Isaac Asimov’s famous science fiction series Foundation is built on the idea that masses of people are predictable, whereas individuals are not. The protagonist of that series, a mathematician named Hari Seldon, spent his life developing “psychohistory,” a branch of sociology analogous to mathematical physics. Leveraging the laws of mass action, psychohistory can predict the future, but only on a large scale; it is unreliable on a small scale.1

Like all good science fiction, Foundation is built on a central idea that is perfectly plausible.

The ancient Chinese named the recurrent dualities of the universe “yin” and “yang.” Modern politicos call them liberalism and conservatism. Electricians call their dualities positive and negative. Investors call their dualities risk and reward. In the movie Unbreakable, Samuel L. Jackson speaks of duality theatrically: “Now that we know who you are, I know who I am.”

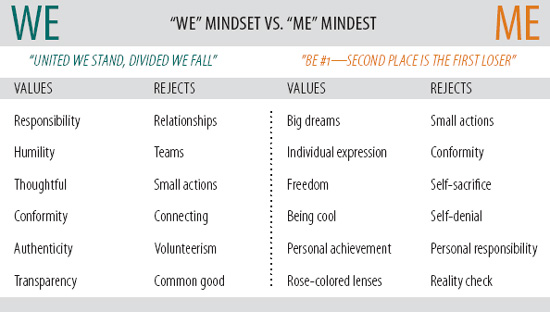

Figure 4.1 Comparison of the mindset in a “WE” cycle versus that of a “ME” cycle.

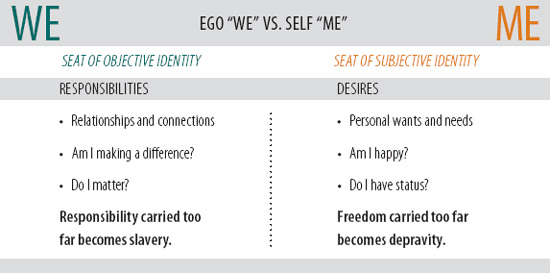

Figure 4.2 Comparison of Ego vs. Self.

But it was Isaac Newton who spoke of duality most famously: “For every action there is an equal, but opposite, reaction.”

When faced with the concept of duality, small minds will often cling to one and disparage the other. You know people like this, don’t you? You hear them say things like, “It has to be either one way or the other—it can’t be both.”

When Albert Einstein was serving as the proctor for a university test on advanced theoretical physics, a student raised his hand and said, “Sir, I think there’s been a mistake. This is the same test we were given last year.” And Albert replied, “Yes, the test is the same as last year, but this year the answers are different.”

Albert could just as easily have been talking about society’s Pendulum: “This year the answers are different.”

Ferdinand Schmutzer

The opposite of a correct statement is a false statement. But the opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth.

As improbable as it sounds, quantum mechanics tells us that matter can be in two places at once. So with your permission, we’re going to maintain that the Zenith year of each forty-year cycle can likewise be the final year of an Upswing and the first year of a Downswing simultaneously.

Figure 4.3 Examples of duality.

| THE CONCEPT OF DUALITY | |

| “The opposite of a correct statement is a false statement. But the opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth.”—Niels Bohr | |

• Yin • Positive • Good • Risk • Liberalism • Action |

• Yang • Negative • Evil • Reward • Conservatism • Reaction |