Robert Bateman: Pribilof Cliff.

DRAWING BIRD TYPES

Oh, I don’t know, Father, is there a difference between crows and blackbirds?

Melanie Daniels in The Birds

Considering the range of size and shape, the many different ways they move and the variety of habitats they occupy, birds could be considered one of the broadest areas of study, particularly if one starts to delve into biology or migration, or any of the many other specialized areas. Air, land, sea (both on it and under it), extremities of latitude and altitude – some spend half the year in one hemisphere and the rest in the other; some spend half their lives on frozen wasteland; some spend nearly all their lives on the wing and some cannot fly at all; some migrate over 20,000 miles every year and others range less than a few hundred yards all their lives – their plumage encompasses every colour of the rainbow (plus black and white) and each species is specifically and perfectly adapted to being what it is. This is undoubtedly a big and fascinating subject.

As with all big subjects, it’s best to break them up into smaller, more digestible chunks. In this section we’ll look at a selection of bird types: that is, those that share many similar characteristics of anatomy and appearance. It will, inevitably, be the merest slice of the fodder available, but it will address some of the major areas that could occupy the bird artist and maybe open the doors to further investigation.

We’ll look at bird types that are easily recognizable and that are easy to study – those that are easy to approach and get a decent view. As your interest in birds increases, so will your knowledge of them, as will your ability to catch them in your mind’s eye and on paper.

Adam Bowley: Melanesia kingfishers, identification plate. The bill shapes, postures and overall silhouette identify these birds as being closely related yet they each represent a different species; in fact there are about ninety different species of kingfisher in the world. Although a scientific illustration, the artist introduces the occasional slight pose change as the eye follows the lines of birds; one or two with a downwards glance break up the repetition and give the birds a subtle sense of activity.

When starting out, it’s best to approach subjects that are easily located and stay fairly still – anyone who’s ever watched a wren flitting through shrubbery, appearing momentarily and then disappearing only to reappear yards from where it was last seen, can appreciate the problems in trying to capture the creature in pencil, and how daunting this would be to the beginner. Therefore, although still not easy, a domestic mallard on the local pond would seem a much more accessible proposition.

In the anatomy section, it was apparent that all birds share common characteristics. In this section we’ll be focusing more on the specific similarities which can allow us to group certain birds together.

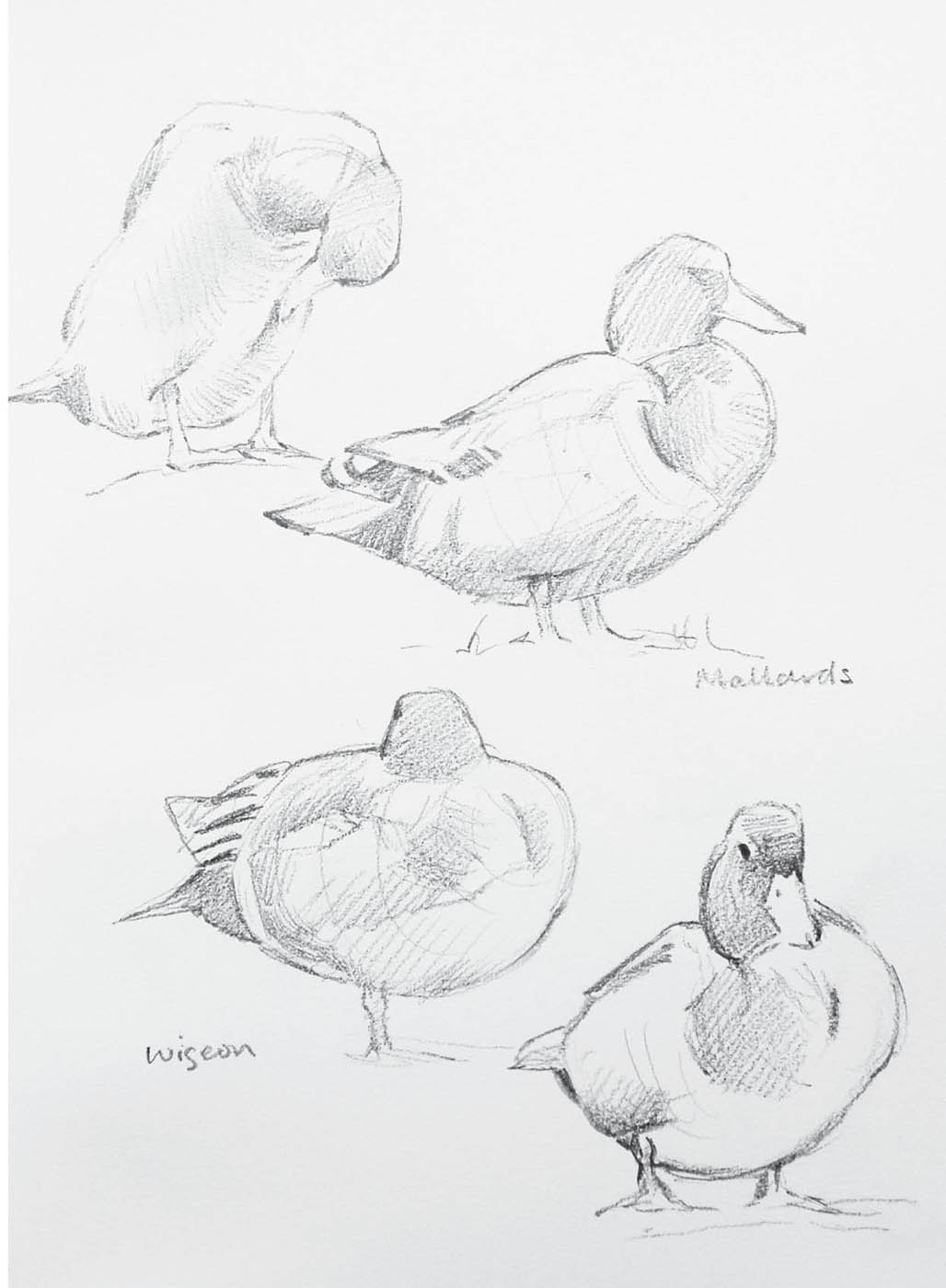

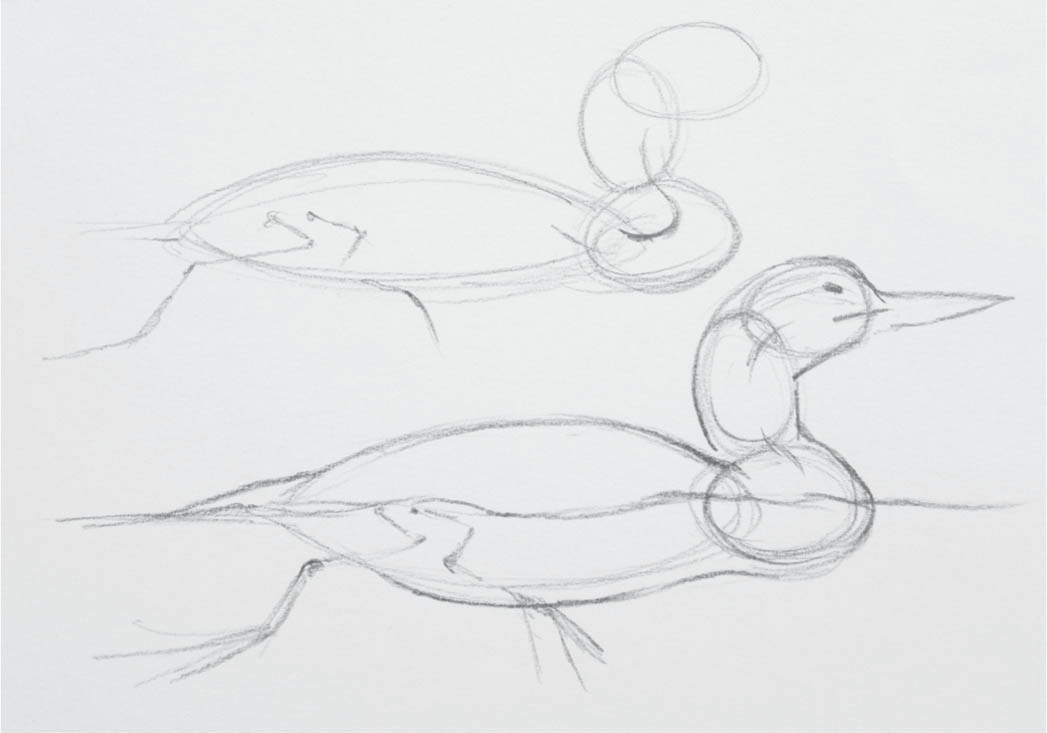

DUCKS

Although there are many different species of duck across the world, each with its own specialities and appearance, they share similar outward characteristics and for the purposes of drawing them we can use the mallard, or its domesticated form, the farmyard duck, as a model. Ducks have barrel-shaped bodies and long necks, which are often tucked in and inconspicuous until the bird starts to feed, or fly. The arrangement of the duck’s neck and head can cause many draughting problems. The back end of a duck is generally conical and quite muscular. Pay attention to the rear end of a duck when drawing it – it helps to describe motion and balance.

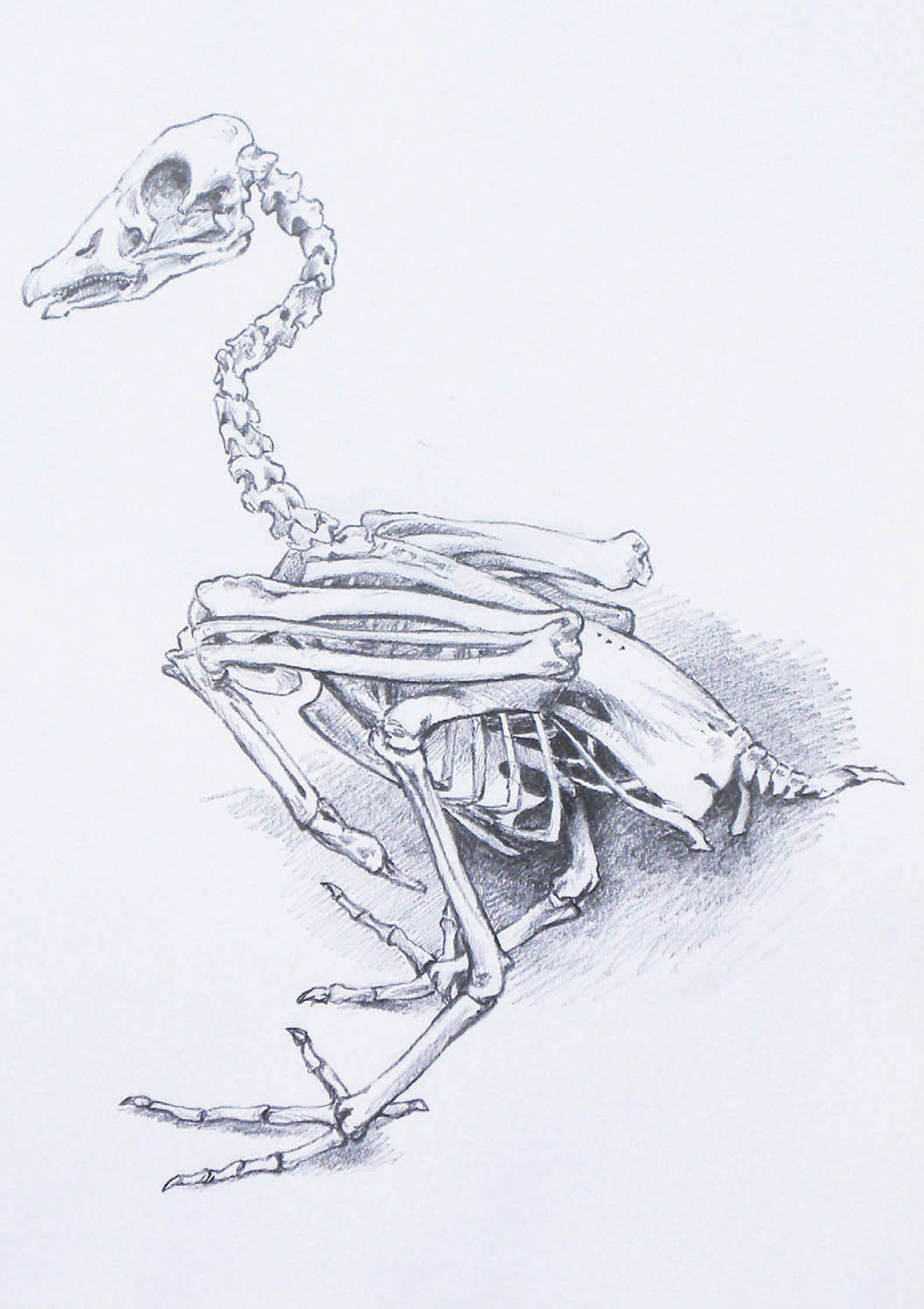

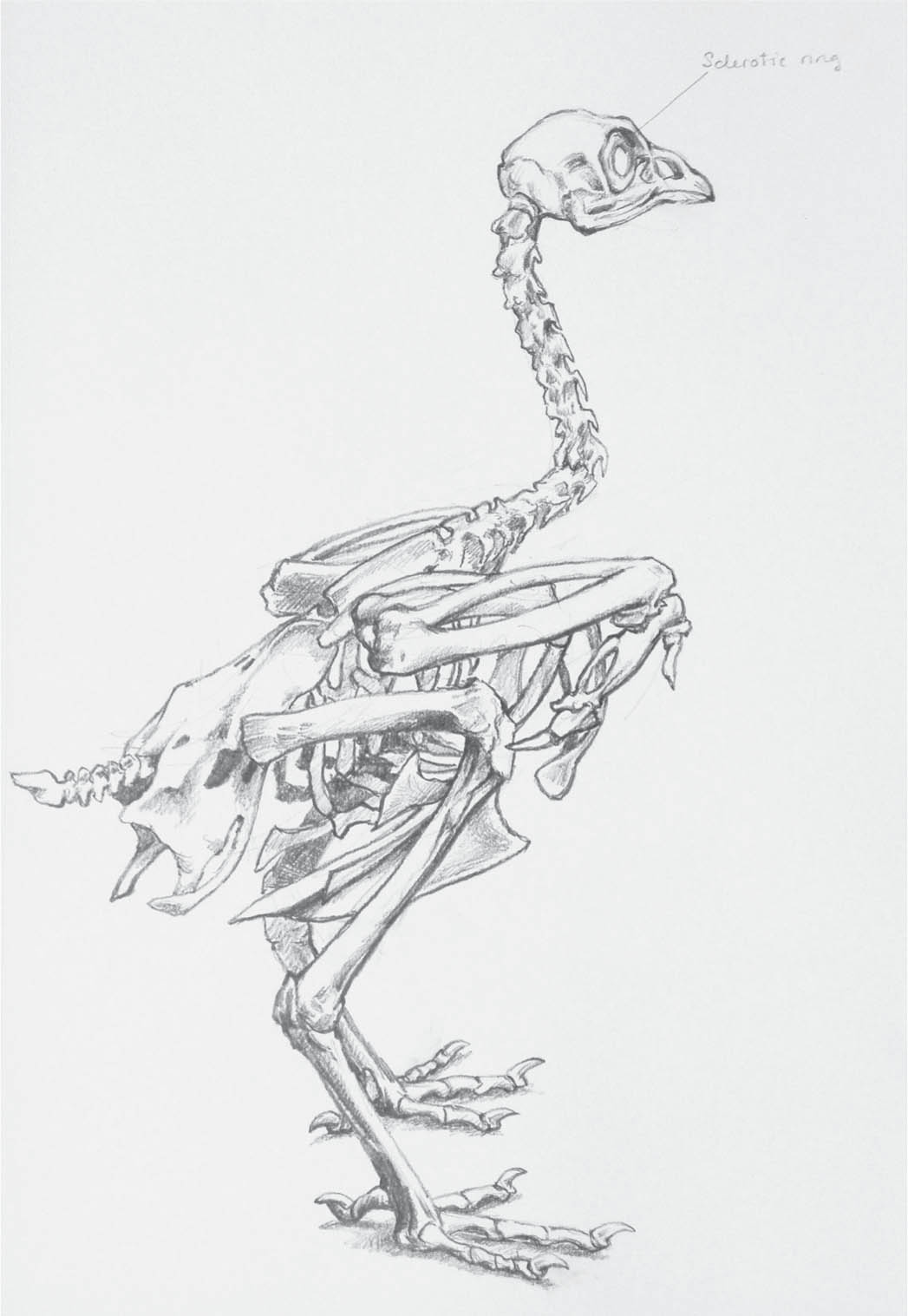

Tim Wootton: a duck’s skeleton is stocky and robust. The neck is long and dextrous.

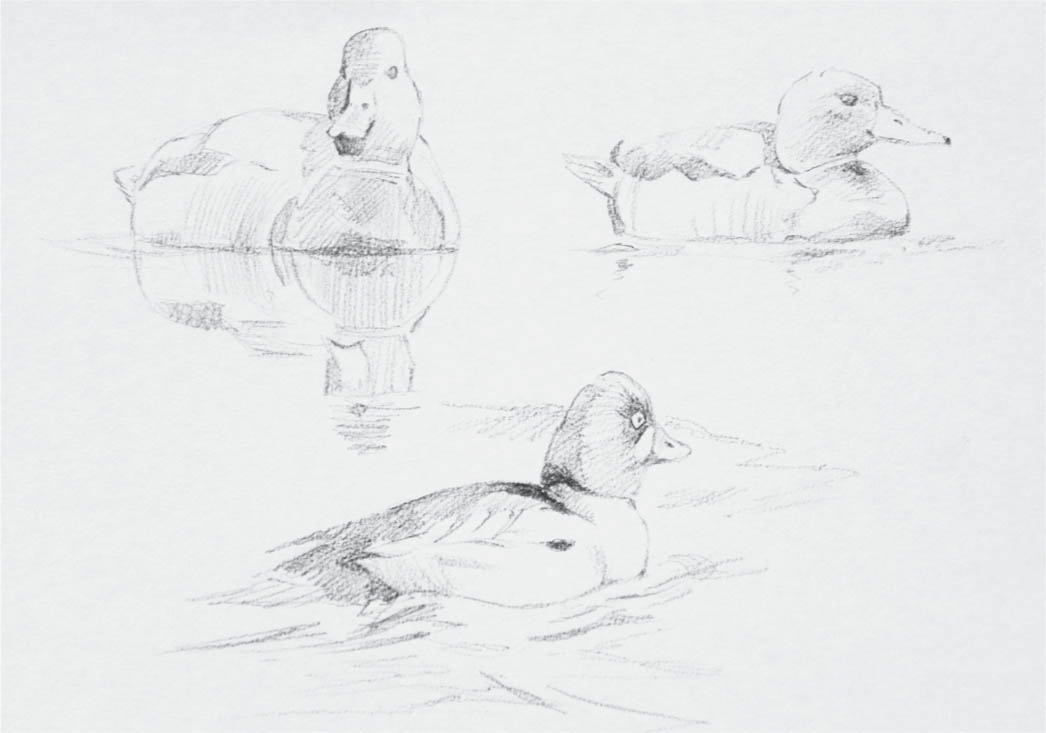

Tim Wootton: a group of eiders (three drakes and one duck). Note the half-open wings on the three birds nearest; the distant bird has its wings covered by flank and scapular feathers.

Peter Mathios: mallard drake. Structure and softness – the artist accentuates the natural contours around the bird to describe the solidity and roundness of the form. Typically much of the wing is hidden.

Tim Wootton: duck posture, neck shapes and angles.

When on the ground or swimming, a duck’s wings are usually tucked away out of sight, hidden behind flank feathers and scapulars. Often all that can be seen is the speculum (the brightly coloured patch of secondary feathers) and the primaries (wing tips). In some diving ducks, however (eiders), the wings are regularly obvious because they remain slightly open between each dive. They use their wings to propel themselves under the water.

When observing ducks on dry land, note the depth of the birds’ bodies and how rounded they are. Look also at the position of a duck’s head when resting: the neck is folded back, extending the bird’s body to the front and the head is about a third of the way back.

David Bennett: shelduck family and avocets.

Tim Wootton: swimming ducks.

Tim Wootton: drake wigeon at rest.

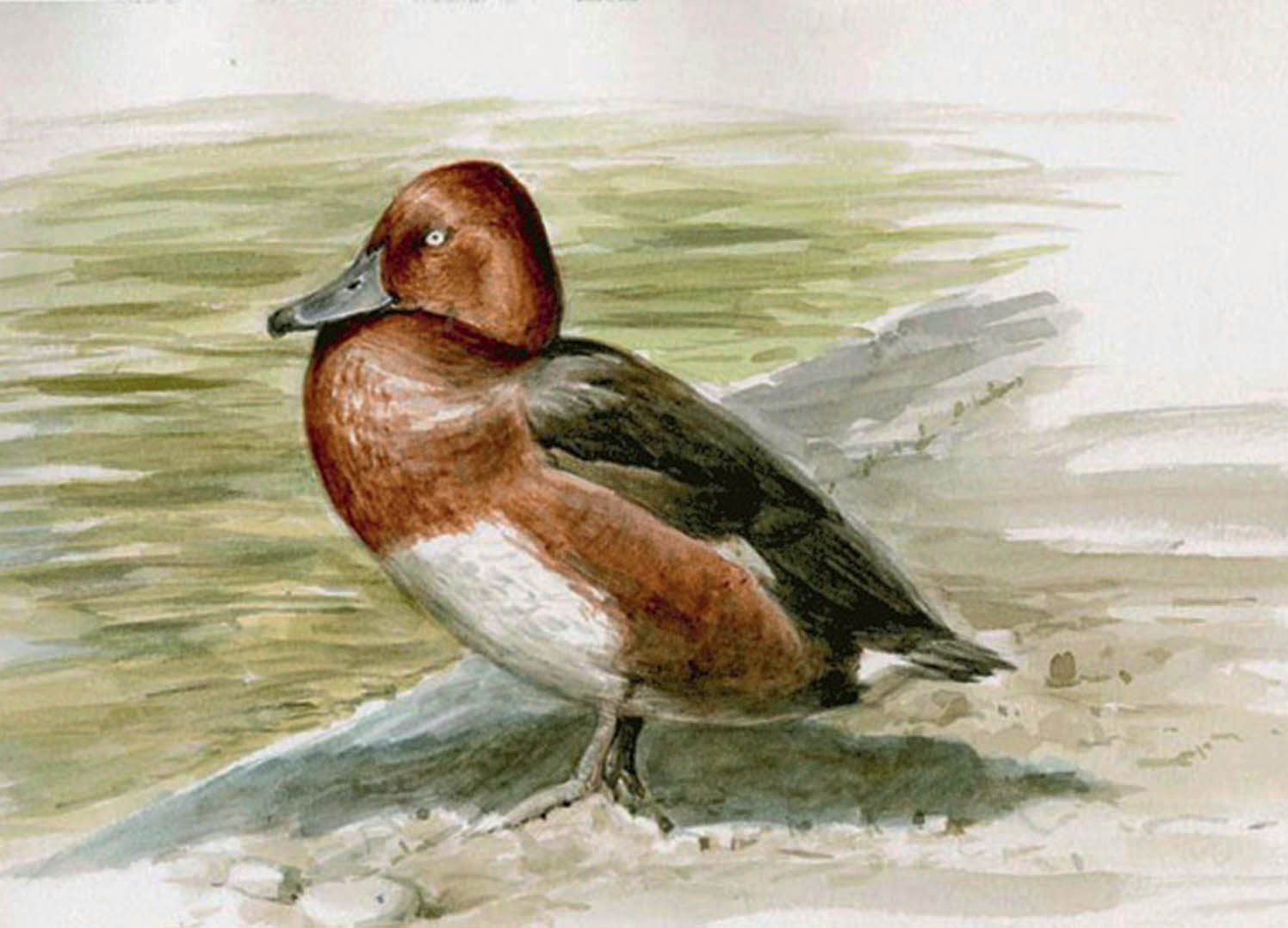

Paschalis Dougalis: ferruginous duck.

A duck’s head doesn’t sit right at the front of its body; always look for that point of balance. Compare this with the swimming birds; imagine how much or little of the bird there is underwater. Ducks have a slightly flattish belly which helps with buoyancy. Their feathers are perfectly waterproof and this often shows as a slight gloss (particularly after diving or swimming), so there will be reflected and direct highlights to contend with and render.

GEESE AND SWANS

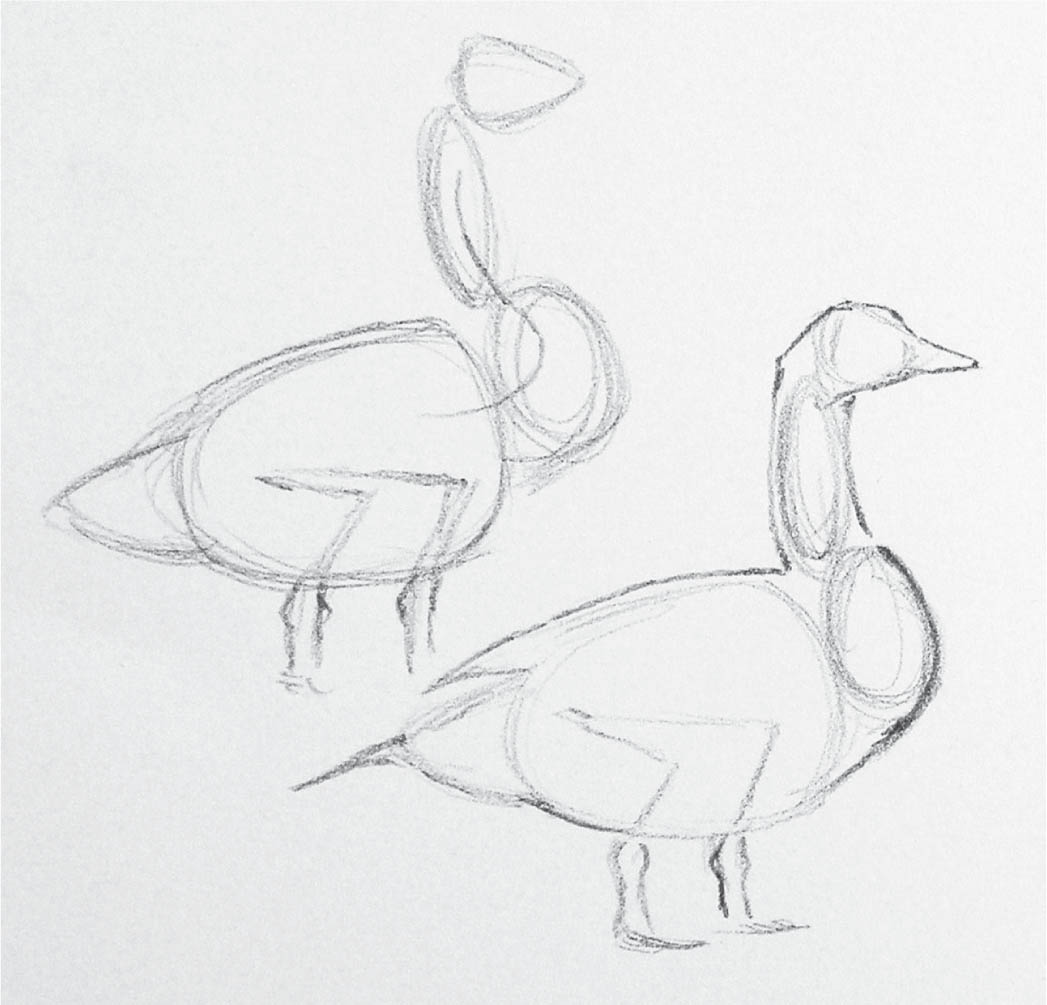

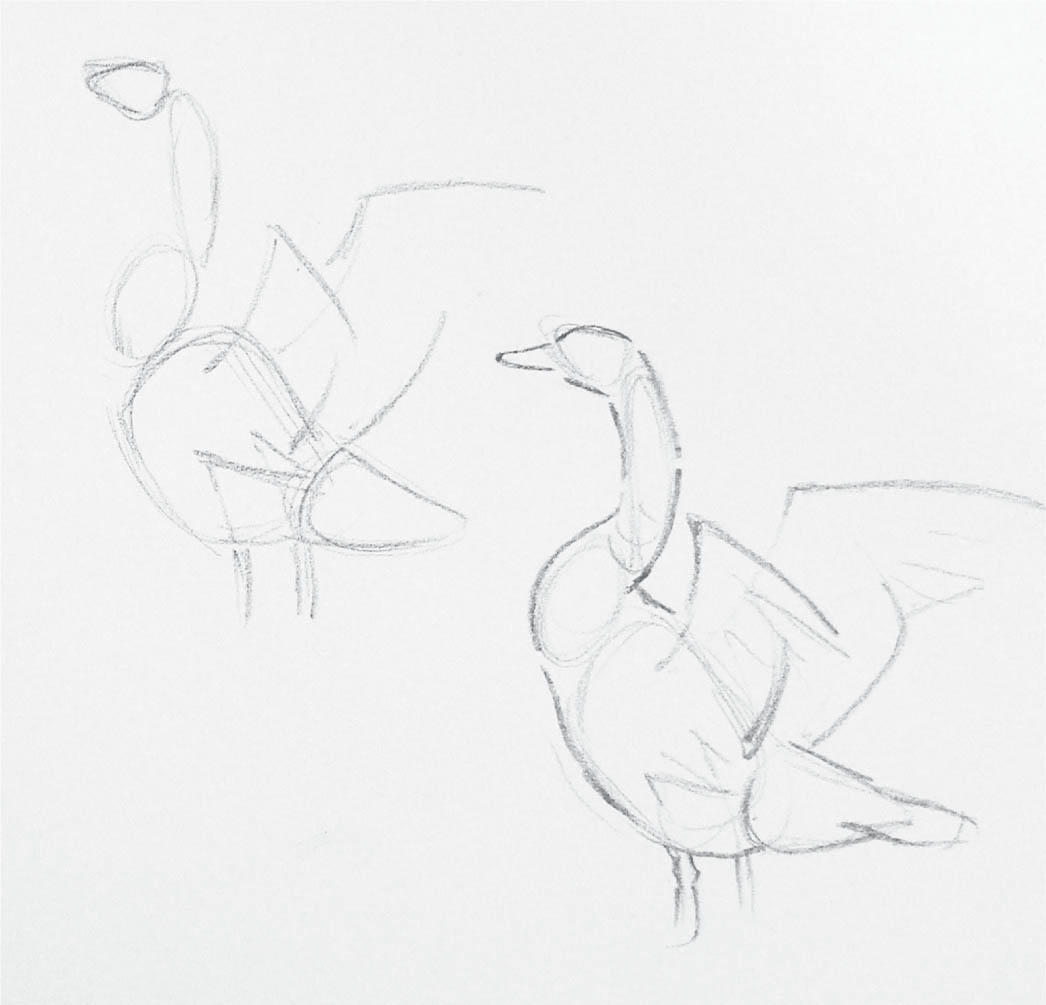

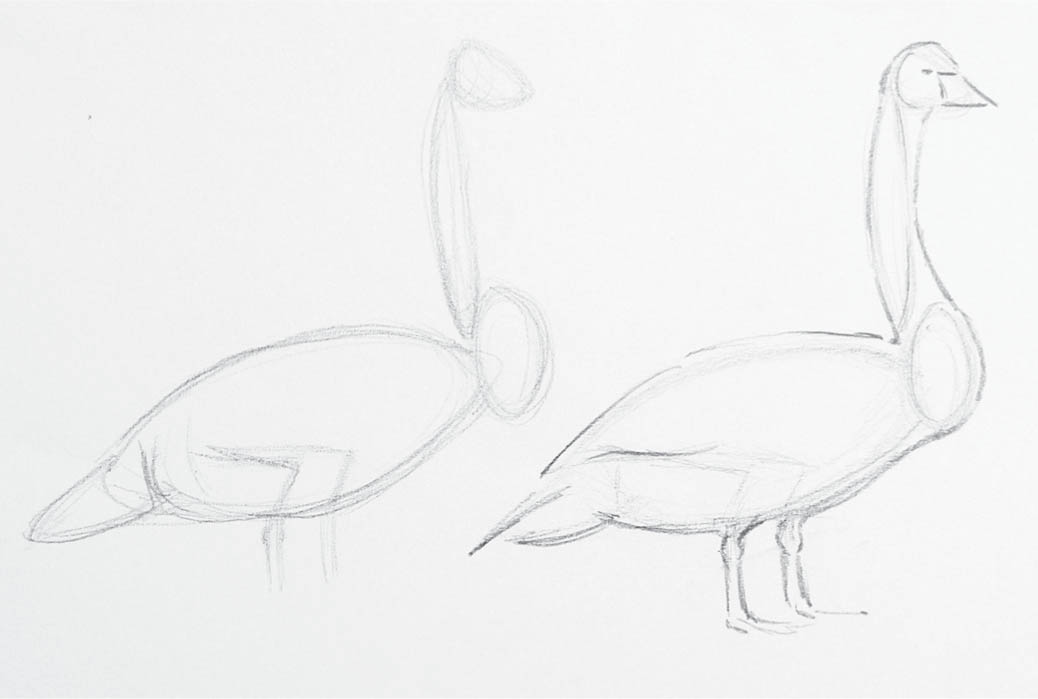

Geese and swans can be fairly approachable, particularly on ornamental lakes and in wildfowl collections. They are wonderful subjects when you are starting out drawing birds from life because of this, and because their physical structures are reasonably easy to see and understand.

Generally they have lozenge-shaped bodies with long, slim necks. They have large wings (to support their weight), which are visible on the bird in the field – both geese and swans show large secondary feathers when at rest. Many geese have a scalloped effect across their upper backs and breasts, formed by differently coloured edges to the feathers in these areas. When drawing them, use these features to assist in unravelling the complexities of their form.

Tim Wootton: greylag goose post-mortem study.

John Threlfall: whooper swan and pink-footed goose.

Tim Wootton: goose skeleton.

Tim Wootton: geese.

Paul Bartlett: swans.

Tim Wootton: swans.

DOMESTIC FOWL AND THEIR RELATIVES

Perhaps the best known of all birds, the farmyard chicken is derived from the jungle fowl of Asia. In some domestic breeds, their native ancestry is evident in both plumage and behaviour. Relatives, allies and similarly structured birds include the pheasant, grouse, partridge, quail and turkey. Getting to know how to draw the domestic chicken will prepare you for many of the shapes and movements you will come across in lots of wild birds. Besides learning to draw them, watching hens will reveal the way a bird’s plumage functions and what they do to keep it in good working order. Cock game birds have a variety of ruffs and hackles adorning their heads and necks and quite often have areas of colourful bare skin on their faces and crowns. The feather masses are well defined and they respond to threat and other environmental stimuli as would wild birds; therefore you will see them scratch and peck, fight, drink, dust-bathe, preen and eventually roost. They are superb models, not to be overlooked.

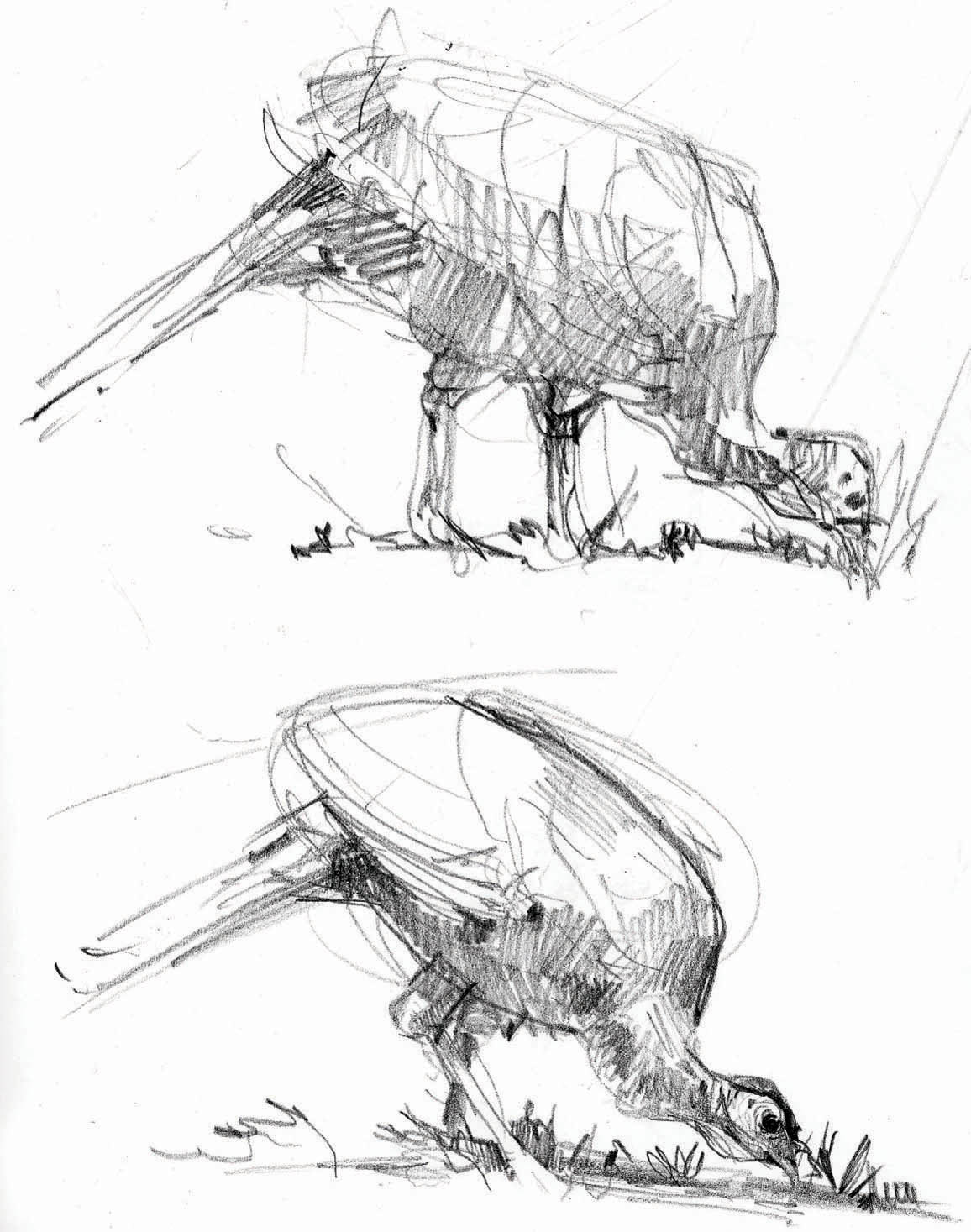

Tim Wootton: skeleton of a domestic hen.

They have long, powerful legs and strong fleshy feet with quite wicked claws (the mature cockerels have vicious hind claws – ‘spurs’ – which rake the flesh when they kick). With their long necks and relatively small heads they have a distinctively reptilian expression. They are omnivorous and will catch and eat mice and voles as well as the more usual diet of seeds and berries.

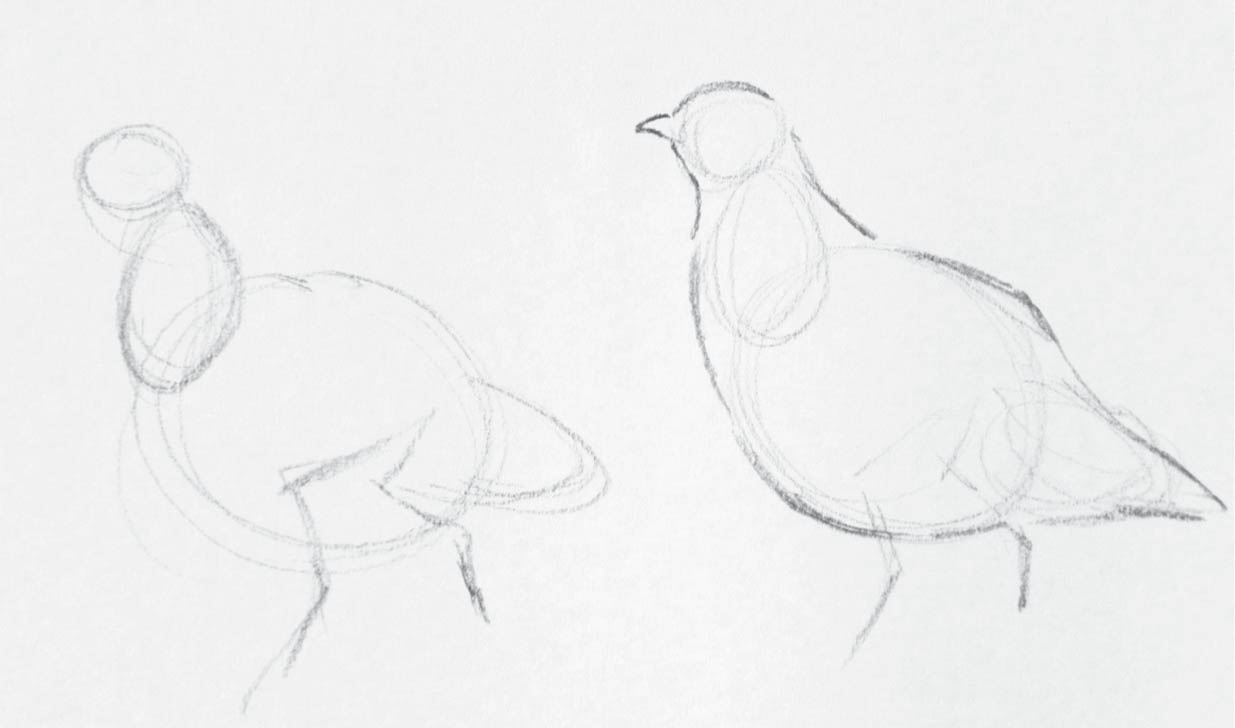

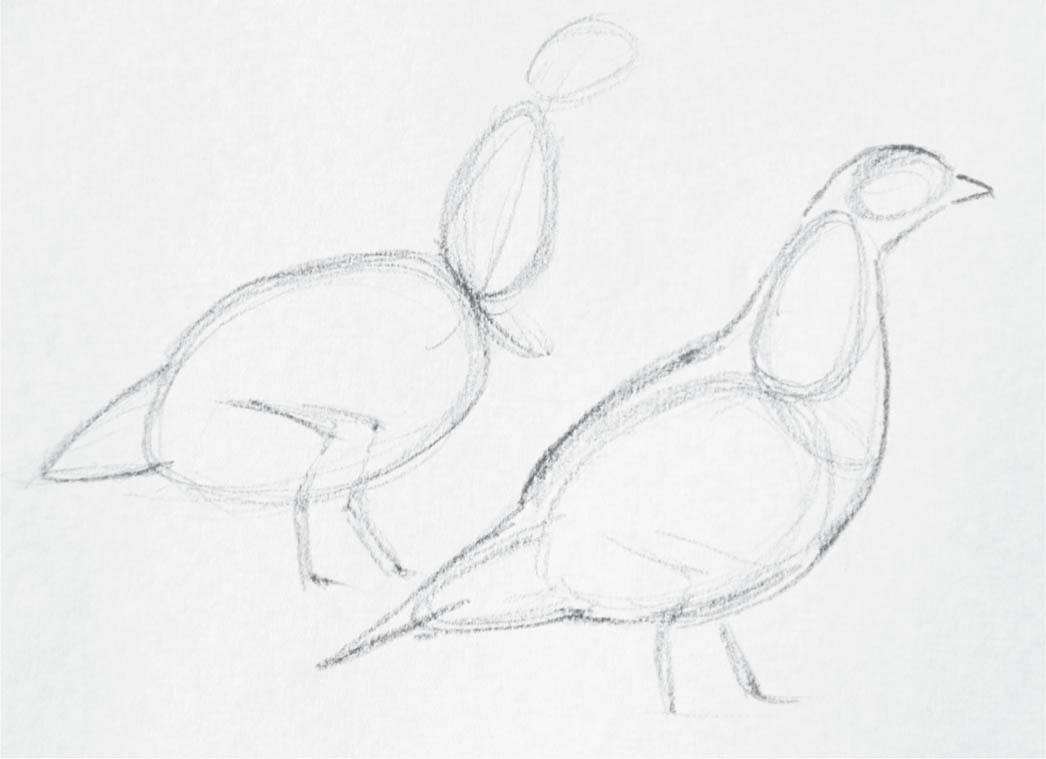

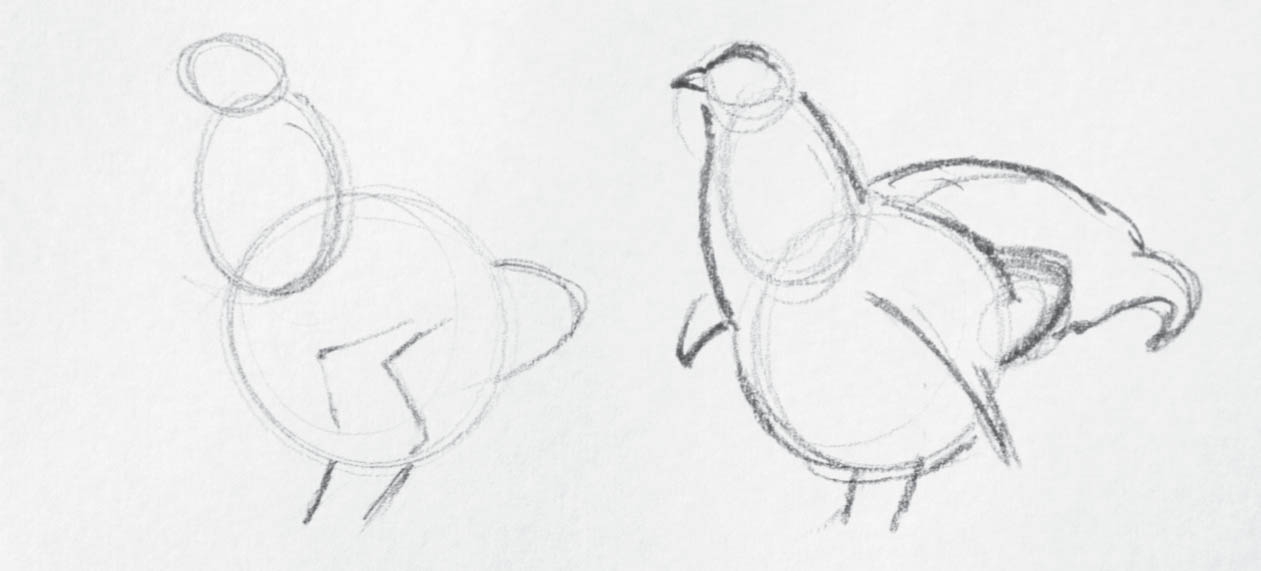

A partridge – construction drawings.

Jonathon Pointer: Sparring with Shadows.

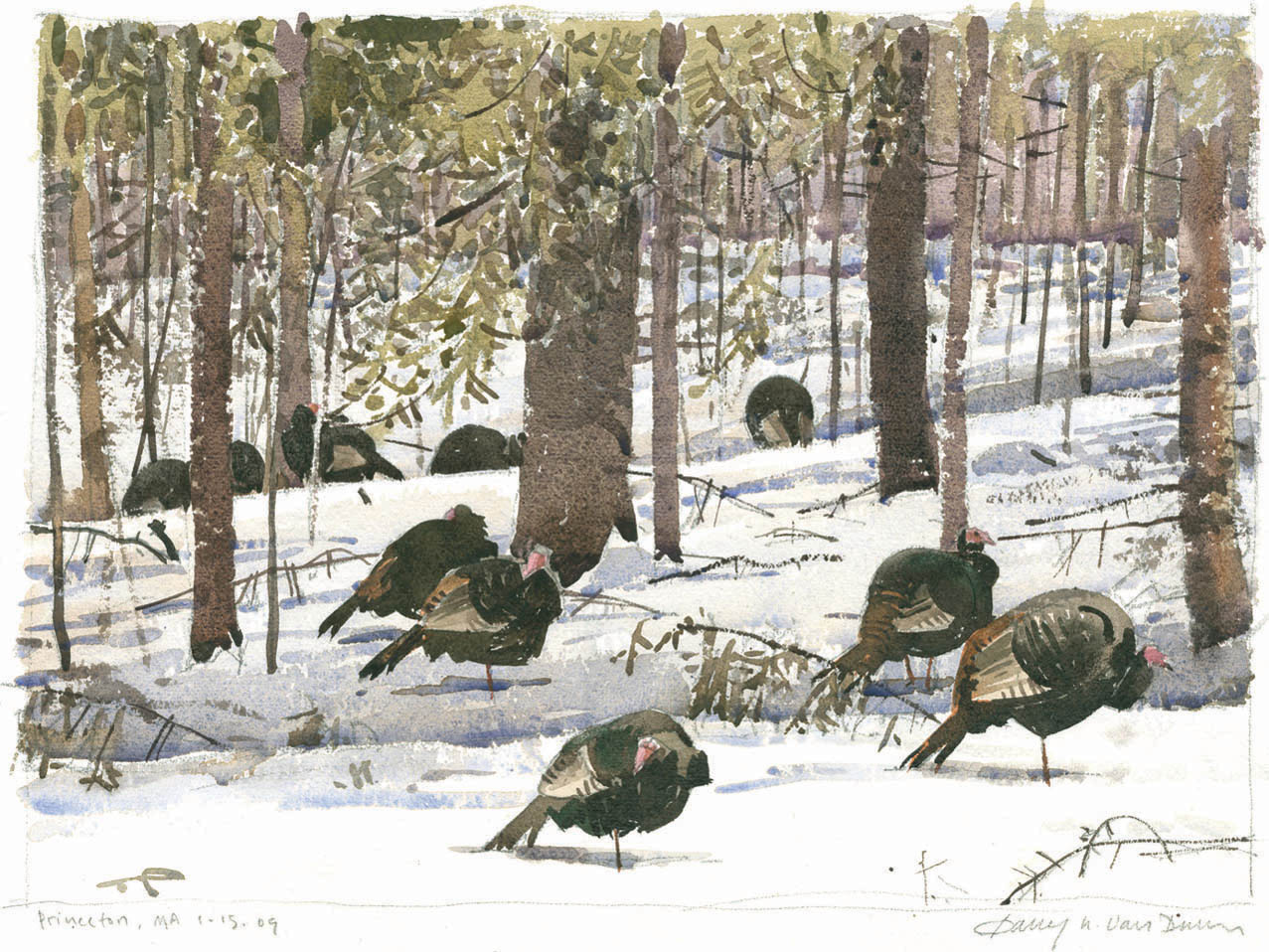

Barry Van Dusen: Wild Turkeys from the Studio.

Tim Wootton: grouse.

Debby Kaspari: wild turkeys.

David Bennet: blackgame lek.

Cormorants and shags are long and cylindrical in body shape with serpentine necks and large wedge-shaped tails. They have broad wings; conspicuous features as they regularly hang them to dry – a typical posture. All four toes are webbed (as in gannets) and their short and powerful legs are used to propel them through the water as they dive frequently for their prey, primarily fish. They have long and fiercely hooked bills, which are excellent for catching and holding fish.

When drawing these forms, particular focus ought to be on the neck and head; the long neck can create some curious shapes when extended and is even more complicated when hunched up. Watch for the point of balance, too: the legs are set well back and they have a most upright stance. Because of the short tarsus (foot) they can look ungainly when perched. They sit low in the water and don’t appear to have the buoyancy of ducks or geese; often there will be just a hump of back showing and the neck periscoping at the front end. They have oily plumage that appears glossy and slick, particularly on the backs and wings.

Paschalis Dougalis: cormorant.

Tim Wootton: cormorant skeleton.

Tim Wootton: shags.

Tim Wootton: juvenile shags.

Tim Wootton: brooding shag.

Szabolcs Kokay: pigmy cormorants.

John Threlfall: cormorant study.

Tim Wootton: diver.

Robert Bateman: Northern Reflections – common loons (great northern divers).

David Bennett: red-throated diver and red-necked phalaropes.

These large, goose-sized birds breed colonially and plunge-dive for their food – fish. Spectacular in the air, everything about them suggests power. They have a very strong sternum and clavicle, partly to support the large muscles required to move a heavy bird through the air and partly because of the impact they receive each time they hit the water. Where they breed they are very easy to observe but their neck contortions and long angular wings can cause even the most attentive draughtsman problems.

A really heavyweight bill and skull are used as a battering ram to break through the water surface; the bill has delicate lines in blue/grey which can make the structure of the bill difficult to understand (it may help to see it as a long wedge). The important characteristic of the gannet’s head is the way the eyes sit on the hard gape of the bill – a dark line continues under and back from this point.

Tim Wootton: gannet skeleton.

Tim Wootton: gannet post-mortem study.

Paul Bartlett: Life on the Bass Rock. Collage and acrylics. A riot of subtle hues and printed paper collaborate in the ‘whites’ of the gannets; fierce eyes and fiercer bills jab at any neighbour who strays.

Tim Wootton: gannets.

John Busby: gannet courtship – heads and wings in all directions, swaying to an unheard rhythm.

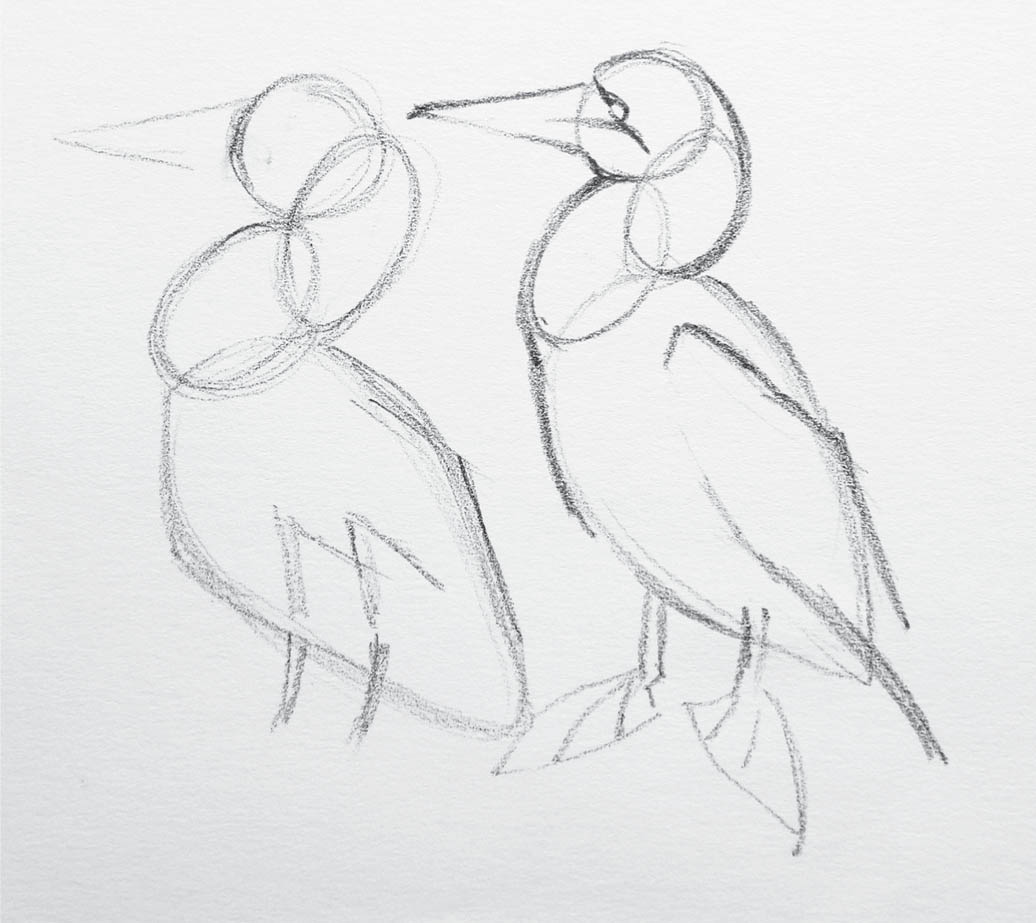

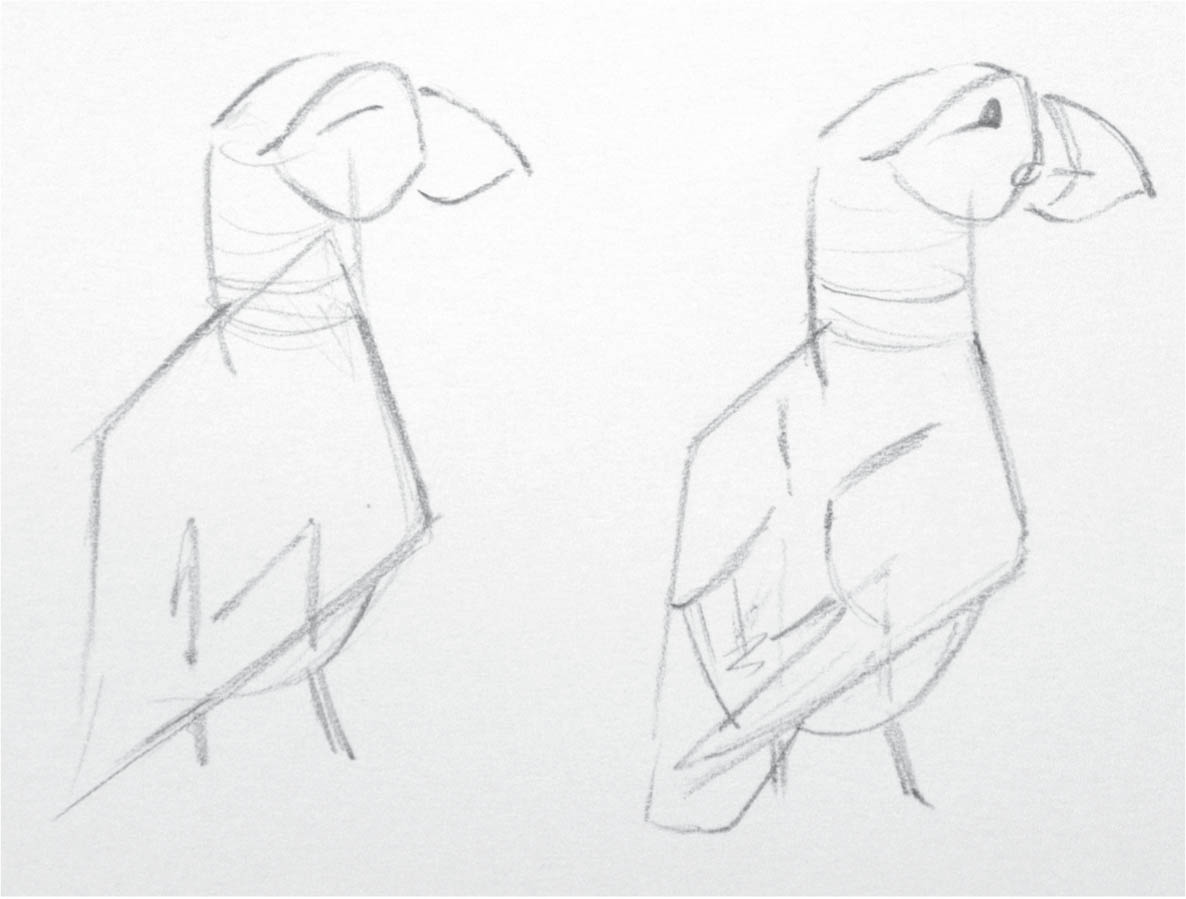

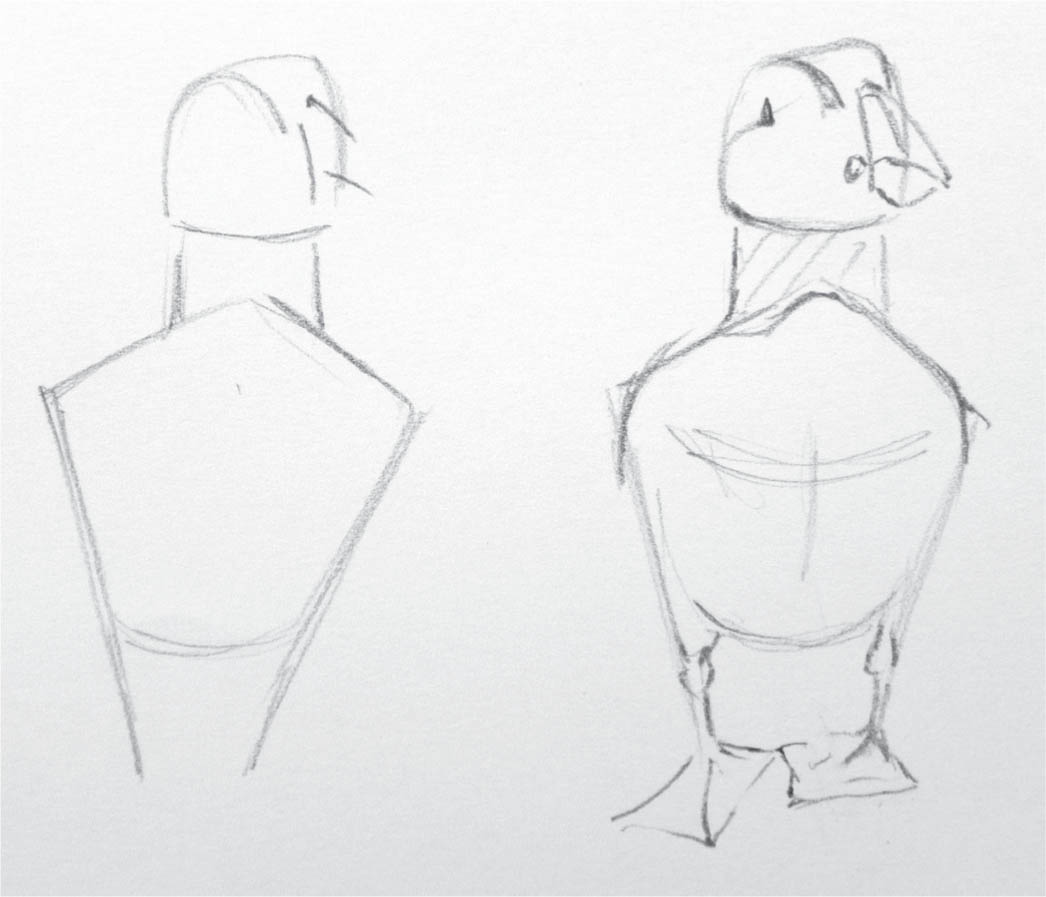

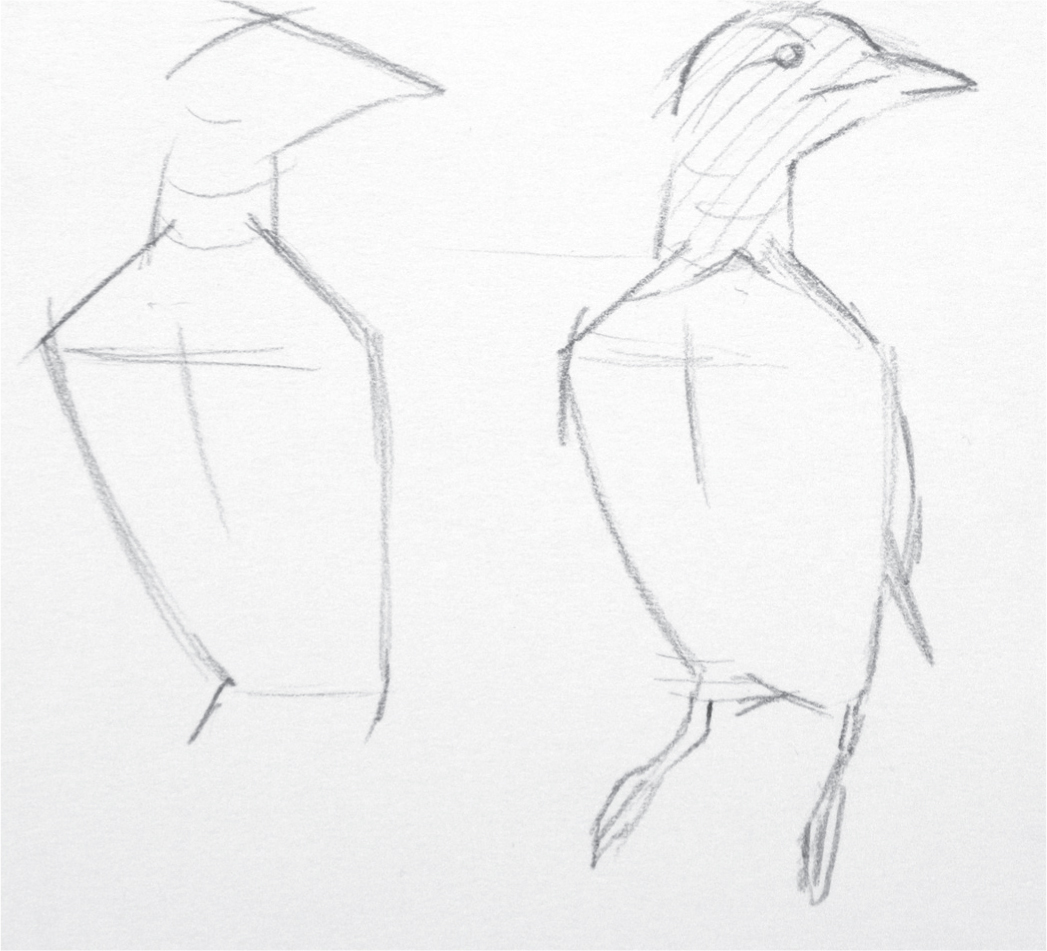

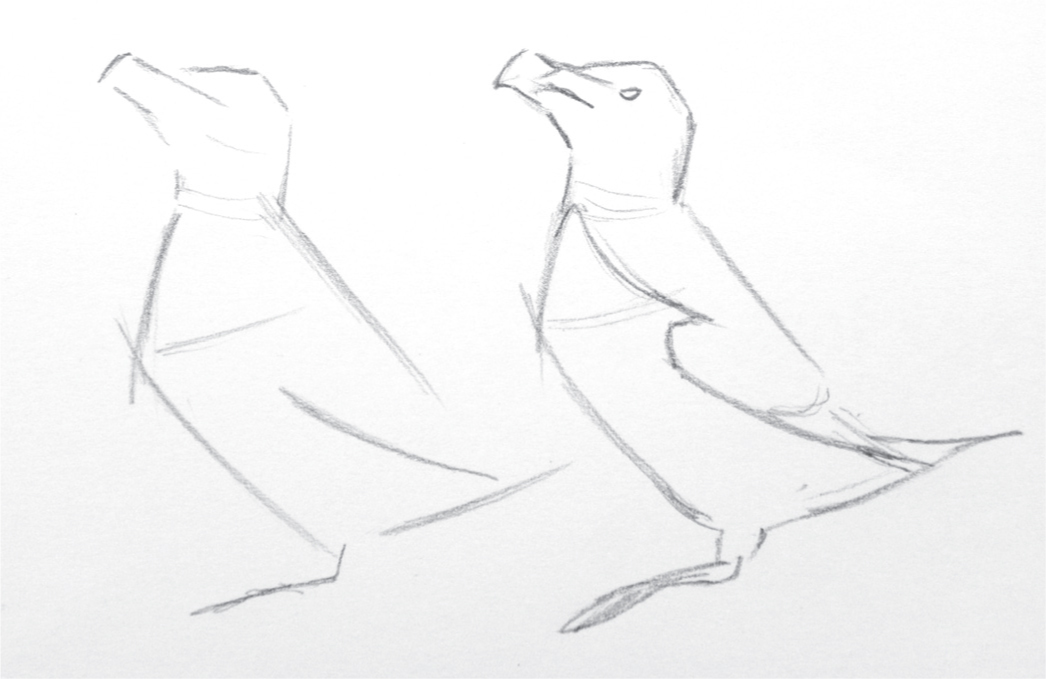

AUKS (PUFFINS, RAZORBILLS AND GUILLEMOTS)

Auks have slim, cylindrical bodies that are wider at the chest, giving them a ‘puffed-out’ appearance. They have short stubby legs and short narrow wings, and are characterized by their upright stance and cliff-nesting habits. They are excellent swimmers and dive to incredible depths for fish – common guillemots were noted by oil-rig divers working in the North Sea at depths of 400 metres and more! A look at their anatomy helps us to understand how this works: they have long and very deep sternums to which very large muscles are attached. This serves two purposes: first, it protects their internal organs in deep water (the pressure would crush them otherwise); and second, because their wings have evolved to be short and narrow – ideal for underwater swimming, but not so good for soaring and gliding. Therefore their method of flight is all action with fast, whirring wings – big muscles are required for this.

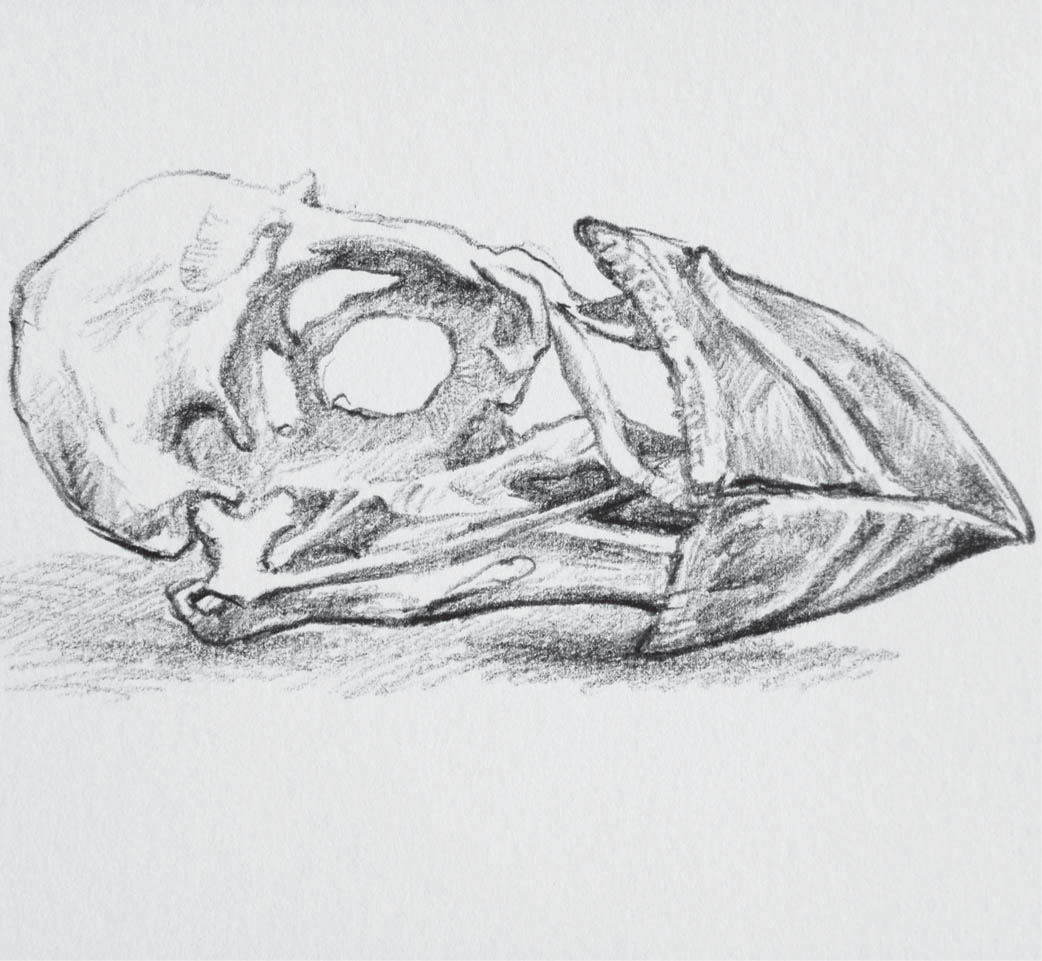

Tim Wootton: puffin skeleton.

Tim Wootton: puffin skeleton. Skull lacking horny sheath and puffin skull with horny sheath in situ.

Tim Wootton: puffins.

Auks tend to sit on their tarsi (the part of the foot below the ‘knee’) and so they shuffle about on the ledges. But they can stand properly on their toes and puffins especially are nimble little things when manoeuvring on land.

Puffins and razorbills (of which the now extinct great auk was one) have a horny sheath to their bills, which is grooved to help in holding sand eels and other small fish.

Tim Wootton: guillemot.

When drawing auks it is worth taking time over getting their bills correct. They have very sleek lines, particularly the guillemots, and ‘tight’ plumage which has a velvety-looking texture when they are dry, the flight feathers being somewhat glossier.

Tim Wootton: razorbill.

Tim Wootton: razorbill.

PARROTS

For many of us, contact with a member of the parrot family is probably a caged bird. They are very intelligent creatures with distinctive characters and if kept as pets can interact closely with their owners. Capturing these birds’ facial expressions would rank highly on any ‘must-do’ list when approaching drawing and painting them. Their ability to ‘talk’ affects the way we perceive them too, influencing the way we might make images of them.

Many species are colourful with decorative plumes and splendid tail feathers. They typically have large heads with proportionately hefty bills, used for breaking open nuts and seeds and for eating fruits. Some species are predatory. As with owls, the arrangement of their eyes and large bill gives rise to slightly comical expressions.

Frank Van Boxtel: Kiwi Citron (crested cockatoo).

Tim Wootton: skeleton of a parrot.

WADERS

Wading birds are found the world over and generally have long legs and longish bills (although some of the plovers are shorter in the bill). They tend to probe soil, sand and mud for worms, invertebrates and crustaceans. As ‘types’ wading birds could include flamingos, herons, storks and cranes, curlews, godwits and oystercatchers down to the little plovers, stints and sandpipers. Most waders have nidifugous young – chicks that are able to disperse from the nest almost immediately after hatching.

A familiar ‘type’ of wader is the oystercatcher, found as various species across North America through Europe and into Australasia. They are powerfully built medium-sized birds with long, thick bills, used to pick whelks and snails from crevices and to hammer through heavy mollusc shells.

Because they spend much of their lives foraging for food items amongst rocks or in shallow water, drawing oystercatchers means the artist has to look for points of balance when drawing these (and other) waders. Most waders have an almost teardrop-shaped body, tapering to their wing tips with relatively long legs and necks, which make them amongst the most elegant of birds.

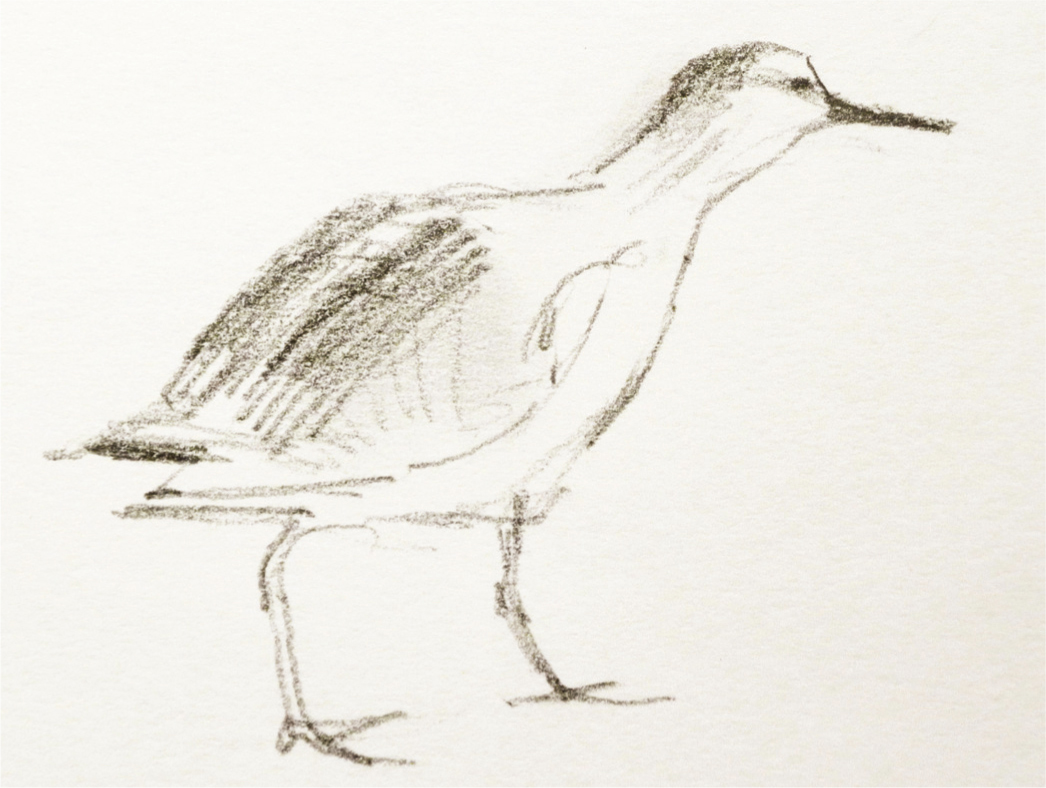

Tim Wootton: redshanks.

Tim Wootton: curlew.

Tim Wootton: curlew in flight.

Jonathan Pointer: snipe and butterbur.

CORVIDS

Members of the crow family are found almost everywhere and as well as being famously intelligent are also quite easy to approach and study. Rooks especially can be compliant models, particularly in early spring when they are refurbishing their colonial nests at the ‘rookery’. Crows are long-lived and are faithful to nesting sites; most crows will use traditional nest sites, re-using the same site and in some cases the same nest year after year. This aspect of their behaviour is sometimes reflected in place names that relate to their presence in an area. It also means that locating them for the purposes of study is fairly easy.

They are the largest of the ‘passerines’ (perching birds) and although typically represented by black birds, the family also has some of the most strikingly patterned and colourful members too. They are recognized as being symbolic of evil and death, occurring in literature and film from Shakespeare to The Omen and The Birds.

They have thick and powerful bills, large heads and a deep-bodied appearance, partly due to having ‘boots’ (heavily feathered legs). Rooks in particular can have a triangular appearance.

Tim Wootton: skeleton of a rook.

Juan Varela: studies of ravens. (First published in Entre Mar y Tierra/Between Sea and Land, Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.)

Nick Derry: rook.

Beth Rosenkoetter: crow.

Tim Wootton: rooks.

Tim Wootton: hooded crow.

EAGLES AND OTHER LARGE BIRDS OF PREY

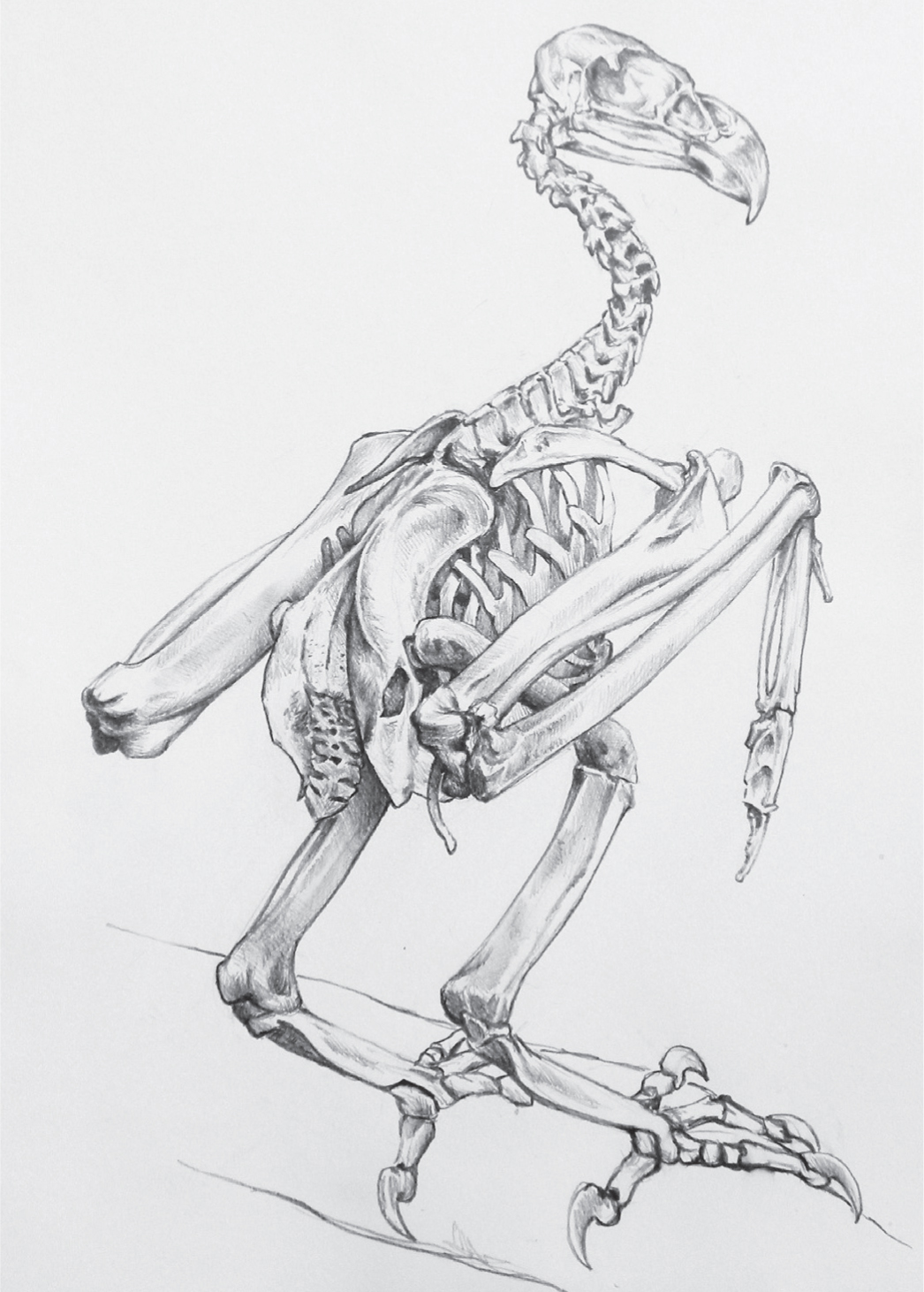

The skeleton of an eagle tells much about its way of life. Immense wing bones and an extremely strong backbone reveal its aerial prowess but it may come as something of a surprise to see the enormous leg bones. Of course they need strong legs to hold up a heavy body, but that doesn’t explain these massive structures. To do that, we need to consider what these birds feed on and how they go about catching their food.

The skeleton illustrated is that of a white-tailed sea eagle, a bird with an enormous wingspan (often described as a ‘flying barn door’ when seen in the field). They feed on fish and seabirds which they catch on the water surface. Other eagles feed on mammals such as rabbits, small deer and even monkeys, some on snakes and lizards and other birds. What they have in common is that they generally catch their prey following a high-speed pursuit, hitting their target with their ferociously armed feet. The impact is violent and the eagle needs powerful legs and feet, both to make the catch and to withstand the impact.

Tim Wootton: skeleton of a white-tailed eagle.

Juan Varela: booted eagle.

Andrew Ellis: golden eagle being mobbed by a merlin pair.

They have wickedly hooked bills ideally adapted to ripping flesh, and fierce eyes with excellent vision with which to locate their prey. Any rendition having an eagle as the subject will need to suggest great bulk and power and catch the facial expression correctly. The eyes are deep-set and are browed heavily, emphasizing the piercing look. There are also areas of coloured bare skin around the eyes and bill, a feature common in most birds of prey.

In flight they have distinctive primary feathers referred to as ‘fingers’, the arrangement of which can aid identification. Forms in this group include eagles, vultures, large buzzards and other hawks.

HAWKS AND FALCONS

Although in ornithological terms hawks and falcons have many differences, for the sake of identifying the salient features they can be grouped together.

They show the classic body shape of the avian predator: they have a teardrop-shaped body and are powerfully built across the shoulders.

These birds are all about speed and agility and amongst their number are the fastest creatures on earth. Their wings are visible at rest; indeed much of these birds’ anatomical features are well defined. Because of the popularity of falconry, good views of these otherwise elusive birds are readily available at places such as country parks, stately homes and other specialist collections and aviaries. The structure of their wings is revealed at feeding time. The birds habitually hold their wings over their food, in effect cloaking it (an action called ‘mantling’) when the angles of each wing joint can be deciphered quite well.

In flight birds of prey show good definition and distinctive profiles (a profile drawing would be a good point at which to start). Even though they are incredibly fast when pursuing prey, some species are easy to watch and sketch even in the wild. Buzzards (hawks in the USA) are locally common birds and their habit of perching on telegraph poles, fence posts and in some cases molehills as they wait for feeding opportunities make them compliant models for the artist. In flight they soar and will also hover from time to time; actions that are beautiful to watch and fruitful to draw.

Tim Wootton: skeleton of a sparrowhawk.

This is just a very small proportion of the subjects available but I wanted to highlight types that are easy to locate and are easily viewed. With experience and confidence you will soon be seeking out your own models in the natural environment. And once you are happy that you are catching the general look of your birds, you may then start to delve a little deeper into their lives and their characteristics.

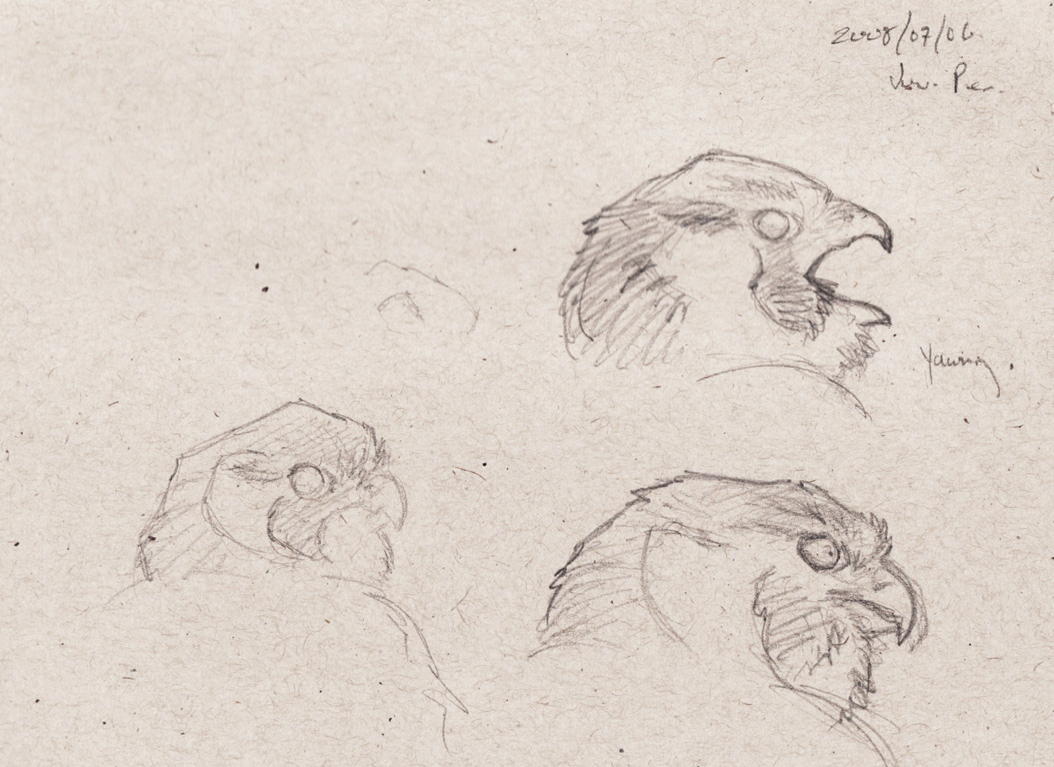

Jocelyn Oudesluys: peregrine studies.

Szabolcs Kokay: saker falcon.

Andrew Ellis: Confusion Tactics – sparrowhawk and bramblings. Acrylic on panel.