“My personal challenge for 2016 is to build a simple AI to run my home and help me with my work. You can think of it kind of like Jarvis in Iron Man.

I’m going to start by exploring what technology is already out there. Then I’ll start teaching it to understand my voice to control everything in our home—music, lights, temperature and so on. I’ll teach it to let friends in by looking at their faces when they ring the doorbell. I’ll teach it to let me know if anything is going on in Max’s room that I need to check on when I’m not with her. On the work side, it’ll help me visualize data in VR to help me build better services and lead my organizations more effectively.”

Mark Zuckerberg, 3rd January 2016, via Facebook

Think about all of this computing power at our fingertips, all of this data and an increasingly smart collection of algorithms anticipating our needs and running interference for us. What would it be called? Until I come up with something better, I’m going with Life Stream, or maybe Life Cloud.

Life Stream is not a personal control panel similar to the one you have in Windows or the system preferences of OSX because it could be distributed across multiple devices and spaces. It’s not an interface as there could be dozens of individual interfaces across devices and embedded computer platforms. It might have a primary AI or agent in a decade or so that knows you and talks to other computers or even other humans on your behalf. It includes sensors and other programs that will monitor you, but you’ll willingly trade off that loss of privacy for the benefits it gives you, after all, it will be your private data. It won’t be one cloud account, it will be a collection of data subsets that only make sense to you, but are often essential for you personally. It could be considered your personal operating system although, as you’ll see later, I don’t think an OS analogy quite cuts it.

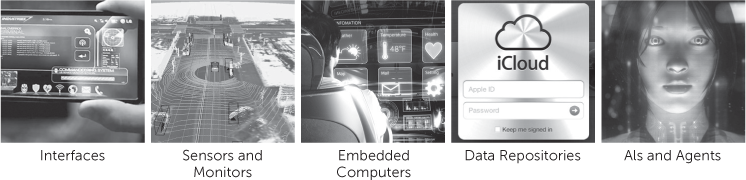

Here is the broad collection of elements that might make up your Life Stream:

In the movie Her, the intelligent operating system that Theodore Twombly (played by Joaquin Phoenix) uploads onto his computers and smartphone is called Samantha. Twombly ends up falling in love with the intelligence before the collection of OSs like Samantha merges into a hyperintelligence that goes off to another dimension. In the popular video game Halo, the hero’s personal AI is called Cortana, also the name of the AI assistant embedded in Microsoft Windows 10. In the video game, Cortana is an AI that helps fill in gaps of knowledge and hack into systems, etc. It is fairly specific in its goal of helping Master Chief complete his mission parameters but, at the same time, could easily fit the premise of an AI like Spike Jonze’s Samantha who fits into your daily life if the user in this instance wasn’t in a war against the Covenant!

There are two basic directions that this intelligence can go over the next ten years. We either centralise our lives around an Apple, Google or Microsoft cloud with some AI/agent built in (an enhanced Siri if you like) or we diverge from this considerably and have a separate collective agent/intelligence that is both device and platform independent. Supersets of data and analytics are, in my opinion, likely to diverge from an OS-owned model because they have to be more disparate. You can’t guarantee that your smart, autonomous vehicle is going to be running iOS with Siri. Thus, my guess is that it will work much like apps or social networks do today, sitting on top of devices or the various operating systems rather than being embedded. We’ll have to wait and see but there is value in an agent that works through any interface.

Regardless, the forces driving us to a Personal Stream and Interface are becoming increasingly clear. We have lots of devices, lots of screens and soon more data than we will logically be able to process personally or collectively as humans, so it will need to be curated by algorithms. Whatever curates all that data and allows us to interact will be the personal interface to these systems. Whoever cracks this problem will have a business bigger than Facebook by the middle of next decade. In fact, Facebook is hoping to be this business with its work on Facebook M, billed as a digital personal assistant.

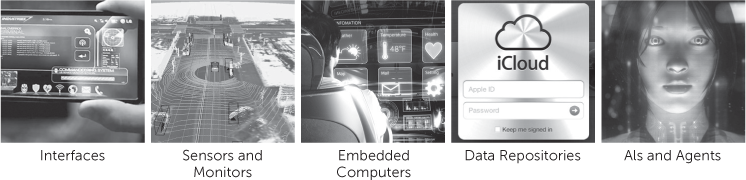

This software intelligence will have two broad capabilities: first, direct input, visualisation and feedback; second, collection, synthesis and agency.

Direct input is requesting an input or configuring software in a particular way, either via settings or training the software over time. Visualisation and feedback is whenever the software delivers feedback via a screen, an interface, haptic touch (vibration, force feedback, Force Touch, etc.) or through voice.

Collection of core data will occur every day through cameras, accelerometers, geolocation data points, iBeacons, payments ecosystems, apps and a broad range of sensors, both personalised and external. This data will go into pools of data both in your own cloud or personal repositories and external data stores where algorithms will look for certain behaviours, and will synthesize data for feedback.

The most interesting developments in personalisation will not just be in respect to visualisation and feedback but also in respect to these AI-based agents that will learn your behaviour, needs and typical responses and, over time, begin to act on your behalf. These agents and avatars will eventually morph into a personal AI that is akin to a super tech-savvy personal assistant. How will this evolve?

The first use of agency, which is already emerging, will be to carry out simple tasks as an extension of Siri or Cortana, such as the following:

• Siri, book me an Uber car home.

• Cortana, transfer $1,000 from my savings account onto my credit card.

• Siri, buy me $200 worth of bitcoin for my wallet.

• Jibo, order me the usual from my favourite Chinese restaurant (via Seamless).

• Siri, wake me up at 8 a.m. tomorrow.

• Cortana, start my engine and warm the car up to 70 degrees (linked to OnStar or the BMW app).

• Jibo, vacuum the floor downstairs (linked to my Roomba).

• Cortana, make sure my heater is on at home for my arrival.

The next phase, within the next five to ten years, would be an agent that can call and make an appointment with your hairdresser, book your car in for a service and so on. You might even start to personify your agent. Tasks like the following will be common:

• <Lucy> book me a flight next Wednesday afternoon to Florida in first class. Pay using the corporate account.

• <Bob> call my hairdresser and see if they can fit me in on Friday.

• <iThing> can you find out if there are any good matinee shows available in the West End this Saturday?

• <Alfred> find me a Mexican restaurant near the theatre and book me a table for three.

This next level of agency requires the ability for negotiation and interaction with either other agents or with humans. Thus, you need some basic neural networks or learning algorithms that can work to determine the correct response for these types of interactions. These learning algorithms will be shared and publicly available so that collectively these machine intelligences get better at anticipating and reacting appropriately to various response states.

In this level of agency, there is also the ability for your agent avatar to learn your preferences. In the examples above, for instance, <Lucy> would know you prefer a forward window or an aisle seat, <Bob> would know that you need to allow 45 minutes plus waiting time at the hairdresser’s and <iThing> would know you don’t like musicals. As such interactions become more common, we’ll build service layers that allow these agents to negotiate in real time without any human involvement. In other words, computer agents talking to other computer agents or machine-to-machine dedicated interactions.

At this stage, some of you may be thinking about privacy and how to ensure that your agent wouldn’t divulge information without your permission. Keep in mind that the volume of these interactions will quickly mean that it will become impossible for humans to operate as effective intermediaries for very long. There will simply be too much data and too many interactions. Humans will just slow things down and degrade the experience so they’ll be rapidly removed from the role of agents. Sure, you’ll still have your elite concierge service that will enable you to speak to a human, but guess what? Those humans will use agents to do the heavy lifting and repetitive tasks. So, in the end, everyone will be using agents. We’ll even have our agent listening in on our meetings and conversations so it can respond in real time as required.

Imagine sitting in a business meeting or participating in a conference call and agreeing to meet your client or boss in another city next Wednesday afternoon. Then seeing that your agent and theirs have already communicated, put a meeting on the calendar and your agent has already booked you a flight out Tuesday night so that you are there in plenty of time.

None of the above requires full artificial intelligence. A digital personal assistant or agent avatar that could carry out all of those tasks might appear to be quite intelligent, but there is a defined set of experiences it might be able to handle, just like the librarian portrayed in Neal Stephenson’s classic novel Snow Crash (1992). At some point, the capability of these agents will become so good that it will cease being Siri-like (where we laugh at her canned responses) to something we rely upon every day and solves quite complex problems. It simply doesn’t matter that it isn’t full AI.

This capability is most likely to sit on top of multiple operating systems, rather than being dedicated to a specific device. For example, when you are in your self-driving car and you give <Lucy> instructions, is the car using your iPhone 12 embedded agent or is your agent present in your car and home as well as in your smartphone/device? It’s highly likely that this will be a distributed capability and will be tied into the cloud, rather than just an app or service layer in a specific single device. The capability of these algorithms to learn across a wide range of inputs will be the core success factor in anticipating your needs and applying them to context. These algorithms can also learn in different ways depending on the particular device. For example, a smart car may learn your preference for driving routes or preference for the types of restaurants you frequent, perhaps better than your smartphone. Your smart watch with its sensor array might learn which music is optimal for your workout based on how that music changes your physical response to your exercise regimen, or it might learn what time of the day is best for you to have a coffee so as to maximise your alertness.

You’ll recall in chapter 3 our proposition that user interfaces have got increasingly powerful and more capable, but also less complex to operate. At the same time, the platforms that carry those user interfaces are now becoming distributed so that experiences are not limited to one screen. For example, Facebook has a fairly consistent experience across devices, from your smartphone and tablet through to your PC, and Twitter is integrated into your phone as an app, within websites you use and as a stream of notifications. Banking is already spread across an ATM device, your browser for Internet banking, a mobile app for day-to-day banking or monitoring your financial health, Venmo, PayPal or Dwolla for sending money to a friend instantly and your near field communication (NFC)-equipped iPhone with Apple Pay or Android phone with Android Pay for paying at a store.

For your AI agent, however, this will be even more pervasive. So an interesting question to pursue is like Samantha in Her, could you develop a relationship with your agent avatar, your personal AI?

The first appearance of artificial intelligence in popular literature was through a series of articles and subsequent novel published by Samuel Butler in the late 1800s. Erewhon,2 published in 1897, contained three chapters grouped into a story entitled “The Book of the Machines”. In these chapters, Butler postulated that machines might develop consciousness through a sort of Darwinian selection process.

There is no security against the ultimate development of mechanical consciousness, in the fact of machines possessing little consciousness now. A jellyfish has not much consciousness. Reflect upon the extraordinary advance which machines have made during the last few hundred years, and note how slowly the animal and vegetable kingdoms are advancing. The more highly organized machines are creatures not so much of yesterday, as of the last five minutes, so to speak, in comparison with past time.

Samuel Butler on machine consciousness in Erewhon

There are various repetitive themes in science fiction when it comes to AI. There is the concept of AI dominance, human dominance and control over AI, plus the emerging sentience of AIs along with the ethical struggles it results in. There are also AIs like the Librarian in Stephenson’s Snow Crash that, for whatever reason, have been prevented from reaching sentience.

The thing is though, if you are going to talk to an AI, you are going to bestow upon it certain human characteristics. Which is why the representation of AIs has also been a consistent theme in literature, cinema and on TV.

The first avatar, or avatar-like character, to hit the mainstream was Max Headroom. This fictional AI first appeared on British television in 1985 in a cyberpunk TV movie entitled 20 Minutes into the Future. Channel 4 then gave Max his own music-video show, The Max Headroom Show, which led to a brief stint doing advertisements for Coca-Cola’s “New Coke” formula. Though he was billed as “The world’s first computer-generated TV host”, technically Max Headroom wasn’t an avatar or computer-generated at all. Portrayed by actor Matt Frewer, the computer-generated appearance of Max Headroom was achieved with prosthetic make-up and hand-drawn backgrounds as the technology of the time was not sufficiently advanced to achieve the desired effect. Preparing the look for filming involved 4.5 hours of make-up preparation. Frewer described the preparation as “gruelling” and “not fun”, likening it to “being on the inside of a giant tennis ball”.

The classic look for the character was a shiny dark or white suit (actually made out of fibreglass) often paired with Ray-Ban Wayfarer sunglasses. Only his head and shoulders were depicted, usually against a “computer-generated” backdrop of a slowly rotating wire-frame cube interior, which was also initially generated using traditional cel animation, though actual computer graphics were later employed for the backdrop. Another trademark of Max was his speech; his voice would seemingly pitch up or down randomly, or occasionally get stuck in a loop, achieved with a pitch-shifter harmoniser.

Figure 7.2: Max Headroom, the first computer-generated TV host ... or so we thought (Credit: The Max Headroom Show, UK’s Channel 4)

It was only a few years before Max Headroom that computer avatars made their appearance in popular literature. The word avatar is actually from Hinduism and stands for the “descent” of a deity in a terrestrial form. In Norman Spinrad’s novel Songs from the Stars (1980), the term “avatar” was used to describe a computer-generated virtual experience, but it was Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash that cemented the use of the term in respect to computing. In Stephenson’s novel, the main character, Hiro Protagonist, discovers a pseudo-narcotic called Snow Crash, a computer virus that infects avatars in a virtual world known as the Metaverse, but in doing so carries over its effects to the human operators who are plugged into the Metaverse through VR goggles that project images onto the users’ retinas via lasers. Interestingly, Stephenson also described an entire industry built around the business of avatars and the Metaverse, including designers who can fashion a body, clothes and even facial expressions for your virtual persona.

Today, the term “avatar” describes any virtual representation of a user in the digital realm. From Steve and his buddies in Minecraft to characters in Halo, the Guardians in Destiny and avatars in virtual worlds like Second Life. However, the development in computer animation to depict virtual characters in parallel can also be seen as contributing to the possible futures of interaction.

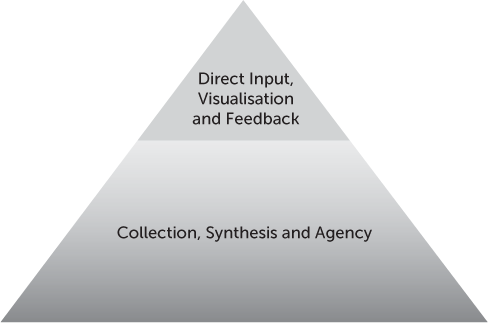

Figure 7.3: Aki Ross, a computer-generated human analog actor in Final Fantasy (Credit: Square Pictures)

From Woody in Toy Story through to James Cameron’s Avatar, the development of computer character animation has evolved into a multi-billion dollar segment of the software industry. The first attempt to depict a photorealistic actor on the big screen was in the 2001 movie Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within. The groundbreaking graphics made some moviegoers uncomfortable, and the film flopped, losing Columbia Pictures US$50 million. For some, the faces were just too human, too close to real life.

“So when you see the curvaceous Dr. Aki Ross (voiced by Ming-Na) trying to save our decimated planet from invading phantoms, you’re seeing the handiwork of a computer, not of Mother Nature. Ever since Sony Pictures previewed Final Fantasy, online critics have been predicting doom. But the film exerts a hold… At first it’s fun to watch … But then you notice a coldness in the eyes, a mechanical quality in the movements.”

Peter Travers, Final Fantasy, Rolling Stone, 6th July 2001

As discussed in chapter 4, the roboticist Masahiro Mori postulated this problem in an obscure journal called Energy in 1970, calling the effect of watching human-like robots Bukimi no Tani Genshō (不気味の谷現象), or what has been translated as the “uncanny valley”.

So it would appear to be a choice between either super realism or some form of representation that is human-like, but clearly distinguishable from human. Enter Hatsune Miku, the Japanese anime, Vocaloid pop star.

“She’s rather more like a goddess: She has human parts, but she transcends human limitations. She’s the great posthuman pop star.”

Hatsune Miku fan site

Miku had her start as a piece of software designed as a voice synthesiser by the Japanese company Crypton Future Media. In 2007, Crypton’s CEO, Hiroyuki Itoh, was looking for a way to market a virtual voice program he’d developed using Yamaha’s Vocaloid 2 technology. What he felt the software needed was an aidoru, or “idol”. He engaged Kei, a Japanese illustrator of graphic novels, to come up with something. Kei came back with a rendering of a 16-year-old girl who was 5 foot 2 inches and weighed 92 pounds. She had long, thin legs, coquettish bug-eyes, pigtailed blue locks that reached almost to the ground and a computer module on her forearm. Her first name, Miku, meant “future”; her surname, Hatsune, “first sound”.

Figure 7.4: Hatsune Miku, the Japanese Vocaloid, avatar, anime pop star worth billions (Credit: Crypton Future Media)

• She has over 100,000 released songs, 1.5 million uploaded YouTube videos and more than 1 million pieces of fan art.

• She has her own Dance craze called the MikuMikuDance, MMD.

• Nomura Research Institute has estimated that since her release in 2007 up until March 2012, she had already generated more than ¥10 trillion (approx. US$130 billion) in revenue.

• She has more endorsements than Tiger Woods and Michael Jordan combined.

• She has over 2.5 million fans on Facebook.

• She has performed more than 30 sold-out concerts worldwide, with performances in Los Angeles, New York, Taipei, Hong Kong, Singapore, Tokyo, Vancouver, Washington and, more recently, in the United States with Lady Gaga.

Miku today has millions of adoring fans all over the world, both online and in the real world. So how has a piece of voice synthesis software become such a huge hit as an avatar or Vocaloid pop star?

For digital natives who have grown up with technology in every aspect of their lives, seeing an avatar perform at a concert is no different experientially to seeing a human performer. For future generations, growing up with an AI or agent in their lives will seem like the most natural thing ever. Of course, there will be a transition from today’s world where such things are novelties, to where they are just a natural part of life. For those of you concerned about privacy, the uncanny valley or how you’ll never have an AI book a restaurant for you, think about it. In 20 years’ time, all of this will be the norm.

Miku has taught us that you don’t need to be human to be a pop star. It is the first time in history that a computer construct has reached this level of real-world popularity. Sure, there have been cartoon characters, fictional characters and comic book superheroes that weren’t real that have been popularised. However, this is the first time an avatar that is absolutely virtual (and not a human analog) has crossed into the real world so completely to compete side by side with humans.

Whether in the form of an avatar or a photorealistic representation of a human being, having a day-to-day working relationship with a computer agent or AI is not even a slight stretch of the imagination. In all likelihood, we won’t need much visual representation of our agent. As in the movie Her and today’s implementation of voice recognition in smartphones and vehicles, the use of agents initially will be via voice. Research so far does not indicate that we have an “uncanny valley” issue with voice interactions, only in physical robotics. The reality is that agents will be rarely personified in a robot. For most of us in the future, we’ll live our lives with an agent that is entirely virtual, and never physical. But we will personify it.

When human fans start adoring and mimicking a virtual pop star, then you can’t argue about acceptance. Miku has taught us that we can adore or, yes, even fall in love with a virtual computer-generated character. For many of us today, this seems difficult to believe but, in 20 years’ time, will it really be that unusual or strange?

Think about it. These agents will be designed to cater for a large part of our daily needs but will be heavily personalised around our individual likes and dislikes, our patterns of behaviour, our biases and reactions. Over time, these agents will get better and better at determining our needs and tailoring responses to us personally. When it comes to human relationships, we often need to change our approach or compromise our own beliefs and feelings to have an effective relationship. In fact, it is very difficult to have a relationship without some form of compromise. When it comes to AI or agency relationships though, you may not have to compromise your behaviour, beliefs or responses at all. In that way, I think it is not hard to see why some might come to feel closer to their agent than other humans.

While some such as Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking raise the spectre of robot overlord AIs that will take over the world with their hyperintelligence, we should also raise the spectre of AIs and avatars that we could very well fall in love with—that capture not only our minds, but also our hearts. This is something we’re only just beginning to explore culturally, but it is a distinct possibility.

For the last 50 to 100 years, we’ve developed service businesses that require a high degree of technical competency and knowledge such as medicine, consulting, financial services and advisory, software, etc. For the 1 per cent, the ultimate expression of wealth might well be having a full-time dedicated concierge or personal assistant that organises your appointments, travel and other activities. The ultimate expression of banking is to have a private banker, your personal one-to-one adviser for all things investment and banking. Having a dedicated nanny and tutors for your children, and having your own personal trainer or dietary/nutritional adviser, rank up there, too.

In each previous age, the core technologies have mainly disrupted infrastructure and processes. In the Augmented Age, however, it is experiences and advice that are being disrupted and scaled today, not processes and distribution.

Age |

Core Technology |

Core Disruption |

Machine or Industrial Age |

Steam Engine Combustion Engine Electricity |

All about Mass + Infrastructure Individual trades to produce goods in favour of factory processes |

Atomic, Jet or Space Age (Tronics) |

Jet Aircraft and Spacecraft Atomic and Solar Energy Telephone |

All about Speed Slow, inefficient production processes and generation Transport and communication systems |

Digital or Information Age |

Computers Internet |

All about the Data Manual Record Keeping Physical Distribution and Products |

Augmented or Intelligence Age |

Artificial Intelligence, Smart Infrastructure, Distributed UX and embedded computing |

All about the Experience Experience and Advice |

Experiences that will be most easily disrupted over the next 30 years are service experiences. Experiences where humans and our inefficiencies, inaccuracies and idiosyncrasies are replaced by intelligence, of the machine kind. Experiences designed from the ground up that fit into our lives in a much more seamless and intelligent way than those human advisers we’ve needed up until now.

Imagine having a dedicated concierge, a personal trainer, a tutor for your children and such, not as a dedicated human resource, but built into technology around us. The fact is that human advisers are going to have significant disadvantages competing with their so-called robo-adviser challengers. Here are the most significant disadvantages:

The example used earlier in chapter 3 is that of IBM Watson either competing against humans in the game show Jeopardy! or providing advice to doctors and nurses in the field of cancer research and treatment. Watson has been provided with millions of documents including medical journals, case studies, dictionaries, encyclopedias, literary works, newswire articles and other databases. Watson is composed of 90 IBM Power 750 servers, each of which uses a 3.5 GHz POWER7 8-core processor, with four threads per core. In all, the Watson system has almost 3,000 POWER7 processor threads and 16 terabytes of RAM.

This means that Watson can process the equivalent of more than 10 million books per second, much like having a photographic memory that can recall anything from those books and sources instantly. Rumour has it that Watson finished med school in just two years. When the cancer research fellows at MD Anderson’s Leukemia Cancer Treatment Center were asked to summarise patients’ records for the senior faculty in the mornings, Watson always had the best answers.

“I was surprised,” said Vitale, a 31-year-old who received her medical degree in Italy. “Even if you work all night, it would be impossible to be able to put this much information together like that.”

“IBM’s Watson computer turns its artificial intelligence to cancer research,” Herald Tribune Health, 14th July 2015

Rob Merkel, who leads IBM Watson Health, said the company estimates that a single person will generate 1 million gigabytes of health-related data throughout a lifetime. That’s as much data as in 300 million books. Multiply that by the billions of people on the planet and it is clear that no human will ever be able to analyse that data efficiently, and definitely not in real time.

We are now well beyond the realms of a human adviser being able to have his “finger on the pulse” of the right information to give you accurate advice. More importantly, human advisers in the field of financial services, for example, have been notoriously bad at synthesizing individual investment styles, risk appetite and other personal parameters and introducing those into investment advice. This is where AIs will have a huge advantage—they’ll be able to synthesize all of this type of data into “advice”.

Whether it is the latest industry data, the latest research or just information about the last stocks or symptoms you looked up on the web, machines will have more data, more immediate access and the ability to have instant recall at anytime day or night. Simply put, for the last 200 years, advisers have worked on the principle of information asymmetry, where they have had better information than their clients. Today, we are at the point where machine intelligence has information asymmetry over advisers, and that’s only going to get more acute and more asymmetrical as time goes on. The only possible hope for human advisers is that they co-opt machine intelligence into their process.

At best, an adviser is “just a phone call away”, but at worst is only available by appointment, dependent on availability. Advice, however, no longer needs to be hinged on access to the adviser as a precursor to whether you can get access to certain information.

The first concept we need to challenge is simply that you need to “go to an adviser” to get advice. Advisers have used their information asymmetry previously to insist that unless you come to them, you won’t get the right advice, or they have used asymmetry to price in a premium into the service or product. So if you wanted the right advice, not only did you have to jump through their hoops, go to their branch, office or clinic, but you also had to pay a premium for the best advice, maybe waiting days or even weeks to get to see the best advisers. Your ability to pay, or your access to a specific network, no longer needs to be a factor as to whether you can get good advice on things like your money, health care, fitness, etc.

Whether it is an Apple Watch or a Samsung Simband tracking your heart health in real time and asking an AI to analyse that for anomalies, your electric vehicle telling you the optimal time of the day to recharge or to travel (even automatically scheduling it), your bank account telling you if you are spending too much money, your smart contact lenses telling you to eat a piece of fresh fruit to improve your blood sugar levels or your smartphone telling you to reduce your caffeine intake for the next three hours, advice is going to increasingly become embedded in our lives through technological feedback loops.

Let me try putting it another way.

What is better? A personal network of smartphone, smartwatch, smart clothing or ingested sensors that monitors your heart health over time, finding that your heart health is deteriorating due to increasing incidence of cardiac arrhythmia OR waiting until you have chest pains to see a doctor and hoping that when he hooks up the ECG in the clinic it shows the sporadic arrhythmia that is causing the issue?

What is better? A financial adviser you meet once a year who gives you guidance on your portfolio and investment strategy, and basically tries to pitch you the hot investment fund of the month OR a bank account that is smart enough to monitor your daily spending as you tap your phone to pay and then coach you on how to change your behaviour so you save more money, as well as looking out for the best deals on the things you really want to splurge on, and a robo-adviser that is constantly optimising your investment portfolio to maximise your returns, with lower tolerances and better information than the best financial adviser in the world has access to?

Whether it is advice on how to optimise your day’s activities from your bathroom mirror, an interactive chef that helps you cook your next meal or a travel advisory algorithm that optimises which flights you should book to increase your chance of an upgrade, there will increasingly be advice embedded into the world around us where it matters the most. There will be very few instances where a human who can give you advice at a future time with inferior data will compete with technologically embedded, contextual advice in real time.

Machine learning has been limited in the past by pattern recognition, natural speech and other deficiencies, but machines are beginning to catch up quickly. The advantage that machines connected to the Internet of Things and sensors will have is that they will be able to learn about your behaviour much more efficiently than service organisations today.

How do service organisations today learn about your preferences? There are really only four ways:

• demographic-based assumptions

• surveys, marketing databases and user panels

• data you’ve previously entered into the system or on a form

• preferences you might input into an app, online portal or other configurator

All of these are imprecise ways of measuring your preferences and behaviour, and at a very minimum depend on both your diligence and honesty in answering, and the effectiveness of the organisation in collecting and synthesizing that data.

In the banking arena, there is a classic example of this type of data conflict. If you survey customers about whether or not they “prefer” to do banking at a bank branch, most customers will say yes, particularly for an activity like account opening or applying for a mortgage. However, if you actually monitor the behaviour of customers, you’ll find that more than half of new customers sign up online today, and in most developed economies we’re approaching a third of customers who no longer visit the branch. Asking people questions in a survey is just not as accurate as observing their behaviour in the real world.

Observation field studies are a study method that works great in actually seeing someone in an environment where they are using a physical space, or a device, as long as you can get enough clarity on what they are doing, and have their permission to use that data. It is, however, very labour intensive and expensive. You just can’t do it frequently.

Sensors have the ability to change all of that. The sensors we are embedding in the world around us such as cameras, accelerometers, GPS geolocation tracking and so forth in our smartphones, heart rate and biometric sensors in our watches, plus WiFi hotspots, app plug-ins, web cookies and so forth are collecting data about our behaviour constantly. This data could even assess our emotional state, but most certainly will have a much more comprehensive view of our behaviour over time.

Ultimately, the future of service interaction is clear. Massive data processing capability is at the core of what will make AIs better advisers than humans, even if humans have access to the same data. Synthesis of data is where humans can no longer compete. It is where services provided by AI agents in the future will differentiate. Get used to telling people your smartphone AI knows you better than you know yourself.

If you are an adviser of some sort today, this is undoubtedly daunting, just as it must have been for the textile artisans of the early 1800s when steam machines were emerging. Nevertheless, it doesn’t change the likely future heading our way.

____________

1 Just kidding! I haven’t registered the trademark—yet!

2 Available at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1906.