Navarrete in the Rioja wine region has 11 bodegas (wineries) (Stage 5)

Navarrete in the Rioja wine region has 11 bodegas (wineries) (Stage 5)

When a ninth-century Galician shepherd found the long-buried body of the Apostle James in a remote corner of north-west Spain, he could not have envisaged that his discovery would lead to a huge pilgrimage with hundreds of thousands of people making their way every year across Europe to visit his find – or that this pilgrimage would witness not one but two periods of popularity, with 500 years between them. The first pilgrimage, which ran between the ninth and sixteenth centuries was a hard journey. Medieval peregrinos (pilgrims) would travel thousands of kilometres to Santiago with no maps or guides, in basic clothing, braving the weather, dangerous animals, thieves and polluted drinking water to gain absolution from their sins by touching what believers claim to be the tomb of Santiago (St James), a disciple of Jesus Christ. When they reached Santiago, they had to turn around and retrace the hazardous journey. They could be away from home for up to a year, with no way of contacting family and friends. Significant numbers would never return home, some dying en-route and others settling down for a new life in northern Spain.

The journey is much easier for modern pilgrims. They can travel in weatherproof clothing on well-waymarked trails, drinking safely from countless drinking fountains that are tested frequently to guarantee water purity, with neither wolf, bear nor robber in sight. Every night they can stay in basic but comfortable albergues (pilgrim hostels) and consume good-value filling food and wine from pilgrim menus in a wide choice of restaurants. They can use mobile phones to call home every night and post online pictures of themselves on their journey. When they reach Santiago, they can fly home effortlessly in a few hours.

The degree of hardship may have changed, but the journey is still one of discovery, both of new places and of the inner self. The route followed may have altered slightly but it still has the same name, El Camino de Santiago (The Way of St James) or usually just ‘The Camino’. Medieval pilgrims either walked or travelled on horseback. Modern pilgrims still walk, but very few use a horse. Those that do ride nowadays favour a bicycle and take approximately two weeks to complete the journey across northern Spain from St Jean to Santiago and it is for these cycling pilgrims that this guide has been written.

Rich medieval pilgrims travelled on horseback, nowadays only a handful use animal power (Stage 5)

There is more than one pilgrim route to Santiago, but the most popular in medieval times and again today is the Camino Francés, named for the large number of French pilgrims who followed this route. Pilgrims started at many points throughout France or further afield, using different routes that converged upon St Jean-Pied-de-Port at the foot of the lowest and easiest pass over the Pyrenees into Spain. Their approximately 800km route from St Jean to Santiago follows a generally east–west trajectory, south of and parallel with the Cantabrian mountains. Beyond the Pyrenees the trail undulates through Navarre then crosses the wine-producing region of Rioja. After steadily ascending then descending into Burgos, the route reaches and crosses the northern tip of the meseta, a vast area of rolling high-level chalk downland that occupies much of central Spain. After León, the forested Montes de León and fertile Bierzo basin are crossed before the rolling green hills and valleys of Galicia are reached. The Camino ends at the great religious city of Santiago de Compostela, where the tomb of St James housed inside an 11th-century cathedral is the ultimate destination of the pilgrimage.

The Camino is not just a two-week ride through northern Spain. About half of walking peregrinos make the pilgrimage for religious reasons. For them the journey can become a voyage of self-discovery with the opportunity to meet and talk to like-minded believers, visit and perhaps take communion in ancient churches and cathedrals, while having time to contemplate the spiritual side of their lives. Others, including many cyclists, make the journey for exercise and recreation. For them the challenge is to successfully cycle 800km including traverses of the Pyrenees and the Montes de León. Yet more are attracted by the cultural side of the Camino, seeking to visit stunning cathedrals, historic abbeys and ancient city centres. The appetite is catered for too, with a wide variety of local foods accompanied by good-quality wine. In summary, the Camino has something for everyone. ¡Buen Camino! (have a good journey).

The earliest known inhabitants of northern Spain (from around 800,000BC) were pre-hominids and Neanderthals, whose remains have been discovered at Atapuerca near Burgos (Stage 7). Later, successive waves of Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age civilisations arrived from Central Asia via western Europe. The last of these were Indo-European speaking Celtic tribes who arrived in Spain during the sixth century BC.

The Romans came to Spain in 218BC, initially to conquer the Carthaginians who had settled along the Mediterranean coast. From here Roman control spread slowly north and west in campaigns against Celtic tribes but it was not until 19BC that all of Iberia came under Roman rule. The Romans involved local tribal leaders in government and control of the territory. With an improved standard of living, the conquered tribes soon became thoroughly romanised. Indeed, the Roman province of Hispania became an important part of the Roman Empire, with three emperors being born there: Trajan (ruled AD98–117), Hadrian (AD117–38) and Marcus Aurelius (AD161–80). The VII legion was settled in Legio (León, Stage 11) while nearby gold mines made Asturica Augusta (Astorga, Stage 12) a rich and prosperous town. Roads were built linking cities across Iberia, including one across northern Spain, south of the Cantabrian mountains from Pompaelo (Pamplona, Stage 2) to Brigantum (near Coruña) via León and Astorga that 1000 years later would be partly followed by the Camino. The Romans knew this as Via Lactea (Milky Way) as it was said to follow the stars to Finis Terrae (the end of the world) on the Atlantic coast of Galicia.

Castromaior castle was an Iron Age camp later used by the Romans (Stage 16)

During the fifth century AD, the Romans came under increasing pressure from Germanic tribes from the east who invaded Gaul (France) and moved on into Hispania. Roman rule ended in AD439 with the Romans allowing the Christian and partly romanised Visigoths to take control of most of Spain after a brief interlude of Suevi (Swabian) rule.

Despite consolidating power by defeating other Germanic tribes and inheriting the well-established levers of Roman rule, Visigoth rulers did not have the same grip on power that their predecessors held. Internal disputes were common with periodic civil wars, assassinations, usurpations of power and free-roaming warlords all destabilising the state. Like other civilisations of the Dark Ages, the Visigoths left little in the way of architecture or art and few written documents, resulting in the soubriquet ‘invisigoths’. After AD585, when they conquered Galicia, they controlled all of Iberia apart from the Basque country, Asturias and Cantabria on the north coast.

From AD618, when the prophet Mohamed fled from Mecca to Medina, Islam spread rapidly through the Middle East and along the north African coast, arriving in what is now Morocco by the end of the seventh century. In AD711, the Moorish army of the Umayyad Caliphate crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and invaded southern Spain where they defeated a Visigoth army at the Battle of Guadalete. King Roderic and many nobles were killed, leaving Spain with no army and no leadership. This allowed the Moors to capture much of the country unopposed.

The small independent kingdom of Asturias, on the north coast, became the focus of resistance to Moorish occupation. In AD722, a Moorish army confronted a small Asturian force led by Don Pelayo occupying a narrow gorge at Covadonga in the Cantabrian mountains. Here, against all odds, the Moors suffered their first defeat in Spain. This Asturian victory is regarded as the beginning of a Christian fightback against the Moors which became known as the Reconquista (Reconquest).

Other victories followed with the boundaries of Asturias being extended slowly west into Galicia, east into Cantabria and south over the Cantabrian mountains into León. Christian legend tells of a victory at Clavijo (AD834) which played a major role in the development of the Camino. The apostle James, wielding a sword and riding a white horse, is said to have appeared at the head of the Christian army and led them to victory in his name. This vision became Santiago Matamoros (St James the Moor-slayer), an iconic figure portrayed all along the Camino and a rallying cry for soldiers in the Christian armies.

As the Reconquista pushed the Moors south, the cities of Pamplona, Burgos and León were freed from Moorish rule, becoming capitals of independent kingdoms in Navarre, Castile and León. The capital of Christian Spain moved south too, first from Oviedo to León, then to Valladolid and eventually to Madrid after the Moors were driven from central Spain in 1212. The Moors held on in Andalucía for nearly 300 years until 1492 when the fall of Granada ended 781 years of Muslim involvement in Spain.

San Juan de Ortega monastery church (Stage 7)

When Christopher Columbus, an Italian from Genoa employed by the Spanish crown, discovered land in the Caribbean in 1492, he unwittingly changed the economic fortune of Spain. Spanish colonisation of large parts of the New World led to discoveries of vast lodes of gold and silver which made Spain the richest country in Europe. On the death of Ferdinand II (1516), the Spanish crown passed to Charles V, a Habsburg who became Holy Roman Emperor. During his reign and that of his son Phillip II, Spain entered a golden age controlling large parts of Europe with overseas colonies in the Americas, Africa and Asia. Unfortunately, with the exception of Burgos and León which sat on north–south trade routes, this prosperity was not shared along the Camino where the decline of the pilgrimage led to economic depression and falling populations.

After 1700, the Spanish crown passed to the Bourbons, the French royal house. For the next 100 years Spanish economic and political policies were closely connected with France. The empire survived until 1807, when French emperor Napoleon entered Spain intent on capturing Portugal and bringing it into his Continental System in order to isolate his greatest threat, Britain. The ensuing Peninsular War (1808–14) between Britain (defending its Portuguese ally), and France and Spain caused much devastation across Iberia. Lack of central government caused South American colonies to take control of their own affairs, which after the war led to unilateral declarations of independence throughout the New World.

Weakened by war and unable to maintain its empire, 19th-century Spain declined from the richest country in Europe to one of the poorest. Apart from development in the regional enclaves of Catalonia and the Basque country, Spain missed much of the Industrial Revolution that swept Europe. The country was politically unstable with numerous constitutions, three internal wars (the Carlist Wars of 1833–39 and 1872–76 and the Civil War of 1936–39), two abdications, two volatile republics, military coups, regional uprisings, bombings and assassinations. The Civil War, a vicious confrontation between right and left, regionalism and centralisation, clerical and secular power divided the country almost equally between supporters of an incipient republic and the nationalism of Generalísimo Francisco Franco. Most of the area passed through by the Camino was a conservative part of Spain that generally supported the nationalist cause. Indeed, Burgos (Stage 7) was Franco’s headquarters during the conflict.

Victory for the nationalists was followed by a long period of tightly controlled stability while the country recovered slowly from the trauma. When Franco died (1975), Spain reverted to a constitutional monarchy and reinstated a degree of regional autonomy. After joining the European Union in 1989, an influx of development funding led to a dramatic increase in economic activity with new motorways and railways criss-crossing the country, new airports and new factories. City centres have seen major developments. Spain suffered in the financial crash of 2007 but is now recovering. The country was a founding member of the Euro zone, while the Shengen agreement allowing the free movement of people has resulted in open borders with France and Portugal.

St James was one of the 12 apostles of Jesus Christ. The bible (Acts 12:1–2) tells us that he was beheaded in Jerusalem, probably in AD44. Before he was killed, James had travelled to Spain to spread Christian teaching, although this does not appear in contemporary accounts. After his death his body was returned by boat to Spain where it was taken ashore at Padron in Galicia, carried inland and buried on a remote hillside.

Nearly 800 years later in AD813, a Galician shepherd was led by a star to discover the remains of a long-dead body buried in a field. He reported his find to the local bishop who identified the bones as the remains of St James. A church built over the grave was rebuilt many times, evolving into a great cathedral surrounded by the medieval city of Santiago de Compostela (St James of the Field of Stars). This discovery was a godsend for the leaders of the Reconquista who adopted James as the figurehead of their fight against the Moors and patron saint of Spain. A slow trickle of pilgrims, who believed that by touching the bones of St James they could gain absolution of their sins and thus ensure entry to heaven, began making their way to Santiago.

The body of St James is kept in a casket in Santiago cathedral (Stage 18)

By AD900 the Moors had been driven from a long strip of land across northern Spain immediately south of the Cantabrian mountains. This territory became an uninhabited no-man’s land with Christian Spaniards reluctant to repopulate the area due to fear of Moorish return. The transit of pilgrims, mostly from France crossing Spain on their way to Santiago, was encouraged by the Kings of Navarre and León as a way of promoting settlement. Spaniards moved in to service the pilgrims, while some of the pilgrims themselves, appreciating the opportunity to cultivate empty lands, settled in the area on their way back from Santiago. Towns and cities grew-up along the route with inns, hostels, churches and hospitals to serve the pilgrims and stone bridges enabling them to cross rivers.

For the following three centuries the number of pilgrims continued to grow. A significant boost came when King Alfonso VI of León and Castile (ruled 1065–1109) invited the reformed Benedictine monastery of Cluny in Burgundy to participate in the construction and management of monasteries and churches along the route. These were often built by French craftsmen in a distinctive French-influenced style. Chivalrous orders, including the Knights Templars who built a large castle at Ponferrada (Stage 13), were given duties to protect pilgrims. The first guide to the route, the Codex Calixtinus thought to be by the monk Aymeric Picaud, was written about 1140 and it is believed that by the end of the 12th century 250,000 pilgrims were making the journey annually. The numbers began declining in the 14th century after the Black Death (1346–53) swept through Europe killing nearly half the population and, although the pilgrimage remained popular, 13th-century levels of participation were not matched until the 21st century.

Martin Luther, a German monk and professor of theology, published his 95 theses in 1517. These criticised many practices of the Catholic church including two elements central to the Camino: the idolisation of relics and granting of indulgences. Luther’s teaching and that of contemporary theologians such as Erasmus, Knox and Calvin instigated a Protestant Reformation which took hold rapidly across northern and western Europe. This growth of Protestantism further reduced the number of pilgrims setting off for Santiago. In France the church became divided between Catholic devotees of the status quo and Protestant Huguenots who supported the Reformation. A series of devastating religious wars broke out starting in 1562, culminating in 1595 with holy war between France and Spain where the inquisition ensured the continuing supremacy of Catholic teaching. International pilgrim travel became difficult and dangerous; by the end of the 16th century the medieval pilgrimage was over.

For three centuries few pilgrims made the journey to Santiago. Pilgrim infrastructure along the Camino fell into disuse and ruin. In 1884 Pope Leo XIII declared that the bones at Santiago were indeed those of St James, but this did little to re-awake interest in the pilgrimage. Two world wars and the Spanish Civil War continued to make the journey difficult and unappealing. Post-Second World War interest was fuelled by the publication in 1957 of The Road to Santiago by Anglo-Irish academic Walter Starkey, which brought the Camino to an English-speaking audience.

The most significant element in the revival of the Camino was the work of Dr Elías Valiña Sampedro, an academic from Salamanca University who was also parish priest at O Cebreiro (Stage 14). He wrote his thesis on the medieval pilgrimage and in 1984 took a pot of paint and started marking the route with the yellow arrow waymarks that have now become synonymous with the Camino. He persuaded local parishes to re-open long-closed pilgrim albergues and local government to improve track surfaces and divert the route away from busy roads, work which has continued since his death in 1989. The route you will follow is very much Dr Sampedro’s legacy. Do take a few minutes to visit his monument beside O Cebreiro church and thank him for his efforts.

Dr Elías Valiña Sampedro, who was the priest at O Cebreiro (Stage 14), waymarked the Camino by painting yellow arrows

Coverage in popular culture is now widespread, including The Way (2010), a film written and directed by Emilio Estevez and starring Martin Sheen. This and much other publicity has dramatically increased the number of peregrinos reaching Santiago from under 1000 in 1985, to 55,000 in 2000, and over 300,000 (22,000 of whom were cyclists) in 2017. The Pilgrim Reception Office in Santiago (https://oficinadelperegrino.com) publishes daily statistics showing pilgrim arrivals, detailed by nationality, mode of transport, start point of the pilgrimage and motivation. These show that approximately 180,000 pilgrims used the Camino Francés with 50,000 travelling the whole route either passing through St Jean-Pied-de-Port or starting in Navarre. Other popular starting points are León, Ponferrada and O Cebreiro. However, the most popular of all is Sarria (Stage 15), 113km from Santiago. The 80,000 walkers who start here are attracted by a provision in the rules for awarding the Compostela certificate for completing the route (the present-day equivalent of a medieval absolution). This provides that certificates will be given to walkers who complete 100km to Santiago and Sarria is the first place outside this distance that can be reached by public transport. Cyclists and horse-riders are required to travel 200km in order to qualify for a Compostela, giving a start point in Ponferrada (Stage 13).

In 1178, Pope Alexander III introduced the concept of Jubilee Years for St James, years when the saint’s day (25 July) falls on a Sunday. In these years the Door of Pardon at the rear of Santiago cathedral is open and pilgrims who pass through it earn pardon for their sins. During the medieval Camino, a few other churches along the route were granted the same privilege, thus allowing sick and dying pilgrims who could not reach Santiago to obtain pardon. Jubilee Years are popular times to undertake the pilgrimage and in 2010 more than 100,000 extra pilgrims travelled the Camino. Similar increases are anticipated in future Jubilee Years (2021, 2027 and 2032) with up to 500,000 pilgrims expected during 2021.

Throughout the Camino you will encounter many statues and representations of St James. These fall into two sharply contrasting groups. The peaceful side of James bringing the gospel to Spain is represented by Santiago Peregrino in the form of a cloaked pilgrim with a wooden staff and often wearing a scallop shell. By contrast, Santiago Matamoros is a mounted figure on a horse using a lance or sword to kill Moors, representing the warrior James leading the fight for Christianity.

Santiago Matamoros, the aggressive image of Santiago the Moor-slayer, Burgos cathedral (Stage 7)

When Dr Sampedro started marking a route for the modern Camino, he tried to identify and follow the way used by medieval pilgrims. This caused many problems. Long stretches had become asphalt surfaced roads, requiring peregrinos to walk along the side of often busy highways. As numbers grew, regional and provincial councils addressed this problem by either providing sendas (gravel trails parallel with the road) or diverting the route onto tracks through neighbouring fields. Today these trails and tracks form the backbone of the Camino followed by walking pilgrims. They are classified as bridleways and are legally accessible by horse riders and cyclists in addition to pedestrians. This route, which is best suited for mountain bikes, provides the basis for the main route in this guide, although there are a few places where a combination of steep gradient and rough track conditions make it necessary for cyclists to deviate slightly from the walked Camino.

The roads, which the modern Camino has moved away from, provide the base for an alternative road route, which apart from one short stretch is entirely asphalt surfaced. These two routes are fully described in this guide where the Camino for mountain bikes based on the walkers’ route is referred to as the ‘camino route’ and the road alternative is called the ‘road route’. There are many shared stretches and, on every stage, both routes start and finish at the same point.

From St Jean-Pied-de-Port on the French side of the Pyrenees, Stage 1 climbs up and over the mountains using one of the lowest Pyrenean passes to reach Roncesvalles abbey in Spain, a place with historic connections going back to Roland in AD778. Descent on Stage 2 into the Arga valley takes the route to Pamplona in Navarre, a partly Basque-speaking city famous for the annual running of the bulls. Continuing across Navarre (Stages 3–4), the Camino climbs over a windswept ridge then passes through the ancient religious centre of Estella before reaching the wine-producing city of Logroño in the Rioja region. Stage 5 passes close to some of the highest quality vineyards in Spain, while Stages 6–7 climb steadily up and over the forested Montes de Oca and bare limestone Sierra de Atapuerca before descending into El Cid’s city of Burgos.

Between Burgos and León (Stages 8–11) the route crosses the northern tip of the meseta, a vast area of rolling high-level chalk downland that occupies much of central Spain. This was a difficult area for medieval pilgrims, with long distances between villages, very little water and no shade which still offers a challenge today. The small towns and villages passed through are undergoing an economic revival brought by the modern Camino after 400 years of stagnation and population decline. León, just beyond the mid-point of the journey, is a popular place for a short break from cycling. This former Roman city and early capital of medieval Spain has outstanding buildings representing 900 years of architectural development from a Romanesque basilica that holds a mausoleum of former monarchs, through to a French-Gothic cathedral and a Renaissance former monastery that is nowadays the most ornate Spanish parador (luxury hotel) to a modernist Gaudí-designed private palace (Appendix G contains a brief summary of Spanish architectural styles).

The Camino crosses the meseta, an area of high-level downland with little shade (Stages 8–12)

Stage 12 runs through the Páramo, a fertile area irrigated by water from the Cantabrian mountains, to Astorga, a former Roman town that prospered from nearby gold mines. Stage 13 climbs into the Maragateria and over the forested Montes de León, part of the Cantabrian mountains, then descends steeply to the Knights Templar town of Ponferrada. Stage 14 crosses the fertile Bierzo basin then climbs steeply to reach O Cebreiro perched high in the mountains on the edge of Galicia. The final four stages (Stages 15–18) pass through rolling Galician green hills and valleys. The Camino ends at Santiago de Compostela, a city of monasteries, churches and ancient streets surrounding the pilgrims’ ultimate destination, the tomb of St James housed inside a great 11th-century cathedral.

The north-eastern border of Spain is formed by the Pyrenees mountains. Composed of a core of granite covered by limestone outer flanks, the range was pushed up by a collision between the Iberian and European tectonic plates approximately 50 million years ago. South of the Pyrenees is the Ebro basin. Originally connected to the Bay of Biscay, this basin was raised by the plate collision then filled with sands, gravels and clays brought down from the mountains by riverine erosion.

The centre of Spain is a high chalk plateau of rolling downland, known as the meseta (tableland) which covers much of the region of Castile y León. This is an area of large arable farms typically growing wheat and sunflowers, with a few small villages, little groundwater and no shade. The Camino (Stages 8–12) crosses the northern part of this plateau. Modern irrigation schemes bringing water down from the Cantabrian mountains have enhanced the agricultural fertility of the western meseta.

Flanking the northern edge of the meseta, the limestone Cantabrian mountains run east–west parallel with the Bay of Biscay. For much of the route they can be seen on the northern horizon until Stage 13 when the route climbs over a subsidiary range known as the Montes de León. The Bierzo basin, between the Montes de León and the Galician massif, is a highly fertile area of sedimentary deposits with an attractive microclimate where vines, fruit and vegetables are grown. The last four stages (14–18) run through the Galician massif, an area of low rounded granite mountains and hills, originally heavily forested but now a mixture of woods and pastoral farms.

While several small mammals and reptiles (including rabbits, hares, squirrels and snakes) may be encountered scuttling across the track, and deer seen in forests and fields, this is not a route where you will encounter unusual wildlife. There are bears and wolves in the remote parts of the Cantabrian mountains, but not near the Camino.

Storks’ nests on the church bell tower at Puente del Castro (Stage 11)

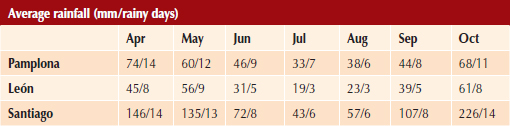

The routes can be cycled at any time of year, although they are best followed between April and October when the days are longer, the weather is warmer and there is no chance of snow. July and August are very hot and very busy, with spring and autumn the most pleasant times to make the journey.

Both routes have been broken into 18 stages averaging approximately 43km per stage. A fit cyclist, cycling an average of 80km per day using roads or 55km per day off-road should be able to complete the road route in 10 days and the camino route in two weeks. A faster cyclist averaging 100km per day could complete the road route in eight days. There are many places to stay along both routes making it possible to tailor daily distances to your requirements. When planning your schedule, allow at least a day in Santiago at the end of your pilgrimage to obtain your Compostela and visit the cathedral. If you want a mid-journey break, León is an attractive city with many things to see.

The camino route mostly follows well-surfaced gravel tracks with frequent undulations, although there are a few rough stages. This is best cycled on a cross-trail bike, a simplified type of mountain bike designed for riding both gravel trails and roads with a wide range of gears (typically a rear cassette with 11–36 teeth and front chainrings of 26/36/48 teeth), off-road tyres and disc brakes. Front suspension is beneficial as it absorbs much of the vibration. It is passable on a hybrid (a lightweight but strong cross between a touring cycle and a mountain bike) provided this is set up with low gearing and off-road tyres.

Apart from two short sections of gravel surface on Stage 5 between Logroño and Santo Domingo de la Calzada, the road route uses asphalt surfaced roads throughout. It is cyclable on all types of road cycle (hybrid, tourer, racing bike) provided panniers can be fitted. If you use a mountain bike or cross-trail for the road route it should be set up with road tyres and have the suspension locked out.

Straight handlebars, with bar-ends enabling you to vary your position regularly, are recommended. Make sure your cycle is serviced and lubricated before you start, particularly the brakes, gears and chain. Your choice of tyres is as important as the cycle. For the camino route you should use knobbly off-road tyres. However, these are not suitable for the road route where you need a good-quality touring tyre with a deeper tread and a slightly wider profile than you would use for everyday cycling at home. To reduce the chance of punctures, choose tyres with puncture resistant armouring, such as a Kevlar™ band.

An alternative to taking your own bicycle is to rent one to collect when you arrive. Hire companies in Pamplona, Burgos and Santiago can deliver a cycle to your start point and collect it after your journey. Most offer good-quality bikes with back-up repair coverage. Many walkers use bag transfer services and these can be used by cyclists to complete the Camino without panniers.

To stay in albergues, obtain discounted entry to many monuments along the route and most importantly obtain your Compostela in Santiago, you will need pilgrim credentials also known as a pilgrim passport. National Camino organisations, including the Confraternity of St James in Britain (www.csj.org.uk), issue credentials and provide advice for pilgrims. Other national confraternities are listed in Appendix D. If you leave home without a credential, you can pick one up at the Pilgrim Information Office in St Jean-Pied-de-Port or at Roncesvalles abbey. Credentials are available to all self-propelled peregrinos (walkers, cyclists and horse riders but not motorists or motor-bikers) irrespective of religious faith.

Pilgrim credentials need to be stamped every day to qualify for a Compostela

As you travel along the route, the credential should be stamped with an official stamp and dated at least once a day (twice a day for cyclists who start in Ponferrada). These stamps can be obtained from albergues, hotels, town halls, tourist offices, churches and cathedrals and even some restaurants. Upon arrival in Santiago, the stamped credential should be presented to the Pilgrim Reception Office (33 Rúa das Carretas, Santiago 15705, open 0800–2100) where it will be inspected and your Compostela issued. This is a certificate showing you completed the Camino and is the modern-day successor to the medieval indulgence although it no longer offers to pardon your sins or grant entry to heaven. Beware, long queues often form at the office and it can take several hours before you are seen.

St Jean-Pied-de-Port is the terminus of a local railway line from Bayonne, served by four trains per day that carry cycles and take about one hour to reach St Jean. From London, St Jean can be reached in a day either by flying to Biarritz then cycling to Bayonne and continuing by train, or by travelling by train throughout.

Getting from Biarritz airport to Bayonne station

Follow exit road from Biarritz airport and turn R at roundabout onto main road (Ave d’Espagne, D810). Continue ahead for 4.5km, going over three more roundabouts. At fourth roundabout, turn L (third exit, Allées Paulmy, sp Centre-Ville). At end, bear R following one-way system (Ave Léon Bonnat), passing public gardens L. Turn L on bridge over river Nive and continue ahead on second bridge over river Adour. Bear L to reach roundabout in front of Bayonne station (7.5km).

Eurostar trains from London St Pancras to Paris Gare du Nord carry cycles as do some (but not all) of the TGV trains from Paris Gare Montparnasse to Bayonne. If you leave London by 08.00, cycle across Paris from station to station (6km) to catch a TGV from Montparnasse before 13.00, you will arrive in Bayonne in time to connect with the last train to St Jean arriving about 19.00. If you leave London on a later train you will need to overnight in Bayonne and catch the first train next morning, arriving in St Jean before 09.00.

Eurostar trains from London, that take under two and a half hours to reach Paris via the Channel tunnel, carry up to six cycles per train: two fully assembled plus four dismantled bikes packed in specially designed fibreglass bike boxes provided by Eurostar. Bookings, which open six months in advance, must be made through EuroDespatch at St Pancras (tel +44 (0)344 822 5822). Prices vary from £30–£55 depending on how far ahead you book and whether your cycle is dismantled or fully assembled. Cycles must be checked in at the EuroDespatch centre beside the bus drop-off point at the back of St Pancras station, at least 60 minutes before departure. If you need to dismantle your bike, Eurodespatch will provide tools and packing advice. Leave yourself plenty of time for dismantling and packing. In Paris Gare du Nord, cycles can be collected from Geoparts baggage office which can be reached by a path L of platform 3. More information at www.eurostar.com.

Crossing Paris: Gare du Nord to Gare Montparnasse

After arrival in Paris you need to cycle through the heart of Paris from Gare du Nord to Gare Montparnasse using a mixture of dedicated cycle tracks beside wide boulevards, marked cycle lanes and contra-flow cycling along one-way streets. Go ahead opposite main entrance to Gare du Nord along Bvd de Denain (one-way street with contra-flow cycling permitted). At end turn half L (Bvd de Magenta, cycle track R) and follow this SE. Turn R just before number 77 (Rue de Faubourg St Denis) and continue straight ahead doglegging R and L past Porte St Denis archway into Rue St Denis. Where this becomes one-way with contra-flow cycling continue ahead for 1.25km to reach major crossroads beside number 12. Turn R (Rue de Rivoli) then first L (Rue de Lavandières Ste Opportune) and continue ahead to reach T-junction on banks of river Seine. Turn L (Quai de la Mégisserie) and R over river on Pont au Change bridge (3km).

Continue over second bridge (Pont St Michel) and fork R (Place St Michel, becoming Rue Danton). Cross Bvd St Germain and turn R beside road. Soon turn L (Rue de l’Odéon) and fork R (Rue de Condé). Turn second R (Rue St Sulpice) and continue ahead past St Sulpice church and square with fountain (both L) into Rue du Vieux Colombier. Turn L (Rue de Rennes) at traffic lights and continue for 1km. Bear R beside Tour Montparnasse L to reach Gare Montparnasse L (6km).

From Paris Gare Montparnasse, there are TGV high-speed trains approximately every two hours to Bayonne. Most of these carry up to four cycles which must be booked in advance at the same time as booking your passenger ticket. Cyclists travel with their cycles in a dedicated second-class compartment at one end of the train. Bookings are made through SNCF, www.oui.sncf.com.

Houses in St Jean-Pied-de-Port overlooking the river Nive (Stage 1)

There are airports at Pamplona (Stage 2), Logroño (Stage 4), Burgos (Stage 7) and Léon (Stage 11) but none of these has direct flights to the UK; a connecting flight is necessary through Madrid, Barcelona or Frankfurt.

These four cities also have railway stations and there are other stations at Frómista (Stage 9), Sahagún (Stage 10), Astorga (Stage 12), Ponferrada (Stage 13) and Sarria (Stage 15). The only part where a railway parallels the Camino is between Sahagún and Astorga via Léon (Stages 11–12). In Spain neither AVE high-speed trains nor regular long-distance trains carry bicycles, although medium distance and regional trains do have bike spaces. Cycle carriage is free on these trains, but you must reserve a space before you travel.

The easiest way to return home from Santiago to the UK with your cycle is by plane. Santiago airport, 12km from the city centre and passed on Stage 18, has regular flights to many European cities. La Coruña airport, one hour from Santiago by hourly trains which carry cycles, also has flights to various airports. Airlines have different requirements regarding how cycles are presented and some, but not all, make a charge which you should pay when booking as it is usually greater at the airport. All require tyres partially deflated, handlebars turned and pedals removed (loosen pedals beforehand to make them easier to remove at the airport). Most will accept your cycle in a transparent polythene bike bag, however, some insist on the use of a cardboard bike box.

In Santiago, Velocípedo bicicletas (Rúa de San Pedro 23, tel +34 981 580 260, www.elvelocipedo.com) can supply bike boxes and offer a packing service (€21 or €45 including taxi to airport). An unusual but reliable way to get your cycle home is by post using the Spanish correos (post office) Paq Bicicleta service. They have two offices in Santiago – the central post office, Rúa do Franco 4, or a branch inside the Pilgrims’ Reception Office (Rúa das Carretas 33) – who will organise packing and despatch your bike to any overseas address. Cost to the UK is €90. This may seem expensive, but with airlines charging up to €70 to carry a cycle, plus the cost of the bike box and airport taxi, it can be cheaper than flying it home yourself. Should you not complete the whole route, they can deliver your cycle home from most intermediate towns on the Camino.

You can return home by train, but it is a complicated three-day journey. Neither the one daily direct train from Santiago to Irun on the French border, nor the AVE high-speed trains that link Santiago with Madrid via Valladolid and Madrid with Paris, carry cycles. The only route possible is to catch a RENFE regional train to La Coruña and a local train to Ferrol. From there FEVE narrow gauge trains run along the north coast of Spain. These slow trains stopping at all stations take two days to reach Bilbao, requiring an overnight stop in either Oviedo or Santander (there are pilgrim albergues in both cities). From Bilbao, Euskotren services run via San Sebastián to Irun for another overnight stop. From Irun you can catch an SNCF TGV train to Paris and Eurostar to London.

There are two alternatives to travelling all the way by train. One is to use FEVE to reach Santander or Bilbao then catch a ferry across the Bay of Biscay to Britain or Ireland. Brittany Ferries (www.brittany-ferries.co.uk) operate six sailings per week between Spain and Plymouth or Portsmouth in southern England with two per week to Cork in the Republic of Ireland. The second is to travel by Alsa bus (www.alsa.es) from Santiago to Bilbao then continue either by ferry to Portsmouth or by train via San Sebastián and Irun as described above. There are two buses per day (one daytime, one overnight) taking between 9 and 12 hours depending upon the route, carrying up to four cycles per departure. Alsa has a ticket agent inside the Santiago pilgrim reception office.

The camino route is fully waymarked throughout with yellow arrows, scallop shells, waymarks, stone pillars and Camino signposts. These waymarks are so frequent that if you travel for more than 500 metres without seeing a waymark of some kind, you have almost certainly taken a wrong turn and need to go back.

The Camino is waymarked with a variety of symbols, mostly in yellow or blue

The road route is less frequently waymarked and where signs do occur they are often placed in the middle of long stretches of straight road, acting more as a confirmation that you are on the correct route rather than an indication of which route to follow. In some places white arrows painted on the road show directions for cyclists. While useful, these are inconsistent and cannot be relied upon. In general, the road route follows four Spanish national roads: N-135, N-111, N-120 and N-547. In some regions, where motorways have taken traffic off these main roads, they have been reclassified as regional roads and renumbered accordingly. This is particularly the case in Navarre, where the N-111 has been renumbered NA-1110, reverting to N-111 when it reaches Logroño.

It is possible to cycle both routes using only the maps in this book, particularly the camino route which is waymarked throughout. If you want a series of maps at a larger scale and that show a wider area than that covered by the strip maps, IGN España (the Spanish equivalent of the Ordnance Survey) produce a boxed set of 11 sheet maps at 1:50,000 while Michelin publish a map booklet at 1:150,000 (map 161). Camino Guides publish a map booklet that has hand drawn maps of varying scale (each stage is drawn to fit one page with scales differing from map to map and most confusingly between parts of the same map), and while these maps are not particularly accurate nor all embracing, the booklet does show the location of, and give details about, all accommodation opportunities en-route.

Les Amis du Chemin de St Jacques office issues pilgrim credentials (Stage 1)

For the whole route there are a wide variety of places to stay overnight. The stage descriptions identify places known to have accommodation, but new properties open every year so the list is by no means exhaustive. An updated list of albergues and other accommodation for the whole Camino can be obtained from Les Amis du Chemin de St Jacques office in St Jean-Pied-de-Port and the Confraternity of St James in London also produces an annual pilgrim guide with up-to-date accommodation listings plus an occasional cycling supplement intended for use with its guide. Tourist information offices can provide lists of local accommodation in all categories but unlike in northern Europe do not provide a booking service. Booking ahead is seldom necessary, except in high season (July and August). The search engine www.booking.com has the widest range of accommodation in northern Spain. Most properties are cycle friendly and will find you a secure overnight place for your pride and joy. Prices for all kinds of accommodation are lower than in the UK.

Albergues (marked with a white A on a blue sign on the outside of the building) are the most numerous and popular type of accommodation along the Camino and are a good place to stay if you want to meet and converse with other pilgrims. Albergues are everywhere, even tiny hamlets may have two or more. Many new ones have opened in recent years, some too new to appear on accommodation lists. There are three kinds: municipal (run by the local government), religious (run by churches, monasteries and other religious organisations) and private. The average price is between €7–€12 for a dormitory bed in a municipal or religious albergue, slightly higher for private albergues which often have individual rooms as well as dormitories. However, the large number of new albergues opened in recent years provide intense competition, which is keeping prices down. Some religious albergues have no quoted price and ask instead for donations. As a guide, you should donate the same as you would pay for a municipal albergue. There are 11 hostelling international youth hostels, but four are in or around Pamplona and so they are not well spread. In practice, youth hostels are similar to albergues.

Albergue Gaucelmo in Rabanal del Camino is run by British volunteers from the Confraternity of St James (Stage 13)

Albergues usually close during the day, opening around 1600. In high season (July and August) some busy municipal and religious refuges give preference to walkers and may not accept cyclists until after 1800. Lights out is at 2200, with many walking pilgrims rising before 0600 for an early start. Blankets are usually provided; all you need is a sleeping sheet and a towel. Many albergues have a cocina (kitchen) where you can prepare your own food, while some have a comedor (dining room) that serves a menú peregrino, a cheap fixed price meal. Almost all will provide a secure place to store your cycle.

These establishments provide accommodation in separate rooms, usually with private toilet and shower but sometimes cheaper hostels and pensions have shared facilities. Hotels (marked with a white H on a blue sign) vary from five-star properties to modest local establishments. At the top end there are five paradores, state-owned luxury hotels in restored historic buildings. Hostales (marked with white Hs on a blue sign) are smaller hotels and guest houses with fewer services. Most hotels and hostels offer a full meal service. Pensions (marked with a white P on a blue sign) provide simple accommodation, often using rooms in apartment buildings. A casa rural is a country guest house usually offering B&B and evening meals to guests.

Economic accommodation in albergues is so widely available that very few people choose to camp. Most campsites are aimed at longer stay holiday makers rather than overnighting pilgrims.

There are many places where peregrinos can eat and drink, varying from snack bars to Michelin-starred restaurants. English language menus are widely available along the Camino either printed or on chalkboards. Eating out in Spain is not expensive and almost every village will have at least one small restaurant offering a menú peregrino (set-price pilgrim meal including wine) at around €10, usually with long opening hours to suit walking peregrinos.

Local restaurants (comedores), frequented by working people rather than peregrinos, are often attached to bars or local inns. They are sometimes hard to spot, being just a door at the back of the bar that is only open at Spanish mealtimes (1400–1500, 2100–2300). Historically they had to offer a cheap filling menú del día (lunchtime set-price meal) consisting of three courses and a half bottle of wine, affordable to working men. Prices for the menú del día are similar to pilgrim meal prices but there will probably be only an à la carte menu in the evenings. If you are going to eat a la carte, you need to request la carta, asking for the menu will get you the set-price meal. Roadside restaurants (ventas) offer similarly priced food aimed at truck drivers and passing motorists. Cafeterias, mostly in towns and cities, generally offer platos combinados (single course, drinks not included) rather than a menú del día. These tend to be blander options (fish and chips, ham and eggs, etc) of a pan-European nature, but with similar prices.

Full service restaurants, sometimes attached to hotels, offer a la carte menus. They have a grading system (one–five forks) reflecting the price, variety and quality of food served.

If you want a series of quick snacks rather than a full meal, tapas bars provide a wide range of choice. In the larger cities (Pamplona, Logroño, Burgos, León, Santiago) large numbers of tapas bars are concentrated in a small area making an evening paseo (walk) from bar to bar trying different tapas an attractive alternative to sitting down to a restaurant set meal. Single portions (pinchos) and small filled bread rolls (bocadillos) are usually displayed on the bar counter while larger portions (raciones) can be ordered from the barman.

Tapas bars in all the major cities offer a wide variety of tapas

During the summer season, pop-up bars and restaurants spring up along the route. These serve food and drink from caravans, marquees, vans or basic wooden shelters; usually in the same place each year. They are often located where there are long distances between conventional refreshment providers such as the 12km stretch through the forested Montes de Oca between Villafranca Montes de Oca and San Juan de Ortega (Stage 7).

Traditional Spanish eating hours differ significantly from the rest of Europe. Breakfast (desayuno), usually nothing more than coffee and a croissant, is taken about 0900. Lunch (almuerzo) is late, usually between 1400–1500 while dinner (cena) is even later, between 2100–2300. Light snacks are consumed mid-morning while more substantial snacks, such as tapas, are taken in early evening.

This pattern of eating is not really suitable for pilgrims, who like to start early (often before 0700) and go to bed by 2200. Restaurants catering to pilgrims reflect this by offering early breakfasts, lunch between 1200–1400 and dinner from 1900 with a menú peregrino offered at both lunchtime and early evening. Full a la carte dinners are usually served after 2100.

Spanish cooking is generally Mediterranean in style with ample use of olive oil, garlic, tomatoes and other Mediterranean vegetables. While there are a number of regional specialities that you will encounter, much of the food offered in pilgrim menus is unadventurous and pan-Iberian in style. Most meals will start with soup, such as vegetable, ajo (garlic) or barley, or pasta. The most common main courses are chuletas de cerdo (pork chops) or pollo (chicken) followed by postre (dessert) of fruit, flan (cream caramel) or arroz con leche (rice pudding). Although it originated on the Mediterranean coast, paella, a dish of saffron rice, chicken and seafood, is widely available along the route. Other pan-Iberian dishes include tortilla Española (a thick omelette of eggs, potatoes and onions, cut into sections and often served cold as a bocadillo filling), jamón serrano (cured ham) and chorizos (spicy sausages).

Regional cuisine consists mainly of hearty dishes using local ingredients. Navarre is known for cordero (lamb), trucha con jamón (trout wrapped in ham) and menestra de verduras (vegetable stew), while in La Rioja look out for patatas a la Riojana (potatoes roasted with chorizo and red peppers). In León you will find morcilla (black pudding/blood sausage) while fabada (bean and pork casserole), which originates from nearby Asturias, is widely available. Galician dishes include caldo Gallego (turnip top, potato and pork stew) and a wide range of empanadas (savoury pies made with meat or tuna). However, the main emphasis of food in Galicia centres around vaca/ternera (beef/veal) and dairy products in the hills and mountains and pescado (fish) and mariscos (seafood) nearer the coast. The biggest selling fish are merluza (hake), bacalao (cod), salmón and dorada (bream). Among a wide selection of seafood, the most common are gambas (prawns), calamar (squid) and pulpo (octopus): Melide (Stage 17) is famed for its octopus. Vieiras a la Gallega (scallops cooked with ham, onions and tomato sauce) are served in a scallop shell, the symbol of the Camino. They provide a fitting final meal for your journey, especially when accompanied by albariño white wine from the nearby Rias Baixas and finished off with a slice of tarta Santiago (almond tart decorated with another Camino symbol, the Santiago cross, etched into its dusting of sugar).

To finish the meal there are a wide variety of cheeses. Manchego, Spain’s biggest selling cheese, is ubiquitous but there are also local cheeses to try. Cabrales (made from goats’ milk blended with sheep and cows’ milk) comes from Asturias while Roncal is a smoked sheep milk cheese from Navarre. Galicia is dairy country, producing Ulloa (flat) and Tetilla (breast shaped), both soft cows’ milk cheese. Other Galician cows’ milk cheese includes Cebreiro (hard, mild) and San Simón (smoked, orange coloured, conical).

Galicia is a land of rolling green hills with a mix of dairy farms and forest (Stages 15–18)

Viticulture was re-introduced to northern Spain by the French after the Moors had been expelled and the country has been a vino (wine) drinking country ever since. Well-bodied vino de mesa tinto (red table wine) is the staple tipple of most Spaniards, although blanco (white), rosado (rosé), espumoso (sparkling) and fortified wines are also available. In recent years there has been a move away from heavy red wines to lighter varieties. Table wine is automatically included in set menus (including pilgrim menus), usually a half bottle or 250mm carafe per person. Do not worry if you do not drink wine, agua sin gas (still water) or agua con gas (sparkling water) are available as alternatives but as a bottle of water is about the same price as a cheap bottle of wine you will not get a discount.

The Camino passes through the country’s most renowned vineyard region in Rioja and neighbouring Navarre and other less well-known regions in León, the Bierzo and Galicia. In Rioja (Stage 5), tempranillo and garnacha grapes are used to produce mostly high-quality red wine, although production of white Rioja using viura and malvasía grapes is small but increasing. Vineyards around León (Stage 11) produce predominately red table wines while the Bierzo (Stage 14) produces softer red wine using mencía grapes and white wine with godello grapes. The cooler damper climate of Galicia (Stage 18) is suited to lighter wines than the rest of Spain, producing white wine from albariño grapes and some soft reds.

Consumption of cerveza (beer) is growing with sales doubling between 1976–2006. Light pils-style lagers predominate, mostly produced by multi-national brewers Heineken/Amstel/Cruzcampo and Carlsberg/Mahou/San Miguel and national brewer Estrella Damm. Two strengths are widely available, cerveza clásica (4.6 per cent alcohol) and cerveza especial (5.5 per cent). If you ask for a cerveza, you will usually be served bottled beer, if you want draught beer you need to order una caña. This is normally served in 200ml glasses, for a larger glass (400ml) ask for caña grande. In Navarre a caña grande is often called una pinta while in Galicia it is known as uno bock. Cidra (apple cider) is produced in northern Spain, mostly in Asturias. This is stronger than beer and so dry it will pucker your lips. Often served from casks, it is poured from height into small glasses in order to generate a slight spritz.

Since Spain joined the EU a lot of capital has been spent improving the quality of rural water supplies and connecting properties to mains water. As a result, tap water along the Camino is safe to drink and there is no health reason to purchase bottled water. There are many drinking water fountains along the route; most towns and villages have at least one and there are some in rural locations. These are tested by health authorities and marked whether or not they are safe to drink (agua no potable is not safe to drink!).

All the usual soft drinks (colas, lemonade, fruit juices, mineral waters) are widely available.

All cities, towns and larger villages passed through have grocery stores, often supermarkets, and most have pharmacies. Most villages have a panadería (bakery) that bakes fresh bread every day. Local shops typically open on Mondays to Saturdays 09.30–13.30 and 16.30–20.00, while larger stores, supermarkets and department stores are generally open 10.00–21.00, but there are local variations. Most shops are closed on Sundays.

The steep track up to Alto del Perdón with Pamplona in the distance (Stage 3)

Most towns have cycle shops with repair facilities equipped to repair and service all types of bike. Many will adjust brakes and gears, lubricate your chain and make minor repairs while you wait. Locations of cycle shops are shown in stage descriptions with full addresses listed in Appendix C, although this list is not exhaustive. Bicigrino is an association of cycle shops along the Camino that offer emergency repair services to peregrinos.

Spain switched from Spanish pesetas to euros in 2002. Almost every town has a bank and most have ATM machines which enable you to make transactions in English. However very few offer over-the-counter currency exchange and the only way to obtain currency is to use ATM machines to withdraw cash from your personal account or from a prepaid travel card. Contact your bank to activate your bank card for use in Europe or put cash on a travel card. Credit or debit cards can be used for most purchases, although albergues generally accept cash only. Travellers’ cheques are rarely used.

The whole route has mobile phone coverage. Contact your network provider to ensure your phone is enabled for foreign use with the optimum price package. International dialling codes are +44 for UK, +34 for Spain and +33 for France.

Almost all hotels, hostels, albergues and many restaurants make internet access available to guests, usually free of charge.

Voltage is 220v, 50HzAC. Spain uses standard European twin round-pin plugs.

The route is undulating with a few steep climbs, consequently weight should be kept to a minimum. You will need clothes for cycling (shoes, socks, shorts/trousers, shirt, fleece, waterproofs) and clothes for evenings and days off. The best maxim is two of each, ‘one to wear, one to wash’. Time of year makes a difference as you need more and warmer clothing in April/May and September/October when gloves and a woolly hat are needed for cold morning starts. A sun hat and sunglasses are essential. All of this clothing should be able to be washed en route, and a small tube or bottle of travel wash is useful.

In addition to your usual toiletries you will need sun cream and lip salve. You should take a simple first-aid kit. If staying in albergues, you will need a towel and torch (your cycle light should suffice).

One piece of decoration you may wish to attach to your panniers is a scallop shell. Medieval pilgrims brought such shells back from Santiago as ‘proof’ they had completed the journey. Modern peregrinos obtain such emblems early in their journey, often in St Jean-Pied-de-Port, and display them as a badge showing they are traversing the Camino.

Everything you take needs to be carried on your cycle. Unless camping, a pair of rear panniers should be sufficient to carry all your clothing and equipment, although if camping, you may also need front panniers. Panniers should be 100 per cent watertight. If in doubt, pack everything inside a strong polythene lining bag. Rubble bags, obtainable from builders’ merchants, are ideal for this purpose. A bar-bag is a useful way of carrying items you need to access quickly such as maps, sunglasses, camera, spare tubes, puncture kit and tools. A transparent map case attached to the top of your bar-bag is an ideal way of displaying maps and guidebook.

A fully loaded cycle at the start of the Camino in St Jean-Pied-de-Port (Stage 1)

Your cycle should be fitted with mudguards and bell. It should be capable of carrying water bottles and pump. Except in June and July, lights are essential as Spain has a late sunrise and you are likely to start the day cycling in the dark. Many cyclists fit an odometer to measure distances. A basic toolkit should consist of puncture repair kit, spanners, Allen keys, adjustable spanner, screwdriver, spoke key and chain repair tool. The only essential spares are two spare tubes. On a long cycle ride, sometimes on dusty tracks, your chain will need regular lubrication and you should either carry a can of spray lube or make regular visits to cycle shops. A strong lock is advisable. Cycle helmets are compulsory in Spain, but the law is only loosely enforced.

The route passes through three distinct weather zones. The Pyrenees and Cantabrian mountains have an Alpine climate with warm summers, cold winters and precipitation (rain in summer/snow in winter) at any time of year. Between these ranges, the high altitude meseta plateau has a continental climate (hot dry summers, cold wet winters). Spring and autumn mornings can be very cold before sunrise and gloves and woolly hat are essential. In Galicia, the climate is temperate oceanic with warm summers, mild winters and rain at any time of year.

In Spain and France cycling is on the right side of the road. If you have never cycled before on the right you will quickly adapt, but roundabouts may prove challenging. You are most prone to mistakes when setting off each morning. Spain is a very cycle-friendly country. Drivers will normally give you plenty of space when overtaking and often wait behind patiently until space to pass is available.

Although Spain is west of the Greenwich meridian, it uses Central European time making it one hour ahead of Britain. As far as natural light goes this is the ‘wrong’ time zone. As a result, on early spring and autumn mornings it remains dark until between 08.00 and 09.00. Most walkers start early, usually before 07.00, to avoid the heat of the day. As a result, they walk for several hours in the dark. Even with lights, this is not an option for cyclists where rough tracks and unlit walkers pose a major hazard. If you are cycling off-road on the camino route, do not start until it is bright enough to see the track clearly without lights. In contrast, it remains light well into the evening and you should have no difficulty reaching your overnight stop before dark.

The camino route is mostly on tracks shared with a large number of walkers. Relations between walkers and cyclists can become strained, with some pedestrians believing that cyclists are wrongly using footpaths (you are not, the track is a bridleway for walkers and riders!). To ease this tension, cyclists should always be polite to walkers. Use your bell when approaching pedestrians from behind. If they do not hear you, shout ‘Hola’ (hello) and travel slowly enough to take avoiding action if they step into your path. Many sections are on sendas, gravel tracks parallel to and beside main roads. Where these roads are quiet it is usually better for cyclists to use the road and leave the senda for pedestrians. On some of the hilly sections you will find rough and narrow rocky tracks. These can be slippery and dangerous to negotiate and are often filled with walkers picking their way slowly up or down the hill. As a result, they are not recommended for cyclists and this guide describes alternative routes that avoid such obstacles.

For many kilometres the Camino follows sendas beside main roads (Stage 9)

Most of the road route uses main roads. However, since the completion of the Spanish autopista (motorway) network, these roads are extremely quiet with very little traffic. Moreover, almost all Spanish main roads have a metre-wide asphalt-surfaced hard shoulder which doubles as a cycle lane. Cycling is prohibited on motorways.

Many city and town centres have pedestrian only zones. These restrictions are often only loosely enforced and you may find locals cycling within them, indeed many zones have signs allowing cycling. One-way streets in Spain often have signs permitting contra-flow cycling but in some cases you will need to dismount and walk your cycle.

No special injections or health precautions are needed for Spain, but it is advisable to make sure basic inoculations for tetanus, diphtheria and hepatitis are up to date. The greatest health risk comes from sunshine and heat, particularly crossing the meseta in July and August. Sun hat, sun screen, lip salve and plentiful supplies of water are essential. One particular irritation is from bed bugs in cheaper accommodation, but as bed bugs do not carry dangerous diseases their bites are an annoyance rather than a health risk. Spraying your bed sheet with permethrin before leaving home will give some protection, as will a specially treated fine-mesh undersheet, such as the Lifesystems bed bug sheet.

In the unlikely event of an accident, the standardised EU emergency phone number is 112. The entire route has mobile phone coverage. Medical costs of EU citizens in possession of a valid EHIC card are covered under reciprocal health insurance agreements, although you may have to pay for an ambulance and claim the cost back through insurance. At present it is uncertain whether EHIC arrangements will change when Britain leaves the EU.

In general, the route is safe and the risk of theft low. However, you should always lock your cycle and watch your belongings, especially in cities.

Travel insurance policies usually cover you when cycle touring but they do not normally cover damage to, or theft of, your bicycle. If you have a household contents policy, this may cover cycle theft, but limits may be less than the actual cost of your cycle. Cycling UK (previously known as the Cyclists’ Touring Club), www.ctc.org.uk, offers a policy tailored to the needs of cycle tourists.

There are 18 stages, each covered by separate maps drawn to a scale of 1:100,000. The camino route line is shown in red and the road route in blue. Short excursions to visit town centres or off-route points of interest are shown in orange. GPX files are available on Cicerone’s website at www.cicerone.co.uk/969/GPX.

Walking and cycling peregrinos mostly share the same trails (Stage 6)

After Sarria the Camino becomes very busy with ‘100km walkers’ who start in Sarria (Stages 16–18)

All places shown on the maps appear in bold in the route description. Distances shown are cumulative kilometres within each stage, while altitudes shown in metres (m) are measured in the centre of the town or village. The abbreviation sp stands for ‘signposted’. For each city/town/village passed an indication is given of facilities available (accommodation, albergue, youth hostel, refreshments, camping, tourist office, cycle shop, station) when the guide was written. This list is neither exhaustive nor does it guarantee that establishments are still in business. No attempt has been made to list all such facilities as this would require another book the same size as this one. For full accommodation listings, contact local tourist offices. Such listings are usually available online. There is a facilities summary table in Appendix A and details of tourist offices along the route are shown in Appendix B. Other useful contact details are given in Appendix E.

While route descriptions were accurate at the time of writing, things do change. Temporary diversions may be necessary to circumnavigate improvement works and permanent diversions to incorporate new sections of track. Where construction is in progress you may find signs showing recommended diversions, although these are likely to be in Spanish only.

While Castilian Spanish is the national language of Spain, regional languages are widely spoken in parts of the country and you will find Basque used in Navarre (Stages 1–4) and Galician in Galicia (Stages 15–18). In Navarre most towns have two names while in both these regions road signs are bi-lingual. In this guide, Castilian Spanish names are used throughout.

This guide is written for an English-speaking readership. Along the route of the Camino, most people working in the tourist industry speak at least a few words of English. However, any attempt to speak Spanish is usually warmly appreciated. The most common language used by peregrinos is English and you will find people of many nations communicating with each other in English. Appendix F contains a list of useful Castilian Spanish words.

Pop-up café between Parabispo and Peroxa (Stage 17)