The classic definition of generation in modern conversation is “birth cohorts; people born between a certain year and another certain year.”

Using this classic definition of generation, a glance online will tell you that baby boomers are considered those people born between 1946 and 1964.

Gen-Xers were born either between 1965 and 1976, between 1965 and 1980, or between 1961 and 1981, depending on who is talking.

Millennials (also called generation y, generation next, net generation, echo boomers, the 9/11 generation, and the Facebook generation) were born between 1977 and 1998, or from 1978 and 2000.

Catherine Colbert, a writer for Bizmology, says, “Millennials in general were born between 1980 and 2005,” but then her next words hit the bull’s-eye: “The age of this group isn’t as important as its attitude.”1

God bless Colbert. She seems to have realized that anyone who sees the world through the eyes of a millennial and makes judgments and evaluations according to the values of a millennial should rightfully be called a millennial.

iStockphoto / andipantz

It’s not about age; it’s about attitude. It’s not about when you were born; it’s about how you see the world.

In this book, the word generation will be defined as, “life cohorts bonded by a set of values that dictate the prevailing worldview of the majority.”

Life cohorts, not birth cohorts. Everyone alive—regardless of their age—who sees the world through the lens of a particular set of values is part of that generation.

Very few people see the world today as they saw it in 1971. Most of the group that was born between 1946 and 1964—typically called baby boomers—have adopted the worldview typically ascribed to millennials. This means the boomers have lost their boomerness. A message that would have resonated in their hearts in 1971 will sound corny, contrived, and syrupy today:

ME |

I’d like to buy the world a home and furnish it with love, grow apple trees and honeybees and snow-white turtledoves. I’d like to teach the world to sing in perfect harmony. I’d like to buy the world a Coke and keep it company. It’s the real thing: Coca-Cola. What the world wants today: Coca Cola. |

When Coke’s famous Hilltop ad appeared on television in 1971, our throats got tight and our eyes got big as we whispered, “It’s just so meaningful.” But if that original Hilltop ad were played for the first time today, those same boomers would say, “Seriously? Apple trees? Honeybees? Snow-white turtledoves? You’re kidding, right? And exactly what has Coca-Cola ever done to facilitate world peace?”

The birth cohorts once called baby boomers see today’s world through a different lens than they used forty years ago. They’re no longer filtering their perceptions through the same set of values they used in 1972.

People change. We don’t remain who we were. This is why advertisers should target not an age group, but a belief system, a worldview, an attitude. (We’ll talk more about this and other uses of the Pendulum in Chapter 14.)

PhotoDune / CandyBoxImages

New values are introduced every forty years at a tipping point, also known as a fulcrum. This tipping point/fulcrum is where the Pendulum hangs directly downward, having just completed a Downswing and ready to begin the Upswing on the other side.

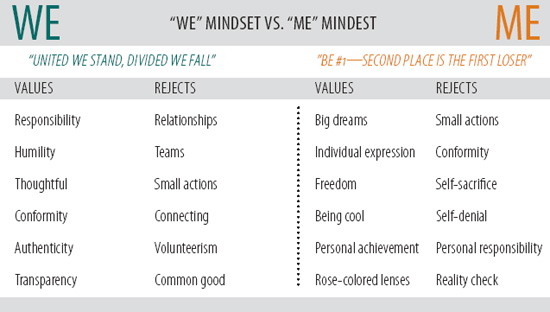

On one side of society’s Pendulum is “Me,” marked by the idealization of individuality and freedom of expression. The values of “Me” are the values of the grasshopper, not the ant. The grasshopper is happy-go-lucky, living always in the moment.

On the other side of the Pendulum is “We,” marked by the idealization of authenticity and belonging to a tribe, working together for the common good. The ants are “We,” trying to do the right thing, fulfilling their obligations, cleaning up the mess the grasshopper left behind.

A student of psychology may detect in the “Me” and the “We” an echo of Carl Jung’s and Edward Edinger’s theories regarding the ego and the self. Edinger described this ego/self duality as follows: “The ego is the seat of the subjective identity while the self is the seat of the objective identity.”2 The ego is the “Me,” the self, the “We.” Dr. Richard D. (Nick) Grant adds, “This creative tension between the ‘Me’ and the ‘We’ is the engine of qualitative development throughout life. The answer is neither one nor the other, it’s a both/and.”

Essentially, the ego is that bundle of wants and needs that looks out at the world from behind a pair of eyeballs. But our relationships with others determine the self. For instance, the ego (Me) may love chocolate, swimming, crossword puzzles, and being noticed and desired by the opposite sex. But the self (We) of that same woman is determined by her relationship to her children, she is their mother; her husband, she is his partner and wife; her friends, she is their loyal confidante; and her job, she is the manager of a team of agents in a real estate office.

iStockphoto / Camilo Torres

Were this woman to ask herself, “Who am I?” she could answer with any or all of the attributes listed above and be correct. But sometimes these attributes come into conflict, do they not?

The ego, “Me,” has personal needs, wants, and cravings, whereas the self, “We,” is defined by its relationships and connections.

Think of the ego as a vertical line measuring up and down: “Am I happy?” “Do I have status?” “What do you think of me now that I’ve said this thing, done this thing, bought this thing?”

The self, “We,” is a horizontal line that intersects the vertical. This horizontal line measures near and far. “Am I making a difference?” “Do I matter?” “How close are we now that I’ve said this thing, done this thing, given this thing away?”

Figure 3.1 Comparison of the mindset in a “WE” cycle versus that of a “ME” cycle.

This ego-self axis is perhaps most easily understood as the healthy tension that exists between desires and responsibilities. And as Dr. Nick Grant said, “The answer is neither one nor the other, it’s a both/and.”

According to Edinger, the psychological wellness of an individual (and we believe, by extension, a society) “depends on a living connection with the self (We) via a strong ego-self axis.”3 Sara Emily Perna adds, “Damage to the axis severs the connection between the conscious and unconscious realm, and an array of responses may spring forward from the alienation of the ego [Me] from the self [We]. Violence, hubris, ego inflation, guilt complexes, and self-abuse are common reactions to a split. The first half of life is thusly dedicated to the development of a healthy ego-self axis, the unraveling of the ego from the grasp of the self.”

In other words, it’s about finding balance. Responsibility, carried too far, becomes slavery. This is the danger of too much “We.” Conversely, freedom, carried too far, becomes depravity. This is the danger of too much “Me.”

The forces that pull a society two different ways are the ego and the self, the “Me” and the “We. “And we seem to travel between these two attractors as a group. Both are always present, of course. Even at the Zenith of the Pendulum’s arc, the opposing force is there. The position of the Pendulum is merely an indicator of which is currently more fashionable.

iStockphoto / alexsl

However, shifting the perspective of a society doesn’t happen with the flip of a switch. There is no single year in which the majority in a society decides to make the jump together. Instead, it’s rather like sitting on a riverbank watching canoes float by.

In the lead canoe are those pioneering “Alpha Voices” in literature and technology, the most forward thinkers in a society, fully ten years ahead of the crowd. In the second canoe, five years later, are innovators in music, providing an attitude and a voice to the coming new perspective that the forward thinkers in literature and technology had advanced. Then, five years after that, this new music becomes mainstream, as more and more people begin to embrace the new perspective. This is the “tipping point,” when the water begins to move swiftly and the scenery begins changing rapidly. These rapids in the river last six years. At the end of this six-year transitionary window, the pace of change slows dramatically as we begin to take a good thing too far.

Due to the fact that there is no single year when the majority of a society makes the jump to new values together, you’ll notice the final year of one perspective is also the beginning year of another. We speak of 1923–1943 as being the Upswing of the “We,” and 1943–1963 as the Downswing of the “We.” So is 1943 Upswing or Downswing?

It’s both. Early adopters of a new perspective begin losing their zeal for the old perspective a little sooner than the majority and late adopters will be found clinging to the old values as much as six years later. Not all the canoes reach the rapids simultaneously.

If a person chooses to get mathematically legalistic about all this and takes the position that a year “must either be one or the other. It can’t be part of an Upswing and a Downswing at the same time,” then that person will quickly come to the conclusion that each forty-year window of transformation is actually thirty-nine years, not forty. Or they will look at our lists of “We” Zeniths and “Me” Zeniths that happen only once every eighty years and say, “Well, by that same logic, if two windows technically come to seventy-nine years, then a single window must be thirty-nine and a half years.”

Okay, you can think of it that way if you want.

But you’ll be wrong.