Direct Democracy and Constitutional Change in the US

Institutional Learning from State Laboratories

It is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.

Justice Brandeis (dissenting opinion), New State Ice Co v Liebmann2

Traditionally, research of constitutional law scholars in the US mainly focuses on the federal Constitution, thereby often neglecting the rich source of constitutional tradition on the state level. Nevertheless, states may serve as laboratories, yielding useful insights in the successes and failures of their experiments. It is the aim of this essay to fill a gap in the literature by thoroughly analysing the constitutional amendment procedures in all 50 state constitutions.

Article V of the federal Constitution maps out four different paths to amendment.3 Regarding the initiative to propose amendments, a two-thirds vote in the House and the Senate is required, or two-thirds of the state legislatures can call a national proposing convention. Thereafter, Congress has the power to choose the mode of ratification: approval by three-fourths of the state legislatures, or by conventions in three-fourths of the states. As a result, the 13 least populous states—together merely representing approximately 4.4 per cent of the total US population4—could in theory veto any amendment in the ratification stage. The equal representation of states in the Senate also gives small states a disproportional amount of power in the proposing phase of the amendment process, while Article V requires unanimity to alter the equal suffrage clause.

The four paths to constitutional change in Article V only involve legislatures. The federal constitutional amendment procedure does not provide any form of direct democracy, such as an initiative petition by citizens or a popular referendum, and has not been altered since its adoption 228 years ago. Article V champions federalism via involvement of federal and state legislatures over direct involvement of the People. At least one could argue that the People are more directly involved at the state level than at the federal level. In 1787 when the Constitution was enacted, the People identified more with their state level rather than with their nation. Nevertheless, it remains an open question whether Article V should be read as the exclusive way to alter the federal Constitution. Based on the principle of popular sovereignty one could argue that the People have an inalienable right to alter or abolish the Constitution that they, themselves, have ordained and established.5

In contrast to Article V of the federal Constitution, the amendment procedures in the state constitutions have undergone numerous alterations and improvements. State tradition regarding amendment and revision procedures has in principle become more flexible than the onerous federal approach and is mainly characterised by direct democracy and majoritarian voting rules. The analysis of the 50 state constitutional amendment processes could serve as a starting point for a better informed normative debate about altering the amendment procedures in the states and on the federal level. If one reflects on the possible implementation of state experiments on the federal level in the future, one has to take into account the different features of the federal context, such as a higher likelihood of factionalism.

II.ARTICLE V OF THE US CONSTITUTION

A.The Four Classic Paths to Amendment

The first part of Article V of the Constitution provides the following paths for formal amendment of the Constitution: ‘The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose Amendments to this Constitution, or, on the Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the several states, shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments, which, in either Case, shall be valid to all Intents and Purposes, as part of this Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other Mode of Ratification may be proposed by the Congress.’

In other words, the amendment procedure can be initiated through the federal or state legislative level. Either a two-thirds vote of both Houses of Congress is necessary to propose an amendment or two-thirds of the state legislatures can oblige Congress to call a special convention to propose amendments. Hitherto, not a single constitutional amendment has been adopted via the latter option.6 Thereafter, the proposed amendment needs to be ratified by three-quarters of the states for approval. Congress may decide whether the states can act through their legislatures or via special ratifying conventions. There are no time limits to this procedure, although it would make sense to impose them.7

In an important empirical study, Donald Lutz analysed the constitutions of 32 countries as well as the 50 US states, which led to the remarkable conclusion that ‘the [federal] US Constitution is unusually, and probably excessively difficult to amend. The United States should move either to the strategy of using a referendum, in which case its amendment rate may well triple, or else reduce the number of states required for amendment ratification to two-thirds (from three-fourths) …’.8 Indeed, Article V does not provide any form of direct democracy, such as initiative petitions or referenda. It is still reminiscent of the initial fear of Southern slavocratic leaders for a popular vote.9

Moreover, the equal representation of states in the Senate gives small states substantially more power in the proposal stage of amendments than states with a large population. In addition, due to the required three-fourths supermajority of the states to approve any amendment, simple majorities of the delegates at state conventions or members of the state legislatures in the 13 least populous states, approximately only representing 2.22 per cent of the US population,10 could potentially block any amendment in the ratification stage. Moreover, calling a national proposing convention does not seem to be a preferred or feasible option for the states, so that a two-thirds vote of both chambers of Congress is usually necessary. Consequently, Congress has de facto always a veto power, which makes it unlikely to pass any amendment limiting the power of Congress or increasing the power of the state level.11

In conclusion, the current amendment process of Article V champions federalism over direct involvement of the People. Nevertheless, one could invoke the principle of popular sovereignty to defend a non-exclusive reading of Article V. Hereafter, the debate about an exclusive versus a non-exclusive reading of Article V will briefly be analysed.

B.Exclusive Reading of Article V

A majority of legal scholars support an exclusive reading of the amendment procedure in Article V of the federal Constitution in order to formally amend the Constitution.12 According to this view, one can only rely on this formal procedure to alter the Constitution. Moreover, it is widely acknowledged that in order to alter the amendment process of Article V itself one must first comply with the current amendment procedure in Article V.

Nevertheless, based on the principle of popular sovereignty one could argue that the People have an inalienable right to alter or abolish13 the Constitution that they, themselves, have ordained and established.14 This argument could be invoked to oppose a strict exclusive reading of the amendment procedure in Article V.

C.Non-Exclusive Reading of Article V

Contrary to the current mainstream reading of Article V as the exclusive way to formally amend the Constitution, one could argue that Article V supplements the inalienable right of the People to alter the rules governing them. Admittedly, based on an intra-textual argument, one could try to counter this argument by invoking that exclusivity is also implied in other provisions of the Constitution without being explicitly stipulated. For instance, the Article III roster of cases and controversies limits the federal court’s jurisdiction to the nine listed lawsuits without mentioning ‘only’.15

Nonetheless, three important arguments can be invoked to reject an exclusive reading of Article V:

1.popular sovereignty was the bedrock principle for the establishment of the Constitution and could also be invoked in favour of direct involvement of the People to alter the Constitution;

2.the Framers intentionally amended state constitutions without respecting several state amendment procedures, which required a non-exclusive reading of those Article V counterparts;

3.there has always been a strong constitutional tradition in the states of organising constitutional conventions outside the state constitutional provisions analogous to Article V.16

At the time of drafting Article V of the new US Constitution, the first state Constitutions did not constitute useful examples for drafting a provision about the constitutional amendment procedure.17 The first state Constitutions of Virginia (1776), North Carolina (1776) and New York (1777) did not encompass any explicit amendment process, while Connecticut and Rhode Island still lived under the old Crown Charters which also did not comprise any amendment procedure. New Jersey’s Constitution of 1776 and South Carolina’s Constitution of 1778 principally granted the state legislature the power to amend the Constitution by ordinary law-making.18,19 Delaware required a five-sevenths vote of the state legislature and Maryland demanded a legislative vote in two consecutive sessions with an election in between.20 However, all these state constitutions were not established through an act of direct popular involvement and did not regulate how the People themselves could have a say in the amendment process. Georgia’s Constitution of 1777 provided citizens with the right to petition for calling a proposing convention, but remained silent about the next step.21

Hence, those ten state constitutions by no means constituted valuable examples for drafting an amendment process to alter the federal Constitution which was uniquely ordained by the People. Only the Constitutions of Pennsylvania (1776), Massachusetts (1780) and New Hampshire (1776) were established by more direct democracy.22 They provided that an amendment process might be initiated at a fixed date or at fixed time intervals by an institution other than the legislature. However, those three documents remained silent about amendment through other means or at other times.23

The lack of useful examples at the state level establishing a detailed amendment process, which provided involvement of the People, was one of the reasons why the Framers did not include direct democracy in Article V. Consequently, the federal Constitution does not address the following fundamental and intriguing questions. Could citizens take the initiative to call a proposing convention without petitioning of the States? Could citizens petition to propose a specific amendment? Could a proposed amendment be ratified by popular vote in a referendum? In this regard, James Wilson argued in 1787 that ‘[t]he people may change the Constitution whenever and however they please. This is a right of which no positive institution can ever deprive them’.24 Besides options that favour more direct democracy, one could also pose the following two questions. Should Congress on its own be capable of calling a proposing convention without petitioning by the states? And, should the state legislatures be allowed to petition a ballot measure proposing a specific amendment?

An analysis of the constitutional tradition on the state level reveals that many states have already amended their constitution or adopted new constitutions via procedures involving the People, which were not provided in the constitutional amendment process of their state constitution.

In 1787, state governments had initially sent their delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia to amend the Articles of Confederation. There was originally no intention to abolish those Articles entirely. Article XIII of the Articles of Confederation stated that any amendment required the consent of all 13 state legislatures. This unanimity requirement, however, turned out to be de facto unattainable.25 Rhode Island even refused to send delegates to the Constitutional Convention.26 As a result, the delegates started drafting a constitution that did not require ratification by all 13 state legislatures. Pursuant to Article VII of the Constitution, approval by conventions in at least nine states was sufficient for the Constitution to enter into effect for the ratifying states. In other words, the amendment procedure in the Articles of Confederation was simply set aside.27

By seeking ratification of the Constitution through conventions in at least nine states, the delegates to Philadelphia intentionally sidestepped the required unanimity in Article XIII of the Articles of Confederation. Moreover, though often overlooked, the Constitution—being the Supreme Law28—also altered existing state constitutions and sidestepped the amendment procedures of the seven state constitutions encompassing such a procedure.29 Although the Constitution of Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and New Hampshire at that time prescribed a scheduled amendment procedure at a fixed date (1795 in Massachusetts) or at fixed time intervals (every seven years in New Hampshire and Pennsylvania), the Philadelphia delegates did not wait for those scheduled times to seek ratification of the Constitution. Moreover, four other state constitutions granted the power for amending the state constitution to the state legislature and thus not to state conventions. In New Jersey and South Carolina, the Constitution could be altered by ordinary law-making, in Delaware by a two-thirds vote of the state legislature, and in Maryland by a legislative vote in two consecutive sessions with an election in between.30 Consequently, those conscious acts of the Framers obviously relied on a non-exclusive reading of several state amendment procedures, which are counterparts of Article V of the federal Constitution.31

Moreover, Pennsylvania has already organised five proposing conventions, although its state constitution does not explicitly provide the option of calling a constitutional convention. Similarly, Massachusetts’ Constitution does not mention the option of a constitutional convention, even though four conventions have already been held.32 Bruce Ackerman wrote that before the Civil War at 16 occasions state legislatures have not interpreted the silence in their state constitutions as a reason for exclusivity.33 Moreover, Roger Hoar listed 34 conventions that have been held before 1917 in states of which the constitutions did not prescribe the option to call a convention.34

Akhil Amar argues that Article V should be read as the exclusive way for the federal and state legislators to propose and ratify amendments without involvement of the People, thereby expressing the distrust of the People against ‘imperfect representatives’.35 According to Amar, however, this viewpoint implies that Article V does not constrain the inalienable right of the People itself to alter the Constitution via a national referendum.36 Even if one defends such a view, one should in my opinion first attempt to adopt an explicit amendment to Article V in order to add more direct democracy to the amendment process.

In the book Our Undemocratic Constitution, Sanford Levinson convincingly advocates that the Constitution should be revised. However, arguing that the mechanism of Article V is too onerous, he provocatively (and hypothetically) proposes to organise a national referendum on the question: ‘Shall Congress call a national convention empowered to consider the adequacy of the Constitution and, if thought necessary, to draft a new constitution that, upon completion, will be submitted to the electorate for its approval or disapproval by majority vote? …’.37 Undoubtedly, the organisation of a proposing and ratifying referendum would have to rely on a non-exclusive reading of Article V in order to have binding force.38

In We The People: Foundations, Bruce Ackerman puts forth his enlightening concept of ‘constitutional moments’. During constitutional moments, citizens deliberately produce higher law-making that better reflects the will of the People than the acts of majoritarian institutions during normal politics, which for instance happened during the constitutional conventions at the Founding.39 Ackerman also endorses a non-exclusive reading of Article V and acknowledges that successful constitutional transformations or amendments can take place outside the formal amendment process. He believes that this for example happened during the New Deal, when democrats publicly and self-consciously sought a new constitutional solution to expand federal regulatory power outside the traditional amendment process of Article V. This took place under the lead of President Roosevelt, relying on the appointment of new judges in the Supreme Court.40

Federalism enables a people to try experiments in legislation and administration which could not be safely tried in a large centralised country. A comparatively small commonwealth like an American state easily makes and unmakes its laws; mistakes are not serious, for they are soon corrected; other states profit by the experience of a law or a method which has worked well or ill in the state that has tried it.

Viscount Bryce, The American Commonwealth (1888)41

Friedrich von Hayek introduced the insight that competition is a learning process.42 Dividing a country in several jurisdictions with its own legislative powers enables them to learn from each other’s successes and failures. Wallace Oates called this ‘institutional learning’ or ‘laboratory federalism’.43 Decentralisation enables the simultaneous occurrence of multiple policy experiments, such as different amendment processes.44 Competition between legislators may lead to innovation, which could generate improved institutional systems and legal rules. Decentralised jurisdictions could learn from each other and the federal level could also beneficially learn from state experiments. Thus, it is useful—though often neglected—to analyse the amendment procedures in the state constitutions, which have undergone numerous improvements.45

Each state has its own constitution, constitutional tradition, and distinct constitutional amendment procedure.46 There have been almost 150 state constitutions, which have been amended approximately 12,000 times.47 It is widely acknowledged that the state approach concerning amendment and revision is more flexible that the onerous federal approach.48 This contribution will analyse the different paths to constitutional amendment in the Article V counterparts of the current 50 state constitutions. An analysis of all 50 state constitutional amendment processes may serve as a starting point for a better informed normative debate about the amendment procedures on the federal and state level. In the near future, it is advisable that comprehensive empirical research would be carried out with regard to the actual practice and efficacy of the existing constitutional amendment procedures.

Generally, one can distinguish four different paths to proposing a constitutional amendment or revision in the states:

(1)proposal of the state legislature;

(2)popular initiative;

(3)calling a constitutional convention; and

(4)establishing a constitutional commission.

The ratification of proposed amendments and revisions usually takes place through a referendum.

A.Amendment by Proposal of the State Legislature

Currently, 49 state constitutions allow the state legislature to propose constitutional amendments which are then brought before the voters. In Delaware, however, the state legislature on its own can amend the Constitution in two consecutive sessions without popular vote.49 Hereafter, it will be examined how this constitutional amendment process differs from state to state, whereby we will mainly focus on three aspects. The following questions will be answered:

1.whether a proposed amendment needs to be approved by the state legislature during one or two legislative sessions, and whether a simple majority or supermajority vote of the legislature is required;

2.whether a proposed amendment can be put on the ballot during a general and/or special election; and

3.whether the popular vote requires a simple majority or supermajority of the voters to ratify the amendment.

i.One or Two Legislative Sessions—Supermajority vs Simple Majority Vote

In 35 states, an affirmative vote of the legislature during only one session is sufficient to propose an amendment. Ten states50 out of those 35 require a simple majority vote of the state legislature. Among those ten states, a remark should be made about the situation in Oklahoma and New Mexico. Oklahoma’s constitution prescribes a simple majority vote, unless the legislature puts the amendment on a special ballot in which case a two-thirds vote is required.51 Moreover, in New Mexico an amendment proposed by the state legislature that would restrict the rights created by Section 1 or Section 3 of Article VII or Section 8 and Section 10 of Article XII requires a three-fourths vote of the state legislature in order to be put on the ballot.52 Nine out of those 35 states require a 60 per cent supermajority vote to bring a proposed amendment before the voters.53 Among those nine states, Nebraska’s constitution imposes a supermajority of 80 per cent in order to submit a proposed amendment to a special election.54 In 16 states,55 a two-thirds vote in the state legislature is required to propose an amendment.

Besides those 35 states, the constitutional amendment procedure in two other states should be mentioned. South Carolina’s constitution prescribes that an amendment requires a two-thirds vote in one legislative session in order to bring it before the voters. However, after the approval of the voters, it returns to the legislature for a second, simple majority vote that must take place ‘after the election and before another’.56 In Pennsylvania, an amendment can only be brought before the voters after one session in case of a major emergency declared by the legislature by a two-thirds vote. Otherwise, an amendment proposal needs to be approved in two consecutive legislative sessions by a simple majority vote.57

In twelve states (including the aforementioned states South-Carolina and Pennsylvania), the state constitution requires votes in two consecutive sessions of the state legislature to propose amendments.58 Eight states require a simple majority vote in both sessions before seeking popular ratification.59 Although Delaware’s constitution also requires consideration in two consecutive sessions, the proposed amendment does not have to be brought before the voters to seek ratification.60 The other three states require different voting thresholds in the first and second session. As above-mentioned, in South Carolina a two-thirds vote of the state legislature in the first session refers a proposed amendment to the ballot and, after the popular vote, a simple majority vote of the state legislature is required to enter the amendment into force. Article XI, Section 3 of Tennessee’s Constitution uniquely requires a supermajority of two-thirds in the second session, which is different from the simple majority required in the first session. In Vermont, a two-thirds majority in the Senate and a simple majority in the House of Representatives are required in the first session, while a majority in both Houses is sufficient in the second session.61

In four states, a proposed amendment requires a simple majority in two legislative sessions or a supermajority vote in one session. The state legislature of Connecticut can choose to approve the proposal of an amendment by a supermajority vote of three-fourths in one session or a simple majority in two consecutive sessions.62 In Hawaii, the state legislature can approve a proposed amendment by a two-thirds vote in one session or a simple majority in two successive sessions of the state legislature.63 In New Jersey, a supermajority vote of 60 per cent in one session or a simple majority in two consecutive sessions is required to propose an amendment.64 As aforementioned, a simple majority vote in two successive sessions of the state legislature can bring a proposed amendment before the voters in Pennsylvania, but if a ‘major emergency threatens or is about to threaten the Commonwealth’ a two-thirds vote in the legislature can refer a proposed amendment to the ballot in one session.65

Finally, Oregon’s constitution uniquely regulates how a proposal to wholly or partially revise the Constitution can be brought before the voters outside a constitutional convention, namely with a two-thirds vote of the state legislature instead of the simple majority vote that is required to propose specific constitutional amendments.66

ii.Special vs General Election

In 20 states, amendments proposed by the state legislature can only trigger a popular vote in a general election.67 In addition to those 20 states, in Tennessee the popular vote on proposed amendments must specifically take place during the general election in a year that one can elect the governor.68 The option between a special or general election is made possible by 25 state constitutions.69 Article XIV, Section 2 of West Virginia’s constitution imposes the following unique condition regarding proposed amendments at a special election: ‘Whenever one or more amendments are submitted at a special election, no other question, issue or matter shall be voted upon at such special election.’ Finally, the state constitutions of New Hampshire, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Vermont do not mention whether the state legislature can bring an amendment before the voters at a general and/or special election.

After an affirmative vote of the state legislature to propose an amendment, a simple majority vote of the citizenry is required in 40 states in order to approve the proposed amendment.70 In addition, a proposed amendment demands a simple majority vote by the citizens of Louisiana. However, if the amendment affects more than five parishes or five municipalities in Louisiana, it requires approval by a majority vote state-wide and a majority vote in the respective parishes or municipalities that it affects.71 Moreover, Article XIV, Section 1 of the Maryland Constitution provides that certain constitutional amendments may apply to only one county or to the City of Baltimore. In that case, the proposed amendment must be approved by a majority vote state-wide and in the respective county or in Baltimore. In general, a simple majority of citizens voting on the proposed amendment is required, but in Minnesota and Wyoming a majority of the voters in the election is needed for approval of the proposed amendment.

Three states require a double majority vote by the citizens to ratify proposed amendments. This generally means that besides a simple majority of the votes cast on a particular proposal, a certain percentage of all the voters in the election is also required. This is necessary even if not all the voters in the election cast a vote for the proposed amendment. Consequently, this makes amending more difficult as it is likely to happen that less people vote on the proposed amendment than those who vote on the candidates in the election. Article XVII, Sections 2 and 3 of Hawaii’s Constitution outlines that a proposed amendment is approved in two cases. Firstly, an approval is achieved by a majority vote on the specific question if this majority also represents at least 50 per cent of all the votes generally cast in the election. Secondly, an approval is obtained in a special election by a majority of all the votes on the question if this majority represents at least 30 per cent of all the registered voters in the state at the time of the election. In Nebraska, a proposed amendment requires a majority vote on the amendment, in addition to at least 35 per cent of those voting in the election for any office.72 Tennessee’s Constitution demands a majority of those voting on the proposed amendment in addition to a majority of all the citizens of the state voting for governor.73 Besides those three states, in Utah only a vote of at least a majority of the electors of the state, which are voting at the next general election after the proposal of the amendment, is required to approve a proposed amendment.74

In Illinois an amendment proposed by the state legislature requires a simple majority of those casting a ballot for any office in that election or a supermajority vote of 60 per cent of the people voting on the question.75 Since 2006, Article XI, Section 5 of Florida’s Constitution requires a supermajority vote of 60 per cent of the people voting on the question for approval of a proposed amendment. In addition, a proposal to introduce a new State tax or fee in Florida via amendment of the state constitution requires the approval by two-thirds of the voters.76 Article 100 of New Hampshire’s Constitution requires a positive vote by two-thirds of the voters voting on the amendment. Finally, as aforementioned the state legislature of Delaware can uniquely amend the Constitution on its own in two consecutive sessions without popular vote. In conclusion, only Florida, New Hampshire, and Delaware substantially depart from the state tradition of direct democracy and majoritarian voting rules.

B.Amendment by Popular Initiative

One could advocate that citizens should be given the initiative to propose amendments via petitioning.77 In 18 states, voters are not only allowed to approve proposed amendment, but can also themselves initiate a proposal to amend the Constitution.78 Those states allow citizens to propose amendments through petitions that must be signed by a certain percentage of voters, ranging from three to 15 per cent of designated voting groups that vary in each constitutional provision.79 Nine states also have requirements about the territorial distribution of those signatures.80 When the required amount of voters signed the petitions, the proposed amendment is brought before the voters for ratification.

In 13 out of the 18 states, a simple majority of the voters is sufficient to ratify the proposed amendment.81 In addition, three states require a certain percentage of votes cast in the election in addition to a simple majority voting yes on the particular amendment. Massachusetts requires a simple majority of the voters voting on the particular amendment in addition to at least 30 per cent of the total number of ballots in the state election.82 Mississippi demands a simple majority of the votes on the particular amendment and at least 40 per cent of the total votes cast at the election.83 Nebraska requires a simple majority of the votes cast on the particular amendment and not less than 35 per cent of the total vote cast at the election at which the proposed amendment was submitted.84 In Florida, a supermajority vote of 60 per cent is needed for approval.85 Finally, in Illinois a ratification of a proposed amendment can be achieved by 60 per cent of the people voting on the amendment or a majority of those voting in the election.86

Nevertheless, in several states the requirements for this form of direct democracy are so strict that it has only been successfully used on rare occasions. Especially in Illinois, Massachusetts and Mississippi the gate to successful popular initiative has traditionally been extremely difficult to open, inter alia due to the following burdensome conditions:

(1)In Illinois, popular initiative is limited to amendments regarding structural and procedural subjects contained in Article IV of Illinois’ Constitution. Moreover, a proposed amendment needs to be approved by 60 per cent of the people voting on the amendment or a majority of those voting in the election.87

(2)In Massachusetts, initiative petitions are explicitly prohibited for numerous constitutional provisions.88 Furthermore, a proposed amendment by initiative petition can itself be amended a priori, that is, before the popular vote, by a 75 per cent vote of the state legislature in joint session. Additionally, an affirmative vote of at least 25 per cent in a joint meeting of the state legislature in two sessions is required before it can be put on the ballot. The voters can approve the initiative amendment or the legislative substitute by at least 30 per cent of the total number of ballots in the state election in addition to a majority of the voters voting on the particular amendment.89

(3)In Mississippi, an initiative petition to amend the Constitution must be signed by at least 12 per cent of the votes cast for all candidates for Governor in the last gubernatorial election and this must be accomplished within twelve months.90 Moreover, it cannot relate inter alia to the Bill of Rights and there are tough conditions regarding territorial distribution of the signatures. The signatures of the qualified electors from any congressional district may not exceed one-fifth of the total number of signatures required to qualify an initiative petition for placement upon the ballot, otherwise the signatures in a district that are in excess of one-fifth of the total number of signatures shall not be considered. Additionally, the initiative must mention the amount and source of revenue that is required for its implementation. If the initiative requires a reduction of government revenue or a reallocation of funding from currently funded programs, the text of the initiative must identify which program funding must be reduced or eliminated for its implementation. Finally, an approval or amendment of a constitutional initiative requires a majority vote of each house of the Legislature before it can be put on the ballot. In order to approve the original initiative or the proposed amendment approved by the legislature, a simple majority of the votes on the particular amendment and at least 40 per cent of the total votes cast at the election are required for ratification.

Over time, requirements have also been made substantially more stringent in Florida, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, Oklahoma, and Oregon. For instance, in 2006 an amendment to Article XI, Section 5 of Florida’s Constitution raised the percentage of voters required to approve a proposed amendment on the ballot from a simple majority to a supermajority vote of 60 per cent. In 1994, the Supreme Court of Nebraska ruled in Duggan v Beermann91 that a part of Article III, para 4 of Nevada’s Constitution has been implicitly repealed by an amendment to Article III, para 2 in 1988. Section 4 provides that the required number of signatures to put an amendment on the ballot is 10 per cent of the people who voted for governor in the most recent gubernatorial election, while section 2 has replaced this by 10 per cent of the state’s registered voters. Voters in Nevada need to approve constitutional amendments by initiative in two separate elections in order to become part of the state constitution.92 In Oklahoma, 15 per cent of the legal voters that cast a vote at the last general election for the Office of Governor are required in order to propose constitutional amendments by petition.93 Article IV, para 1b of Oregon’s Constitution is the only provision in a state constitution (ie, not in legislation) explicitly stating that it is unlawful to pay or receive money or other thing of value based on the number of signatures obtained for an initiative.

A proposing constitutional convention at the state level is a gathering of elected delegates with the aim of proposing major revisions and amendments to the existing state constitution or drafting an entirely new constitution. In 40 states it is now explicitly regulated how such a constitutional convention can be called:

(1)Firstly, 14 states constitutions provide a ballot measure that is automatically put on the ballot asking the voters whether a convention should be convened. This respectively takes place every ten years in five states,94 16 years in Michigan95 and 20 years in eight states.96 In twelve out of those 14 states, a simple majority vote of the People is sufficient to approve the question and Oklahoma’s constitution does not specify which majority is required.97 In contrast, Illinois demands a supermajority vote of 60 per cent of those voting on the question or a majority of those who cast a ballot for any office in the election.98

(2)Secondly, 27 state legislatures can autonomously decide to place such a question on the ballot to seek ratification by the voters in addition to or instead of an automatic ballot question. There are inter alia divergences with regard to:

(a)the percentage of votes in the state legislature required to put the question on the ballot: a simple majority vote in ten states,99 a 60 per cent vote in two states,100 and a two-thirds vote in fifteen states;101

(b)the number of legislative sessions in which the members of the legislature must vote in favour of the measure in order to put it on the ballot: one session in 26 states102 and two sessions in Kentucky;

(c)the percentage of citizens required to vote on the ballot in order to approve the question asking whether to organize a proposing convention: a simple majority in 26 states,103 and in Illinois a 60 per cent supermajority of those voting on the question or a majority of those who cast a ballot for any office in the election.104

In addition to an automatic ballot question, Alaska’s Constitution also provides the option for the state legislature to call a constitutional convention, though without further specifying the required percentage of the legislature’s vote, the number of legislative sessions or the percentage of voting citizens required to approve the question.105

(3)Thirdly, in six states the legislature can call a convention by a supermajority vote without the need of approval of the voters in order to convene the convention.106Additionally, four states107 allow citizens to take the initiative to petition for putting a question on the ballot whether the People want to call a constitutional convention. In those cases, a simple majority vote of the voting citizens is sufficient to approve the call for a convention.108

Besides those 40 states, Article XVIII Section 1 of Oregon’s Constitution states that ‘[n]o convention shall be called to amend or propose amendments to this Constitution, or to propose a new Constitution, unless the law providing for such convention shall first be approved by the people on a referendum vote at a regular general election’. Moreover, Article XXI of Arizona’s Constitution provides that the state legislature cannot call a convention ‘unless laws providing for such Convention shall first be approved by the people on a Referendum vote at a regular or special election …’

This analysis reveals that several states allow multiple methods to propose a call for a convention. In seven states a constitutional convention can be called both through an automatic ballot referral and via action of the state legislature seeking ratification of the voters by putting a question on the ballot.109 In addition to those two options, Montana’s constitution also allows popular initiative to put a question whether to call a convention on the ballot. In Connecticut, an automatic ballot question and a supermajority vote of the state legislature without approval of the voters are the two available paths to call a convention. South Dakota’s Constitution provides the latter option in addition to popular initiative. Besides these states, 32 states only allow one of those options.

In addition to the 42 states analysed above, Pennsylvania already organised five conventions, although its state constitution has never stipulated the rules how to call a constitutional convention. The last convention was held in 1968 during which the current constitution was adopted. Consequently, it seems to be considered as a legal tradition in Pennsylvania that the state legislature can vote to put a call for a constitutional convention on the ballot. Similarly, Massachusetts’ Constitution does not mention the option of a constitutional convention, but four conventions have already been held, the most recent one in 1917–1919. Finally, Vermont’s Constitution does not provide for constitutional conventions, although in 1969 the state legislature voted to put an advisory question to the ballot whether to organise a convention. Nevertheless, a majority of the voters answered the question negatively.110 Arkansas, Indiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, and Texas also do not have a constitutional provision about calling a constitutional convention.

Voters principally choose the delegates to the convention. As those delegates are only chosen for the purpose of the convention, a convention is considered to result in more direct democracy than a vote of the state legislature whose members are chosen for a bulk of tasks. The state constitution or the legislator usually prescribe the way in which the convention itself is organised. Afterwards, the proposal of major revisions or the draft of a new constitution by a convention is in principle brought before the voters for ratification, even if it is not explicitly prescribed by the state constitution. Out of the 40 states in which the Constitution explicitly provides how a constitutional convention can be called, 24 states111 explicitly require a simple majority vote of the people for ratification, two states112 require a 60 per cent vote, and New Hampshire requires a two-thirds vote. In the other 13 states,113 the state constitution does not explicitly mention which majority of the voters needs to vote yes in order to ratify the revisions proposed by a proposing constitutional convention.

Constitutional commissions are in principle established by the (state) legislature for the purpose of recommending constitutional amendments. Such a commission is generally not authorised to put its proposals directly on the ballot. For instance, since amendment 4 (1996), Article XI, para 1 of New Mexico’s Constitution authorises the establishment of an independent commission that can propose amendments to the state legislature for its review.

Florida is the only state in which the Constitution uniquely establishes two constitutional commissions that can directly bring proposed constitutional amendments before the voters without approval of the state legislature.114 The voters can approve those proposed measures with a 60 per cent majority.115 Firstly, the Constitution Revision Commission convenes every 20 years.116 Such a Constitution Revision Commission convened for the first time in 1977. In 2017, such a commission will convene for the third time. Secondly, also once every 20 years, the Florida Taxation and Budget Reform Commission convenes with the authority to directly propose constitutional amendments to the voters regarding taxation and the state budgetary process if two-thirds of the full commission, that is, 18 out of the 25 members, approve it.117 This commission convened for the first time in 2007. In 2008, only one recommendation of the 2007–08 Taxation and Budget Reform Commission made it to the ballot and it was rejected by the voters.

IV.ALTERATIONS TO THE FEDERAL AMENDMENT PROCEDURE

In light of the tradition of state constitutionalism as analysed in the previous chapter, reform proposals will be developed with regard to the federal amendment procedure. First, the proposals will focus on the possibility of introducing initiative petitions and constitutional referenda. Secondly, it will be illustrated that a popular vote is almost inseparably linked with a simple majority voting rule. It is the main aim of this section to revive the important debate about changing Article V of the US Constitution.118

Currently, two-thirds of both chambers of Congress can directly propose amendments to the federal Constitution. One could advocate that citizens should also be given the initiative to propose amendments via petitioning. This proposal would contribute to more direct democracy. Regarding the concrete implementation of this reform, one could borrow useful insights from numerous state examples regarding petitioning for amendments of state legislation and constitutions.

In 18 states voters are allowed to initiate a proposed amendment of the state constitution through petitioning. Those petitions must be signed by a certain percentage of voters, ranging from three to 15 per cent of designated voting groups which differ from state to state. In most states, the threshold is eight or ten per cent of the total votes cast for Governor in the last gubernatorial election. Moreover, nine states have a territorial distribution requirement for the signatures. Consequently, a reform of Article V in order to provide the possibility of petitioning for proposing federal amendments could for example be carried out by imposing a requirement of eight or ten per cent of the total votes cast for Governor in the last gubernatorial election in at least one half of the states. However, this is only one possible proposal. Other proposals are imaginable to implement such a reform for which inspiration can be found in state constitutional tradition. Nevertheless, one has to be wary to impose too strict requirements. In some states the requirements for petitioning are so strict that this option has almost never been successfully used.

One could also advocate to introduce more direct democracy by entrusting the initiative to call a proposing national convention to the People. Currently, four states explicitly allow citizens to take the initiative to petition for putting a question on the ballot asking whether the People want to call a proposing constitutional convention to amend the state constitution. This is not an overwhelming number of states, but they may serve as examples for introducing popular initiative to call a national proposing convention. Although Akhil Amar relies on a non-exclusive reading of Article V to defend that Congress would be obliged to call a proposing convention if a simple majority of American voters so petitioned,119 an explicit amendment of Article V seems favourable in this regard. A threshold lower than a majority of the voters also seems recommendable, as it would be more in line with constitutional tradition in the states.

First, Florida requires that such a petition is signed by 15 per cent of the electors in each of one half of the congressional districts and of the state as a whole based on the last preceding election of presidential electors.120 Although in Florida more signatures are required to call a proposing national convention than to propose an amendment,121 a simple majority is sufficient to approve the question on the ballot. The latter is less than the required supermajority of 60 per cent on the ballot for a popular initiative proposing an amendment. Secondly, in Montana the petition has to be signed by 10 per cent of the qualified electors of the state, including 10 per cent of the qualified electors in each of two-fifths of the legislative districts.122 Thirdly, Article III, Section 1 of North Dakota’s Constitution allows for calling a constitutional convention without mapping out the rules of the game. Fourthly, in South Dakota the call for a proposing constitutional convention may be initiated by a petition signed by 10 per cent of the qualified voters that cast a vote for Governor in the last gubernatorial election.123

Currently, Congress can choose the required manner and threshold for ratification: approval by three-fourths of the state legislatures or by conventions in three-fourths of the states. Nevertheless, one could consider adding the option of a national convention to ratify proposed amendments. However, the current option of ratifying state conventions seems more advisable, as it brings the debate closer to the People and raises the chance that the interests of the constituents are taken into account. Nonetheless, one should consider opting for more direct democracy with regard to the final approval of constitutional amendments, namely a ratifying referendum.124 In this regard, one can invoke the Preamble of the US Constitution, stating ‘We, the People’ instead of ‘We, the States’, and one can rely on constitutional tradition in the states in order to introduce popular referenda in the federal amendment process. Popular referenda were unknown in 1787, but times have substantially changed.125 Some people may insist on involvement of the state level by state legislatures or state conventions as an essential part of federalism. Nonetheless, it is doubtful that the federalism argument can deprive the People of the right to alter themselves what they have established and ordained.

Ratification by referendum is undeniably an indispensable part of constitutional tradition on the state level. All states, except Delaware, require a popular vote after the proposal of constitutional amendments by the state legislature.126 Moreover, only Florida (in principle a 60 per cent vote and two-thirds for a new State tax or fee) and New Hampshire (two-thirds) substantially depart from the state tradition of a majoritarian voting rule for constitutional referenda by requiring a supermajority vote.

In 18 states, voters can themselves initiate a proposal to amend the Constitution via petitioning. Once the percentage or number of voters required to sign the petition is achieved, the proposed amendment has to be put on the ballot in all those 18 states for ratification. In 13 states a simple majority of the voters is sufficient. In addition, three states require a certain percentage of votes cast in the election in addition to a simple majority voting yes on the particular amendment. Only Florida and Illinois127 require a supermajority of 60 per cent voting on the proposed amendment.

Finally, 24 out of the 40 states where the Constitution explicitly provides how a constitutional convention can be called explicitly require a simple majority vote for ratification of proposed amendments, two states require a 60 per cent vote, and New Hampshire requires a two-thirds vote. The other 13 state constitutions do not explicitly regulate which majority of the voters is required. Most of those 13 state constitutions only mention that the proposed amendments ought to be put on the ballot. In the other states, those amendments are in principle brought before the voters even if this is not explicitly required by the state constitution.

Bruce Ackerman has argued to explicitly amend Article V of the US Constitution in order to introduce the option of a national referendum. He proposed the following amendment process. A President in his/her second term may propose amendments to the US Congress. Then, if two-thirds of both Houses approve the proposal, it requires 60 per cent of the voters in two successive Presidential elections to ratify the amendment.128 This procedure might, however, be too onerous. The constitutional tradition in the States might constitute an argument for introducing popular ratification of proposed amendments with a simple majority of those voting—that is, not of all who are eligible or registered to vote129—in one election.130

Despite Akhil Amar’s defence of a non-exclusive reading of Article V in favour of the right of a simple majority of the People to amend the Constitution, it is recommendable to explicitly amend Article V in order to include direct democracy.131 I disagree with Henry Monaghan’s argument that federalism and the role of the states—as inter alia embedded in James Madison’s notable quote in Federalist No. 39 that ‘[the Constitution is] neither wholly national nor wholly federal’132—should exclude direct democracy via national referenda.133 One could ensure a balanced territorial distribution of the required ratification across the states in order to avoid an unjustified veto power of the smallest states or an unjustified prevalence of the most populous states. One could for example require ratification by a majority in three-fourths of the states or by a number of states representing at least three-fourths of the US voters in the preceding national election.

C.Simple Majority for Popular Votes

As shown above, direct democracy in the form of referenda is inherently part of state tradition. Therefore, the latter could inspire to add this option to the federal amendment process and thereby give the Constitution back to the People. Consequently, the question has to be posed whether a simple majority vote would be sufficient or a supermajority vote should be required. Constitutional tradition in the states constitutes an important argument in favour of the former option. It is relevant to look at the threshold required by the state constitutions for the popular vote with regard to:

(1)approval of amendments proposed by the state legislature;

(2)ratification of amendments proposed by popular initiative;

(3)approval of the question asking if a constitutional convention should be organised; and

(4)ratification of amendments proposed by a constitutional convention:134

(1) After an affirmative vote by a state legislature to propose an amendment, the proposal is referred to the ballot in 49 states. State tradition overwhelmingly requires simple majorities for the popular ratifying vote. Only Florida (in principle a 60 per cent vote and two-thirds for a new State tax or fee) and New Hampshire (two-thirds) require a supermajority vote.

(2) Eighteen states allow popular initiative of their citizens to propose amendments via petitions. In 13 out of those 18 states a simple majority of the voters is sufficient to approve the proposed amendment. Moreover, three states require a simple majority vote on the proposed amendment and a certain percentage of votes cast in the election. Only two states require a supermajority. Florida requires a supermajority vote of 60 per cent and in Illinois ratification can be achieved by 60 per cent of the votes on the amendment or a majority of voters in the election. Again, constitutional tradition in the states favours simple majority voting rules.

(3) 40 state constitutions explicitly prescribe how a constitutional convention can be called. Three different options can be distinguished: an automatic ballot question, initiative by the state legislature, and popular initiative. Firstly, state constitutions in 14 states provide an automatic ballot question at regular time intervals. In 12 out of those 14 states, a simple majority vote of the People is sufficient to approve the question and Oklahoma’s constitution does not mention which majority is required. Only Illinois demands a supermajority vote of 60 per cent of those voting on the question or a majority of those who cast a ballot for any office in the election.135 Secondly, 26 out of the 27 states in which the state legislature can autonomously put a question on the ballot for calling a constitutional convention, require a simple majority vote by the People for ratification. Only Illinois requires a 60 per cent supermajority of the votes on the question or a majority of the voters who cast a ballot for any office in the election. Finally, in four states the question can be put on the ballot through petitioning. In each of those four states, a simple majority vote can approve the call for a convention.

(4) 24 out of the 40 state constitutions explicitly prescribing how a constitutional convention can be called explicitly require a simple majority vote for ratification of proposed amendments, while only three states require a supermajority vote. Minnesota and Florida require a 60 per cent vote, while New Hampshire requires a two-thirds vote. The other 13 states constitutions do not explicitly prescribe which majority of voters is required to vote yes for ratification.

In conclusion, a popular vote is almost inseparably linked with a simple majority voting rule. Akhil Amar has been vigorously defending the right of a simple majority of the People to alter the Constitution.136 Although this may scare some people,137 many US citizens are already subjected to a majoritarian voting rule for amendments to their state constitution. Moreover, on the federal level there is a ‘safety in numbers’. In contrast, one state is more likely to be dominated by a majoritarian view which may entail negative consequences.138 Finally, not only a tyranny of a majority, but also a tyranny of a minority can arise, which may block positive and reasonable reforms favoured by a strong majority.

In 1787, there was a lack of useful examples at the state level providing a detailed amendment procedure which provided direct involvement of the People. Moreover, the federal amendment process has never been improved since its adoption 228 years ago. Constitutional tradition in the states has, however, evolved and has generated an extremely rich, though often ignored, source of (experiments with) amendment procedures. For instance, popular referenda were unknown in 1787, but times have substantially changed. Presently, state constitutional tradition clearly champions direct democracy and majoritarian voting rules.

The analysis of the 50 state constitutional amendment processes in this contribution could serve as a starting point for a better informed normative debate about constitutional amendment procedures on the state and the federal level. If one reflects on the possible implementation of state experiments on the federal level, one has to take into account the different features of the federal context, such as a higher likelihood of factionalism. Nevertheless, state tradition could be an important argument in favour of adding more direct democracy to the federal constitutional amendment process through the introduction of initiative petitioning and ratifying referenda. A thorough analysis of state constitutionalism shows that a popular vote is almost inseparably linked with a simple majority voting rule. If one would opt for the introduction of a ratifying referendum at the federal level, it is recommendable to ensure a balanced territorial distribution of the required ratifiying vote across the states in order to avoid an unjustified veto power of the smallest states or an unjustified prevalence of the most populous states.

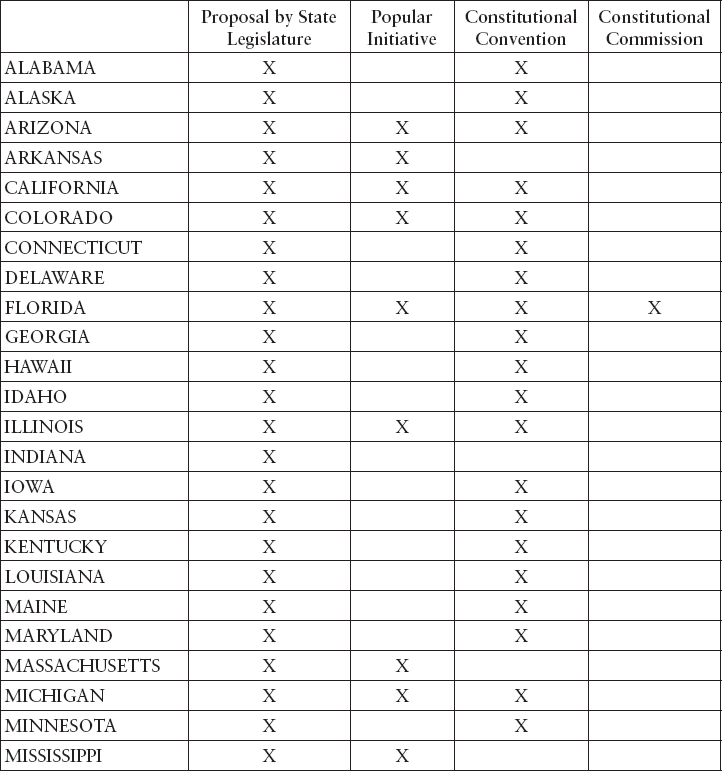

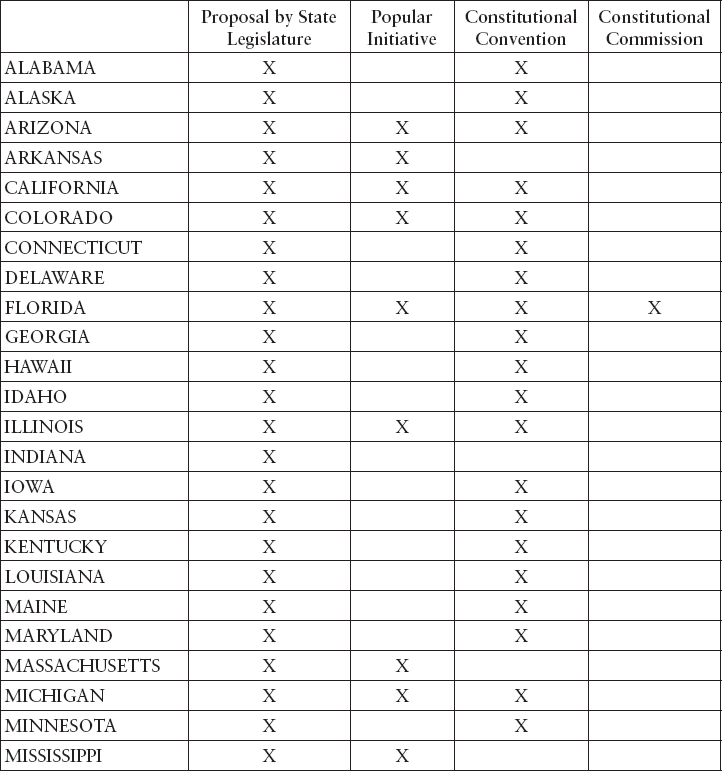

VI.ATTACHMENT: METHODS FOR CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT PROVIDED BY THE STATE CONSTITUTIONS

1The author would like to thank the organisers and participants of the Works-In-Progress Symposium at Yale Law School (10 April 2013), the World Congress of Constitutional Law in Oslo (18 June 2014), the Annual Conference of the Cambridge Journal of International and Comparative Law (8 May 2015), and the IACL-BC Workshop on Comparative Constitutional Amendment at Boston College Law School for granting him the opportunity to present and discuss drafts of the paper. Moreover, the author would like to express special gratitude for the stimulating discussions with Akhil Amar, Bruce Ackerman and Dieter Grimm. Finally, the author would like to thank Richard Albert for inviting him to publish early findings on the I-CONnect blog.

2New State Ice Co v Liebmann [1932] 285 US 262, 311.

3See below Section II(A).

4See below (n 10).

5AR Amar, America’s Constitution: A Biography (Random House, 2005) 292.

6MB Rappaport, ‘Reforming Article V: The Problems Created by the National Convention Method & How to Fix Them’ (2010) 96 Va L Rev 1509, 1512–3 (invoking the uncertainty of a runaway convention in order to explain why states find it unattractive to call a national proposing convention).

7MC Hanlon, Note, ‘The Need for a General Time Limit on Ratification of Proposed Constitutional Amendments’ (2000) 16 J L & Politics 663; see also M Kalfus, Comment, ‘Time Limits on the Ratification of Constitutional. Amendments Violate Article V’ (1999) 66 U Chi L Rev 437.

8DS Lutz, ‘Toward a Theory of Constitutional Amendment’ in S Levinson (ed), Responding to Imperfection: The Theory and Practice of Constitutional Amendment (Princeton University Press, 1995) 237, 265. See also S Levinson, Our Undemocratic Constitution (Oxford University Press, 2006) 21 and 160–5.

9cf Amar (n 5) 298.

10Based on the data of the census of 2010, available at <http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-01.pdf> accessed 1 August 2016. In according to the census of 2010, the 13 states with the smallest population number together have 13,725,340 citizens, which approximately represents 4.44% of the total US population (308,745,538). It should, however, be noted that principally a simple majority of the delegates in a state convention or of the members of the state legislature, thus approximately representing 2.22% of the US population, are sufficient to ratify an amendment. See P Suber, ‘Population Changes and Constitutional Amendments: Federalism Versus Democracy’ (1987) 20 U Mich J L Reform 409 (denouncing the three-fourths ratification requirement and noting how population changes de facto altered the amendment process of Art V).

11Rappaport (n 6) 1511–13.

12See, eg, DR Dow, ‘The Plain meaning of Article V’ in S Levinson (ed), Responding to Imperfection: The Theory and Practice of Constitutional Amendment (Princeton University Press, 1995) 117; HP Monaghan, ‘We the Peoples, Original Understanding, and Constitutional Amendment’ (1996) 96 Colum L Rev 121, 127; LB Orfield, The Amending of the Federal Constitution (University of Michigan Press, 1942) 39; LH Tribe, ‘Taking Text and Structure Seriously: Reflections on Free-Form Method’ in Constitutional Interpretation’ (1995) 108 Harv L Rev 1221, 1233; JR Vile, ‘Legally Amending the United States Constitution: The Exclusivity of Article V’s Mechanisms’ (1991) 21 Cumb L Rev 271.

13Some might argue that the People only retain the inalienable right to entirely abolish the Constitution, as opposed to just alter it. I reject this view, inter alia, because abolishing the entire constitution and replacing it with the same constitution with minor changes is de facto the same as an alteration.

14Amar (n 5) 292; Y Roznai, ‘Amendment Power, Constituent Power, and Popular Sovereignty: Linking Unamendability and Amendment Procedures’, in this volume (arguing that the Constitution cannot restrict the primary constituent power); see also Th Pereira, ‘Constituting the Amendment Power: A Framework for Comparative Amendment Law’ in this volume (analysing the relationship between popular sovereignty and amendment power).

15Amar (n 5) 295.

16See below Section III(C).

17Amar (n 5) 287–88 (explaining in more detail how the states were able to amend their first constitutions).

18NJ Const of 1776, Art XXIII. A member of New Jersey’s legislator only had to swear in his oath to not alter certain provisions of the Constitution.

19SC Const of 1778, Art XLIV.

20Del Const of 1776, Art 30; Md Const of 1776, Art LIX.

21Ga Const of 1777, Art LXIII.

22Pa Const of 1776, s 47; Mass Const of 1780, part II, ch VI, Art X; NH Const of 1776, part II.

23Amar (n 5) 288–9.

24J Elliot, The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution (1836) Vol II, 432.

25See The Federalist No 43 (James Madison).

26Amar (n 5) 285–86.

27See, eg, BA Ackerman, ‘The Storrs Lectures: Discovering the Constitution’ (1984) 93 Yale LJ 1013, 1017–23.

28See the supremacy clause in Art VI US Const.

29Amar (n 5) 289.

30See above, n 18.

31See also Amar (n 5) 289.

32See below Section III(C).

33BA Ackerman, We The People: Transformations (Harvard University Press, 1998) 80.

34RS Hoar, Constitutional Conventions: Their Nature, Powers, and Limitations (Little, Brown, and Company, 1917) 39–40.

35Amar (n 5) 296; AR Amar, ‘Philadelphia Revisited: Amending the Constitution Outside Article V’ (1988) 55 U Chi L Rev 1043, 1054–55 and 1069.

36Amar (n 35) 1056–60; AR Amar, ‘The Consent of the Governed: Constitutional Amendment Outside Article V’ (1994) 94 Colum L Rev 457, 489–94 (developing an intra-textual argument based on the Preamble, the First, Ninth, and Tenth Amendments); ibid (1994) at 457 and 481–7. Contra Vile (n 12) 271.

37Levinson, Undemocratic Constitution (n 8) 11–2.

38ibid 177 (endorsing Akhil R Amar’s non-exclusive reading of Article V and the legality of a ratifying national referendum by simple majority vote).

39BA Ackerman, We The People: Foundations (Harvard University Press, 1991) 185–86.

40ibid 50–52. See also DA Strauss, The Living Constitution (Oxford University Press, 2010) 121–23 (referring to the New Deal and McCulloch v Maryland as ‘extratextual amendments’).

41VJ Bryce, The American Commonwealth, Vol 1 (Liberty Fund, 1995) 312 (1888).

42FA von Hayek, ‘Competition as a Discovery Procedure’ in FA von Hayek (ed), New Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics, and the History of Ideas (Routledge, 1978) 179–90.

43WE Oates, ‘An Essay on Fiscal Federalism, Journal of Economic Literature’ (1999) Journal of Economic Literature 1120, 1123.

44KS Strumpf, ‘Does Government Decentralization Increase Policy Innovation?’ (2002) 4 Journal of Public Economic Theory 207, 208.

45See JJ Dinan, The American State Constitutional Tradition (University Press of Kansas, 2006) 29–63 (analysing the debates in the state conventions to explain why the more flexible state amendment processes differs from the onerous federal process).

46See generally GE Connor and Chr W Hammons, The Constitutionalism of American States (University of Missouri Press, 2008).

47JJ Wallis, ‘NBER/University of Maryland State Constitution Project’ <http://www.stateconstitutions.umd.edu/index.aspx> accessed 10 April 2015.

48Dinan (n 45) 30–31.

49See G Benjamin, ‘Constitutional Amendment and Revision’ in GA Tarr and RF Williams (eds), State Constitutions For The Twenty-First Century (State University of New York Press, 2006) Vol 3, 177, 185.

50Arizona, Arkansas, Minnesota, Missouri, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South-Dakota.

51Okla Const, Art XXIV, para 1.

52NM Const, Art 19, para 1.

53Alabama, Florida, Illinois, Kentucky, Maryland, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio.

54Neb Const, Art XVI, para 1.

55Alaska, California, Colorado, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Michigan, Mississippi, Montana, Texas, Utah, Washington, West Virginia, Wyoming.

56SC Const, Art XVI, para 1.

57Pa Const, Art XI, para 1.

58Delaware, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, Nevada, New York, Pennsylvania, South-Carolina, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, Wisconsin.

59Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, Nevada, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Wisconsin.

60Del Const, Art XVI, para 1.

61Vt Const, S 72.

62Conn Const, Art XII.

63Haw Const, Art XVII, para 3.

64NJ Const, Art IX.

65Pa Const, Art XI, para 1.

66Or Const, Art XVII, para 2.

67Alaska, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Montana, New Jersey, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Washington, Wyoming.

68Tenn Const, Art XI, para 3.

69Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin. In order to submit a proposed amendment to a special election, Nebraska’s constitution imposes a supermajority of 80%. Similarly, Oklahoma’s constitution requires a two-thirds vote of the state legislature to bring a proposed amendment before the voters at a special election.

70Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming.

71La Const, Art XIII, para 1.

72Neb Const, Art XVI, para 1.

73Tenn Const, Art XI, para 3.

74Utah Const, Art XXIII, para 1.

75Ill Const, Art XIV, para 1.

76Fla Const, Art XI, para 7.

77See Orfield (n 12) 177–80 (discussing proposals advocating to allow a proposal of amendments by popular initiative on the federal level and referring to constitutional practice in the states).

78Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, and South Dakota. See KK DuVivier, ‘By Going Wrong All Things Come Right: Using Alternative Initiatives to Improve Citizen Lawmaking’ (1995) 63 U Cin L Rev 1185.

79See Ariz Const, Art XXI, para 1; Cal Const, Art II, para 9; Colo Const, Art V, para 1; Fla Const, Art XI, para 3; Ill Const, Art XIV, para 3; Mass Const, Art XLVIII, The Initiative, IV, para 2; Miss Const, Art XV, para 273; Mich Const, Art XII, para 2; Mo Const, Art III, para 50; Mont, Art XIV, para 2; Neb Const, Art III, para 2; Nev Const, Art 19, para 2; ND Const, Art III, para 9; Ohio Const, Art II, section 1a: Okla Const, Art V, para 2; Or Const, Art IV, para 1; SD Const, Art XXIII, para 1.

80Ark Const, Art 5, para 1; Fla Const, Art XI, para 3; Mass Const, Art XLVIII, General Provisions, II; Miss Const, Art XV, para 273; Mo Const, Art III, para 50; Mont, Art XIV, para 2; Neb Const, Art III, para 2; Nev Const, Art 19, para 2; Ohio Const, Art II, s 1a.

81Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nevada*, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, and South Dakota.

* Voters in Nevada need to approve constitutional amendments by initiative with a simple majority vote in two separate elections in order to become part of the state constitution (Nev Const, Art 19, para 2).

82Mass Const, Art XLVII, IV, paras 3–5.

83Miss Const, Art XV, para 273.

84Neb Const, Art III, para 4.

85Fla Const, Art XI, para 5.

86Ill Const, Art XIV, para 3.

87Ill Const, Art XIV, para 3.

88Mass Const, Art XLVII, II, para 2.

89Mass Const, Art XLVII, IV, paras 3–5.

90Miss Const, Art XV, § 273.

91Duggan v Beermann, [1994] 245 Neb. 907, 515 NW 2d 788.

92Nev Const, Art 19, para 2.

93Okla Const, Art V, para 2.

94Alaska, Hawaii, Iowa, New Hampshire, Rhode Island.

95In Michigan, Art XII S 2 of the state Constitution stipulates ‘At the general election to be held in the year 1978, and in each 16th year thereafter and at such times as may be provided by law, the question of a general revision of the constitution shall be submitted to the electors of the state. If a majority of the electors voting on the question decide in favour of a convention for such purpose, at an election to be held not later than six months after the proposal was certified as approved, …’ (italics added).

96Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Missouri, Montana, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma.

97Okla, Art XXIV, para 2.

98Ill Const, Art XIV para 1.

99Alabama, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, Tennessee, West Virginia, Wisconsin.

100Illinois, Nebraska.

101California, Colorado, Delaware, Idaho, Kansas, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, South-Carolina, Utah, Washington, Wyoming.

102Alabama, California, Colorado, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming.

103Alabama, California, Colorado, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky*, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska**, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, Nevada***, North Carolina, Ohio, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming.

* In Kentucky, an approval requires a simple majority voting on the proposition in favour for calling a convention and the total number of votes cast for the calling of the Convention needs to be equal to one-fourth of the number of qualified voters who voted at the last preceding general election in this State (KyConst, S 258).

** In Nebraska, a simple majority of the electors voting on the proposition is only sufficient if the votes cast in favour of calling a convention shall not be less than 35% of the total votes cast at the election (Neb Const,Art XVI para 2).

*** Article XVI, Section 2 of Nevada’s Constitution proclaims that a majority of the electors voting at the election need to vote in favour of calling a Convention in order to approve it. Moreover, it states that in determining what constitutes a majority of the electors voting at the election, reference has to be made to the highest number of votes cast at such election for the candidates for any office or on any question.

104Ill Const, Art XIV, para 1.

105Alaska Const, Art XIII, para 2.

106Connecticut, Georgia, Louisiana, Maine, South Dakota, Virginia.

107Fla Const, Art XI, para 4; Mont Const, Art XIV, para 2; ND Const, Art III, para 1; SD Const, Art XXIII, para 2.

108Akhil Amar relies on a non-exclusive reading of Article V of the federal Constitution to defend that US Congress would be obliged to call a proposing convention if a simple majority of American voters so petitioned. Amar (n 35) 1065 (supplementary invoking the First Amendment’s right of the people to petition the Government).

109Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, New Hampshire, New York, Ohio, Rhode Island.

110Office of the Vermont Secretary of State, ‘Statewide Referendum. 1969: Constitutional Convention Referenda’, 1, 2 (Vermont Secretary of State, 6 July 2006) <https://www.sec.state.vt.us/media/59733/1969.pdf> accessed 10 April 2015.

111California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Hawaii*, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, Wisconsin.

* In Hawaii, an approval of a proposed amendment or revision can be achieved by a majority vote of at least 50% of all the votes generally cast in the election, or by at least 30% of all the registered voters in the state at the time of the election in case of a special election (Haw Const,Art XVII,para 2).

112Minnesota and Florida.

113Alabama, Alaska, Delaware, Kentucky, Maine, Montana, Missouri, Nevada, Ohio, South Carolina, West-Virginia, Washington, Wyoming.

114See B Buzzett and SJ Uhlfelder, ‘Constitution Revision Commission: A Retrospective and Prospective Sketch’ The Florida Bar Journal 4 (April 1997) 22, 22; Dinan (n 45) 300, n 7.

115Fla Const, Art XI, para 5.

116Fla Const, Art XI, para 2.

117Fla Const, Art XI, para 6.

118See, eg, J W Burgess, Political Science and Comparative Constitutional Law: Vol 1 Sovereignty and Liberty (Ginn & Company, 1902) 137, 151–52 (repudiating ‘the artificially excessive majorities’ and suggesting a proposal of amendments by two successive sessions of Congress via simple majority vote and a ratification by a simple majority of state legislatures); WS Livingston, Federalism and Constitutional Change (Clarendon Press, 1956) 248–53 (proposing several proposals to reform the amending procedure); Orfield (n 12) 168–221 (noting numerous proposals made in the 1920s and 1930s to improve Art V); JR Vile, The Constitutional Amending Process in American Political Thought (Praeger, 1992) 137–56 (discussing the views of Progressive Era commentators on the amending procedure); SM Griffin, ‘The Nominee is … Article V’ (1995) 12 Const Comment 171; T Lynch, ‘Amending Article V to Make the Constitutional Amendment Process Itself less Onerous’ (2011) 78 Tenn L Rev 823; Rappaport, n 6) 1509.

119Amar (n 35) 1065.

120Fla Const, Art XI, para 4.

121Fla Const, Art XI, para 3: ‘Signed by a number of electors in each of one half of the congressional districts of the state, and of the state as a whole, equal to 8% of the votes cast in each of such districts respectively and in the state as a whole in the last preceding election in which presidential electors were chosen.’

122Mont Const, Art XIV, para 2.

123SD Const, Art XXIII, para 2.

124See Orfield (n 12) 192–203; ibid at 192: ‘The chief proposal for the alteration of the amending process to receive serious consideration in the past two decades has been that for a referendum.’

125Orfield (n 12) 192.

126See above Section III(A)(iii) for more details, including the relevant states and their state constitutional provisions.

127In Illinois, an approval of a proposed amendment can be obtained by 60 per cent of the people voting on the amendment or a majority of those voting in the election (Ill Const, Art XIV, para 3).

128Ackerman (n 39) 54–55; Ph J Weiser, Note, ‘Ackerman’s Proposal for Popular Constitutional Lawmaking: Can It Realize His Aspirations for Dualist Democracy?’ (1993) 68 NYUL Rev 907 (criticising Ackerman’s proposal and advocating for deliberation).

129Amar (n 35) 1064, n 78.

130Ackerman would probably not accept this as a threshold for a constitutional moment of higher law-making, because he would probably not consider a vote of the People during one election as a sustained moment of higher law-making.

131See Amar (n 5) 295–97.

132The Federalist No 39, at 246 (James Madison) (Clinton Rossiter edn, 1961): ‘If we try the Constitution by its last relation to the authority by which amendments are to be made, we find it neither wholly national nor wholly federal. Were it wholly national, the supreme and ultimate authority would reside in the majority of the people of the Union; and this authority would be competent at all times … to alter or abolish its established government. Were it wholly federal, on the other hand, the concurrence of each State in the Union would be essential to every alteration that would be binding on all.’

133Monaghan (n 12) 121 (criticising Akhil R Amar by invoking federalist papers of Madison and Hamilton about the role of the states).