is allowed to blend into the water, especially where the wings are moving fastest. Highlights on the bird and the splashes behind it are untouched paper showing through. The drawing is made on heavyweight household lining wallpaper (32” x 22”).

Tim Wootton: Intermediate Phase Arctic Skua, Fair Isle. A studio charcoal drawing using a selection of reference photographs of the seascape and drawings of arctic skuas made in the field. There is the additional use of white soft pastel along the backwash of the swell and in the turbulent water in the fore. Compositionally there are several points of interest, the skua being the foremost, then, following the direction of the bird’s flight, the swell of water takes the eye up and across. Afterwards the fissures in the rock lead towards the graphically represented arctic terns (the skua’s quarry); the natural exploration of the scene then follows the backwash from the rocks, into and past the dark cave and towards the intriguing hole – a sea-arch. The invitation is to suppose what may be beyond.

Alan Dalton: drawings of ruff (biro). The biro pen is a simple and handy tool that lends itself to making strong images. See how the major shapes of the feather masses are described and outlined, giving solidity to the drawing.

Ink

Ink is an excellent discipline to learn: it is immediate and cannot be corrected – once a line is made, it stays. However, this also gives the artist much freedom that pencil sometimes doesn’t – all temptation to rub out is taken away and you can concentrate on making the drawing.

Ed Keeble: spotted crake wing-stretching. A moment captured immediately in this tiny biro drawing.

Ed Keeble: peregrine. The artist gets straight onto the important lines; form and structure are suggested by quick marks describing the planes contained with very definite and accurate profiles.

Drawing with wash is a hybrid technique sharing much in common with pure draughtsmanship and having the expressive freedom of watercolour. It is also a very quick way of working: the brush can be made to switch from making lines to filling areas of tone instantaneously. The technique removes the need for a preliminary underdrawing and allows you to express lights and shadows efficiently.

Tim Wootton: long-eared owl. During a session working in the field I alternated between pencil studies of this roosting bird, and watercolour work – using the drying time required for the painting to make pencil drawings. I used separate sheets of paper clipped onto a board – these could be removed and left to dry, leaving me unhindered to continue working.

Alan Dalton: juvenile starling. Wash sketch using raw umber as the hue. The bulk of the bird’s general colouration is first laid onto the paper leaving the secondary flight feathers clear. With the addition of high-contrast shadow lines in the wing, the glossy nature of this area is perfectly rendered. Darker tones along the breast and head are produced by a second application of the wash once dry enough.

Darren Woodhead: bullfinches. The ability to see form and capture movement intuitively is required to produce studies such as these. The introduction of colour makes a strong connection to real life.

FLIGHT

Perhaps the most obvious difference between most mammals and birds is the power of flight and it is this supremacy in the air that is possibly the single facet we covet most. It contributes to the sense of ethereality that tiny birds have, and can embody a suggestion of enormous power and dynamism. No one aspect of being symbolizes ‘the bird’ more than its ability to fly and no single feature of the bird is more difficult for the artist to capture and express. But it can be done.

As with all aspects of study, start with the most accessible and achievable goals; drawing birds in flight is all about confidence (backed up with a few basic principles). Study the anatomy of the bird you are aiming to portray; the respective lengths of wing bones and the general shape of the wing are vital details of character, which group birds of similarity together and can be so specific as to relate to a single species and no other. The method of flight is also diagnostic and ought to be observed and understood if the resulting drawings are to relate to the bird.

Juan Varela: booted eagle. (First published in Entre Mar y Tierra/Between Sea and Land, Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.)

Large birds such as eagles and hawks, storks and cranes, swans, geese and gulls show their wing shapes well in flight, soaring and gliding much and using relatively slow movements of the wing. Smaller birds that rely on speed for capturing prey (or avoiding becoming that prey) can use wing beats so rapid that the shape of the wings cannot be discerned with the naked eye. When depicting species that fall into this category, it is important for the artist to convey the suggestion of movement or else it is quite likely that the resulting work will have the effect of ‘freezing’ the bird in time and space. (Unless there is some specific creative or personal reason for doing it, this ought to be avoided.) There are techniques that the artist can deploy to convey the idea of this rapidity of movement; these are discussed in Chapter 6. To begin with, we will look at some birds that offer the opportunity to study wing shape and action whilst in flight. As mentioned above, the larger birds are the ones to focus on and, unless one has access to a captive bird of prey which can be watched on its exercise flights, we should look to common species. Geese and swans are conspicuous in flight, but tend to be ‘going somewhere’ and opportunities could be sparse (although strategically placing oneself at a well-used winter roost can present excellent prospects of watching geese alighting), whereas gulls are fairly ubiquitous and readily available to the artist. Besides the obvious haunts of the coast, harbours and islands, gulls are found in numbers at gravel pits, refuse tips and agricultural land as well as in many towns and cities.

Birdwatching and drawing from sea cliffs presents a variety of aspects of view. Besides the usual angles as the birds fly overhead, eye-to-eye and views from above give a real sense of sharing the air with them. In the breeding season the birds will be everywhere and there is apparent chaos; however, if you spend a little time watching it will soon become clear that certain patterns emerge. Birds will take similar courses along the cliff face, regularly repeating shapes and poses as they do so. Recognizing these patterns is very helpful to the artist and anticipating the next beat in the rhythm will have you prepared to see the desired shapes and lines, and to get them down on paper.

When drawing birds in flight I find it helpful to try to imagine I’m flying; that is, I hold my arms outstretched as a gull’s wings might be, angle my wrists and elbows and see if I can ‘feel’ the air lifting me. It may look a little strange, but I can assure you it helps to get in the right mental state, to start to understand how it might feel were I able to glide on the air. Watch how the birds change the shape of their wings, offering different angles and alternate planes of their wings to compensate for and utilize best any changes in wind strength and direction as it eddies around the cliffs. Observe the twist and slant of the tail in its role as rudder.

When starting out on a drawing session, look to the simple and obvious lines which describe the bird and the direction it is moving, and draw the bird’s spine along that axis. Wings can be quickly suggested by a simple ‘W’ shape – make many gestural drawings just as fast as the action happens, and be aware of the patterns in front of you. The simple lines can be added to as birds resume similar attitudes during the session.

Tim Wootton: angles and momentum. Simple and immediate representations of seabirds in flight are made; secondly the wings and bodies are fleshed out by adding trailing edges; finally a wash of yellow ochre and blue places the drawings in the air.

Tim Wootton: wing perspective in flying birds. I have marked the ‘exit point’ with two dots of the wings on the two gulls in flight at the top of the page; note they are opposite each other, on the same perspective as the body – there’s also a very geometric peregrine up there somewhere. Arctic skuas and a fulmar, and an arctic tern (bottom of the picture) emerging from a dive.

A photographic memory would be an advantage in this situation, but if you don’t have one, it may be possible to cultivate one. We are told to draw what we can see and this is pretty good advice. But, in the case of moving birds there is no time to check back to see if what we’ve drawn is ‘right’. Intuition and interpretation are skills we need to nurture. Watch the birds, check the wind direction and updraught – and select a species to study. Gannets and fulmars are superb models for the artist, partly because they are quite unafraid of us and partly because where they are found, they are found in plenty. At their breeding cliffs and with a stiff onshore breeze, it is possible to sit with birds above your head and virtually in front of your face just hanging in the air.

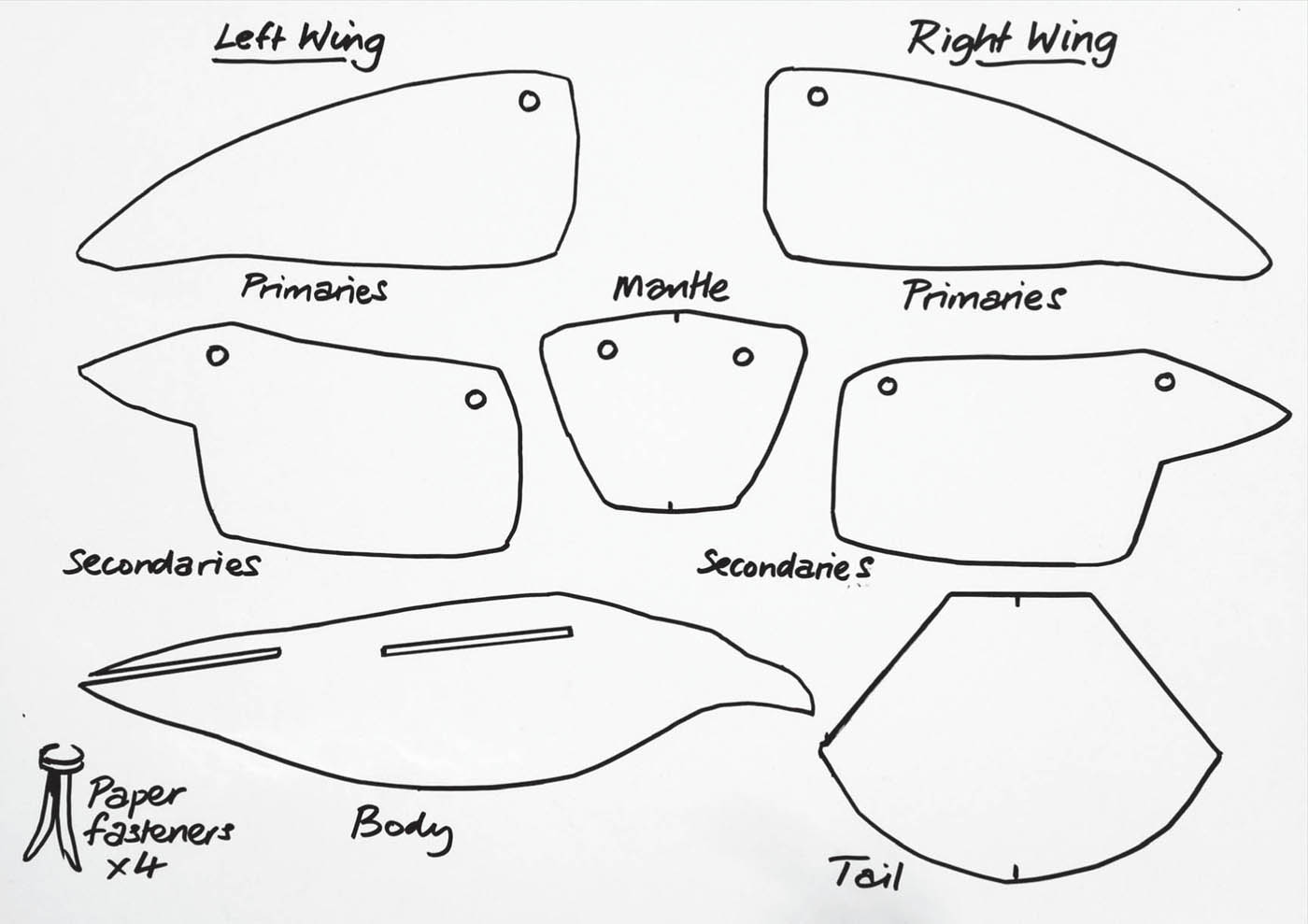

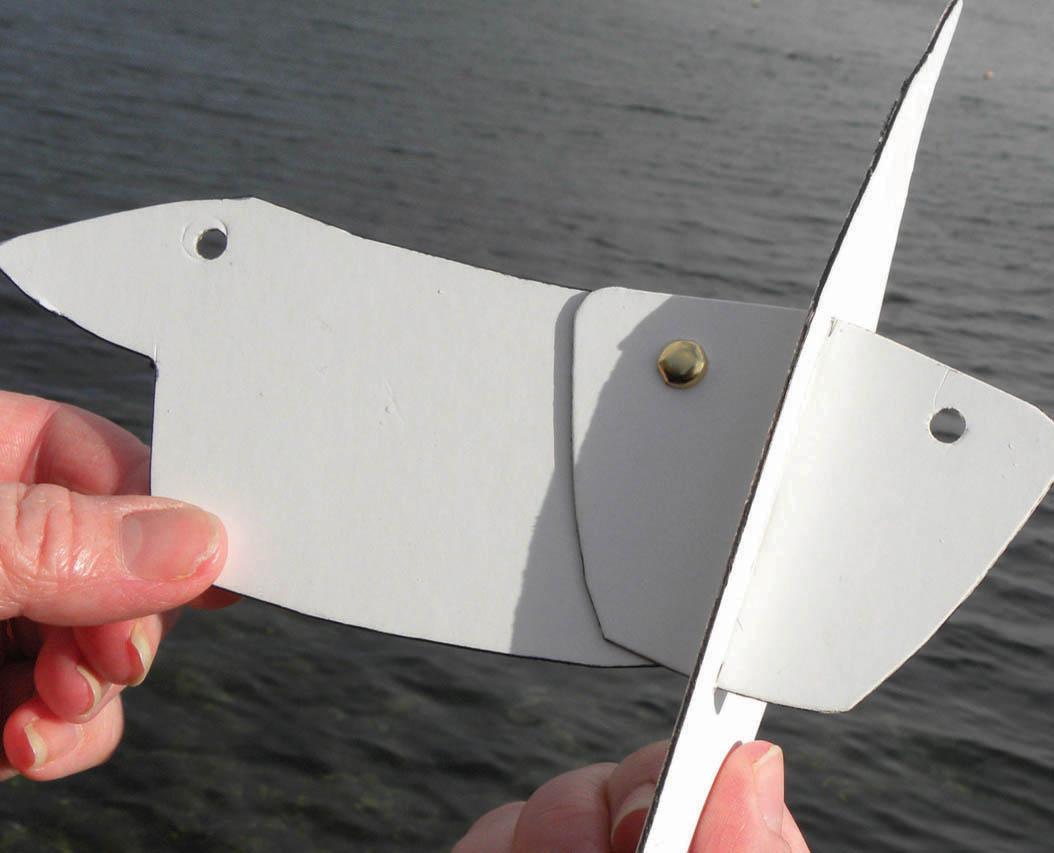

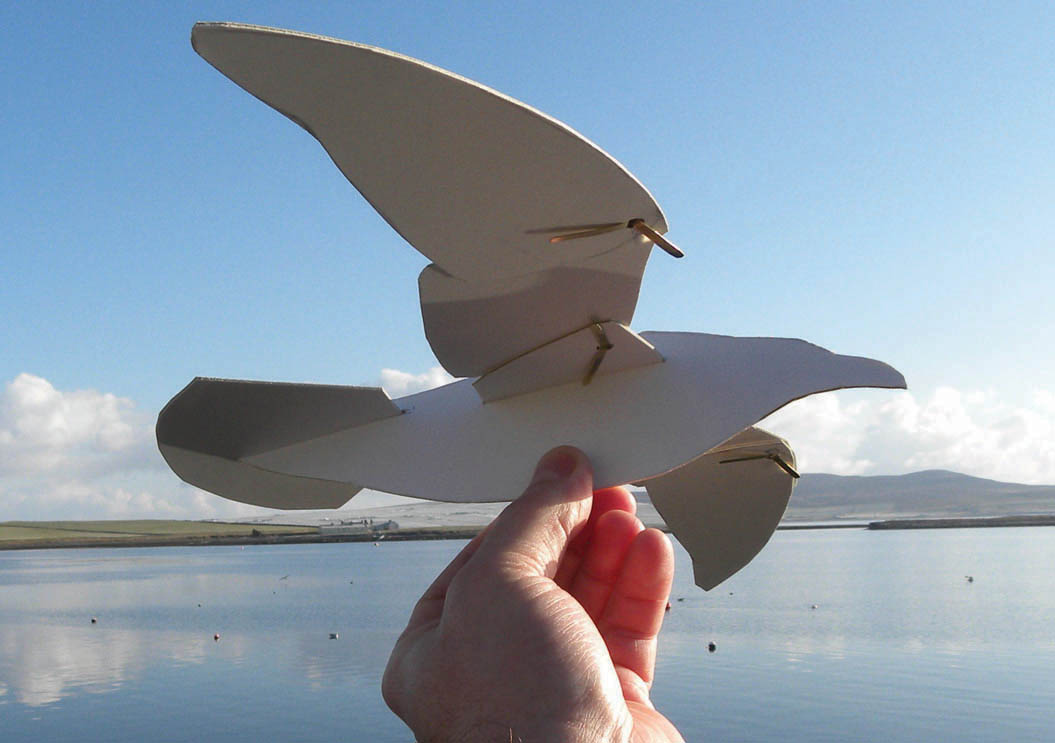

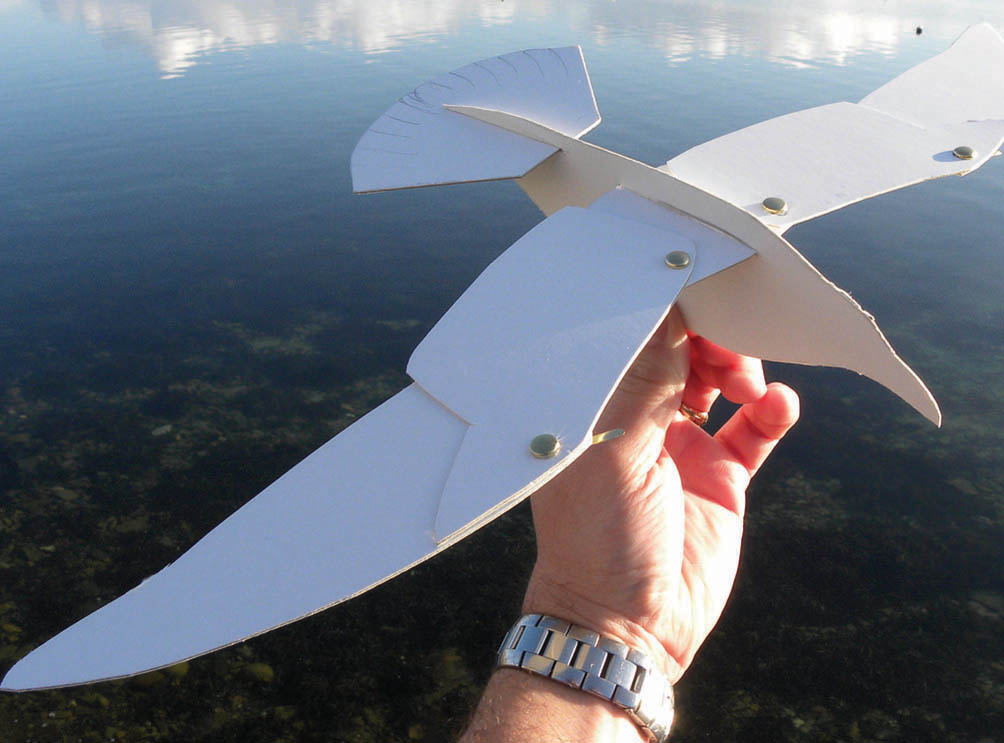

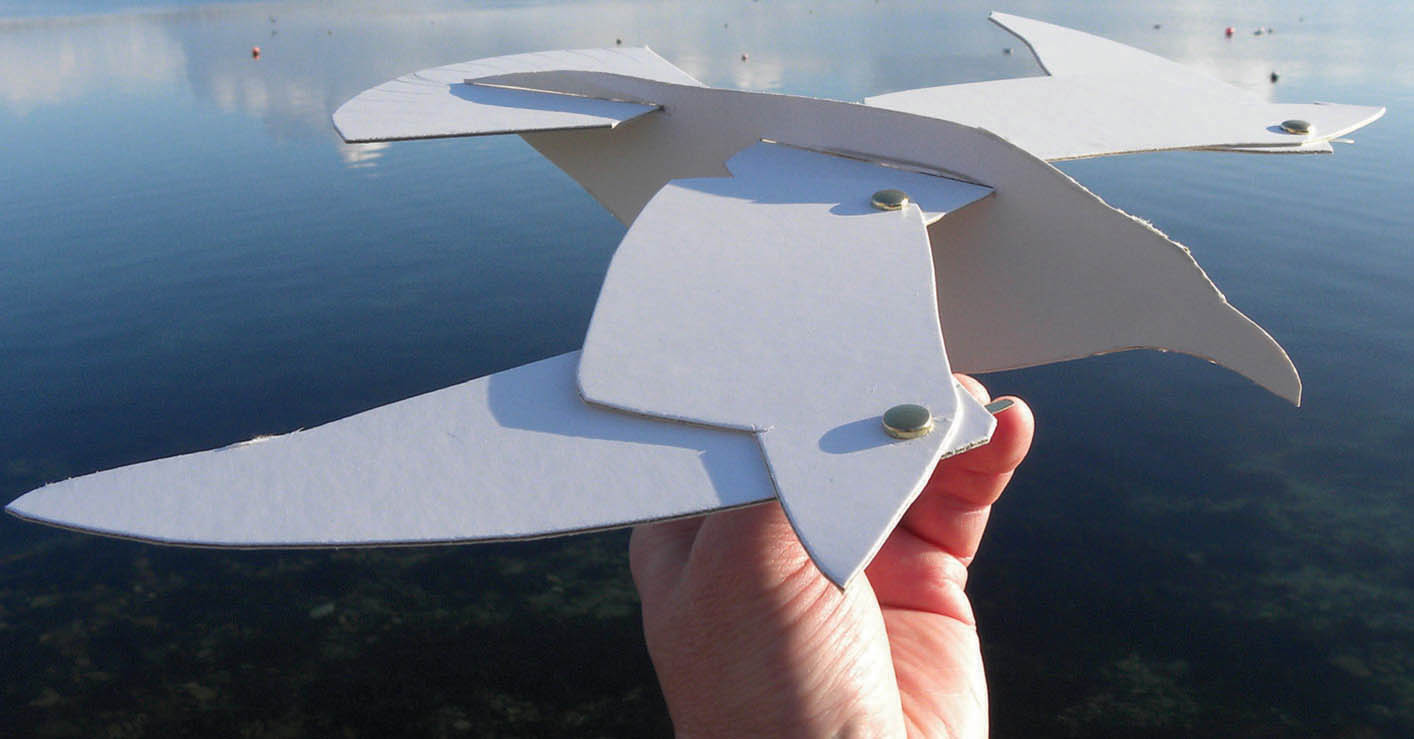

MAKING AN ARTICULATED MODEL GULL

Enlarge this sheet to A3 and trace onto thin card. Cut out the shapes and punch holes as indicated. Assembly is as illustrated below.

Template for an articulated gull.

a) Slide the mantle through the slot.

b) The secondaries are fastened to the mantle underside.

d) Attach the tail.

Wing shapes and perspectives.

The wings can be articulated more or less as in the real bird, offering a range of wing profiles. Turning the model in the air will help you to see the perspective of the wings (although being very close to you, this is much exaggerated and shouldn’t be taken as representative of birds seen from a distance). It also helps to see where light may hit a real bird.

This is where the first exercise we did can be applied to a real situation. As on the still life, select a bird that you can see well, take note of the angle of its wings in relation to its body, how deep its chest is and how far up the bird’s body the wings emerge and most importantly, try to visualize the negative space between the wings and the body (that is, try to describe to yourself whether there are acute triangles of light visible through the gaps, etc.). Once you feel you can ‘see’ the bird, take a snap-shot – in other words, snap your eyes closed and try to remember the shapes you could see and draw them immediately from memory. Stop drawing when you can’t remember certain features, shapes, proportions and so on. Take your drawing and compare it to the bird the next time it’s in a similar position – check proportions and angles. Soon you’ll be able to see where the errors in the drawing are and you can correct them using the living bird as reference. The more you practise, the more success you will have when it comes to ‘seeing’ the moving bird.

Tim Wootton: fulmar flight studies.

A step on from the exercise illustrated above is to use the sides of the pencil as well as the point. You can draw both the leading and trailing edges of the wings with one stroke; a useful device for capturing aspects of composition when watching flying birds as you can get shapes down very quickly.

Birds in flight show feather masses and only the individual feathers that are very conspicuous may be discerned, such as the first four or five primary feathers on the wings of hawks, eagles and crows or specific tail feathers of some birds. The groups of feathers make sense when the bird is observed in flight.

A shorthand for a flying gull.

Tim Wootton: arctic skuas. Oil on canvas. When at the coast the atmosphere has real body to it – salt and moisture laden – the light is affected in curious ways. I wanted the physical aspect of the air to play a major role in the way the colours are perceived in this piece.

Bruce Pearson: black-tailed godwits display flight. Pencil and wash; keenly observed action all over the page.

Andrew Ellis: golden plover flock. Acrylic on panel. The viewpoint and perspective puts us right there, in amongst the flock of plover. The focus slips slightly as the birds get further away from us, a device that creates depth in the piece but also takes the attention away from the more distant birds, allowing us to engage those closest. The wing tips, being in motion, are painted slightly sketchily, forming the impression of action – the golden light echoes the species name.