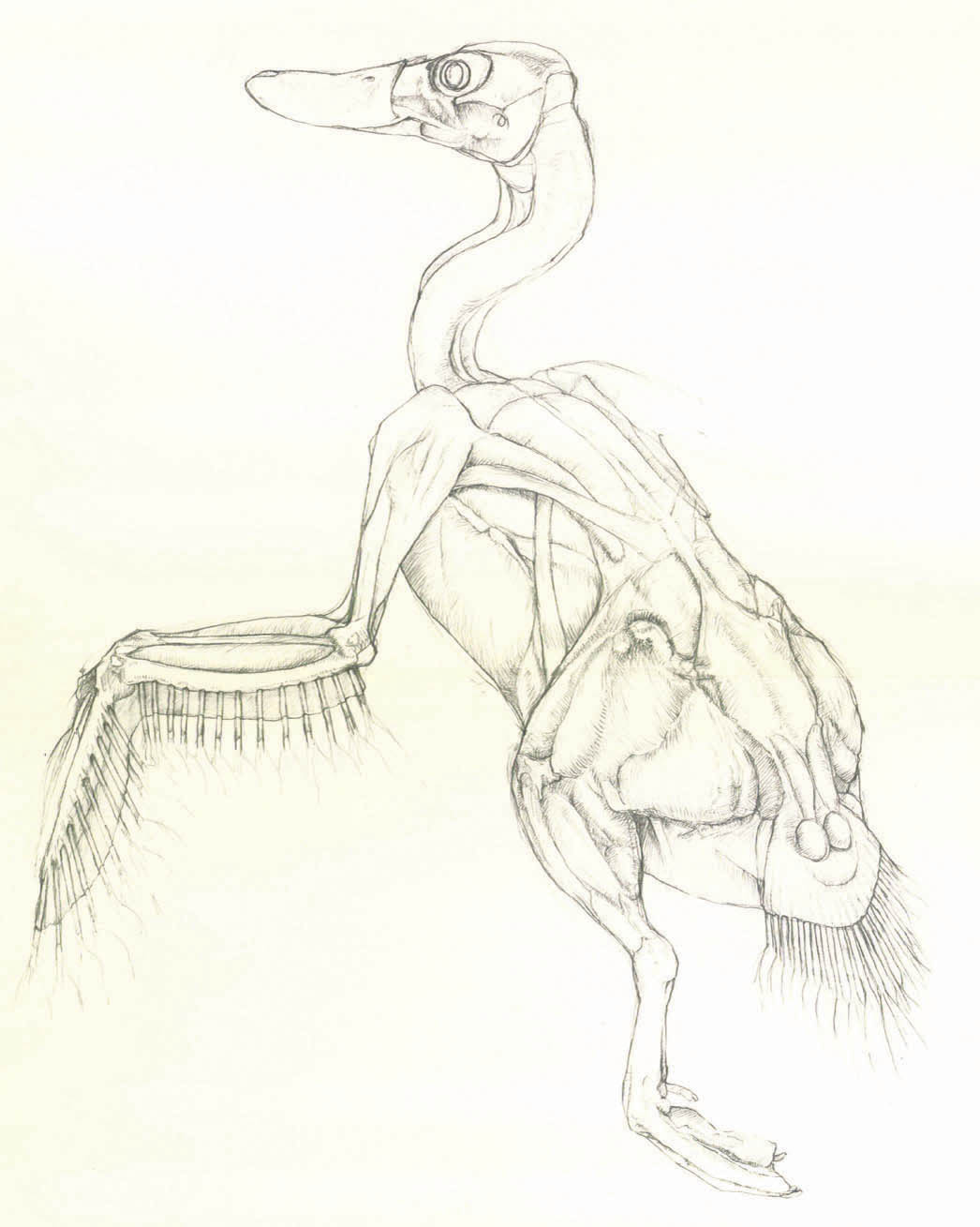

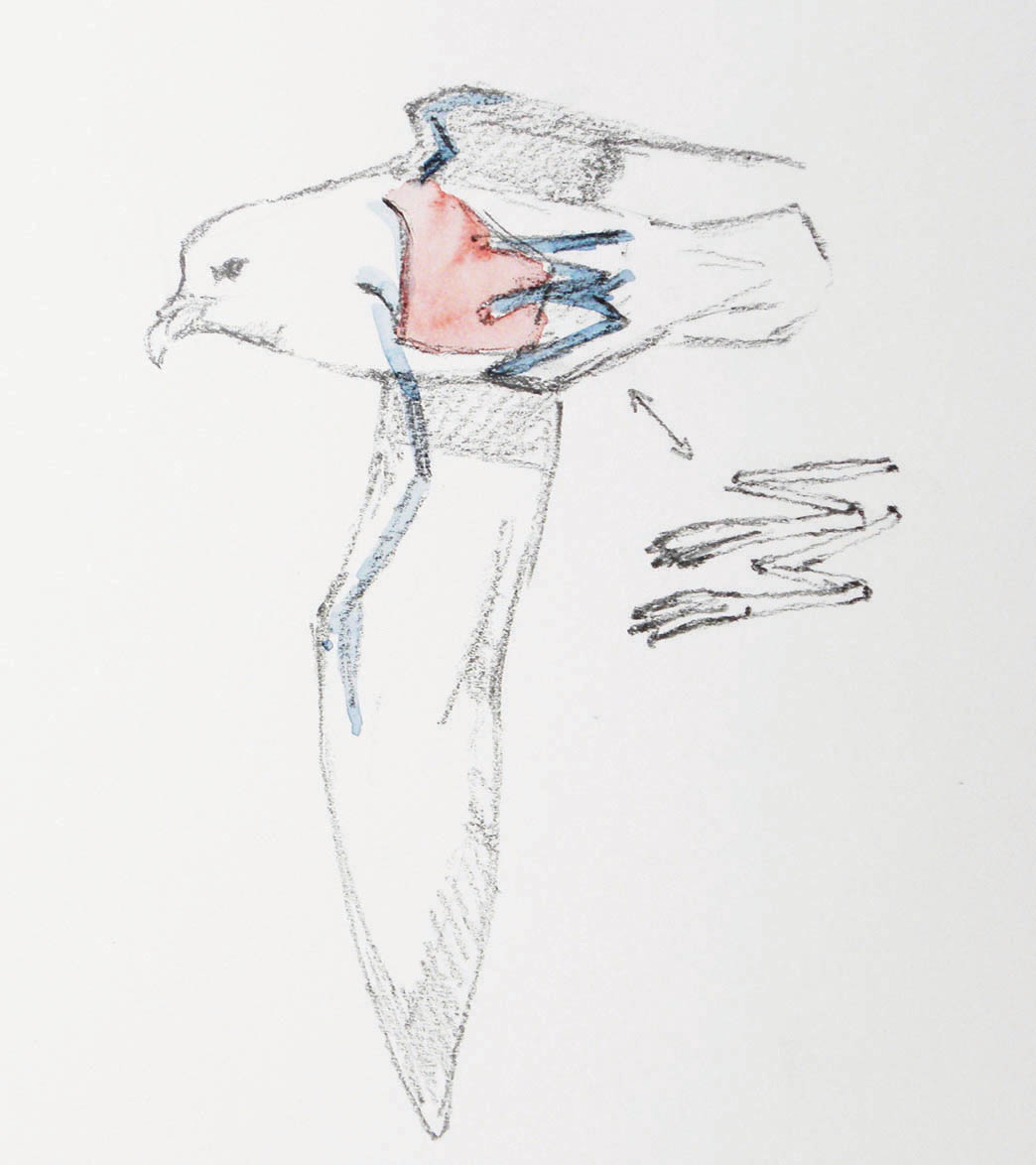

Tim Wootton: common gull post-mortem study.

ANATOMY

To suppose that the eye with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed by natural selection; seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest degree.

Charles Darwin

I wish I had eight pairs of hands, and another body to shoot the specimens.

John James Audubon

To understand how a bird stands and moves, it is important to get to know at least a little bit about the bird – from inside out, so to speak. In this section we will look at a range of different skeletal adaptations and how these adaptations affect the way the bird looks and moves. There is a huge variety of species and types in the world and a tremendous range of scale too. But birds (generally) share the ability to fly. This is the result of a unique morphology including distinctive skeletal construction, muscle development and feathers.

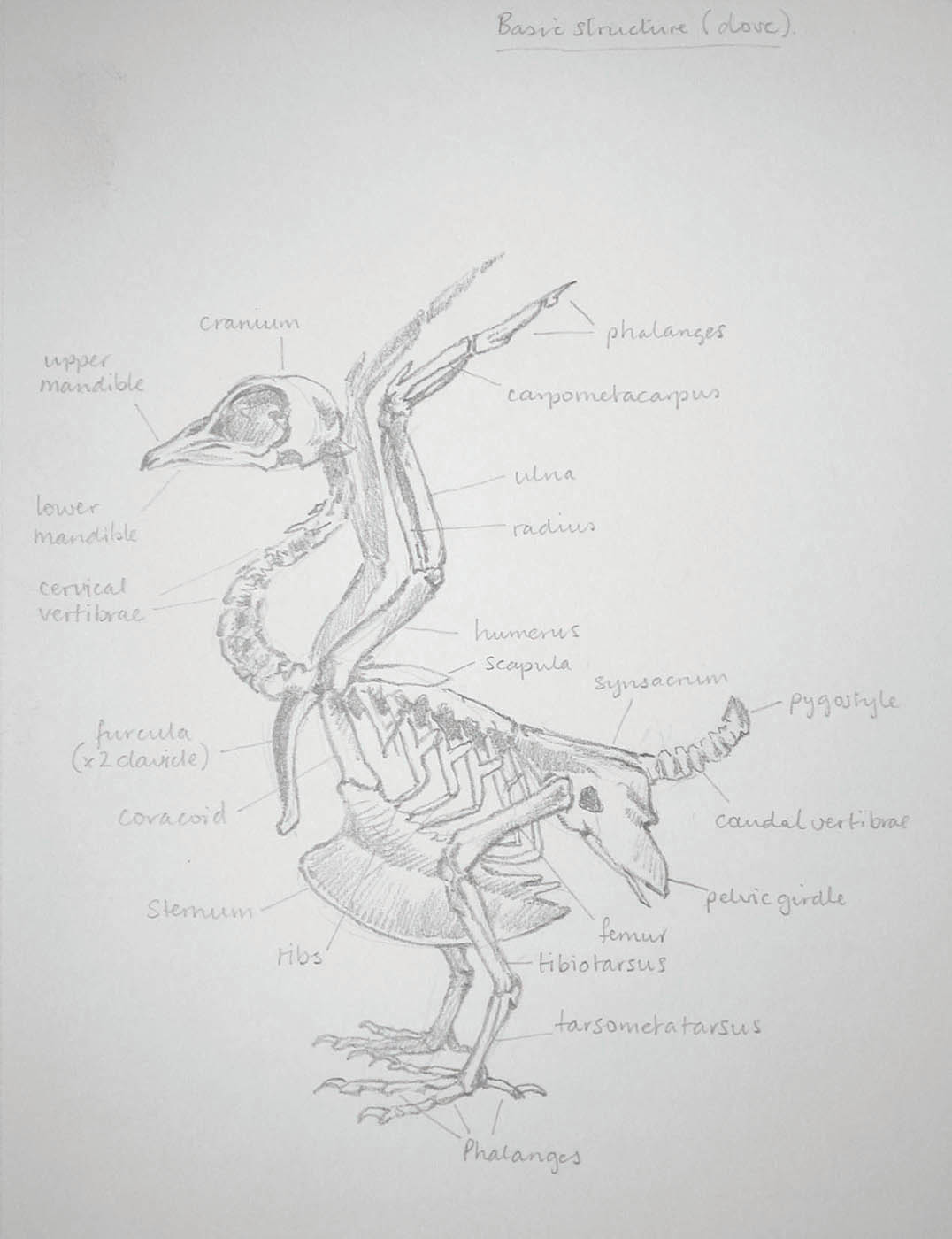

Birds have developed specifically and uniquely and their primary difference from all other animals is their ability to fly. Special adaptations include extremely lightweight bones. Generally these are hollow and are reinforced with an interior lattice-work, which increases their strength whilst adding very little to their overall weight.

Birds have proportionately large breast muscles which attach to a blade-like extension of the sternum – the keel or breastbone. This arrangement will be familiar to anyone who has carved a chicken at Sunday lunch. These large muscles, however, create great stresses on the skeleton during flight and further mitigating adaptations can be seen. Large sections of the vertebrae (backbone) are fused together for strength. This also means that most birds cannot flex their spines – an important feature when drawing the bird. The collarbones are fused to form the ‘wishbone’ and the ribs have lateral extensions that overlap the subsequent rib. These appendages are known as the uncinate processes and contribute to the overall strength of the thorax.

Basic avian skeleton – dove.

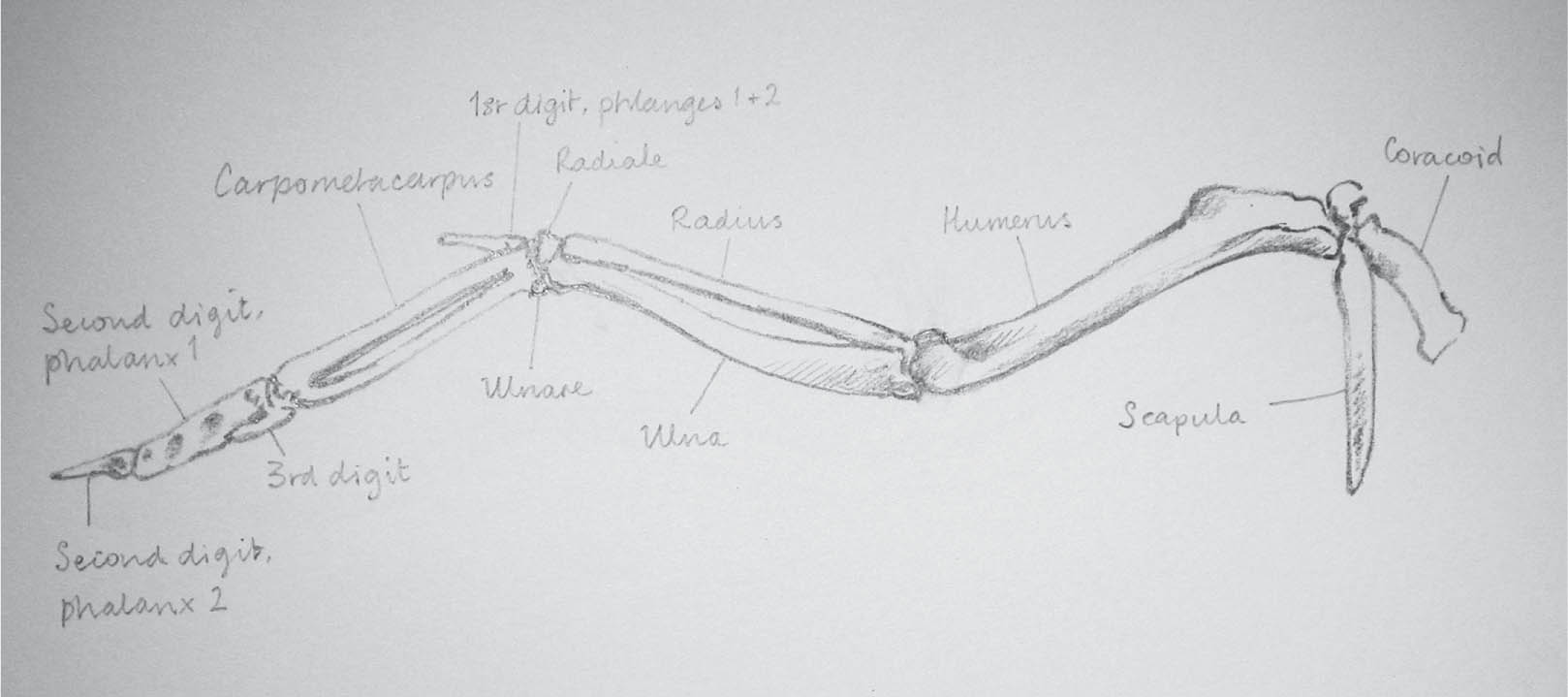

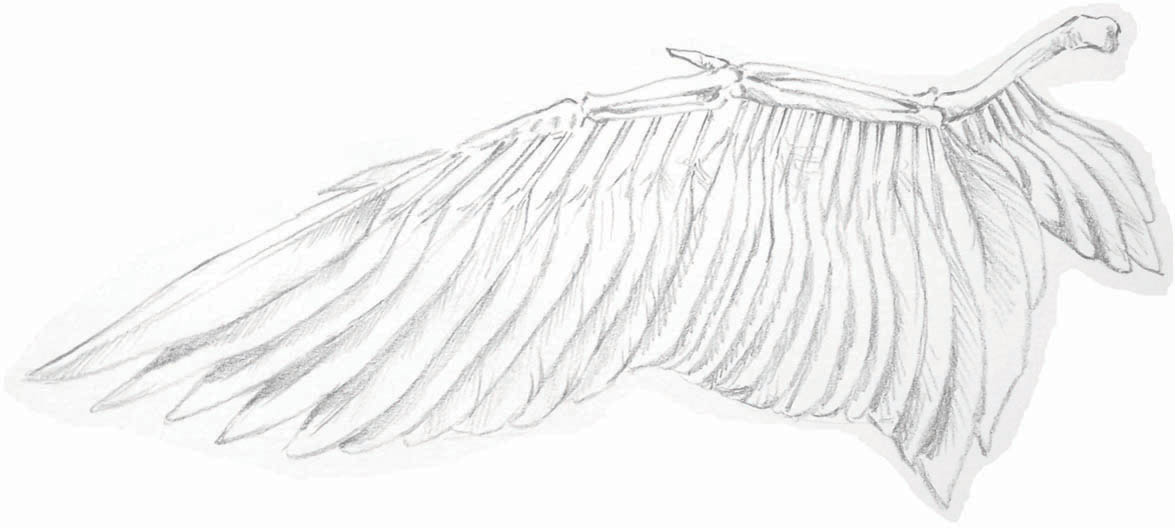

Perhaps the most complex joint structure in the bird’s skeleton is the wrist. It is capable of locking and releasing at given moments during the flapping action and articulates to enable something akin to a figure-of-eight movement. It assists in allowing the bird to perform the most intricate manoeuvres. Unsurprisingly, these bones are highly specialized, although there is a similarity to those of the human hand, even if assembled somewhat differently. As with the leg, the rest of the arm bones bare close similarity with mammal forelimb bones.

Typical bird-wing osteology…

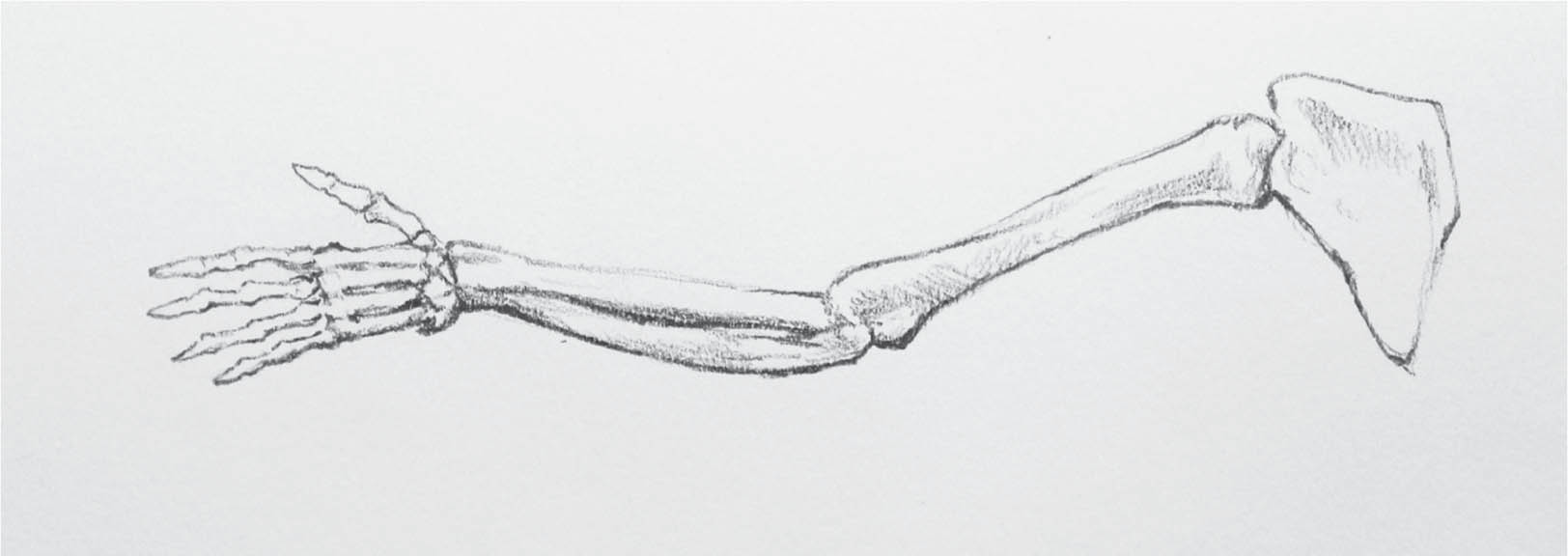

… compared to the human arm.

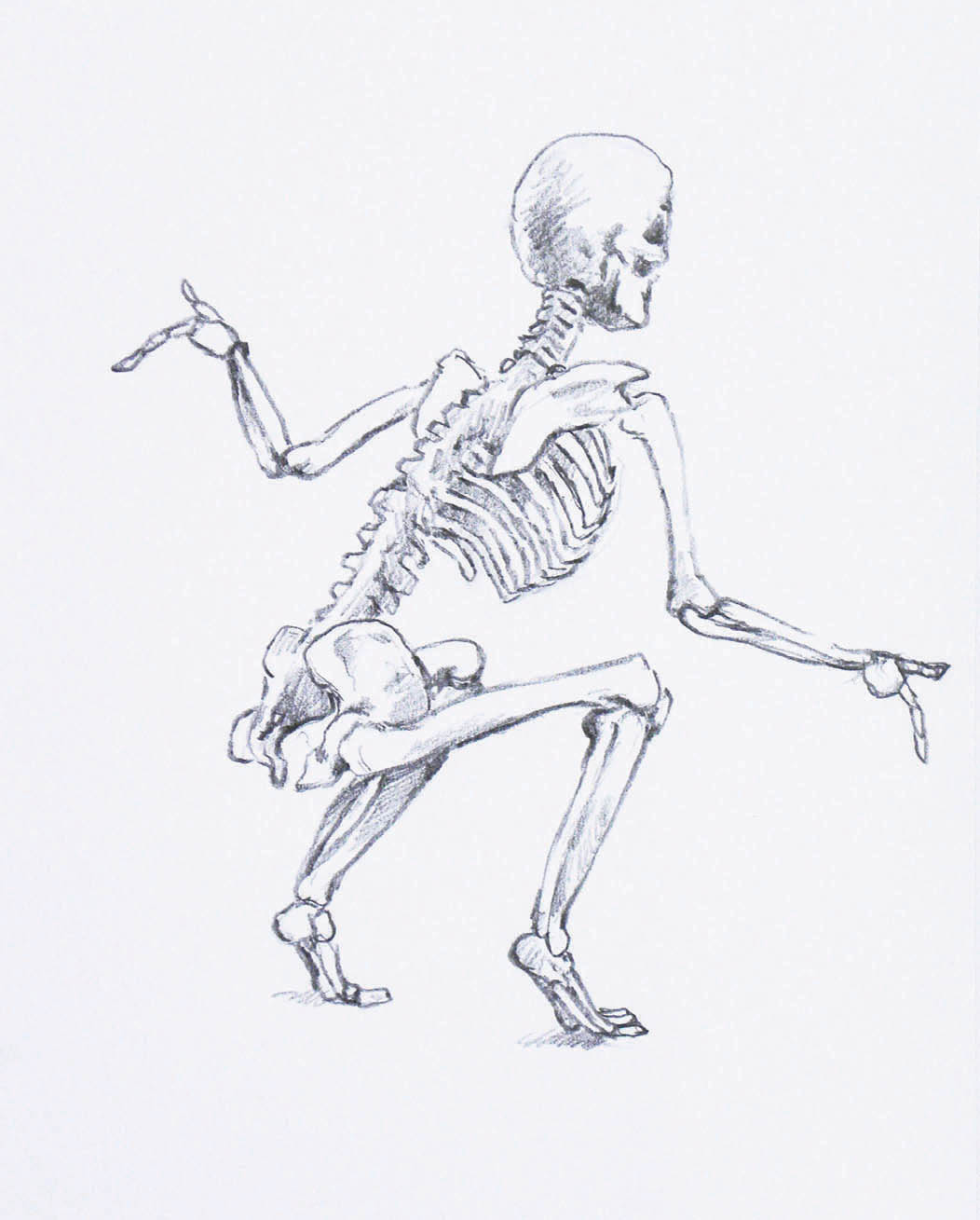

However, the bird skeleton has much in common with that of most mammals, including our own. Most of the joints and major bones are similar. What is often confusing is the apparently backwards-bending knee that birds appear to possess. Birds’ legs, however, are constructed similarly to our own – but the main knee joint is hidden under belly, flank and wing feathers. The backwards-bending knee is in fact the bird’s ankle joint and what we can see of its leg from this point downwards is equivalent to our foot (tarsus). Birds actually stand and walk on their toes.

Birds’ feet also have an anatomical feature unique to them, which enables them to perch on thin branches and even sleep whilst doing so. The tendon arrangements are such that they cause the toes to clench and grip the more the legs flex and relax. The feet can give many clues to the way a bird moves and even how it feeds. In birds of prey and owls, the feet are tools used for catching, holding and killing live food. Typically they have wickedly sharp and curved talons that pierce skin and muscle. Game birds (such as pheasants and grouse) and jungle fowl (or farmyard chicken) have muscular feet and powerful toes with which they scratch the earth to reveal food items such as seeds and invertebrates. The claws are thick and spade-like. Many water birds have long toes that help to spread the weight of the bird, assisting in their manoeuvrability over muddy ground. Jacanas and gallinules can walk over the leaves of floating water plants. Webbed feet enable the bird to push itself through the water efficiently and many different species share this characteristic. Cormorants, pelicans, gannets, auks and ducks are not closely related, but have each evolved this feature.

Pelvic, sacrum and leg structure – great cormorant.

The principal musculature of the bird is involved with its primary function: flight. The pectoral (breast) muscles are large and powerful, which is necessary for flight. The main stroke for powered flight comes from a downwards and slightly backwards movement of the wings. Clearly this creates huge opposing forces against the air as the bird’s wings are brought down through it, lifting the bird in the air. The lifting of the wings is done not by muscles on the bird’s back, but by muscles that are also attached to the sternum (keel). These muscles (supra-coracoideus) curve around to attach to the top of the humerus. When they contract they operate in a pulley-like fashion, raising and slightly rotating the wing. These muscle groups are proportionately very large and can form up to 35 per cent of the total weight of the creature. The way these muscles work is very complex and gives rise to the enormous variability in species flight and in directional movement.

Compare the drawings of the cormorant skeleton and that of the human.

The way the muscles operate can best be seen in birds that hover, in birds coming in to land on a perch, and in stalling flight around sea cliffs.

Getting to know the general anatomy of birds is an essential part of their portrayal. Learning about the specific anatomical variations from one species to the next will help greatly in the depiction of that singular species. For instance many pelagic (ocean-going) birds have similar adaptations regarding their ability to cruise enormous distances by using the air pockets and thrusts formed by the swell of the ocean. Gulls and petrels look superficially quite similar in appearance, but are taxonomically quite unrelated.

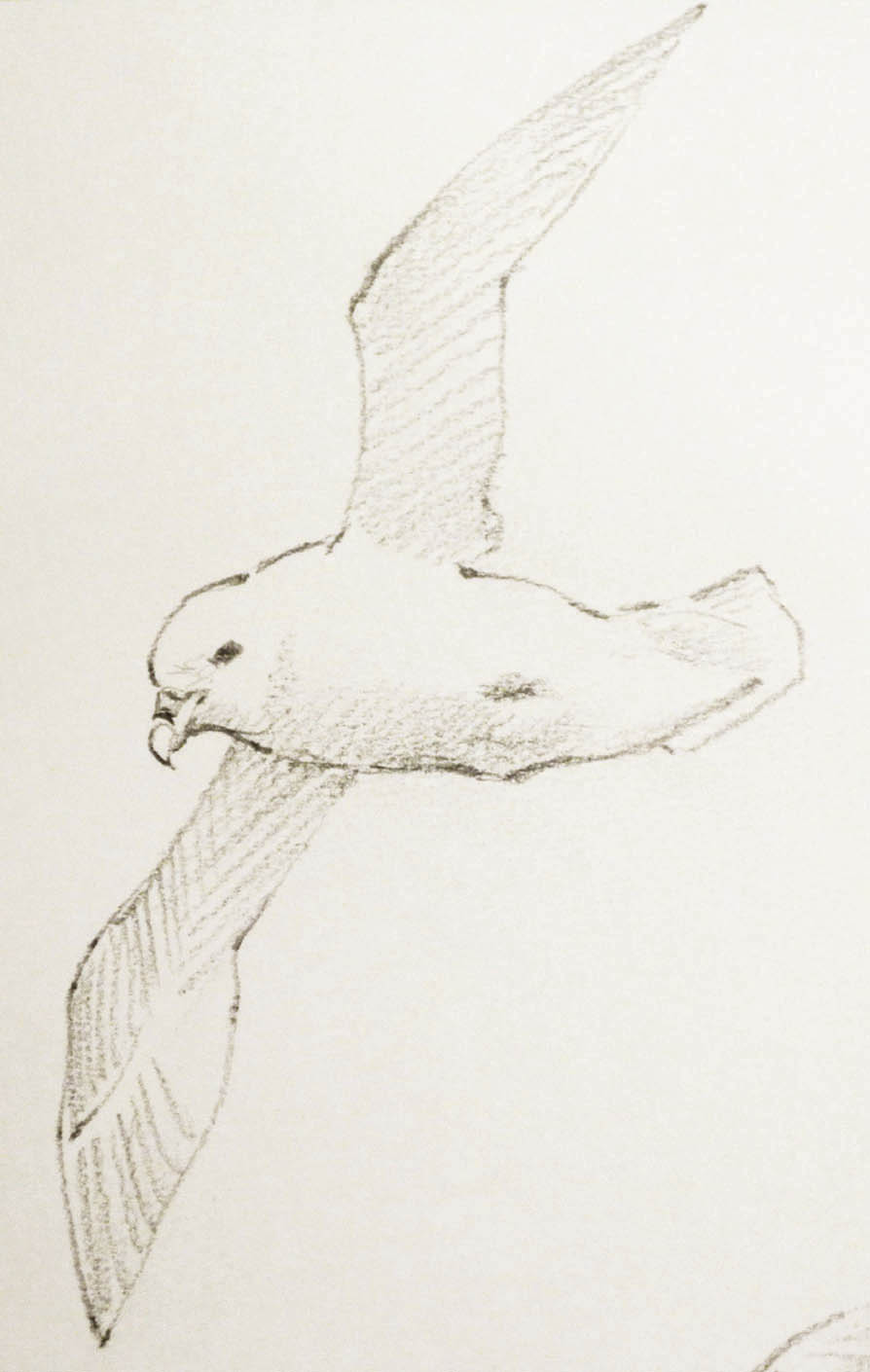

Fulmars are members of the petrel family: true masters of the marine environment. They are able to cruise huge distances seemingly effortlessly by holding their wings stiffly. Their bodies are robust, rounded in section and strongly tapered at either end; it would be difficult to design a more streamlined form.

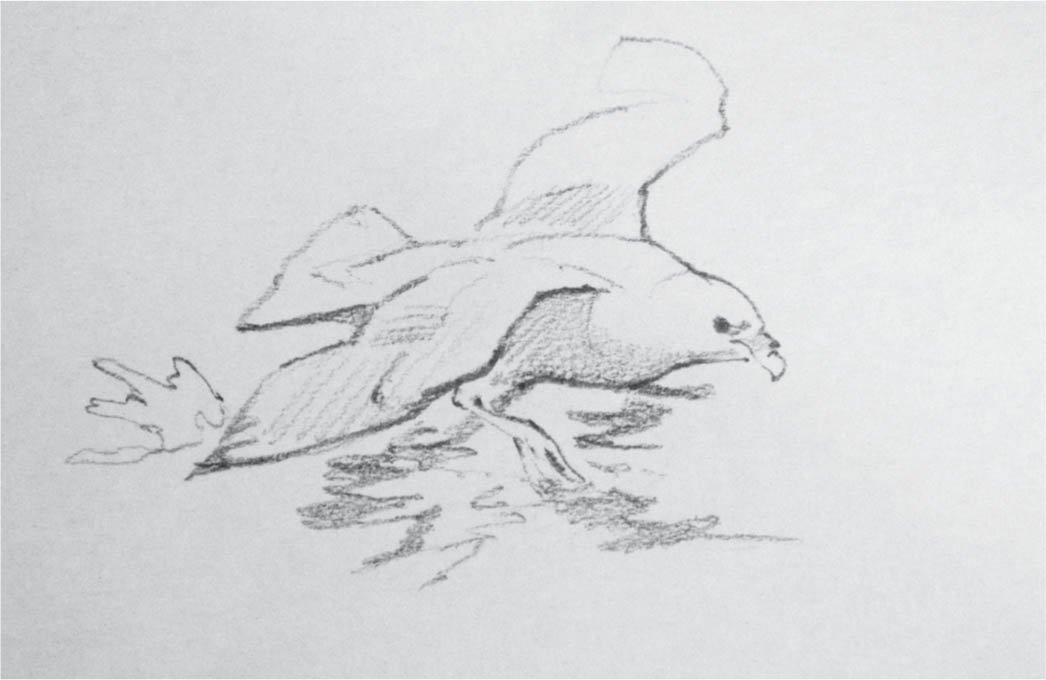

Another aspect of fulmar flight can be seen at their breeding sites, namely sea cliffs. They use their feet as rudders, brakes and stabilizers in the turbulent air around the cliffs. Usually the feet are tucked under the bird’s tail and are lowered when required to perform the functions mentioned above. This enables close control and manoeuvrability in the air, but in extreme conditions and when the bird is soaring through the air, the fulmar tucks its feet up in the forward position, nestling under the abdomen. Here they are secreted under the thick body feathers and are all but invisible. Perhaps the forward position brings more weight to the bird’s centre of gravity allowing for a more dynamic style of flight. When the bird is seen in this mode it could be very easy to think that the bird had lost its legs.

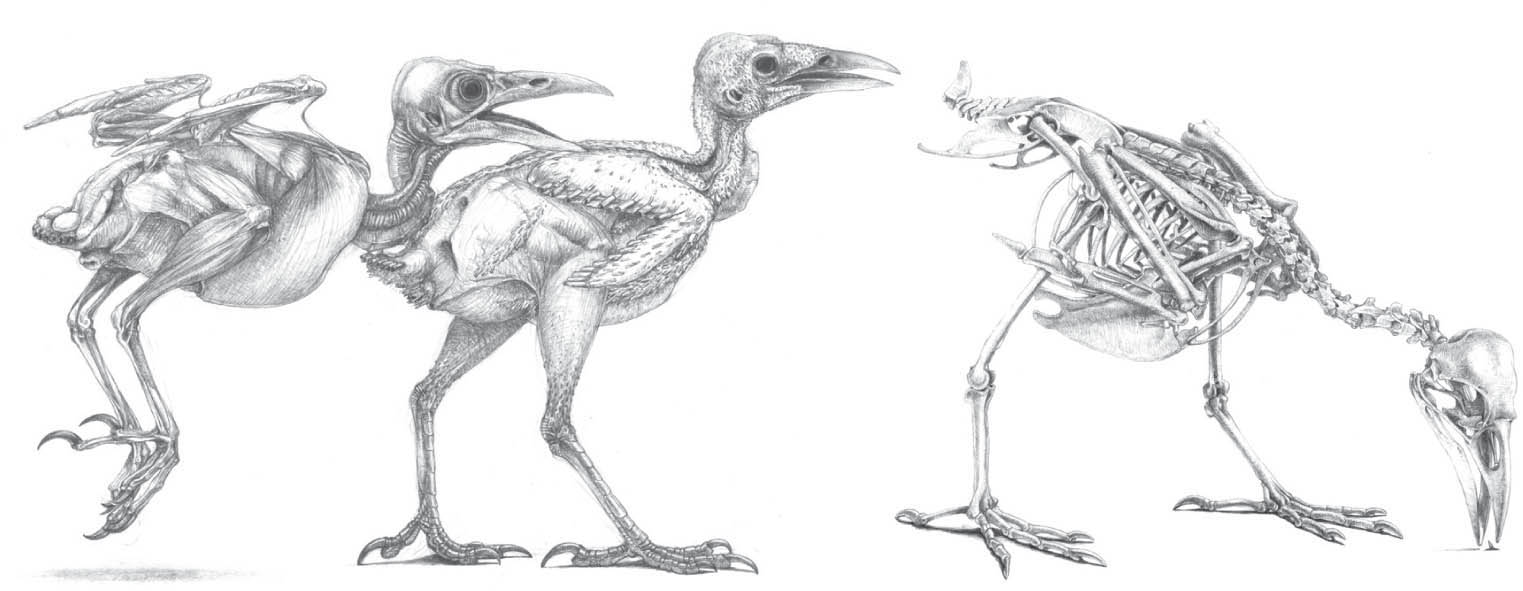

Katrina van Grouw: intricate and detailed studies of mallard musculature, side and back views. Investigative and exploratory work such as this connects science with art.

Katrina van Grouw: rooks showing musculature, feather tracts and skeleton (pencil drawing).

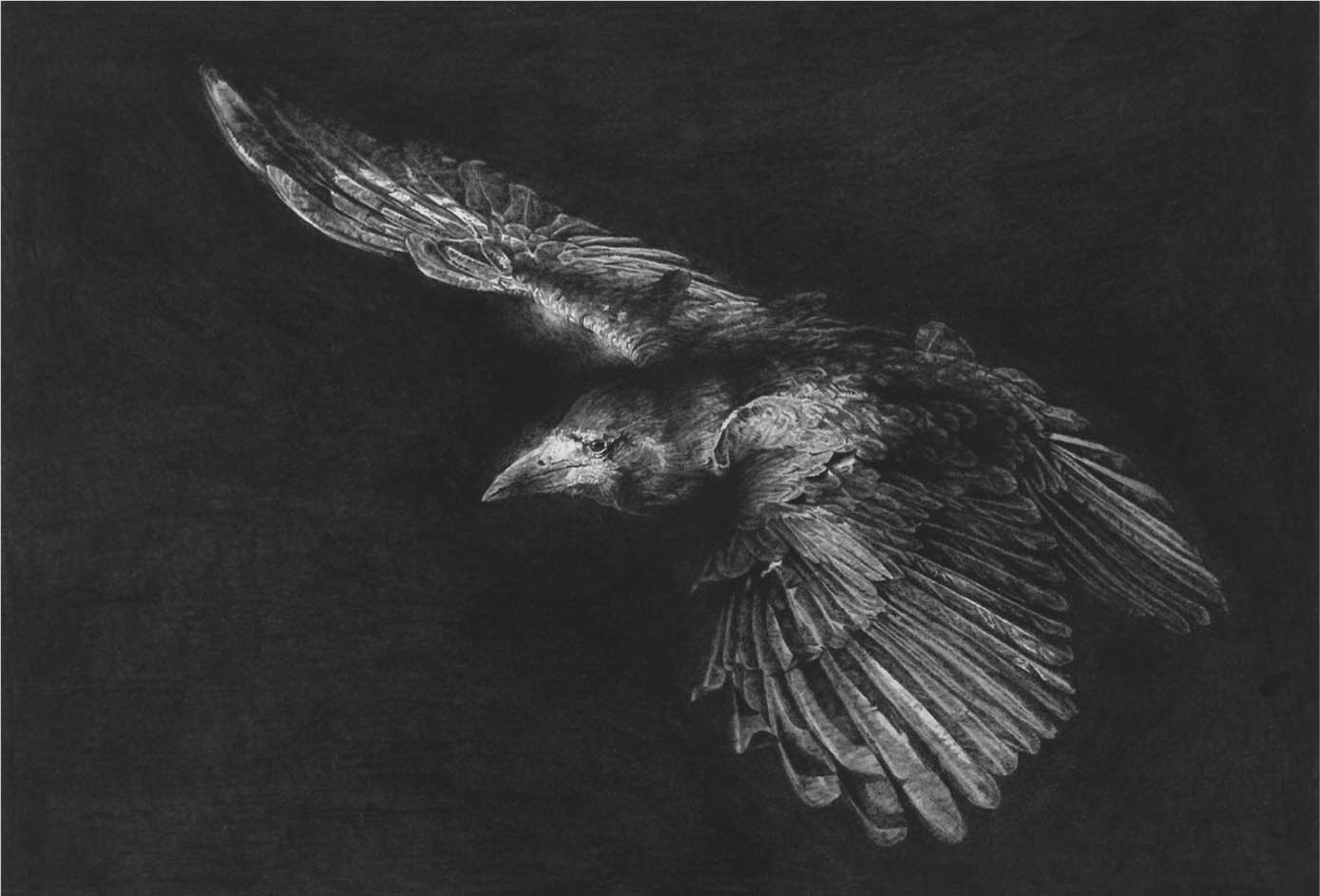

Angela French: rook (graphite drawing).

Pectoral and supracoracoid muscles (wings, sternum and wishbone arrangement).

Fulmars, like other members of the petrel family, spend much of their time at sea. They are opportunistic feeders on morsels floating on the surface. Their feeding techniques include pattering their feet in the water whilst they keep themselves stable near the food item with their wings. When they take off from the water they run along the surface for a few steps before becoming airborne. They also paddle when they are gliding close to the water at speed to keep themselves from ditching in the sea (much as a speedway rider will put down a foot on tight bends). This adaptation makes the bird ideally suited to its marine environment, but it also means they are quite cumbersome on land and have difficulty taking off from flat ground. This is one of the reasons they nest on cliffs: they can simply launch into mid air from a standing start.

Knowledge of the bird’s anatomy combined with an understanding of its habitat is important in capturing the essence of the creature.

In large birds, leg muscles are well developed. The large flightless species apart, eagles in particular have extraordinarily strong leg muscles not only to support their bodyweight, but to perform their primary function – hunting. Eagles take all manner of prey including fish, mammals and birds. The strength to both catch and then subdue the prey is vital for the bird’s survival.

The intricate muscle anatomy is covered with feathers and is therefore rendered invisible. In addition to the main ‘structural’ muscles, each individual feather has a collection of muscles by which the feathers can be raised and lowered. This action, although individual in act, usually affects a regime of feathers simultaneously – the feather groups assembled over the body. It is the arrangement of these groups, and the relative status of them, which actually gives rise to the perceived form of the bird. Therefore, paradoxically, the general structure of the bird is determined not by the massive pectoral (flight) and thigh muscles, but the thousands of tiny follicle muscles that control the status and appearance of the feather masses. This arrangement also accounts for the way a bird can alter its shape and posture at the flick of a switch.

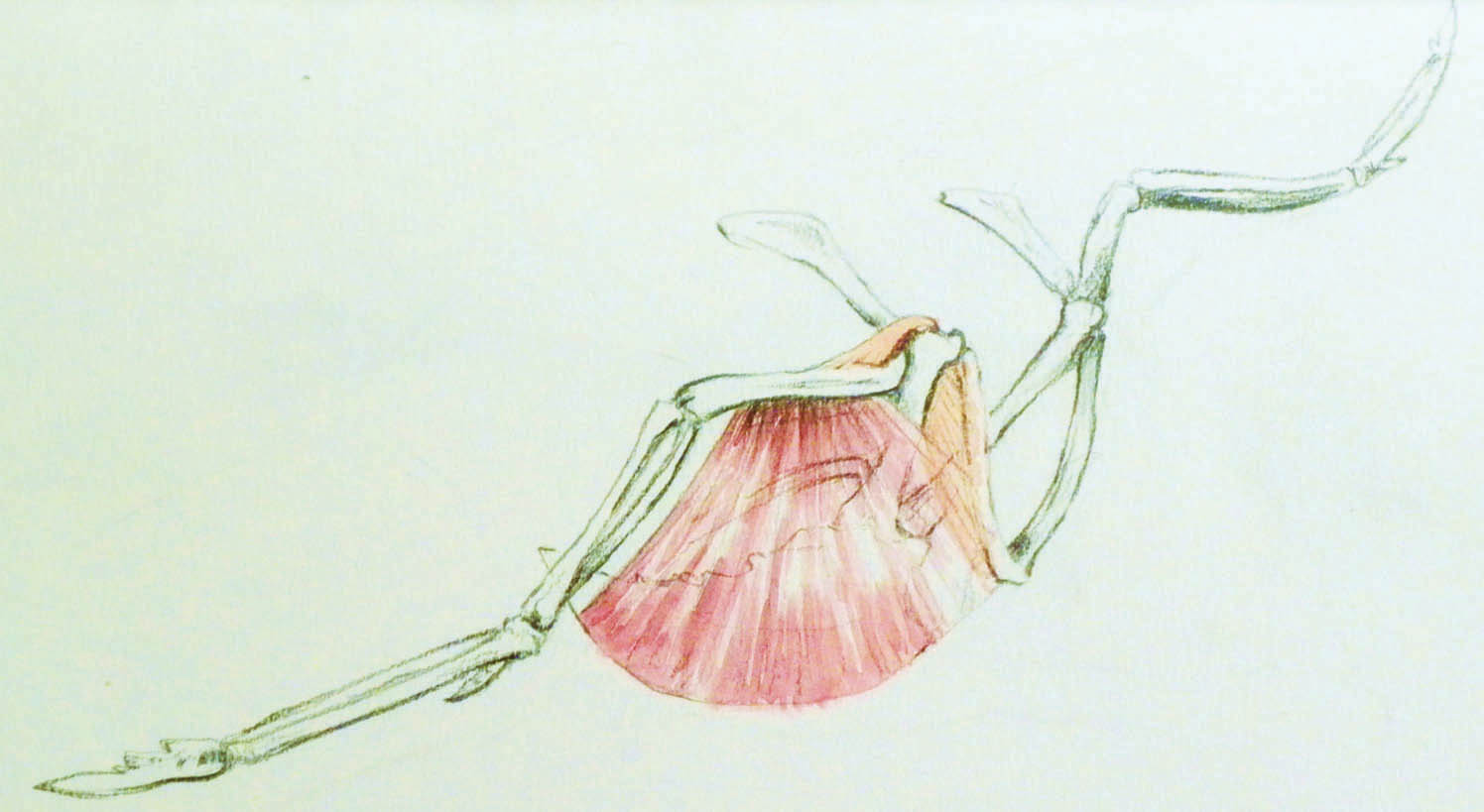

Fulmar showing position of pectoral muscles and, secondly, massing of weight directly under wings when holding legs in forward position.

Tim Wootton: fulmar studies.

Tim Wootton: dead fulmar. This post mortem watercolour painting shows the barrel-shaped body and narrow wings typical of the species; note the arrangement of the tubular nostrils, giving rise to the family name of ‘tube-noses’ given to albatrosses, shearwaters and petrels.

FEATHERS

Feathers are a feature unique to birds. There are different types of feathers which perform various functions. Birds have an insulating layer of soft, fluffy feathers called ‘down’ feathers. These are covered by profile feathers but may occasionally be seen when the bird’s plumage is lifted in breezy weather. There are feathers that enable the bird to fly; primary and secondary flight feathers on the wings are augmented by wing-covert feathers. Tail feathers assist in the control and steering of the bird in the air and balance the bird when perching or running. Feathers on the top of the head (crests) can be raised in display or agitation. The appearance of a bird can alter rapidly when it puffs out its feathers.

A bird’s plumage consists of many individual feathers, arranged into groups that have specialized and specific functions. Unlike mammals, which are generally uniformly covered in hair, a bird’s feathers grow in specific lines and groups called feather tracts. In between the tracts are bare areas of flesh. The groups can usually be quite readily seen, particularly on a preening bird.

A bird preens its feathers to keep them in tip-top condition. Feathers are constantly under stress from wear and tear and periodically are dropped and replaced in a process known as moulting. Generally in adult birds this is done once a year after the birds’ breeding season and in readiness for the onset of winter. In some birds, the process of moulting flight feathers is done gradually and individually so enough are retained at any one time to enable the bird to keep on the wing. In some cases huge gaps are visible in the flying bird – waders, gulls and crows can look extremely scruffy at certain times of year, and watching their rapid wing beats it’s amazing they can keep airborne at all. Some species lose all their flight feathers at the same time – ducks in particular. Certain species go on special ‘moult migrations’ and congregate at historically favoured areas where they lose the ability to fly and only return ‘home’ after the whole process of moulting is complete.

Tim Wootton: waxwings – feeding shape-shifters.

Paul Bartlett: fairy martins preening. Collage and acrylic paint.

There is a close layer of downy feathers that trap air close to the body and act as insulation. There are groups of feathers specifically arranged for the purpose of flying (the same feathers in a few specialized cases for underwater propulsion). Some feathers create cryptic and effective camouflage and can be displayed to mates and potential competitors. With all these functions to perform, the bird has to maintain its plumage in good condition and regular preening helps in this. At the base of its tail, a bird has special preen glands from which it collects and disperses oils over its plumage. This helps in waterproofing the feathers as well as general conditioning.

C.F. Tunnicliffe: cartoon for loafing barnacle geese.

Charles Tunnicliffe: loafing barnacle geese – wing and leg stretching. Tunnicliffe would often make small colour compositions (derived from drawings and colour studies made in the field) before embarking on his delicate large-scale watercolours.

To watch a bird going through its habit of preening, and its routine of leg and wing stretching and then resting, is an extremely absorbing and, for the artist, fruitful time. During these actions the birds form the most elegant shapes and graceful contortions. During preening, birds will remain in the same area for some length of time and it pays dividends for the artist to learn where best to observe these rituals at close hand. Learning to draw such actions is a very rewarding labour.

Although the individual movements of preening birds may only last for a few seconds at most, with careful observation you will notice that it will perform similar tasks repeatedly over a period of time. This allows any previously started drawings to be resumed.

The main thing to concentrate on when trying to convey the bird in action is to discern which bits of the bird are moving and to concentrate on those primarily. For instance a curlew wing-stretching will also flex the same-side leg simultaneously. Look for the general shapes being made and block them in quickly onto the sheet. Don’t be concerned over finishing a drawing; just get individual studies of moving parts onto the page. When the bird moves from its position, stop drawing. Scratching is a rapid action. Watch carefully where the bird holds its wing when scratching certain parts of its neck and head – sometimes the leg will go over the folded wing and other times the wing is partially extended, allowing the scratching leg to slide between it and the bird’s body. Note how the body adjusts to counterbalance the action.

Wing anatomy of mallard duck: (top) main flight feathers attached to wing bones of right wing; (middle) top view of left wing; (bottom) underside of right wing showing coverts overlapping main flight feathers.

Barry Van Dusen: a group of godwits scratching, preening and settling down to doze.

Juan Varela: Studies of drake shoveler preening. (First published in Entre Mar y Tierra/Between Sea and Land, Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.)

Tim Wootton: preening black-tailed godwit and blackbird.

The purpose of preening feathers is to keep them in good condition, but to also keep them correctly positioned. The bird may attend to individual feathers, but its intention is to create a unified mass of that particular feather group. The feather groups may be seen as a community working toward the same goal. There are several different communities of feathers on the bird’s body. When drawing the bird’s plumage it is worth bearing in mind that fact and to draw the feather groups. It isn’t necessary to draw each individual feather; in fact this approach may prove counter-productive in your aim of rendering a faithful image of the bird. Colour and pattern should be more important than detail.

Jocelyn Oudesluys: yellowthroat wing- and tail-stretching – a delicate study of behaviour and balance.

Robert Bateman: Canada goose wing-stretching.

Tim Wootton: osprey. A pencil study investigating the shape and perspective of feathers as they lie across the different planes of the bird’s neck and back.

EXERCISE: MAKE A MODEL TO SHOW THE PERSPECTIVE OF A FEATHER

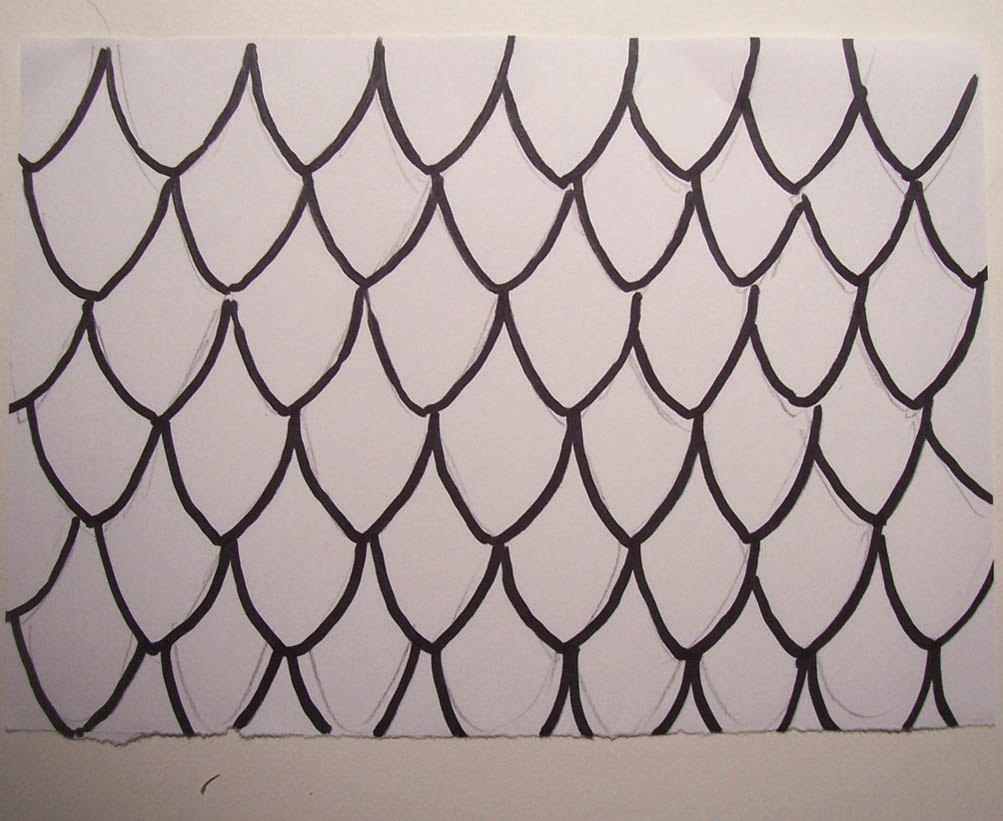

Take an A4 sheet of paper and lightly sketch a diagonal grid in pencil. Using a felt-tip pen, draw scales/feathers using the grid as a guide.

Roll the sheet into a tube and fasten using sticky tape and lay it down.

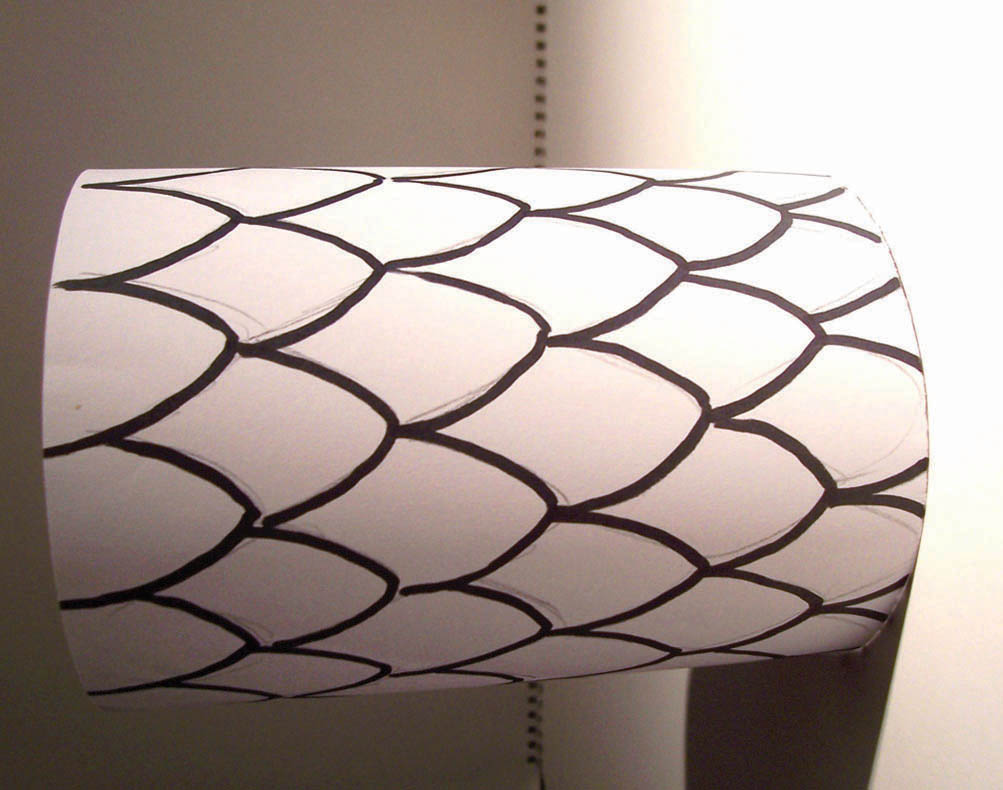

Observe how the shape of the ‘feathers’ alters as they start to get to the edge of the curve. The top (and bottom) feathers are very flat relative to the ones in the middle of the tube which aren’t being affected by perspective quite as radically.

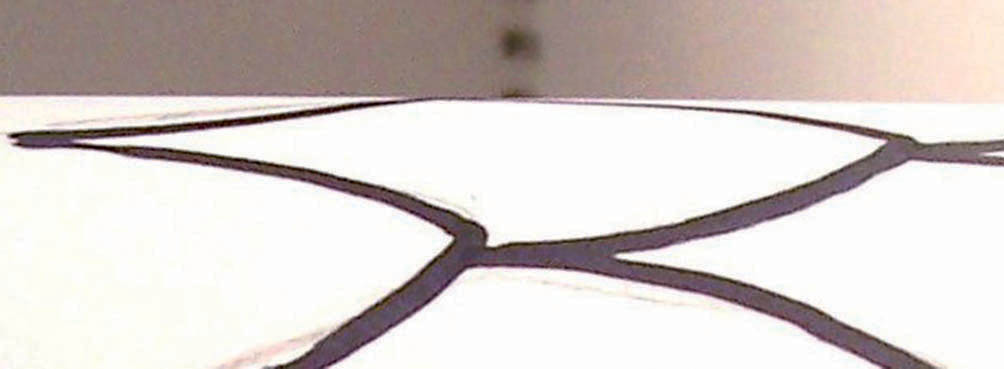

Feathers at the edge of the curve are compressed flat.

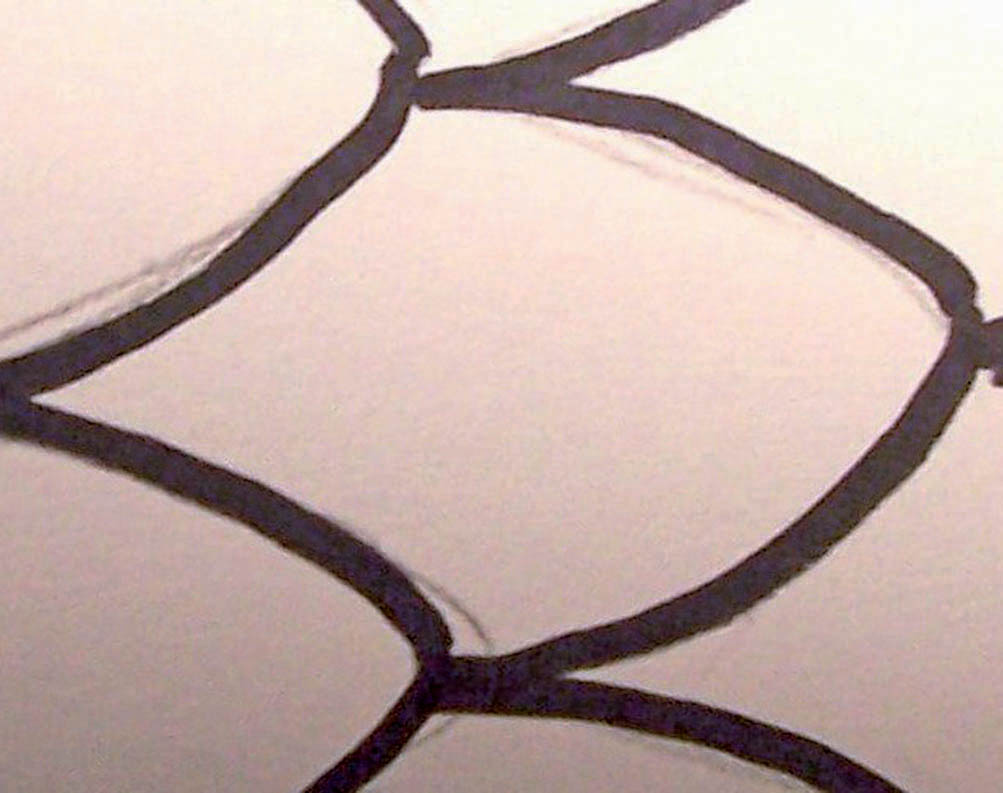

Feathers in the centre are less distorted. Also note how much light is hitting the top edge, so much so that the very black lines are almost washed out.

These are subtle but important changes to basic shapes which occur in nature.

Model showing the perspective of a feather.

Although feather groups can be massed together and treated collectively there are occasions when individual feathers may be drawn; wing and tail feathers are obvious candidates and so are hackles and crests (neck and head feathers) and scapular feathers. Where this is the case, pay attention to the way they lie across the body, or stand up from it. Often the shape of the feathers can assist in moulding the shape of the bird, as can the way light reflects from them and the shadows that form underneath them.

Ed Keeble: peregrine falcon. Pen and ink study. Careful drawing of the feather markings sculpt the faint undulations across the bird’s breast, whilst the direction expresses the roundness and solidity of the subject.

Mike Woodcock: Ordinary – Extraordinary. The artist finds inspiration in the commonplace and seemingly unremarkable: a European starling and man-made structures make for an interesting juxtaposition of textures.

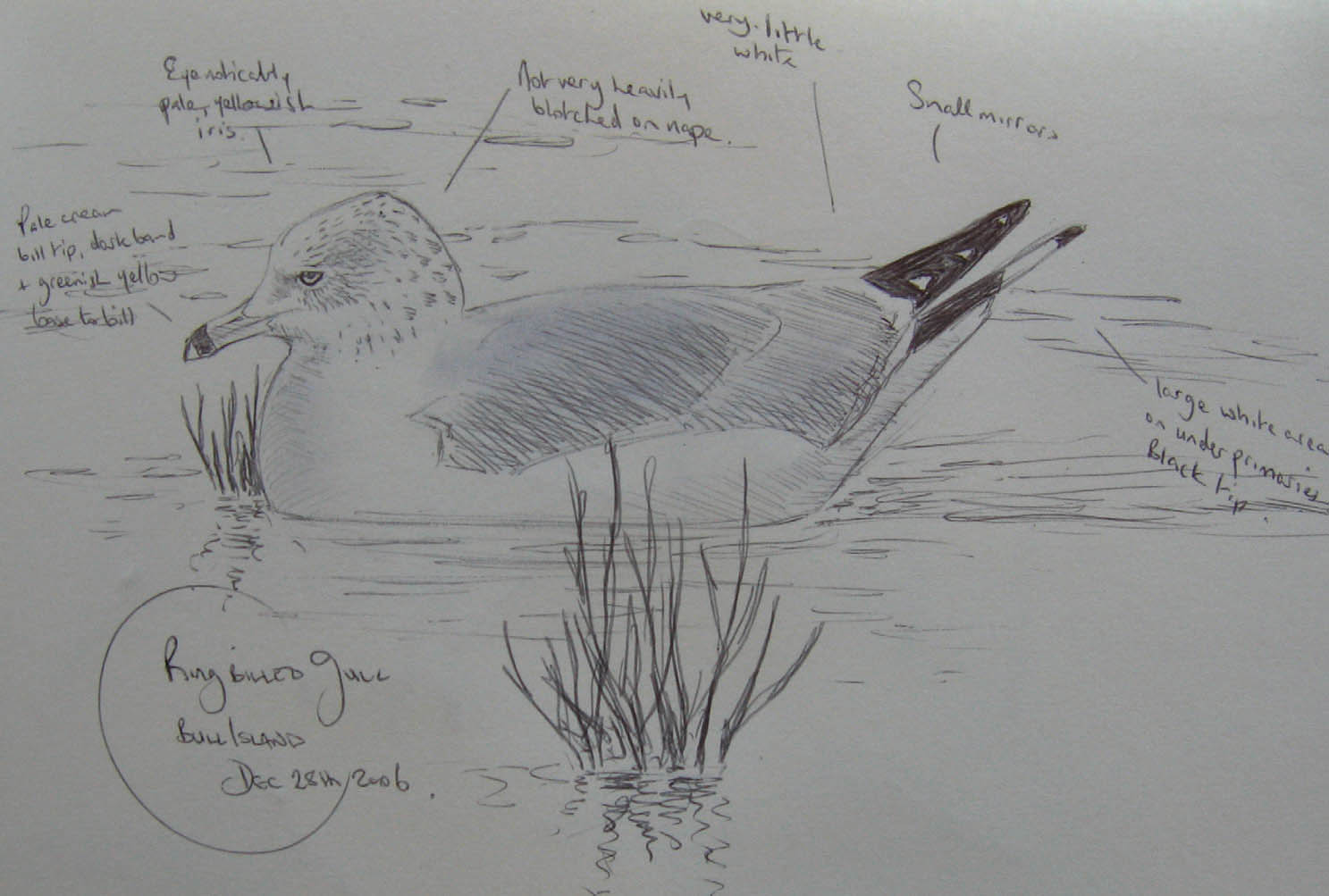

Alan Dalton: ring-billed gull in Ireland. Field drawing specifying the important features of this local rarity from America. Gulls typically have very soft and fairly featureless plumage – the directional hatching and soft tones describe both texture and form simultaneously.

Frank Van Boxtel: Caillou Ruffle. The intimate nature of the portrait and the nature of the bird’s plumage allow the artist to indulge in the texture and structure of the individual feathers, but this isn’t detail for the sake of detail; each painted mark contributes to the essence of the form and the spirit of the bird.

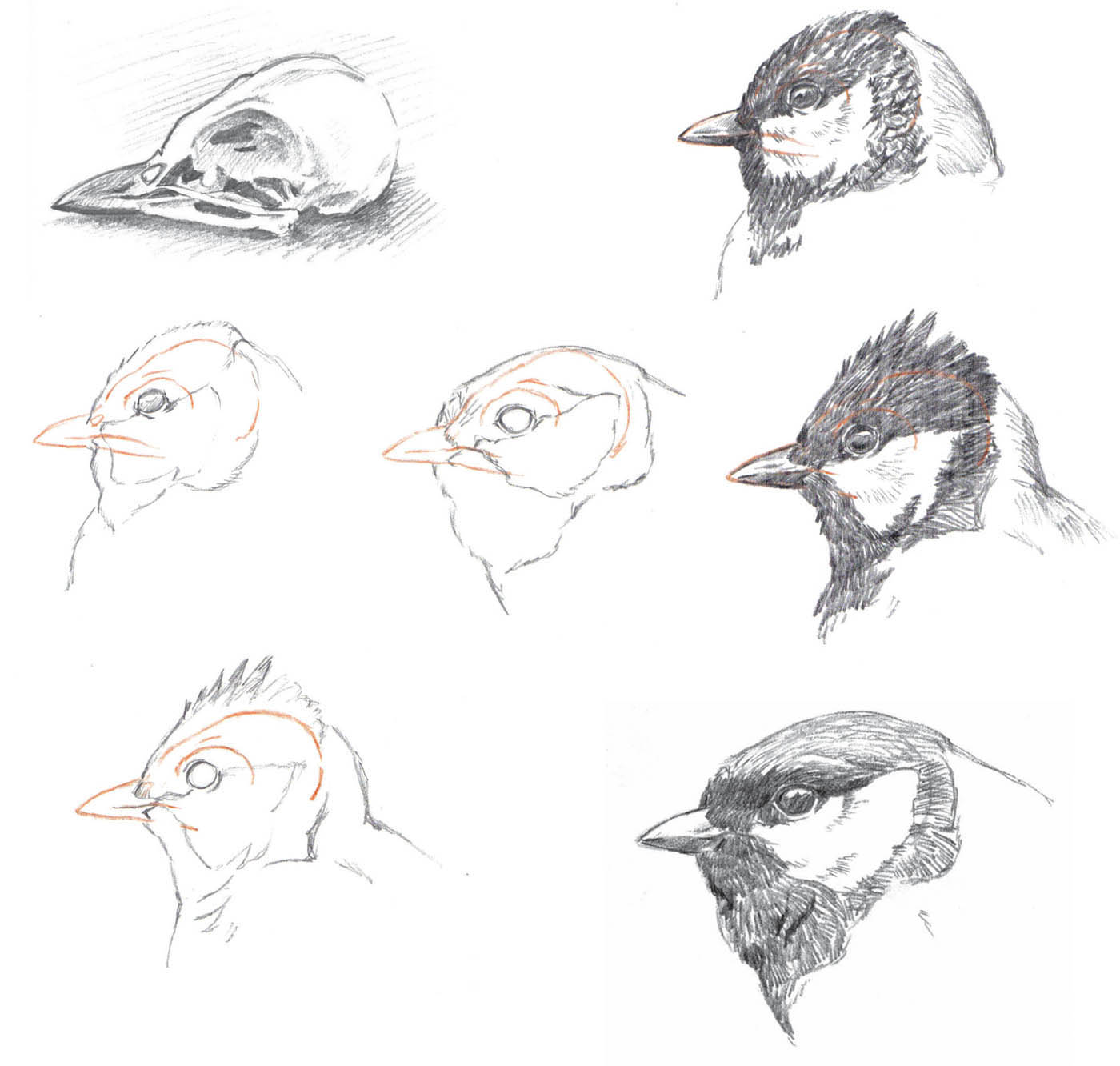

Although the great tit’s internal structure remains constant, it can alter its physical appearance (and therefore send visual signals) by controlling certain groups of feathers.

A defining feature of birds is their beaks and this feature also reveals much about the habit of the species. The bill (beak), although diverse in shape and size, is generally used for the specific purposes of feeding and preening. Not only is there huge variety: the long and terminally spatulate beak of the spoonbill; the immensely strong and powerful bills of the hornbills and parrots; the delicately up-curved bill of avocets and down-curved of curlews and hoopoe; thick, short finch-beaks; fine, slim insect-eating beaks of warblers; and all manner of colours and textures – each is ideally suited to the purpose. The flamingos have evolved a bill that accommodates their general anatomy and diet – they feed upside down. When depicting a bird, the scale, shape and relationship between the bill and eye are critical in capturing the character of the species. Pay great attention to this aspect of the bird.

Even within the finch family, there is a variety of bill types, although their function is principally the same (to extract and crush seeds).

A: goldfinch (dextrous bill for picking thistle seeds).

B and C: bullfinch (crushing fruit seeds).

D: greenfinch (‘multi-purpose’ bill for eating soft fruits and seeds).

E: hawfinch (giant cherry-stone crushing bill).

F: crossbill (removing seeds from pinecones).

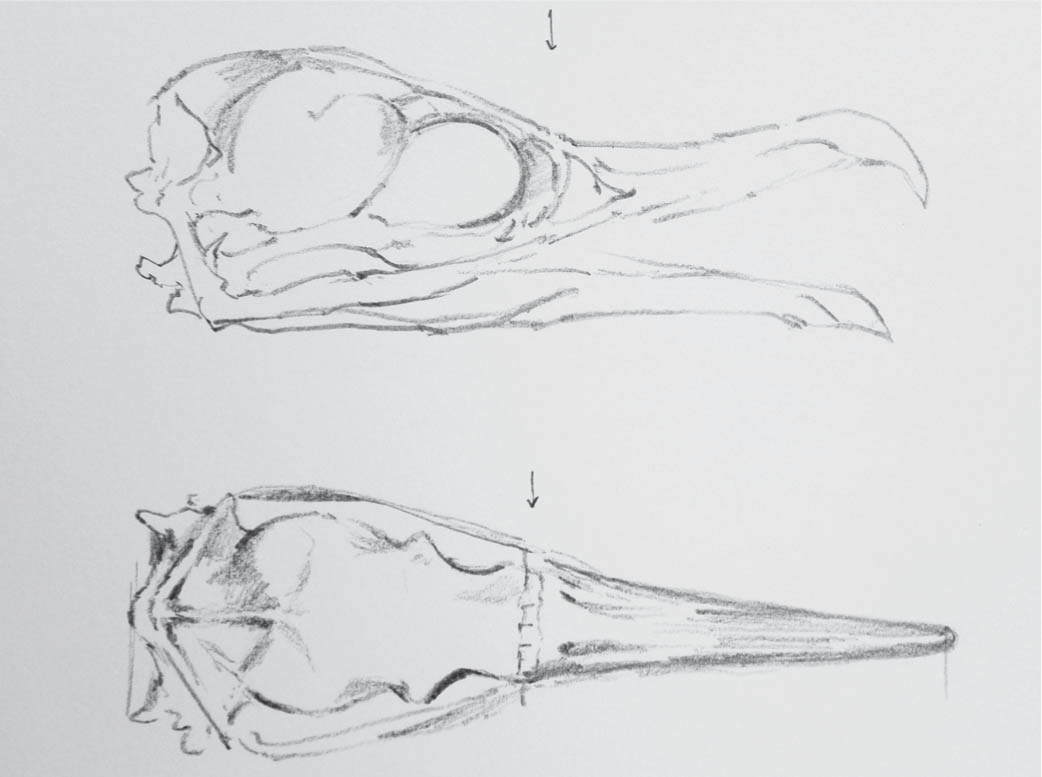

Tim Wootton: skull of a great cormorant. Note how the character of the bird is encapsulated in this structure; the second sheet of drawings highlights the hinge arrangement on the upper mandible. It’s obvious that birds open their bills where the jaw hinges, but perhaps not so clear that they can also flex their upper mandibles too, giving them greater dexterity when catching and manipulating food items.

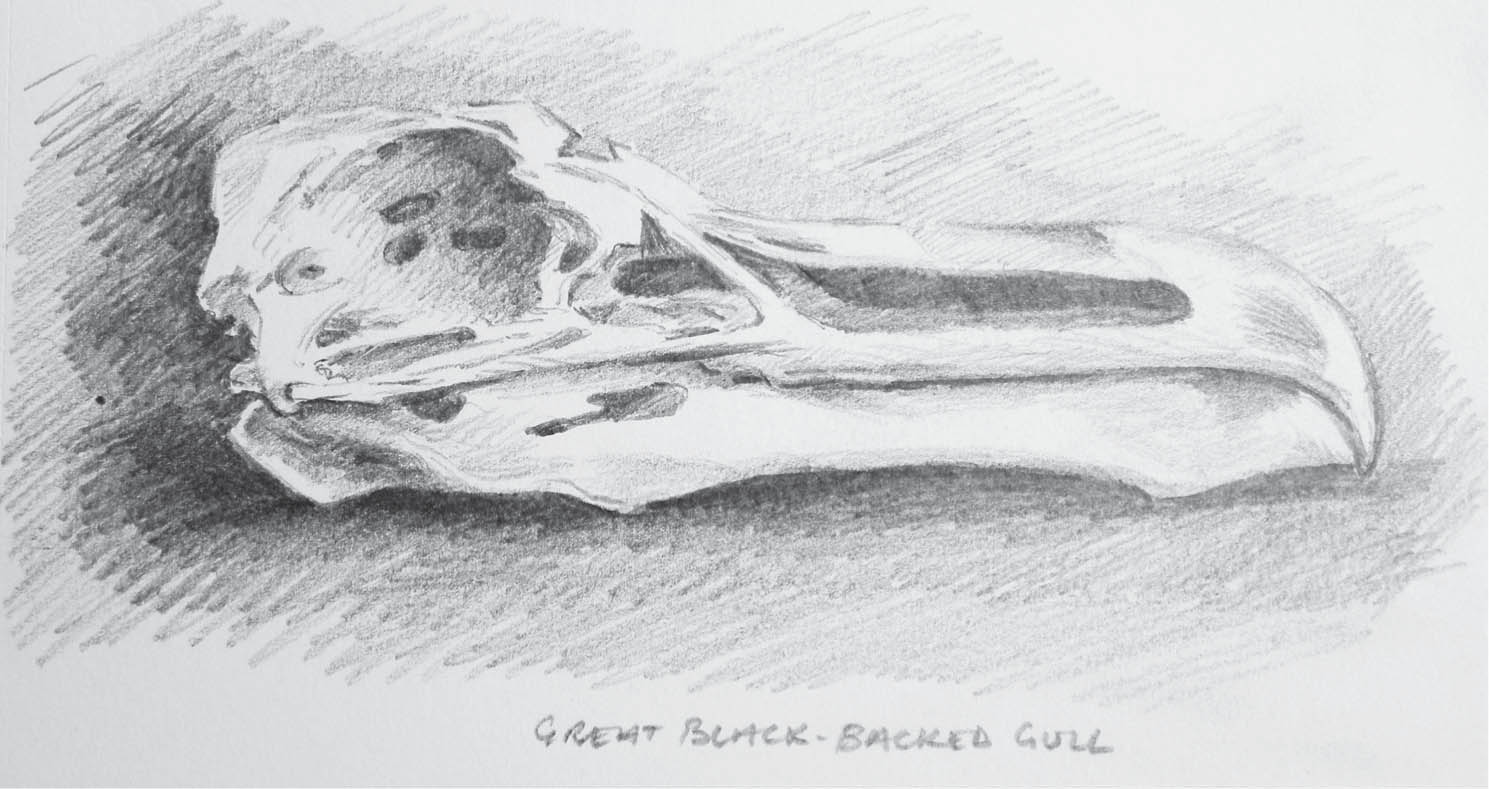

Tim Wootton: skull of a great black-backed gull. It’s apparent just from this skull what this species is all about: killing prey by bludgeoning (smaller birds and their young), eating eggs and catching fish.

Tim Wootton: bird portraits. The arrangement of facial features gives each bird a certain look, or character if you like. Catch this and your bird will not only look like the species it’s meant to portray, but also have a certain life to it.