The clouds are gathering, they are gathering in a place, the clouds and the people, and the place waits calmly and in anticipation. The cloud turns, pointing like a spear towards our homeland of Rorruwuy.

When we used to go to Rorruwuy and Mum was there sitting under the tree, she’d see us coming and she’d start doing the milkarri of this songspiral, because we were gathering back at the homeland. She would greet us with milkarri, sing about the clouds, because we were returning home. That’s why, when we sing about sharks to people who are sick, they are not afraid. They are returning to their homeland, to their backbone, their foundation, their lirrwi, the layers of charcoal buried in the sand. They are returning to the essence of the land.

Rinydjalŋu is our homeland’s deep and sacred source. It is a place we protect as the source of our life. Each clan has their own area like this within their homeland. It’s an asset for them. It’s our children’s property, our property. Our Rinydjalŋu is like a bathi, a basket, it holds everything. The Dätiwuy and Ŋaymil children have the authority for the Rinydjalŋu. They have the responsibility and authority because Dätiwuy or Ŋaymil gave birth to them. Dätiwuy or Ŋaymil land gave birth to them as well. If they have to make a decision about that Rinydjalŋu, it has to be a consensus. If one or more disagrees then the thing doesn’t happen. The children have the right to guide the Rinydjalŋu.

The rule says children of Dätiwuy and Ŋaymil have to protect their Rinydjalŋu as the source of their life, their mother land. They have to speak for Rinydjalŋu. A Rinydjalŋu shelter can be built for someone if they are sick or need protection. The shelter becomes the source of protection. The children will stand and talk and protect it; protecting, defending their mother.

We are Dätiwuy from Rorruwuy and we are the land.

Gathering is larrpan, the long cloud, on display up high in the sky. The larrpan is the spear of Djambuwal, Thunderman, and it points towards my homeland, my Rinydjalŋu, my wäŋa, my home of the shark.

When the men and boys dance this songspiral, they hold their spears over their heads, looking like the long cloud larrpan, signalling the cloud with their hands and arms; slowly they turn it around, pointing to a body of water, to the stingray. It is the Thunderman who can control the weather; he can turn and move the cloud to point to each clan. The Thunderman is pointing the cloud, the spear, pointing it to the water. The action of turning to point is bilyunmaraŋalnha. That’s the reason the dancers point their spears to their knees, pointing towards the stingray in the body of water.

And this land, this Rinydjalŋu, this homeland, is still. It is a quiet, calm time of day in this home of the shark, in Rorruwuy. There is a feeling of anticipation with the clouds up high in the sky.

The spear point of the cloud turns to the different areas of the land. Each place is named in turn, by its sacred names. Now it turns to point at the Bon, the muddy waters of Rorruwuy. Ritjililimirr is another name for that muddy water, the name of our second eldest sister.

The spear cloud points like a compass. In the buŋgul, when we sing, we call a direction, we call a clan and the dancers turn in that direction, where the homeland is, with a spear held above their head. We’d like to make an activity for schoolchildren based on this, make a chart like a clock, and when the schoolkids hear the songspiral, they’ll know where to turn. It will point to the homelands and we can call their names out.

The spear point of the cloud is turning towards ritjililimirr. The water evaporates, the clouds gather, there is a stillness there. Waiting for the Thunderman to summon the clouds together.

This cloud is up in the sky, displayed in the sky. It is suspended there for the Dätiwuy people who live at Rorruwuy, for Dätiwuy and Ŋaymil people, two Dhuwa clans. Dätiwuy’s deep name is Bulurruma. Ŋaymil’s is Dharrapaŋan. Mali-Wutjawuy is the spirit of the land and the past, present and future people from that Country. Mali is a reflection or a shadow. It is also what we call a copy. So Mali-Wutjawuy is a cloud and its shadow, its reflection and its spirit. It represents the people and the land that is in the shadow of the cloud, from that place. Mali-Wutjawuy, the people from that land, that Country, Wutjawuy.

Another clan name for both Ŋaymil and Dätiwuy is Dharrapaŋan Mel’mari—both of us together, these two Dhuwa groups. Mel is the eye, mari, shark is the danger. We are the eye of the shark. It represents our clans. When you look at the shark’s eye you see the power in it, the inner sense. The shark, it has the power, it protects its territory. It could be friendly but if you get close to the shark, wow, we don’t know what it will do.

We have inner strength, a sense of ‘Don’t mess with me’. We are straight talkers, confident to talk in public. When we talk, we don’t talk quickly, we explain. If you are stepping in our territory, you need to understand our point of view. There are borders. There are things that others can’t step into. Always there are borders and we need to respect the limits. If you threaten us, we will tell you straight.

We are also a gentle people, we are people who help each other, we work with people. Some people will tell you we are kind, beautiful people, but others will tell you we are aggressive. Believe them both. It depends on the circumstances, what is around us.

We are Mel’mari. So the child of our clan knows how to step into that water, how to step into the muddy water to find a stingray, we know that muddy water, that Bon. We know how to hunt there. The child knows, we know. Only we know. It is all muddy. It is all ritjililimirr, muddy water.

Sometimes when other Yolŋu see us they say ‘dholuwuy Yolŋu’, people of the muddy water. When the water runs from our grandmother’s Country, Dhälinbuy on the Cato River, to Rorruwuy, it becomes muddy. Everywhere are crabs, sharks, stingray. When we dance, we show the barb of the stingray and then we spear it. There are lots of bäru, crocodiles, so we have to know the Country to survive. Every time we go out hunting, we get a long stick and use it to feel for the stingray when we are walking.

When we dance the shark songspiral it’s very dangerous because it’s about how the shark owns the territory. There is spiritual danger. It’s very powerful. It can be calm but it can be angry, like us. There is a dangerous part of songspirals, a good part of songspirals, an emotional part of songspirals. All these together.

The spear turns around pointing to the other groups and lands, bilyunmaraŋalnha. When we dance, we do this; the singers sing a place and the dancers know which way to turn and point to that land. Slowly, carefully, we name and map Country and the clans. We bring it to life, we respect and honour it. The cloud points to and acknowledges the other areas, the people and clans who sing cloud songs: Gälpu, Ŋaymil, Rirratjiŋu, Djapu, Djamparrpuyŋu, Dätiwuy, Dhudi-djapu.

Bon waywayun yukurra, we are the domain of the shark. Larrpan, that cloud formation in the sky, it invokes us, connects us with the land, the water and the sky. It proclaims the domain of the shark. It is the people of Rorruwuy.

When we sing this song, when we do milkarri of this song, any song, it is spiritual and the emotions come up. All the emotions come up, depending on the situation. There might be sadness, happiness, anger, joy. Emotions are so important to songspirals.

We can’t be happy all the time. If something breaks, we must cry. If we are happy, we must laugh. It is the same with the land, with the wind and currents, the animals: they all have emotion. When milkarri comes, when us women cry, if something bad happens, we’ve got to cry, it’s part of us. It’s all about connecting us to the land.

We are not just crying with tears coming down, we are singing too. That is milkarri. We are healing.

After Cyclone Nathan came through Bawaka in 2015, Ritjilili was crying because the trees, the land, were hurt. That was a big cyclone that came right through here. It uprooted trees, lots of them had their tops or branches blown off, and lots of the buildings were damaged. Many homelands were badly impacted by the cyclones that year. People were sleeping in tents and some of the roads were blocked for months. The sand was gone from the beach at Bawaka, and we could see the roots of the coconuts, the tamarind and the casuarinas, all bare. Sometimes we cry in silence, between the emotion and the singing, inside the heart.

All these trees, uprooted and damaged. When our kids first arrived after the cyclone, they just came and touched them. They said, ‘Marrkapmi, my dear ones, it is alright.’ That’s why we take the children to the homelands, so they can see. Maybe they will have a tear or two.

We came back a month later. Our eldest sister, Laklak, had been sick. We all piled in the troopie to go out there. Sarah and her family were there too. It was a time when we were sharing this songspiral. We were working on it together, the Gathering of the Clouds, and we had gathered. We needed to be out there at Bawaka.

We saw the new leaves were coming, and knowing that everything was coming back again, that the sand was coming back, we felt happy. The first thing we did when we got out of the truck and we saw the sand coming back was feel happy. The land knows this, it communicates.

The young leaves were red and fresh. Country knows how to heal. Milkarri helps that. It is a wondrous thing. If none of us came here, some of those trees would be dead. That beautiful tamarind tree that we sit under, the one that gives us shade, a big piece of iron crashed into it, wounded it, but because it knows we are here, it is starting to grow back.

In our songspirals, we do milkarri with the land, the land does milkarri with us. We have a sense of belonging, longing for the land, missing the land. We are homesick for the land, for the past. We have sadness for the state of the land, happiness for the state of the land. Sometimes it is so emotional because you haven’t been to that Country for a long time. Maybe we never will get there. Yet we see it through the milkarri. We cry milkarri and we see people walking on the beach, sitting there looking out at the sea.

If we do milkarri without the names, without using the deep names, the emotions won’t come out in the same way. If we do milkarri with the deep names, we feel better, we have given something back. It is healing for us and the land. That is why Yolŋu cry milkarri, to let out emotions in public. Keeping emotions in makes us sick. If we get it out, we feel good. It shows respect to other clans, to other people. It shows that we share the emotion too. Everyone is connected in the Yolŋu world, through kinship, through language and through songspirals.

And everyone has a role: women cry milkarri, men sing with clapsticks and yidaki. Women add harmony, balance, power, and they deepen the emotion. When men hear milkarri it makes them proud of their relatives and it gives them power as well, it helps them have that emotion. When the women are doing milkarri, it helps the men cry. They’re pouring out their emotions, not hiding them. The women allow them to let their emotions out. These are the hidden tears for men. Milkarri allows the men to cry with the miyalk, the women. And when women are doing milkarri, it helps the men to be powerful.

Most ŋäpaki who write about songspirals are professors and they write about it in an academic way. It can be abstract and disconnected from life. Sometimes they don’t do it well. The emotion isn’t there. It’s important to talk about this because we need to get the depth.

Also, when some ŋäpaki come, they see our dances as decorative, like a disco or a performance only for tourists, but it is totally different. We don’t just go in and dance. It must be done by the right people, in the right way, at the right time. We have strict laws about this. And it must be done with emotion.

We all feel the emotion, as the clouds gather, as we do milkarri. The clouds point to our homelands that have nurtured us, our source of life, the givers of knowledge and philosophy. They bring us together.

That land in Yirrkala, right at the point where the cliff is, that is where Djambuwal the Thunderman lives. This cliff is Djawuluku, Dhawunyilnyil, Dhawulpaŋu, Ŋalarra. All this weather starts at Yirrkala. That power is coming from there, going to Rorruwuy, to our place, our homeland, the home of the shark. The spear cloud points, marking the land, naming the areas, bringing the clans together.

When the Thunderman points, he is labelling the areas, giving the scientific names of the clans, then he calls all the clouds to form and then the darkness comes. The rain, it isn’t normal rain, it is the end-of-days rain, really dark and heavy. Maybe it’s going to wash away the land, wash away the track. Whenever you are standing there watching the rain come towards you and you think, ‘What am I going to do, stand here or find shelter?’, that is the scene the Thunderman is creating, the clouds becoming the rain. Sometimes when we see the lightning in that direction we say, ‘Ahh, it’s raining at Rorruwuy.’

There are two types of rain, the heavy rain is Dhuwa and the light rain, just a sprinkle, is Yirritja. Thunderman has a plan: some tribes get the lighter rain, but at Rorruwuy Thunderman goes into the water and gives his feelings to the water, to the stingray and to the shark. When he jumps into the brackish water his feeling goes into the water. Other clans have rain, but Rorruwuy has the stingray as well as the rain. That’s why the Thunderman turns his spear down to the water. He is tapping the water with his spear to see if there is danger around.

When someone passes away, the rain is milkarri. Everything is about life itself. The land that we are on, the sun we see, we are related to one another. Sometimes we don’t see it, but if we look through ourselves and nature we will find it. The rain is very important for the land. It cools the land and gives energy to the plants to grow. Just imagine if there was no rain—what would happen to the trees, nature and all of us?

The clans and the clouds are one. As a writing collective we gather too. The songspirals have brought in Sarah, Kate and Sandie.

At sunrise, at Bawaka, we do milkarri for visitors, for tourists and guests. This is where Sarah, Kate and Sandie first learnt about milkarri, where they felt it, the emotion, the sounds, where they got further understandings of us, of our connection with Country and of the deep role women play through milkarri. We wanted to continue Mum’s idea of doing the milkarri at Garma and bring it to Bawaka, to share this with ŋäpaki, to greet the new day. We do milkarri for the day, to remember the day, create the day.

In the hushed darkness we sit. It is not yet dawn, there is no light yet. The stars are bright above as we go and take our seats. It is cool too. We might have a rug around our shoulders. There are chairs for the Elders to sit on, blankets and mats for others. We sit quietly, just the sound of gentle movement. The sound of a light breeze.

Then we begin. There is a beautiful high keening, a long note, and those that can, join as they are ready. Kate, Sandie and Sarah, and the younger women, they sit feeling the sound in them, around them, through them. They often have their eyes closed. Sometimes they cry. It moves them, changes them. We cry milkarri and they are part of it.

In the darkness before dawn, we do milkarri for the land, the mist, the breeze, the webs of the spiders. We do milkarri for those people who have passed away and been with us before, their spirits. We do milkarri for the peewee bird, bidiwidi, and djilawurr, the scrub hen.

The pre-dawn comes, the stars fade until the morning star stands brightly there alone. We do milkarri for the first bird that sings, waking the other animals up. The birds awake. We finish and the land is alive. We cry milkarri for the new day.

We have been gathering and writing this book together for five years now. It has been a long process to decide what we wanted to share, and to try to work out a good way to share it. We have learnt a lot ourselves and we have taught Kate, Sandie and Sarah a lot too. We used to joke that they were in their nappies. They are out of their nappies now. They know that our relationships bring responsibility, that they are part of gurrutu too.

We have met at our homeland Bawaka many times to work on the book. This is where we were when we decided to write it, when Laklak our eldest sister said it would be our next project. And we have been together in Yirrkala, the town where we younger sisters live. Twice we’ve gathered at Garma. We have been down south too, to Sydney, to Bellingen and Bangalow in northern New South Wales, to Adelaide, and to Christchurch in New Zealand. We have had many, many meetings and talks, much food gathered, cooked and shared, many baskets woven, walks taken, rides in cars and planes and 4WDs. Some of us have even travelled together to Canada. That is where we checked over some of the drafts of the book, if you can imagine.

Wherever we are, others seem to gather too—social media points friends and family far and near in the direction of the gathering, and gather we do.

We have shared with Sandie, Sarah and Kate about the meaning of the songspirals, we have called family to share with us the words and tune, to check we are doing the right thing. We have translated the words together—Banbapuy our youngest sister has done a lot of that. Together, we go through line by line, and also discuss the overall meaning. Sometimes, we will write pages and pages about a single word. There is so much depth to communicate.

In August 2016 we were at Garma talking about our work together. We found ourselves talking about märr, love, again and again. That was one word that got us talking. We ended up writing a whole article all about it. Märr, love, and the raki, string, bind us. This is milkarri too, the love of watching Dawu and Ruwu, Sarah’s and Kate’s little girls, twirling and whirling in the buŋgul with Mayutu, Merrkiyawuy’s daughter; the love of camping with the Art Centre gang in a big family group, sitting around the campfire at night and running off to celebrate the plethora of brilliant Yolŋu bands on show; the love of sitting on the sand of the open-air Gapan Gallery, sitting under the white ghost trees, the light reflecting off the clean soft white sand, sitting and drawing sand pictures of our relationships; the connections, the love between us and how it binds. And our love is not an individual thing. It is about connection, the way our gurrutu and our djalkiri, our foundations, overlap, how we work together and how we all overlap with the land.

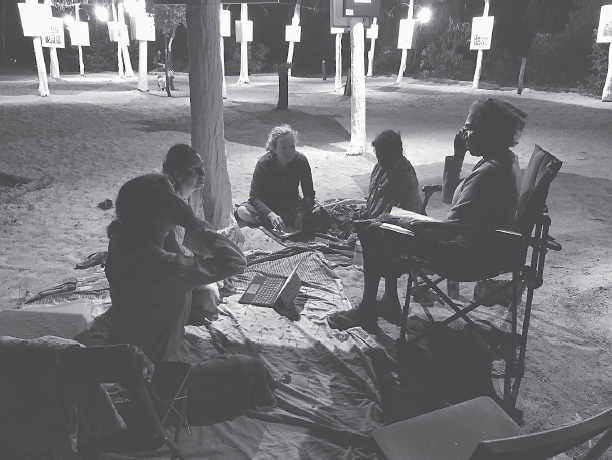

Working on the book at the Gapan Gallery, Garma Festival 2016. (Authors’ collection)

And in the middle is love. The connections make us whole, but we must have love in the middle. It is not a selfish love, but a sharing love. It is not a static love but one that is always emerging. It is a love for each other, for our families, for our knowledge, for sharing. It is a love for how we always bounce off each other and share our knowledges in different ways.

Love emerged and emerges, wherever we are, whatever we do. It spirals out and round, in our connections with each other and the land. As with milkarri.