Belonging and longing to be with Country

Wititj, the Rainbow Serpent, claims the territory through singing. The land is sacred. There are many different territories, with many different tribes and clan lands. Wititj didn’t claim it for the crown with a flag like the English. She sang that Country, made it with her body. The snake casts out by singing, claims the territory as sacred, makes that area. She sings Country.

When Laklak became tired, became sick, our daughter Djawundil, Laklak’s eldest, went with her to Adelaide for a big operation. The surgeon in Darwin had met with Laklak and Djawundil and shown them a picture of a tumour in Laklak’s brain the size of an orange.

The surgeon started speaking with Djawundil in English. Djawundil interrupted him and said, ‘You can speak in English to Mum, she is a teacher, she can understand everything.’

The surgeon told Laklak and Djawundil that Laklak needed an operation in Adelaide to remove the tumour and release the pressure in her brain. Back in Yirrkala the family had a meeting and we all agreed Laklak needed to go to Adelaide for her operation and we didn’t want anyone to go with her but Djawundil.

Laklak and Djawundil had to go far from home for this operation. Like many other Yolŋu they had to go down to Adelaide, far away from family, away from home. They didn’t want to go to Adelaide. The last time they were there was with Laklak’s husband, Batjaŋ, when he was sick. Going to Adelaide is associated with being sick and being away from home. Laklak didn’t want to go as she was afraid she wouldn’t come back. It was a big responsibility for our daughter Djawundil to be the one to go with her.

The operation was successful in removing the tumour but after the operation the neurosurgeon came to tell Djawundil that something went wrong, Laklak’s brain kept bleeding, and she had a stroke. They moved Laklak into the intensive care unit and they didn’t know if she would live. She went in for another operation to stop the bleeding and Djawundil called Kate, who flew to Adelaide to be with her. They sat in that waiting room a long, long time. The surgeon told them he had managed to stop the bleeding but that he didn’t know how this would affect Laklak. He didn’t know if she would live. For many, many weeks Laklak was in hospital. She regained consciousness and she slowly started eating but she had lost some of her language, some of her memory. She lost her ability to speak English. She would only talk Yolŋu matha and Djawundil had to translate to the nurses and hospital staff.

Although she lost some of her memory she could use her hands, they were always busy, always trying to pull out the tubes that were helping her to breathe and take off the helmet that was protecting her head as it healed from the operation. To keep her hands busy, Djawundil and Kate would give her nuts from the gum trees outside the hospital and she would try to peel them. It was important for her to go home, she wanted to go home, to be healed by Country, listening to language and being with family. The sense of belonging is important, it is a feeling, a connection with Country, with home.

Being with Country is of fundamental importance to Yolŋu. In the Yolŋu world, wherever we are in Arnhem Land, wherever we are, we are connected in some way to people, to plants. It is about always being in relationship, intertwined and connected. The Law is ancient. Old, old, old. If we dig down, we will find ashes, charcoal, lirrwi, from a long time ago. That is what songspirals are all about.

Sometimes, when people are sick and away from home, they sing, or listen to music from home, maybe East Journey, Gurrumul, maybe Yothu Yindi. It’s like taking them back to their Country, seeing everything in song because they can’t be there. The songs have their own language. Just imagine if we lose our language, there wouldn’t be songspirals. Then the land would be silent, it wouldn’t be alive.

We all start out speaking Dhuwaya as our Yolŋu matha. It’s our common language between the clans, a baby language, spoken by children. That’s all a lot of Yolŋu can speak, they can’t speak their own clan language. So, those clan languages need us. Us sisters were all Dhuwaya speakers. That’s why we started studying our clan language and why it was important. When we were younger, we went to Rorruwuy and stayed there for two weeks working with our father. Banbapuy was still too little to come with us. We came back speaking our own clan language. Banbapuy heard us. When Mum heard us, she didn’t laugh at us, she talked back at us in that language. It is all there, it just needs to come out of the mouth. As we say, the tongue turns.

Doing milkarri would get the language coming back. When we sing the clan song, the words have to be in that clan language. That is the Law. This book is a drop in a pond, we hope it sets lots of ripples going out.

When we sing, everything exists. That’s why when the two Djan’kawu Sisters, who created the land, when they came with the Wapitja, they penetrated the ground with the stick and they chanted, and everything came alive. And, of course, giving birth to the land they had to put systems in place to follow, to keep it going, to make it a better place. They put language as well. When we speak we are speaking from the land, from the common ground. So if you know where you belong, you are able to speak.

Language is power. It identifies the person, who you are. When a person is gone, they are guided by that songspiral, where they come from. Even if you live down south, you are guided by that song, where you belong both in life and death. The songspiral takes you back to the land, to Country.

Even though our eldest sister and our daughter were far from home, Yolŋu and ŋäpaki family and friends based in or visiting Adelaide rallied around and helped them. Some of our family who were down from the homeland of Mäpuru looking after other loved ones, spent time with Djawundil in the hospital. Martin Deadman, who had been adopted by a family from Dhälinbuy, and his partner, neurologist Cindy Molloy, looked after Djawundil. They took her into their home for the weekends, helped her to understand the hospital system and spoke to the right people to get them to agree to let Laklak recover back home. They helped to organise a charter CareFlight to take Laklak back to Yirrkala so she could be around her family. The CareFlight jet arrived and they put the crash helmet on Laklak’s head to keep her safe, to protect her head and to protect that knowledge.

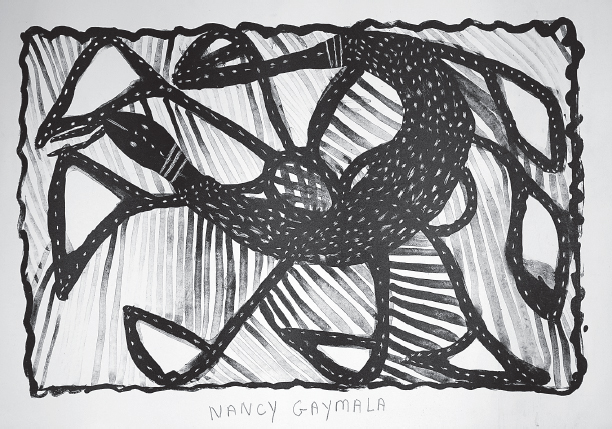

Gaymala Yunupiŋu, Djaykuŋ (1992). (The Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Art Centre archives)

It will be a long recovery, but being back on Country gives Laklak strength. It is important she is around people who speak in her language, who sing to her; language is part of belonging, her connection. It’s like when we visited Bawaka after the cyclone in 2015, when all the trees at Bawaka were broken and bare. The tamarind tree would have died if none of us went to care for it. Down south, sometimes trees die as they have no one, no one to talk to them, to touch them.

It’s like that with Laklak; down in Adelaide she had only Djawundil. To recover, she needs to sit under the djomula, the casuarinas, to listen, be a part of Country. To touch the sand, to peel the gunga (pandanus leaves). You remember in the hospital she took the nuts and played with them in her hands? She needs to touch the land and be part of it to recover. Sitting on the sand, feeling the sand, the coolness, everything. It is the pedagogy of Yolŋu, of everything. It is a way of learning, another way of learning. It is a real-life learning, a learning journey of another sort.

It’s important that Laklak tries to sing again, to get her memory back. She can’t do that without being on the land. Even if a person knows how to sing, that person has to know the map of the Country. Because when they sing, do milkarri, they think about the land, where everything is. They know. They have to know. If they don’t know the area it is meaningless, it is just a song. The milkarri needs to be from the land. It is not only that we want to belong to the land, but the land longs for people too. It is giving and taking. What we give, we take, it gives, it takes.

We sisters sing with Laklak, we know the importance of her remembering her language. She has lost a bit of memory but she has it there. She was keening the other day. She keened and she cried. She started to sing, some words came back. Ritjilili started first, then Laklak heard and then they started doing milkarri together. Ritjilili learnt how to do milkarri from Laklak. Merrkiyawuy too. Another time Laklak was sitting in a chair outside Nalkuma’s house in Yirrkala and she heard manikay going on for a funeral. Banbapuy said, ‘Look, Laklak is crying.’ Laklak said she could hear her sister clan.

Laklak needs to be on her land to rest, to heal. She needs to be able to rest her weary head as Wititj does. And she is healing. She came back to Yirrkala and to Bawaka.

After some months we decided we needed to do a cleansing ceremony for her. We do this when someone has been very sick. We needed to cleanse her. It turned out that her cleansing ceremony became deeper, a way to honour her in both Yolŋu and ŋäpaki systems. We honoured her knowledge, stories, the way she keeps the songspirals alive.

It is through the songspirals that Wititj the snake claims her territory. Through song she becomes Country.