As early as 1927 Eugene O’Neill left evidence that he wanted to write a play like Long Day’s Journey Into Night in notes for one or more plays about his mother, father, brother, and himself to be called “The Sea-Mother’s Son.” O’Neill’s turn to intensely self-reflective work is a crucial moment in his career, indeed in theater, but it came as a consequence of a whole life story. At age thirty-eight he was acknowledged as America’s foremost playwright, the first to achieve worldwide recognition. He had been writing plays for fourteen years and producing full-length plays since 1920. He was ranging widely and probing deeply in quest of an approach to drama that would put him among the defining figures of modern art.1 He wished to leave far behind what he considered the triviality and commercialism of Broadway, which he called the “Show Shop” (a place to cobble together goods for quick sale).2 Instead, he sought to follow the model of the Titan artist, creating for himself (and incidentally the audience) works of magnitude, deep meaning, power, and truth—all the terms associated with greatness in art since Aeschylus, Beethoven, Dostoyevsky, Strindberg, and many other immortals he admired.3 A shop is also necessary for that sort of work—plays are built as well as envisioned—and O’Neill had assembled the proper tools and learned the skills. He had also paid attention to the question of what an audience would accept, but art—not profit—was his motive. As early as 1914, at age twenty-five, he declared, “I want to be an artist or nothing,” and that remained his resolve even after the royalties began flooding in.4 His vision was bold, his attitude uncompromising, and his ambition nothing less than epochal: to remake tragedy for the twentieth century. In a letter of 1928 he expressed this goal, saying that he was trying to

dig at the roots of the sickness of Today as I feel it—the death of the old God and the failure of Science and Materialism to give any satisfying new one for the surviving primitive religious instinct to find a meaning for life in, and to comfort its fears of death with. It seems to me anyone trying to do big work nowadays must have this big subject behind all the little subjects of his plays or novels, or he is simply scribbling around on the surface of things and has no more real status than a parlor entertainer.5

Just as he began to see the possibility of reaching his aspiration, O’Neill realized that his chief obstacle would be himself. A worsening tremor in his hands made it clear that his future as a writer had a limit, and even as he turned forty he understood his own mortality. One marriage was coming to an end, and another was taking shape. It seemed the proper time to take account of his life, and he found an image of himself as the son of a “sea-mother,” an artist born out of early experience with the maternal and the nautical, mythically combined into one. Earlier in the 1920s, in three short years, O’Neill had lost all his immediate family members—first father, then mother, then brother—and shortly afterward had recognized that his drinking was setting him on a death course. He put alcohol aside in 1926 and rededicated himself to writing with confidence that he could, with his talent and determination, create a body of work, a legacy in drama, that would defy oblivion, if only he could rise above the fear of his own end.

A play to which O’Neill devoted much attention in the mid-1920s was Lazarus Laughed, about the biblical Lazarus whom Jesus brought back from the dead. O’Neill’s Lazarus returns filled with laughter to announce, “There is no death!” The play gives a stunningly hopeful vision of the eternal, but the time-bound O’Neill discovered that the pragmatic world of 1920s Broadway wanted nothing to do with the play, in part because it required a cast of hundreds and more than a thousand masks and costumes. With this play, O’Neill overreached, but his desire to say something for all time and to celebrate his rebirth would come to fruition in other forms. A lesson he took from the experience was not to be distracted by the stunted vision, narrow concerns, and petty gratifications of Broadway. He instead wrote plays of epic scope, of three hours, four hours, plays of novelistic complexity, plays of world myth and metaphysics and the evils of materialism. To a remarkable degree, in a rather carefree era, the audience responded to his demanding art, though perhaps the reason had more to do with his willingness to reveal onstage the shocking limits of private experience, especially within family relations, and the human susceptibility to scandalous disaster. Strange Interlude (1928) took the audience into the inner recesses of the mind of an adulterous woman and the men clustered around her. The performance, much of it inner monologue, took four and a half hours. Nevertheless, it was the hottest ticket of the Broadway season.

By 1928, O’Neill had received three Pulitzer Prizes for his plays, and in 1936 he became the first (and to this day only) American playwright to receive the Nobel Prize in literature. But even those markers hardly gauge the impact of O’Neill in revolutionizing American drama. That seriousness might become a selling point for a play, that an evening at the theater might take an audience on a journey as profound as an epic poem, that an American play might be read and reread in an edition worthy of a first-rate novel, that books and essays might be written by first-rate intellectuals about an author of playscripts—all this can be largely attributed to O’Neill. Even then, as Tony Kushner has remarked, O’Neill was the rare case of a writer whose best work came after winning the Nobel Prize, and Long Day’s Journey, written in 1939–1940 but not published or produced until 1956, has been considered by many the towering achievement of them all.6 So, it awaited another generation to take the full measure of the man’s work.

The more widely recognized O’Neill became, the more he withdrew into privacy, even isolation. The circumstances of his childhood and youth had not been happy, with many conflicts and agonizing episodes. But the loss of his parents and brother and the awareness of his own death wish led him to recognize himself as a man caught in tragic circumstances, not unlike a character in one of his own plays, such as the self-obliterating Edmund, who calls himself “a stranger who never feels at home, who does not really want and is not really wanted, who can never belong, who must always be a little in love with death!” (157).7 O’Neill’s height as an artist depended on the depths into which he was willing to go, but those depths could doom his ascent. The collateral facts of being, already, by the early 1920s, prosperous, admired, and settled in a decent marriage, blessed with children, and living in a series of beautiful homes did not stave off the overwhelming shame, guilt, self-hatred, and fear of death to which he was subject. Doris Alexander argues that O’Neill again became suicidal after the death of his brother, Jamie, and that he was “painfully alive to his tragic heritage from Jamie. He had actually experienced in himself Jamie’s tragic rush toward death and the pangs of his corroded genius.”8 These feelings made O’Neill a difficult man to know and love at times, but they also constituted the raw material of his art. His plays became the machines to transform these disturbed emotions into works of permanent importance.

The idea of directly using some aspect of his own life story as the material of a play goes back further, at least as far as 1919, when he wrote the recently retrieved Exorcism.9 This one-act play dramatizes the moment in 1912 when he attempted suicide by overdose in a rented room above a derelict bar in lower Manhattan. Other residents broke down the door to save him, and O’Neill’s father came to the rescue by luring him to the family’s summer house in New London and getting him a job as a reporter for the local newspaper. In Exorcism, the suicidal character is named Ned Malloy, and the comparison with Edmund Tyrone is hard to miss. Ned’s reason for taking such a drastic measure as attempting suicide is his shame for having impulsively made a mess by marrying a young woman and then abandoning her. Deepening the shame, he had arranged to be witnessed with a prostitute in order to establish legal grounds for a decree of divorce. All this in fact took place in O’Neill’s life early in 1912, the year in which Long Day’s Journey is set. He wrote Exorcism a year and a half after his remarriage to the writer Agnes Boulton when she was pregnant with his second child as well as hers, counting one from a previous relationship. He and his new wife had been raised Catholic, and both had, on some level, corrupted the sanctity of marriage. Agnes seemed troubled only slightly by this reality, but O’Neill took it to heart, probably because he could not avoid confusing the terms of his relationships with wife, mother, and son with his unresolved feelings about his parents and brother, the material that would be developed into Long Day’s Journey.

O’Neill gave Exorcism to the Provincetown Players, the company that did the most to launch his career as a playwright, for production in spring 1920. By sad coincidence, his father was diagnosed with terminal cancer during rehearsal. No record tells us whether James O’Neill or even Eugene O’Neill saw the production, which lasted just two weeks, but some feeling of remorse or shame led the writer to wish to eradicate his play, which in an oddly joking way mocks his own youthful despair and his father’s compassion on that occasion. O’Neill called for the return and destruction of all copies of the script, but his own typescript resurfaced in 2011. The description of Exorcism in the Provincetown Players’ playbill, “A Play of Anti-Climax,” ironically applies to how this play jumps the gun on the mature self-representation he would venture in Long Day’s Journey.

Travis Bogard, in his important critical study of all of O’Neill’s plays, Contour in Time, makes the case that most of O’Neill’s plays can be read as more or less disguised efforts at autobiography or at least self-reflection through interpretable codes. Bogard’s point of view is one that defies a precept of mid-twentieth-century literary criticism—namely, that a work of literary art should be read “in itself,” solely as a work of art, without external justification or rationale. O’Neill critics, especially when they consider Long Day’s Journey, face the question whether to read the work in terms of the life, just as biographers face the question whether to read the life in terms of the work. Many have addressed these questions with subtle arguments, but Bogard prefers to look directly at O’Neill’s choice to explore how drama might do something like the work of autobiography.10 Indeed, we can understand the autobiographical turn as yet another gesture in O’Neill’s career toward challenging the conventions of the theater. In 1919, his effort was awkward and embarrassing, but he did not reject the premise that self-dramatization was a worthy experiment, so that, for example, in his 1925 play All God’s Chillun Got Wings he gave the two main characters the names Jim and Ella, exactly the names of his mother and father.

Then, in 1927, as his marriage to Agnes was fracturing, he wrote in his Work Diary: “Worked doping out preliminary outline for ‘The Sea-Mother’s Son’—series of plays based on autobiographical material.”11 In 1928, he referred to this idea as the “grand opus of my life,” adding that it had “been much in my dreams of late.” A few months later, he sketched a play with that title, which would depict a man of forty (O’Neill turned forty that year) in a hospital room at the point of death. He finds in himself a strong death wish but also the will to fight against it, “and he begins to examine his old life from the beginnings of his childhood.”12 He is “participant and spectator— interpreter” in his troubled life story. At the end, by “accepting all the suffering he has been through, he is able to say yes to his life, to come back to the plane of wife and children, to conquer his death wish, give up the comfort of the return to Mother Death.”13 When he wrote these words, far from returning to his wife and children, he was onboard a ship to China with the actress Carlotta Monterey. This woman, who would become his third wife, was not a figure of death but, to him, maternal, one in whom he felt he could be reborn. In 1932 he inscribed a typescript of Mourning Becomes Electra to her as “mother and wife and mistress and friend!!— / And collaborator! Collaborator, I love you!”14 Mother—or some abstraction with that name—was on his mind as he sailed in search of a new home, perhaps already anticipating the words he would later give to Edmund: “I was set free! I dissolved in the sea, became white sails and flying spray, became beauty and rhythm, became moonlight and the ship and the high dim-starred sky! I belonged, without past or future, within peace and unity and a wild joy, within something greater than my own life, or the life of Man, to Life itself !” (156).

He tinkered with this “sea-mother” idea for a play or series of plays several times over the next few years, at one point describing it as “a combination autobiographical novel in play form for publication in book, not production on stage,” but his attention turned to other grandiose projects in the 1930s.15 Finally, in June 1939, at a point when he was facing another series of crises—chronic health problems, alienation from his children, tension in his marriage, and news of the approach of World War II—he set aside the enormous and never-finished series of plays on which he had been working for several years and turned to two plays he says he had planned years earlier. The first, which he wrote later that year, was The Iceman Cometh, a four-hour exploration of tragic self-delusion set in the same derelict bar as Exorcism. The second was what he called the “N[ew]. L[ondon]. family one,” which seems to have been a portion of “The Sea-Mother’s Son.”16 Within a month, he had outlined a play he was calling “Long Day’s Journey.” On a rainy February 22, 1940, he got the idea for a “better title”: Long Day’s Journey Into Night.17

Two other documents written by O’Neill attest to his effort to interpret his life story, though both of these might have been generated as part of the psychoanalysis in which he briefly engaged in the 1920s. They help us understand why O’Neill’s play, aside from its power as drama, has been studied by psychologists for what it reveals about self-analysis, about family dynamics and patterns of addiction and codependency, and about such psychoanalytic concepts as narcissism and the “dead mother.”18 Freud’s emphasis on a patient delving into earliest memories, especially the child’s relationship with its parents, had become widely accepted in American psychiatric practice at the time O’Neill sought treatment for his drinking in 1925–1926.19 O’Neill might well have written these notes for his sessions with Dr. Gilbert V. T. Hamilton or some other professional, but the terms used correspond so well with the story developed in Long Day’s Journey that they might have also been used as early notes on “The Sea-Mother’s Son.” One is an unheaded page that reads, in part:

M[other]—Lonely life—spoiled before marriage (husband friend of father’s—father his great admirer—drinking companions)—fashionable convent girl—religious & naïve—talent for music—physical beauty—ostracism after marriage due to husband’s profession—lonely life after marriage—no contact with husband’s friends—husband man’s man—heavy drinker— out with men until small hours every night—slept late—little time with her—stingy about money due to his childhood experience with grinding poverty after his father deserted family to return to Ireland to spend last days. . . .

E[ugene (or Edmund?)]. born—with difficulty—M sick but nurses child—starts treatment with Doc. which eventually winds up in start of nervousness, drinking & drug-addiction. No signs of these before.20

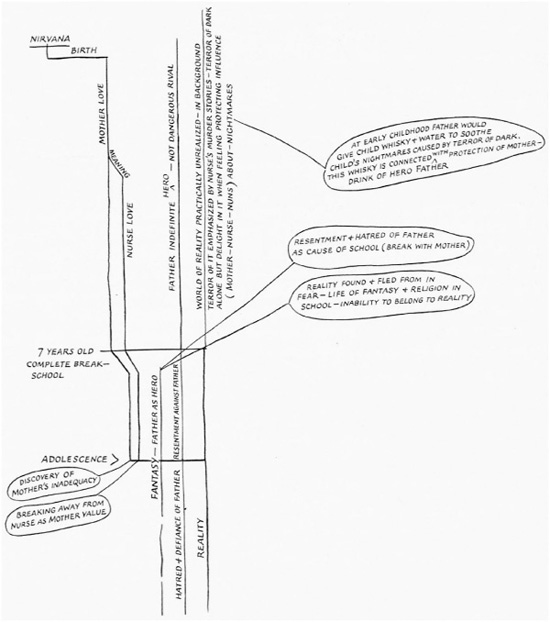

The other is a diagram, a developmental timeline, showing O’Neill’s passage from birth (“Nirvana”) to an adolescent awakening to “reality.” Notes along the line show the points at which he confronted the “inadequacy” of mother and father as a source of love and a heroic model, respectively. He correlates the pathway of discovery with the awakening of his imagination as an escape from fearful reality through fantasy, literature, religion, and alcohol.21

“O’Neill’s Diagram,” as transcribed by Louis Sheaffer, O’Neill’s biographer, from a manuscript in the Eugene O’Neill Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. O’Neill wrote the original in script so small it is nearly impossible to read. The transcript is in the Louis Sheaffer– Eugene O’Neill Collection, Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives, Connecticut College. (Courtesy of the Estate of Louis Sheaffer)

Stephen A. Black has made the case, in his 2000 biography, Eugene O’Neill: Beyond Mourning and Tragedy, that O’Neill abandoned psycho therapy in the 1920s only to pursue his own ultimately successful self-analysis in his writing, a process he brought to a culmination in Long Day’s Journey. That he generated two such deeply self-analytical documents as these from his brief experience of psychotherapy testifies either that the work advanced to an extraordinary degree or that he was supplying his own strengths as a creator and interpreter of character to himself. Ultimately, in order to build a better play, the art he employed in writing Long Day’s Journey required him to manipulate the facts. So, for example, as Black points out, the autobiographical notes say that O’Neill’s mother became a drinker as well as a drug addict after his birth. In the play, it works better to have the men use alcohol as an escape from the present, while Mary turns to morphine. O’Neill’s mother could hardly have been encouraged by her father to marry James, since her father had been dead for three years when they wed, and most likely no elaborate wedding dress would have been stored in the attic because probably no such dress had been worn.22 These and other details have been studied closely in Doris Alexander’s important 2005 study, Eugene O’Neill’s Last Plays: Separating Art fr om Autobiography.23

The story of O’Neill’s family, as he limns it in the play, corresponds in most details with facts that can be established in other ways; yet there was no one day in 1912 when all these events occurred. The long August day of diagnosis and relapse, reminiscence and confession, was a lens through which a larger life history could be brought into focus. O’Neill’s father rose from poverty as a promising young actor who then attached himself to a money-making romantic role. The Count of Monte Cristo was “that God-damned play I bought for a song.” His performance as Edmond Dantès defined and delimited his career, as over thirty years he appeared more than four thousand times in the role. Alexandre Dumas’s revenge story, set mainly in the post-Napoleonic years, addressed the fraudulent values and materialism of the era in which James O’Neill grew up. But it is also a story of broken families, especially fathers separated from sons, and there are ironies in the way Dumas’s story, which was itself somewhat autobiographical, lurks in the background of Long Day’s Journey. Around the time when O’Neill’s play is set, August 1912, James O’Neill was playing Dantès in Monte Cristo yet again for the first and only movie he was ever in, a fifty-six-minute version, perhaps the longest movie ever made at that time, which can now be found easily on the Internet. The scenery and acting seem painfully artificial except for one scene, in which James O’Neill, at the age of sixty-six, playing a not-yet-forty Dantès, swims to shore from Long Island Sound, climbs onto a rock, and lifts his drenched arms so that we can imagine him speaking the famous line, “The world is mine!”

The world was no longer James O’Neill’s in 1912; he had just lost a large investment in a failed tour of the play on the vaudeville circuit, and he would lose more from the movie version. It is difficult to calculate exact equivalencies in income, but the $35,000 to $45,000 per season that he recalled earning would equal around $1 million to $2 million today. Much of that money was invested in real estate, so the O’Neills continued to live in comfort in the last decade of their lives despite the financial losses. In 1931, O’Neill recalled his impression of his father’s empty triumph in that role:

I can still see my father, dripping with salt and sawdust, climbing on a stool behind the swinging profile of dashing waves. It was then that the calcium lights in the gallery played on his long beard and tattered clothes, as with arms outstretched he declared that the world was his.

This was a signal for the house to burst into a deafening applause that overwhelmed the noise of the storm manufactured backstage. It was an artificial age, an age ashamed of its own feelings, and the theatre reflected its thoughts. Virtue always triumphed and vice always got its just deserts. It accepted nothing half-way; a man was either a hero or a villain, and a woman was either virtuous or vile.24

The aesthetic of Long Day’s Journey stays as far from such artificiality as possible, but the foghorn reminds us of that same overwhelming sea, and virtue and vice seem to wrestle within each character, so that villainy and innocence stand at odds in a way that might seem, from moment to moment, melodramatic. It’s the art of the actor or sensitive reader that keeps the characters realistic.25 For Eugene O’Neill, the image of his actor father amid such artificial theatricality gave an

James O’Neill in The Count of Monte Cristo, from an 1880s souvenir program. (Louis Sheaffer–Eugene O’Neill Collection, Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives, Connecticut College)

unfortunate perception of his all-too-real father. On the other hand, the image of James Tyrone on a stage is always the creation of some man who is an actor, yet an actor who aims to embody something authentic about James O’Neill, and not by “dripping with salt and sawdust.” The realistic constantly bumps up against the real in this play, but both bear traces of the artificial or fake.

The other gauge of Tyrone’s achievement is in the memory of having performed opposite Edwin Booth (1833–1893), the most es teemed American actor of his era, known for his naturalistic style of acting, especially in roles like Hamlet. By 1912, though, James O’Neill was at the end of his career, which was increasingly vested in the romantic and melodramatic at a time when the larger trends, even in the commercial theater, were toward the realistic. He was saddled with two sons who were given chances to work in the theater, but neither had relished the opportunity. Eugene was less than a year from his suicide attempt and showing signs of consumption (tuberculosis). James, Jr., at thirty-four, had played parts in his father’s company over the years, but he was a chronic alcoholic, deeply embittered and self-hating. They might all have felt that 1912 was a moment when the family had outgrown the theater, which had been its way of life. As young Eugene watched his mother escape into her own artificial reality, he might well have come to a resolve about the dangers of theatricality. In that autobiographical diagram, he writes of his early years that the “world of reality [was] practically unrealized” until “discovery of mother’s inadequacy.”26

James, Sr., was a rapidly rising actor when he met Mary Ellen (Ella) Quinlan in 1872 and again in 1874, and he was near the acme of his career when they married three years later. Jamie was born in 1878. Life on the road with a child was difficult, and more so when a second child was born five years later, in 1883. They named the boy Edmund Burke O’Neill after the eighteenth-century Irish political theorist and advocate for Irish independence, though the Edmond of Monte Cristo may also have come to mind. Newspaper reports confirm the sad facts of the toddler contracting measles in 1885 while in the care of Ella’s mother. Ella received this news when she was with James on tour in Denver and did not arrive back in New York before little Edmund died. In 1919 she told Eugene’s pregnant wife, Agnes: “He might not have died if I hadn’t left him; we had a good nurse, a very good nurse, and James wanted me to go on tour—he can’t seem to manage without me.”27 Eugene was born three years later, on October 16, 1888, in a hotel room on Times Square. The morphine used to treat Ella’s labor pains became an addiction that erupted periodically over the next quarter of a century until she finally overcame it in a Brooklyn convent in 1914.

By the time of Eugene’s birth, the O’Neills had purchased for summer use the first of two houses they occupied in New London, and

Mary Ellen Quinlan, around the time she married James O’Neill in 1877. (Eugene O’Neill Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

no doubt an element of anguish and guilt was also formed into that home, such that the word might have seemed inappropriate, as Mary Tyrone expresses it: “Oh, I’m so sick and tired of pretending this is a home!” (69). They chose New London because Ella’s mother had moved there to be near her sister, but many successful actors of the day established summer homes on the Connecticut shore.

The second of the two New London houses, into which they moved when Eugene was about twelve, still stands and is accessible to those interested in seeing the rooms described (accurately) by O’Neill in his stage directions. Most people find the house, known as Monte Cristo Cottage, with its broad front porch overlooking a double lot on the

Monte Cristo Cottage, New London, in 1937. (Louis Sheaffer–Eugene O’Neill Collection, Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives, Connecticut College)

bank of the Thames River, near where it joins Long Island Sound, to be not what one would expect of a miser. Still, what constitutes a good home cannot be reduced to carpentry and a good view. It was in this house that Eugene discovered his mother’s addiction in 1903, when he was nearly fifteen, at a point when she lacked a supply of the drug and nearly threw herself into the river in agony.28

Eugene and Jamie developed little affection for New London, which they saw as a backwater, but they lived in a beautiful area a long trolley ride from town. O’Neill biographers have tracked down

Eugene O’Neill, at about twelve, on the front porch of Monte Cristo Cottage, with his brother Jamie, about twenty-two, and his father, James, about fifty-six. (Louis Sheaffer–Eugene O’Neill Collection, Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives, Connecticut College)

the New London bars and clubs frequented by the O’Neills, as well as the brothel here called Mamie Burns’.29 In 1932, after his last visit to Monte Cristo Cottage, O’Neill wrote one of the few comedies he ever plotted out and the only one to be produced and published in his lifetime. Ah! Wilderness takes place in “a large small-town in Connecticut,” just down the street, as it were, from Long Day’s Journey. Far from an autobiography, the play is rather a fantasia on the adolescence he might have had in New London, making it clear that his cynical attitude about that environment was mixed with some nostalgia.

James O’Neill did indeed buy a lot of property in the area. Eugene inherited much of it in 1923, at which point he found that the investments were below average for that high-yielding era, though he managed to sell most of the “bum properties” before values plum meted in the Great Depression. One parcel was farmed by a man known as “Dirty” Dolan, who was the model for Shaughnessy, while the millionaire with the ice pond was a composite of two tycoons with estates in the vicinity, one of whom was an heir to Standard Oil money. By strange irony, that estate is now the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center, an institution created to nurture theater artists, especially playwrights.

Though in a sense the first draft of Long Day’s Journey was life, in which a story was inscribed on the subject, the writing of the play needs to be separated out as a constructive act, and an amazing piece of construction it is. O’Neill worked on the play in several distinct periods over about two years. His third wife, Carlotta, described the difficult experience of his writing: “When he started Long Day’s Journey, it was a most strange experience to watch that man being tortured every day by his own writing. He would come out of his study at the end of a day gaunt and sometimes weeping. His eyes would be all red and he looked ten years older than when he went in in the morning.”30 He began on June 25, 1939, taking a little over a week to write a scenario, then, six months later, spent two and a half months drafting the first act (February–April 1940). Illness and an obsession with the dire news of the Nazi occupation of France interrupted the work for about two months (May–June 1940). Over the summer, he wrote the rest of the play, finishing the first draft on September 20. He immediately began work on a revised draft , finishing on his fifty-second birthday, October 16, 1940. In mid-March 1941 he began cutting and revising what he called the first draft, which Carlotta had typed. On March 30 he finished “going over” the final draft, commenting in his diary, “[I] like this play better than any I have ever written—done most with the least—a quiet play!—and a great one, I believe.” Then, two days later, he added “father’s M[onte]. C[risto]. speech.”31 Carlotta typed the final manuscript over the next six weeks, and Gene (as she called him) gave her the original longhand manuscript of the play, with his inscription, on their twelfth wedding anniversary, July 22, 1941.32

As early as 1929, O’Neill wrote to his friend and sometime producer Kenneth Macgowan: “Hereafter I write plays primarily as literature to be read—and the more simply they read, the better they will act, no matter what technique is used.”33 From the time of his first (self-published) book in 1914, O’Neill had always taken care to see that his plays were published in well-designed and readable volumes, in editions signifying that these were works of literature, comparable to editions of Henrik Ibsen, G. B. Shaw, August Strindberg, and other modern masters. But his intention with Long Day’s Journey was that it should be made available, twenty-five years after his death, as a published work only, and these stipulations were accepted in 1945 by Bennett Cerf, the head of Random House. O’Neill reaffirmed his intention in 1951. Carlotta, whom O’Neill designated executor of his estate, insisted that he changed his mind when he was near death, leaving her free to handle the play as she saw fit. Cerf and others who had known O’Neill expressed outrage that she was overriding her husband’s wishes. O’Neill’s close friend and editor Saxe Commins declared: “She’s determined to exhume Gene’s body and give him no peace—even in death.”34 Some have hypothesized that her motive was self-justification, giving evidence that her influence on O’Neill had been to the good, despite stories that had circulated concerning the sometimes violent conflicts she had with him in his later years. Furthermore, she had not been kind to many of O’Neill’s friends over the years, and they took her handling of the release of Long Day’s Journey as an occasion to make public their opposition to her. In reaction to their protests, in 1956, Carlotta revoked Random House’s rights to the play and reassigned them to Yale University Press.

The Yale University library had long been the chosen archive for O’Neill’s papers, and Carlotta was in close communication with the university, transferring materials and eventually literary and production rights to many of O’Neill’s writings, so it seemed a good choice to select the nonprofit university press as publisher, if only because it would show that her aim was not to enrich herself. A letter she wrote on December 18, 1956, to Norman Donaldson, director of Yale University Press, makes clear how she understood her purpose:

I was responsible for O’Neill’s being brought back & appreciated by the American public—who had brushed him aside— none too gently—for the past ten years! God knows what would have happened if Dr. Gierow of the Swedish Royal Theatre had not produced “Long Day’s Journey Into Night”—as Gene so wished. Destiny!

Then you—& your Press—made a beautiful book of it—&it went on & on.35

The book jacket featured a black-and-white photograph of O’Neill standing on the back porch of the château known as Le Plessis, outside Tours, France, where he and Carlotta had lived from 1929 to 1931. Wearing an elegant wool sweater, he poses casually, handsome, unsmiling, not looking at the camera. The photo, taken by Carlotta, has been somewhat obviously retouched to suggest that it is night, as well as to provide a black background for the title. All in all, the image reminds us more of the man with whom Carlotta fell in love than the sickly man who wrote the play a dozen years later or the sickly man who was the model for Edmund Tyrone in 1912. Yet it holds the eye as the title holds the ear as an emblem of high seriousness in art. His vision is into the distance.

The play does not follow the classic form of tragedy, though it is “serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude,” as Aristotle asks, while evoking some combination of “pity and fear.” The web of circumstance in which the characters are all caught seems akin to tragic fate, but it consists of nothing more substantial than “the Past.” No gods have gone crazy, no war or plague or heresy has beset, no Iago or Trigorin or Stanley Kowalski has worked his ill way. The more we learn of the past of the characters, the more ordinary or less singular they seem. A child died of measles; a man did not rise to his own expectations; a brother could not curb the hostility that underlay his love; a poet’s health broke down. Meanwhile, no downfall or reversal is traced, no hero is wounded, and each character comes equally to insight and blindness, anagnorisis and oblivion. But the upshot is that they will bear on through other days, because that is what life is. They are not mythic figures on whom story has been written in bold letters, though they habitually fantasize about themselves as such—as the romantic actor, the blessed virgin, the Frankenstein, the seer beyond the veil of illusion. But when their stories fully unfold, they present individuals who could not bear the not-uncommon difficulties to which life has subjected them—deep-seated fear of poverty, physical addiction to escape physical and emotional pain, gnawing guilt over an accidental death, sadness at being slighted by a parent, diminution of religious faith, disappointment at one’s own weakness or inarticulacy, and so on. The family has experienced these trials in a concentrated form through these sixteen hours, but still, this is not the material on which Sophocles or Shakespeare would stretch a plot.

Michael Hinden argues that O’Neill’s characteristic approach to the tragic should be seen as a synthesis of the Aristotelian and the Nietzschean: “It pictures the hero as a moral agent who ignores life’s underlying realities and who consequently must be held accountable for his own self-destruction.” However, in Long Day’s Journey, O’Neill has avoided structuring his plot around a central hero, so that the moral implication cannot be so easily extracted. Instead, as Hinden points out, “At the end of the play the question of who is at fault has lost most of its meaning.” In its place, O’Neill has provided the occasion for what Hinden calls a “theater of forgiveness,” which he sees as a profound redefinition of tragedy for the twentieth century.36

Long Day’s Journey bears little trace of the well-made play, which was known for intricate plot development meant to bring forward a buried truth, restoring happiness out of confusion and, by coup de théâtre, surprising the audience into a recognition of the author’s perspicacity, thus giving reassurance that the universe in which human drama occurs is ultimately benevolent. The well-made play established a pattern for producing the “feel-good” experience in an audience; the truth, once known, will reward you double with freedom and understanding. O’Neill despised manipulating dramatic action to create that effect, and his understanding of human destiny was far from optimistic. Yet buried truth does come forward in Long Day’s Journey, and the genius of the author, who comes to seem a benevolent figure, capable of understanding, forgiveness, and love for these characters, becomes palpable.37 O’Neill described the admixture of the fortunate and unfortunate in the play’s ending in a letter to George Jean Nathan, written after he had draft ed only the scenario and first act: “At the final curtain, there they still are, trapped within each other by the past, each guilty and at the same time innocent, scorning, loving, pitying each other, understanding, and yet not understanding at all, forgiving but still doomed never to be able to forget.”38 The past, a blend of pleasures and pains, reconstructed at full scale, suffuses the present, giving the audience the feeling of having lived through the long journey rather than seeing a story resolved, much less delivered to a happy ending, as in the well-made play.

Still less is the play a melodrama. O’Neill confines his drama to one ordinary setting, using only the passing of day into night as an effect, and his family of characters face no outside foe, no face of modern wickedness. If evil is to be found, it is alongside the good in each character. They all reflect a moral balance, so that no hero versus villain pattern emerges, though moment to moment they oft en polarize. Kurt Eisen, in The Inner Strength of Opposites: O’Neill’s Novelistic Drama and the Melodramatic Imagination, quotes the literary theorist Peter Brooks’s book on melodrama:

The desire to express all seems a fundamental characteristic of the melodramatic mode. Nothing is spared because nothing is left unsaid; the characters stand on stage and utter the unspeakable, give voice to their deepest feelings, dramatize through their heightened and polarized words and gestures the whole lesson of their relationship. They assume primary psychic roles, father, mother, child, and express basic psychic conditions.

In these ways, O’Neill’s play retraces melodramatic patterns, but Eisen then points out that “Long Day’s Journey transforms the melodramatic self-other antithesis into a more complex intersubjectivity in which family is not merely a system of ‘primary psychic roles’ but the scene of a continual construction and dissolution of identity for each individual and for the family as a whole.”39 The family that had seemed unsteadily whole at the beginning of the play, all in good humor after breakfast, progressively loses its bonds through the day and night, until at the end each member is as far from the others as can be, and yet in their shared distance they have something in common, something that makes them one. The family is complete—completely fractured. The play is finished—endlessly. In a sense they have become transparent to one another, fully revealed to the degree that they see through one another and are seen through, as if they are, like the audience, witnesses to a drama in which they can take no action even though they are deeply implicated.

At the time O’Neill wrote the scenario for the play, he imagined Mary’s final scene proceeding somewhat differently from the moment when Edmund attempts to speak directly with her about his diagnosis. At first, she converses with him more directly, following the family pattern of pity and resentment, guilt and blame, hatred and love, as the others have done, but then she pulls away, using some key terms not evident in the final script:

But you might as well give up trying now—you can’t touch me now—I’m safe beyond your reach. You can’t make me remember, except from [the] outside, like a stranger—audience at a play—the real may make her cry but the events and tears [are] part of [the] play, too—she [is] not really hurt—and anyway I won’t remember anything now tonight except what I want to remember.40

These notes move from first person (“me”) to third (“her”) suddenly, just at the moment when the involved noninvolvement is conceptualized in terms of an audience at a play. By the end (approaching midnight in evening performances of the play, to match the midnight of the fourth act), the strange “outside” condition of being an audience has become “real” for her and all the characters, even as the actual audience members might have come to feel part of the family. Everyone is a spectator at the end of the play, and the spectacle is all in the past, leaving only the night itself.

Then it begins again the next evening or at the next reading, with one production after another, audience upon audience. Generations of students by now have read the play, often connecting with Edmund’s point of view, still reading Nietzsche, still in touch with that impulse to go to sea or “be always drunken” or write a play. Then, perhaps a year or a decade later, after a rereading, they might identify with Jamie’s point of view—bitter, frustrated, angry. Some will look for ways to express that. And maybe, after many years, they will recognize a world peopled by James Tyrones, whose stories are of success that amounts to failure, bold quest that leads to loss of soul. In Tyrone is the parable of a child who had to grow up fast, only to become an adult who clings to youthful fantasy. Where is youthful hope, where is the wisdom of age in such a life? Similarly, a whole life’s experience can be felt in Mary Tyrone, but on one reading the reader might connect with her naïveté, then again with her deceptiveness or compulsion or despair. In her, too, the child is in the adult, and the adult is in the child. There’s a son net in all that, as well, or a cautionary tale or an essay for Psychology 101. Wherever you stand in life, at the end of the play, dark as it is, there is something to say the next day, maybe even a play to write.

Long Day’s Journey is the accumulated sum-total of all those plays. It is a play a reader can grow through. Edmund at twenty-four is a product of Eugene at fifty-two, who, like Mary and Tyrone, understood his own failure to establish a real home to reflect on. He also had two disappointing sons, rueful reflections on great promise and past celebrity. One, like Edmund, seemed adrift and aimless, and the other, about a decade older, like Jamie, seemed poisonously abusive of his great promise. O’Neill also confused wife with mother, Virgin Mary with Fat Violet, except when all women seemed entirely alien. Yet he was able to come to a recognition, literally to know himself again and, as he says in the dedication, “to face [his] dead at last and write this play—write it with deep pity and understanding and forgiveness for all the four haunted Tyrones.” For his family and himself he could bring some kind of closure, such as one needs to make a proper memorial. Long Day’s Journey sits on O’Neill like the perfect tombstone, both expressing and honoring him.

All of that might seem as distant as a dusty biography, a mere footnote on bygone genius, but the family O’Neill depicts so precisely in 1912 is the sort of family we know even better a century later, when addiction tears at the domestic fabric, when adult children find themselves living at home with no prospect of independence, when religious faith seems for many like a hazy memory, when the fortunes so readily gained in the recent past fail to establish happiness in the present, when the longing to be at one with the natural world paradoxically coincides with a suicidal despair, and when great poetry, music, and plays no longer seem to offer transcendence, as they did once. O’Neill seems to have understood in 1912 that a different kind of art was going to become necessary for him to survive in a world without home. It took him twenty-eight years to see the problem as clearly as he does in this play, only by then the problems that had been personal in his youth had become widespread in the world. Long Day’s Journey Into Night suggests the new kind of art that would be necessary, and it remains necessary today to complete the journey, as midnight again approaches. Who will become the Edmund of now?

1. As early as 1920 he wrote to the critic George Jean Nathan about the “faith” by which he was living: “That if I have the ‘guts’ to ignore the megaphone men and what goes with them, to follow the dream and live for that alone, then my real significant bit of truth and the ability to express it, will be conquered in time—not tomorrow nor the next day nor any near, easily-attained period but after the struggle has been long enough and hard enough to merit victory.” O’Neill to Nathan, June 20, 1920, in “As Ever, Gene”: The Letters of Eugene O’Neill to George Jean Nathan, ed. Nancy L. Roberts and Arthur W. Roberts (Rutherford, NJ: Associated University Presses, 1987), 41.

2. “I’m a bit weary and disillusioned with scenery and actors and the whole uninspired works of the Show Shop. . . . The ideas for the plays I am writing and going to write are too dear to me, too much travail of blood and spirit will go into their writing, for me to expose them to what I know is an unfair test. I would rather place them directly from my imagination to the imagination of the reader.” O’Neill to M. Eleanor Fitzgerald, May 13, [1929], Selected Letters of Eugene O’Neill, ed. Travis Bogard and Jackson R. Bryer (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 338–339.

3. In a 1925 letter to the historian of American drama Arthur Hobson Quinn, O’Neill repudiated those who would try to assign him to one or another of the contemporary “schools” (e.g., naturalist, romanticist), and then he declared: “But where I feel myself most neglected is just where I set most store by myself—as a bit of a poet who has labored with the spoken word to evolve original rhythms of beauty where beauty apparently isn’t—Jones, Ape, God’s Chillun, Desire etc.—and to see the transfiguring nobility of tragedy, in as near the Greek sense as one can grasp it, in seemingly the most ignoble, debased lives. And just here is where I am a most confirmed mystic, too, for I’m always, always trying to interpret Life in terms of lives, never just lives in terms of character. I’m always acutely conscious of the Force behind— (Fate, God, our biological past creating our present, whatever one calls it— Mystery, certainly)—and of the one eternal tragedy of Man in his glorious, self-destructive struggle to make the Force express him instead of being, as an animal is, an infinitesimal incident in its expression. And my profound conviction is that this is the only subject worth writing about and that it is possible— or can be!—to develop a tragic expression in terms of transfigured modern values and symbols in the theatre which may to some degree bring home to members of a modern audience their ennobling identity with the tragic figures on the stage. Of course, this is very much of a dream, but where the theatre is concerned, one must have a dream, and the Greek dream in tragedy is the noblest ever!” O’Neill to Quinn, April 3, 1925, Selected Letters, 195.

4. O’Neill to George Pierce Baker, July 16, 1914, ibid., 26.

5. O’Neill to Nathan, August 26, [1928], “As Ever, Gene,” 84.

6. Tony Kushner, “The Genius of O’Neill,” Eugene O’Neill Review 24 (2004): 248–256. Kushner’s essay was originally published in the Times Literary Supplement in 2003.

7. Dr. Gilbert V. T. Hamilton, a psychoanalyst whom O’Neill saw in 1925–1926, said, “There’s a death wish in O’Neill.” Arthur and Barbara Gelb, O’Neill (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1962), 597.

8. Doris Alexander, Eugene O’Neill’s Creative Struggle: The Decisive Decade, 1924–1933 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992), 64.

9. Volume 34, no. 1 (2013) of the Eugene O’Neill Review is filled with critical and historical discussions of Exorcism, including its implications for Long Day’s Journey.

10. Travis Bogard, Contour in Time: The Plays of Eugene O’Neill, rev. ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988). Bruce J. Mann connects the play to the tradition of “creative autobiography,” as identified by M. H. Abrams, including works like Augustine’s Confessions and William Wordsworth’s Prelude, in order to address what he calls the “presence” of O’Neill as a sort of fifth character in the play. “O’Neill’s ‘Presence’ in Long Day’s Journey into Night,” in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night: Modern Critical Interpretations, ed. Harold Bloom, 2nd ed. (New York: Chelsea House, 2009), 7–18.

11. Virginia Floyd, ed., Eugene O’Neill at Work: Newly Released Ideas for Plays (New York: Frederick Ungar, 1981), 181.

12. Ibid., 180.

13. Ibid.

14. Quoted in William Davies King, Another Part of a Long Story: Literary Traces of Eugene O’Neill and Agnes Boulton (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010), 14.

15. Floyd, O’Neill at Work, 181.

16. Eugene O’Neill, Work Diary, 1924–1943, 2 vols., ed. Donald C. Gallup (New Haven: Yale University Library, 1981), 2:351.

17. Ibid., 2:372.

18. The “dead mother” is a concept introduced by André Green in On Private Madness (London: Karnac, 1986), 142–173; a recent use of the term in reference to Long Day’s Journey can be found in Harriet Thistlethwaite’s “The Replacement Child as Writer,” in Sibling Relationships, ed. Prophecy Coles (London: Karnac, 2006), 123–151. For a more general psychoanalytic discussion of Long Day’s Journey, see Walter A. Davis, Get the Guests: Psychoanalysis, Modern American Drama, and the Audience (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994); and Philip Weissman, Creativity in the Theater: A Psychoanalytic Study (New York: Delta, 1965).

19. An interesting discussion of O’Neill in relation to the emergence in America of “depth psychology” can be found in Joel Pfister, Staging Depth: Eugene O’Neill and the Politics of Psychological Discourse (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995).

20. This document is in the O’Neill collection of Dr. Harley Hammerman and can be found on his website: eOneill.com.

21. Louis Sheaffer, O’Neill: Son and Playwright (Boston: Little, Brown, 1968), 506.

22. The words used in the play to describe Mary’s wedding dress seem to have been written by Carlotta, who may have had the wedding dress from her first marriage in mind. Floyd, O’Neill at Work, 296.

23. Doris Alexander, Eugene O’Neill’s Last Plays: Separating Art fr om Auto biography (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2005). Many others have paid close attention to the discrepancies, notably the biographers Arthur and Barbara Gelb, Louis Sheaffer, and Stephen A. Black.

24. S. J. Woolf, “O’Neill Plots a Course for the Drama,” New York Times, October 4, 1931, reprinted in Conversations with Eugene O’Neill, ed. Mark W. Estrin ( Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1990), 117. A drama professor at Ohio University wrote to O’Neill in the spring of 1940 to inquire about two different versions of the Monte Cristo scripts, which he was comparing in preparation for a production of the play. O’Neill, who a few years earlier had donated his father’s copy of the script to the new Museum of the City of New York, was at that time finding himself unable to resume work on Long Day’s Journey because he was obsessed with the war news, but he took time to respond to Robert G. Dawes: “The deliberate kidding approach to old melodramas is pretty stale stuff now. It belongs to the radio comedian. Monte Cristo, produced as seriously as it used to be, will be amusing enough to a modern audience without any pointing for laughs. And, played seriously, it should also have an historic interest for the student of Americana, as the most successful romantic melodrama of its time, and one of the most successful plays of all time in America. For over twenty years my father took it all over this country, to big cities and small towns, in a period when nearly every place on the map had a theatre. The same people came to see it again and again, year after year. This is hard to believe, when you read the script now, even considering the period. The answer, of course, was my father. He had a genuine romantic Irish personality—looks, voice, and stage presence—and he loved the part. It was the picturesque vitality of his acting which carried the play. Audiences came to see James O’Neill in Monte Cristo, not Monte Cristo. The proof is, Monte Cristo never had much success as a play at any time, either here or abroad, except for the one dramatization done in this country by him. He bought that outright for very little, because no one believed there was any money in it. / I’m afraid you’ll find in producing it that Monte Cristo without a James O’Neill is just another old melodrama, better than most of them, but with little to explain how it could ever have had such an astonishing appeal for the American public.” O’Neill to Dawes, June 3, 1940, in Selected Letters, 505.

25. O’Neill did not have faith in the theater artists of his day to realize his artistic intentions. As early as 1924, he told an interviewer: “I hardly ever go to the theater, although I read all the plays I can get. I don’t go to the theater because I can always do a better production in my mind than the one on the stage. . . . Nor do I ever go to see one of my own plays—have seen only three of them since they started coming out. My real reason for this is that I was practically brought up in the theater—in the wings—and I know all the technique of acting. I know everything that every one is doing from the electrician to the stage hands. So I see the machinery going round all the time unless the play is wonderfully acted and produced. Then, too, in my own plays all the time I watch them I am acting all the parts and living them so intensely that by the time the performance is over I am exhausted—as if I had gone through a clothes wringer.” “Eugene O’Neill Talks of His Own and the Plays of Others,” New York Herald Tribune, November 16, 1924, reprinted in Estrin, Conversations with O’Neill, 62–63.

26. “O’Neill’s Diagram,” reproduced in Sheaffer, O’Neill, 505.

27. Agnes Boulton, Part of a Long Story: “Eugene O’Neill as a Young Man in Love,” ed. William Davies King ( Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011), 192. Ella added: “I think Eugene is going to be the same about you.”

28. Sheaffer, O’Neill, 89; see also Louis Sheaffer, “Correcting Some Errors in Annals of O’Neill (Part 1),” Eugene O’Neill Newsletter 7:1 (1983): 17–18.

29. See Robert A. Richter’s article on New London and Brian Rogers’s on Monte Cristo Cottage in Robert M. Dowling’s Critical Companion to Eugene O’Neill, 2 vols. (New York: Facts on File, 2009), 2:673–677, 662–666.

30. Dowling, Critical Companion, 1:270.

31. O’Neill, Work Diary, 2:403–404.

32. Carlotta wrote in a November 6, 1955, letter to Dudley Nichols: “Gene insisted that if I published ‘Long Day’s Journey Into Night’ I must insist that the ‘inscription’ be published also,—& no other ‘foreword’ or ‘introduction’ be used in place of it or with it. I did just that. He claimed that the ‘inscription’ showed what his mood was when writing it—& what hell he went through!” Quoted in Judith E. Barlow, Final Acts: The Creation of Three Late O’Neill Plays (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1985), 180 n. 60.

33. O’Neill to Kenneth Macgowan, June 14, 1929, in “The Theatre We Worked For”: The Letters of Eugene O’Neill to Kenneth Macgowan, ed. Jackson Bryer (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982), 191.

34. Sheaffer, O’Neill, 635.

35. Carlotta Monterey O’Neill to Norman Donaldson, December 18, 1956. I own this manuscript. Again, some would dispute her version of how and why the play came to light in 1956.

36. Michael Hinden, Long Day’s Journey into Night: Native Eloquence (Boston: Twayne, 1990), 84, 87, 89.

37. There are dissenters to this point of view on Long Day’s Journey, notably Matthew Wikander, who views O’Neill’s late plays as “acts of aggression and revenge rather than of forgiveness and understanding.” Wikander, “O’Neill and the Cult of Sincerity,” in Cambridge Companion to Eugene O’Neill, ed. Michael Manheim (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 232.

38. Selected Letters, 506–507.

39. Kurt Eisen, The Inner Strength of Opposites: O’Neill’s Novelistic Drama and the Melodramatic Imagination (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1994), 126.

40. Floyd, O’Neill at Work, 291.