Tim Wootton: Light-flood: Eider Pair.

ADVANCED TECHNIQUES

It doesn’t make much difference how the paint is put on as long as something has been said. Technique is just a means of arriving at a statement.

Jackson Pollock

Technique is noticed most markedly in those who have not mastered it.

Leon Trotsky

One of the great challenges to you as an artist will be ‘how to realize your vision’. Regardless of philosophical ideals, there are many ways to approach the making of two-dimensional art: painting in oils, acrylics, gouache and watercolour and several recently developed media with interesting properties; drawing in ink, pastel, charcoal, oilsticks or graphite; mono printing and lino/woodcutting and etching, collage and all manner of combinations of the above which could be loosely grouped as ‘mixed media’. For the purposes of this book, we’ll try to keep focused on what could be termed the traditional methods of painting and drawing. There is a great deal of information available on the other processes and some or all may be perfect for the portrayal of birds in the capable hands of those with curious minds.

Some painting processes are very time- and labour-intensive, whereas others are instantaneous and expressive and the piece can be completed alla prima (in one sitting).

Painting grisaille is a process where the main values (tones) of the painting are rendered, traditionally in greys but in practice in any muted colour (sepia being a favourite of mine). Sometimes even a toned-down version of the final colour scheme is used.

The following are a few insights into the working methods of wildlife artists.

PAINTING IN ACRYLICS

ABOVE THE RAPIDS – GULLS AND GRIZZLY

Robert Bateman describes the journey of the Pacific salmon:

Pacific salmon form an important part of the many bounties of North America’s wild west coast. We all know the epic story of birth in a clear and beautiful mountain stream, the growth of the fingerlings, the journey to the sea, the mysterious years in the deep, distant ocean, then the mass migration back to the place of their birth as handsome, gleaming adults. Then there is the heroic struggle against the current, leaping waterfalls and avoiding capture to the final destiny of courtship, mating and death. The story is almost biblical in its scope.

The salmon is really responsible for the possibility of the great west coast aboriginal nations with their highly evolved cultures. It was an important item in the European settlers’ diet, then later in trade and commerce. And now we know of the health benefits of the Omega 3 fats and oils in salmon. Recently there have been sinister discoveries of too high mercury levels. Now many knowledgeable people tell us of the threat that salmon farming is having on this precious wild heritage.

Robert Bateman: Above the Rapids – Gulls and Grizzly. 30 × 48in, acrylic on canvas, 2004.

Salmon, of course, are an essential element for nourishment for wildlife from grizzly bears, to birds, to other aquatic life and insects. Moreover, scientists have just discovered that the nutrients make their way through bears, birds and insects to fertilize the giant west coast lowland forest. Salmon rivers have much bigger trees than non-salmon rivers. This fish is so important and integral to society and nature that many people think it should be the poster creature for the Endangered Species Act instead of the spotted owl.

Although I have not shown a salmon in this painting, you know that they are there. Some are in the quiet water above the falls and others are still fighting their way upstream. This is why the grizzly bear and gulls are there. This is the banquet time so important to these species and many others. It is a far-ranging crime against nature and against ourselves to jeopardize the spectacular wild salmon.

Robert Bateman

First and foremost is the idea or the thought behind the painting. Although it is a joy to create something just for the sake of creating, it is much more satisfying to create something special. It may not necessarily be brilliantly executed, but ‘special’ means it comes from the heart and experience unique to you.

One definition of a masterpiece I have heard… ‘when you see it, you should feel you are seeing for the first time, and it should look as if it is done without effort.’ This is a very, very tough yardstick. I wouldn’t say that I’ve ever done a masterpiece, but when I am struggling with each painting – and they are all a struggle – I often feel that I am nowhere near those two goals.

I take pictures of bits of habitats that I find appealing. I dislike front light, i.e. the sun behind the camera, and always choose back light or side light, or diffuse light as in a cloudy day. I love mist because it describes the volume of air between the objects. I also visit zoos and wildlife or waterfowl parks. In using these as photo reference, you must know what happens to captive creatures. Most cats get big bellies, birds often have their primary feathers clipped. Even though one visits the same zoo over and over, there are always surprises of lighting and pose and many other unpredictable factors.

I try not to have parts of the picture fighting for dominance; either the habitat or the animal takes precedence, but not both.

I start with little sketches in pencil about the size of playing cards. I may do one or two or ten until I get the right composition. Since I was an abstract painter in my late twenties and early thirties, I can see the simplified shapes –or abstract qualities – on this small crude scale.

Most often I start right in with a medium paintbrush and a medium dark colour as if I am doing a monochrome, thin watercolour. I rough in the whole composition, including large area washes. Next I go over it all again with slightly lighter tones mixing white with the colours. Then I paint light strokes and highlights, often using white with a bit of yellow ochre. I use a limited palette of colour to harmonize in each picture.

I usually mix some white even with my darker colours to make them semi-opaque from the start. The painting progresses this way, starting out looser and bolder and gradually getting finer and more detailed, light on dark, dark on light, and so on.

For special subjects like bright flowers or birds, I have colours in lesser amounts in tubes: cadmium red light, cadmium yellow light, phthalo rose and phthalo blue or Prussian blue. Each tube lasts me several years.

I use artificial sable brushes of a variety of makes, riggers for fine lines and old worn ones for dry brush effects. For larger areas I use hog’s hair brushes or even house paintbrushes. People often ask how long it takes me to do a painting. The answer is, I don’t know. I work on five to fifteen at once. I like them when I first start them, then they always get worse so I start a new one to cheer me up. By the time the fifth one looks really awful to me, the first one doesn’t look quite as bad, and a new idea about it may have come along so I can work on it for a while. One took me about six years off and on!

Sometimes I have part of the [photograph] that I can’t see well enlarged on the computer and brightened so that I can see it better. Of course, this copying of the photo does not go on all the time; I start to take liberties by changing things, eliminating things, playing with light and shade, etc. Towards the end, it may not look like the photos at all. I could never understand why some artists shrank from using photographs. Everybody uses photographs if they are at all interested in realism. [But] if you have a subject that does not change much and you are able to work in the field, it can be a wonderful alternative to photography. The real thing is great and has the added benefit of being out in nature with the smells, sounds, and general fresh ambience. The point is still the same – good reference for your painting – whether in the field or from photos.

The sense of space is shown by air. And air neutralizes tone and colour. The further away, the paler the darks and the duller the light areas appear. To create my misty effects I use a foam rubber sponge with a thin wash of white, sometimes adding a bit of raw umber or Payne’s grey or yellow ochre depending on whether there is mist or dust, etc. I pat it until dry. When a paler colour is put over dark, it always looks dead purplish, so I paint it paler than it will end up, then bring it back to life with a very thin, darker wash.

You must not be a slave to the colour or tone of the creature. Bald eagles have more or less white heads and black wings but the highlighted parts will be paler and the shaded parts will be darker than the actual colour of a flat skin. I have shown an eagle with a charcoal throat that is darker than the highlights on the wing. All parts of the painting should have consistent light and shadow including the creature and the habitat. For a given angle of surface, the light and tone would be the same. Therefore if a surface is at a different angle, the tone will be different.

GENTOO PENGUIN

The artist describes the background to the painting:

I saw this scene take place in Antarctica. Two giant petrels were attacking an albino Gentoo penguin. I should not admit it but giant petrels are among my favourite birds. Their ugly faces are actually quite interesting to draw or paint. At any rate they made suitable villains for this piece since they were picking on this particular penguin because it was different. It is in a way a comment on racism and bullying. This story did have a happy ending. The little penguin courageously continued to fight them off and they eventually gave up.

Robert Bateman: Gentoo Penguin. 20 × 48in, acrylic on canvas.

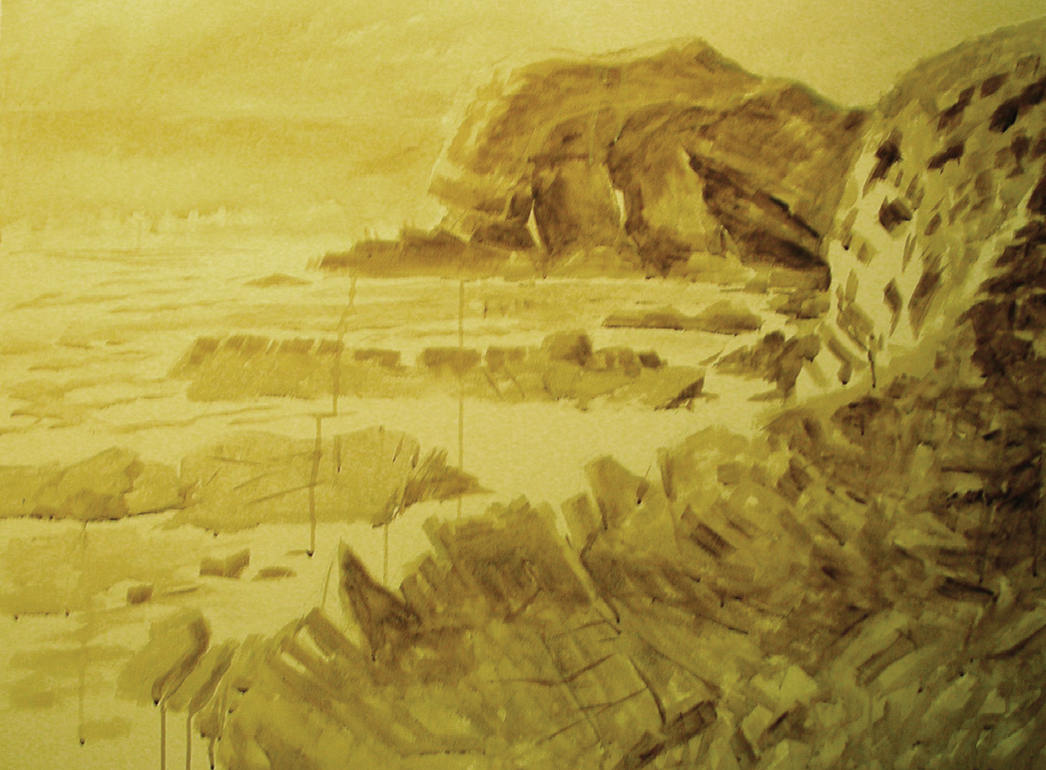

This painting of Harraborough Head in Orkney is painted using the grisaille method. The headland is very distinctive and I wanted to keep faithful to that but I also wanted to introduce very dramatic lighting to give the piece an ‘edge of the world’ flavour. The fulmars are symbolic of that transition between ocean and land.

Tim Wootton: Harraborough Head and Fulmars.

The first image shows the sepia monochrome grisaille under-painting. I kept the paint quite thin and built up the depth of value by adding more layers of thin paint, regularly rubbing areas of paint away with a rough cloth. All of the canvas is covered with at least some paint, lowering the key of the painting.

The second image shows the blocking in of the hues and how the colours relate to the underlying values. The heavier paint and deeper hues start to emphasize the shadow areas whilst there are still zones of light under-painting exposed to keep the balance.

The finished work has warm pinky-gold hues laid over the highlighted parts where the low setting sun catches the face of the rocks. Similar rim-lighting (just the outer edges of the object are lit, the rest in shadow) is employed on the nearest bird and slightly more understated tones deeper into the picture.

Paul Hawkyard

As a support I use MDF board. This is gessoed both sides to stop the board warping. The side I am working on takes four to five coats of gesso with a light sanding after the last coat. This gives me a fairly smooth surface to work on. I then transfer my prepared drawing onto the board and fill in the rest of the composition very lightly in pencil. The reference photograph was taken in the aviary. I mask off the image of the bird using masking film and use an airbrush to paint the background. I deliberately spray the background to make it look out of focus as I want the attention to be centred on the bird. I finish off with a couple of coats of titanium white to subdue the colours.

I remove the masking to start work on the bird. Using very watered down ultramarine blue I cover the entire image of the bird, except for the feet, cere, beak and eye. This seals in the pencil lines and gives me an overall colour that will ultimately shine through the over-painting. I then mix a mauve colour using ultramarine and brick red to glaze over the head. My next step is to work on the eye which helps to bring the painting to life, ensuring I capture the highlights in the eye accurately. These are often more than just a white dot in the pupil and consist of different shades and reflections. The shadow from the brow is painted in transparent layers forming a translucent effect. I then add the drop shadows for the feathering on the head and proceed to fill in the detail.

Paul Hawkyard: Chilean Blue Eagle.

On completing the head I start to work down the body. Mixing various shades of blue, I paint the feathers one at a time, edging them and adding some detail with titanium white and blue glazing to soften the brightness of the white. I add shadows to the next feather down and continue on down the body. Some of the feathers are a mauve colour. I mix various shades and work on the feathers in the same way. I use burnt umber and ultramarine blue to mix a dark/black to strengthen the shadows.

At this point painting feathers becomes very tedious and so I decide to address the foreground landscape; I under-paint the whole of the background using the same mauve as on the feathers, which helps to harmonize the piece. Once dry, using a knife and an impasto technique I scrape on titanium white and then remove from some areas – that adds shape and shadow to the snow. While the paint’s still wet I scrape out areas where the rock face shows through. I add light shadows under the thick paint that represents the snow. Again using the same colours as the bird’s plumage I paint the rock face. Once this is dry I use a natural sponge to give the rocks some texture. I use a mixture of sap green for the grass, changing the hues by adding blues and yellows. I paint these quite thickly and then I add more purple shadows in the snow. After this welcome break, I’m ready to take on more feather work!

I continue round the body as before and sketch in the missing part of the composition: the rabbit. I originally wanted to paint this bird in its typical pose sitting in a tree, clutching a snake. However, as the bird was used for falconry purposes, the client requested it was painted with the humble rabbit. The rabbit is undercoated with raw sienna. The shadows that indicate the undulation of the fur are painted in quite dark using burnt umber and ultramarine. Using raw umber I roughly paint in the fur, being mindful of the direction it grows. I mark out the tips of the fur in titanium white, finishing with glazes of raw sienna, raw umber and burnt sienna. When I paint hawks’ feet I am always aware they are the most formidable part of the bird raptor. Using a very small brush, I paint every scale. I’m slightly apprehensive when it comes to painting the blood; however I felt it added to the drama of the piece.

To finish I add some dead grasses. Then poured a gin and tonic and called it a day!

PAINTING IN OILS

Jonathan Pointer

Inspiration always comes from nature itself but my type of painting, due to the length of time spent on a canvas and attention to realism, means I only paint in the studio. Field trips, however, are a vital element in my work. I have to see the subject matter I’m painting and its environment to understand how to convincingly recreate it in paint and of course gain inspiration to initially spark the creation of a painting.

On field trips I try and immerse myself watching the subject and gathering reference for the different elements of the painting, therefore I spend a lot of time with a camera, photographing interesting plants, rocks and how light affects these and the animal or bird in different interesting poses.

I never work from just one photograph. To replicate a photograph to the point where foreground and background is blurred as in a photograph I feel is a pointless exercise. I often have a preconceived idea of what I would like to paint and then gather the photographs for that painting to flesh out the idea and allow me to paint with the kind of realism I cannot get from field sketching. A large painting with lots going on will use dozens of different photos which I pull together in the piece.

I try and keep my painting technique as simple as possible. I use oil paints both for the wonderful richness of colour and because they are so versatile; used thinly creating a smooth surface, or an impasto way creating a chunkier, rougher surface ideal for earth or rock. I paint on canvas which is gessoed with three or four coats then sanded. Gesso can be applied with a variety of textures depending on final technique. When the painting is varnished, the initial gesso texture is more apparent and I believe adds something to the surface of the painting, preferable to uniform textured weave which can distract the eye.

Jonathan Pointer: Signs of Spring.

I paint with sizes 2 to 8 watercolour brushes for my oil paints. Because my work is intricate, I find the greater flexibility of this brush delivers the paint more smoothly to the canvas than the stiffer, less flexible hog’s hair brushes often associated with oil painting. Larges brushes are sometimes used for blocking in big areas.

I first start by drawing out the key elements of my picture onto the canvas with a medium soft pencil, this allows me an early indication that all is well with composition, proportions and the idea itself before I commit weeks or months of effort to the painting.

I apply mid tones selectively: green mid tone for grass or vegetation, brown mid tones for earth etc. Then I’ll begin applying the detail; I paint what interests me most rather than painting backgrounds before foregrounds. By painting my favourite bits first, I reason I’ll try extra hard on the less inviting, more laborious elements in the painting for fear of ruining the good bits!

Gather a group of artists in a room and ask them their technique in how to varnish a painting the right way and you are guaranteed a debate! I know some artists who swear by spray varnishes and others who heat their varnish before applying it to the painting. I always varnish my paintings, usually three or four times with liquid varnish that is applied with a large, clean, flat-headed brush. When the varnish is uniformly transparent over the whole, I know that the painting is complete. If you examine your painting from a low angle using a handy light source you can see if the varnish is evenly applied.

I spend months on individual paintings. I’m not a slow painter, but being interested in all the elements of nature means that I devote as much time to painting plants, leaf litter and rocks. I’m often asked how I have the patience for such long stints on a single painting. Well I have a lot more patience now than when I first started. So patience is in part learned, like technique, but it is true that those paintings that take months can grind me down. To stop this happening I usually have several paintings on the easel at any one time. When I feel my concentration is slipping I can move onto a new painting for a time before returning refreshed to the larger painting.

Mark Andrews

This Asian rainforest denizen is one of the most incredible birds I’ve ever seen, the eyebrow glows like fire in the forest gloom. It’s a bird I just had to paint and felt oils were the best way to convey the staggering vivid colours of the bird I saw – a little bundle of magic!

Mark Andrews: banded pitta. Oil on panel; initial sketch and wash.

Adding depth: to keep the energy in the painting the artist moves across the painting, working on different areas simultaneously. This approach also helps to keep the balance in the piece.

Besides being a wildlife artist Mark is a photographer and an Ecological Tour Leader and has been fortunate to visit many special and exotic locations. Photographs are invaluable for habitat reference and he takes many pictures on his trips when time with clients doesn’t allow much opportunity for some trad itional sketching. A few quick preliminary sketches are made to get the balance of the picture and then he’s straight into the painting. The image is lightly sketched onto the canvas using pencil and charcoal and then the drawing is accentuated using a thin wash of oil paint diluted with white spirit. At this stage a few tones are introduced to set the overall value balance and to aid navigating the piece.

Building levels: at this stage the darkest areas are intensified, which emphasizes the sunlit patches.

Mark Andrews: banded pitta. Oil on canvas. The final stage includes detailing the bird: working on that incredible eyestripe, the ‘firebrow’, painting the bands across the bird’s breast and adding extra highlights to fine-tune the balance.

The dark forest and leaf litter is always a challenge for me and in this case the eye was most certainly drawn to the bird’s remarkable pattern. My vision of this painting had softer detail around the bird as the vegetation merges and entwines around it. Working loosely, this approach helps me to keep the balance in the piece and helps me focus on the areas that are missing, the jump from the image in the mind to the piece on canvas.

I need to bring the bird out a little more, and add some depth and distance to the rear; the leaf litter shadows are added to with highlights of mauves, blues and pinks to balance, colours I often see with half-closed eyes when working in rainforests, and ones which complement the focal point.

Because of the nature of the environment where these birds are found, it can be pretty dark on the forest floor so some of the highlights are where shafts of light percolate through and others are reflected light. The bird is also being softly lit by reflected light on its underside, something you often see on terrestrial forest birds creating a slight ‘aura’, enhancing the observation and the experience, something I was keen to portray here.

THE PROCESS OF MAKING PICTURES

Darren Woodhead

As an artist, I have and always will work outside in the field. I find this is the only way that I can work. Whilst growing up it was hard to find paintings that kept the life of what I saw as a young naturalist, so many images were lifeless and staged. But I found myself looking at paintings and drawings from artists such as Eric Ennion, Charles Tunnicliffe and more recently John Busby and David Measures that encompassed the energy of the moving object and challenged the early works that I found lacking. It seemed so natural and easy, deep in every line and every mark of the drawings, the one thing that stood out was the knowledge and confidence the artists had with their subjects. There was also a sense of honesty that I found captivating.

Working outside obviously has its pitfalls. There is no time for deliberation and worry, any image has to happen speedily and instinctively. Nothing ever stays for a specific length of time and subjects are always moving or going about their daily lives with an eventual disregard for the figure nearby. Never do birds or animals stand on plinths and pose as we should like them to do. They are concentrating on feeding, migrating, resting and surviving. It would be a shame if they did pose for us. That excitement and essence that makes seeing something that we do not normally see, special, would be lost. I am of the view that however we are lucky enough to see animals or natural history, then surely this is the way they should be described and scripted. This feeling for the continual world going on around, together with the life and energy they exude, is what I would like my paintings to show and communicate.

I find that the greatest results come from a state of mind which is totally absorbed in work, when I am working without much thinking.

I carry a folder full of varying sheets of paper so that I’m never too concerned about the amount I use, therefore trying to encourage that freedom of thought and expression that will allow results to flow and materialize. For me becoming zoned into the atmosphere is part of the experience. I similarly find it amazing how one can be lost in a painting yet somehow intuitively aware of the goings on around. No doubt I miss so much but how often do I seem to just look up at the right moment to see a peregrine chasing thrushes above or roe deer tiptoeing through the undergrowth below; this always astounds me. Perhaps there is a certain state of mind that is open to what is happening around or perhaps it is just coincidence, whatever the cause these events have made so many days. As mentioned before, I never pass over the opportunity on to include these events as part of the image.

Extract from Up River, The Song of the Esk (Birlinn 2009).

Juan Varela

Much of my work is done on site, using a spotting scope and binoculars. I have developed some memorizing skills that prove to be very helpful when drawing animals in motion; this and the ability to draw very quickly are my main tools to produce reliable bird sketches.

Unless I find some unexpected motif that may put me to work quickly, I usually sit near a convenient spot – a pond, a shore or any bird-frequented place – and wait to see what happens. I normally start by hand warming exercises like making quick contour lines or parts of the animals I see, filling some pages of the sketchbook before I get in that ‘special mood’ when you forget about cold, mosquitoes, pebbles under your rear or whatever. Nothing else matters except the drawing which then starts to become almost automatic. I used to say to my art students that the distance from your sight to your hand through your brain is called ‘fear of mistakes’ – the longer the distance the more the mistakes.

Juan Varela: black kite and coot. Field painting. (First published in Entre Mar y Tierra/Between Sea and Land, Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.)

The painting process is different from drawing in nature. I obviously try to give my best when I’m painting, but I’m more interested in the process itself than in the final result as it’s during the actual process that you learn and discover new ways for your art. When you show your finished paintings you are giving away the end of the process, but nothing (or little) of the struggle it contains may be apparent to the audience. That’s why I like very much field sketches and unfinished pictures – I like to see the processes of the artist. Well-elaborated paintings have more appeal for the clients and audience, but sometimes hide a lot of eraser work. I never use an eraser on my sketch book: what it is a mistake to my eyes today could be a happy finding tomorrow.

Nick Derry

I liken the processes involved in creating a picture as a way of leaving a starting point and heading towards an unknown destination. Many paths are available, shortcuts to be found, fascinating and surprising diversions to explore and the end of the journey is neither always clear nor easy to find.

The starting point is simple, I see something I like in nature, something that inspires, and I sketch it. From there onwards the ‘journey’ is open. Sometimes the sketches need only be remade on a larger scale and other times the sketches are just individual visual elements from the day, seen separately and needing to be knitted together into a composition.

Once a vague picture is in my head, I can start on my voyage. Often I find there are certain qualities – light, environment, colours or whatever, that attracted me to sketch the event I saw which then affect the methods I use in making the picture. Using mixed media can often make for difficult decisions regarding what to use where, but certain media have advantages in creating certain effects. For instance watercolour creates superb light effects, wax can help create textures, especially when acrylic is applied over it and scraped back; collage can be applied to form a whole new surface to work on even when halfway through a piece, and all media, if poorly applied or overused, can completely ruin a picture.

Nick Derry: dunnock and rock buntings (acrylics and collage).

My pictures, as I’m starting to discover, are all about the processes involved; enjoying the journey and discovering where I end up – it’s rarely the place I expected to finish! Sometimes I’ll work hard to get a picture to look a certain way, only to find it ultimately disappointing, so I’ll slap on some more paper to cover the bits I don’t like, or I’ll wash off as much colour as possible under the shower and start again. It’s true to say that I don’t consider the materials as particularly important or valuable in the sense that I’m happy to rework any aspect of a piece, even if it may look ‘finished’. The amount of detail or quantity of time spent on a picture is irrelevant as far as I’m concerned; a painting’s finished when I have nothing meaningful to add to it. And to use the same analogy, if I don’t like the destination, I jump back in the car and go somewhere else. Who knows what’s around the next corner?

So, there you have it – and it just goes to show;

‘There’s only ONE way of Life; and that’s YOUR OWN!

The Levellers

Nick Derry: Hoopoes and Light (watercolour).