The stage history of Long Day’s Journey Into Night might not have been. O’Neill made it clear that the play must never be produced and that it should be published only in the distant future. Thus, the history of so many unforgettable productions and films of this masterpiece must begin with Carlotta O’Neill, who decided to override her late husband’s wishes and grant performance rights to the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm.1 The world premiere was February 10, 1956, less than three years after O’Neill’s death. Carlotta explained that her unusual decision was made in gratitude to the Swedes for how they had consistently honored O’Neill’s work. Some suspected that she had, by turning to a European theater company, eluded a potential legal challenge in the United States courts to her apparent defiance of O’Neill’s expressed wish. She asserted that he had changed his mind near the end of his life and, in any case, that he had unmistakably given her the authority to manage his estate, so the rights to Long Day’s Journey were now in play.

A Broadway production followed within months, though not before the play was again staged in Germany and Italy. It was notably strange that an American masterpiece would speak first to audiences in foreign translations. Further vexing the New York theatrical and literary establishment, for the American premiere Carlotta O’Neill chose José Quintero, a young off-Broadway director. Earlier that year Quintero had directed an eye-opening revival of The Iceman Cometh. The “Hickey” in that production, a relative newcomer named Jason Robards, was cast as Jamie in Long Day’s Journey, and a complete unknown, Bradford Dillman, was cast as Edmund, with Carlotta’s approval (she said he reminded her of Gene). Many Broadway veterans coveted the roles of Tyrone and Mary, but there was no question in Quintero’s mind that they would go to anyone but the Broadway legends “the Marches,” Fredric March and Florence Eldridge, who had

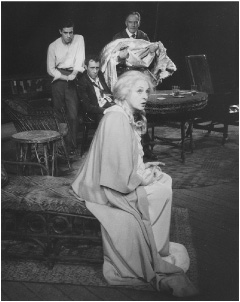

Florence Eldridge as Mary Tyrone with Jason Robards as Jamie, Bradford Dillman as Edmund, and Fredric March as James Tyrone in the final scene of the Broadway premiere production of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, which opened November 7, 1956. (Photograph by G. Mili; Eugene O’Neill Collection, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

been married since 1927 and often appeared onstage together. The financing also came from Broadway stalwarts, including Roger L. Stevens. The production, which opened in New York on November 7, 1956, proved to critics and audiences that the play not only deserved but needed to be seen as well as read, and generations of theater artists have found ways of creating the play anew each time the curtain opens on act 1.

Before the first production, when the play was available only in published form, the critic and director Harold Clurman predicted that some would call the play impractical, but he reminded his readers that O’Neill’s plays worked better on the stage than on the page. He declared Long Day’s Journey “the testament of the most serious playwright our country has produced,” adding, “For in a time and place where life is experienced either as a series of mechanistic jerks or sipped in polite doses of borrowed sophistication . . . O’Neill not only lived intensely but attempted with perilous honesty to contemplate, absorb and digest the meaning of his life and ours. He possessed an uncompromising devotion to the task he set himself: to present and interpret in stage terms what he had lived through and thought about.” Directors who undertake this play have had to discern those “stage terms” within a script crafted for a reader. Clurman articulated the particular challenge the work would pose for actors: “Every character speaks in two voices, two moods—one of rage, the other of apology. This produces a kind of moral schizophrenia which in some of O’Neill’s other plays has necessitated an interior monologue and a speech for social use . . . or . . . two sets of masks. In this everlasting duality with its equal pressures in several directions lies the brooding power, the emotional grip of O’Neill’s work.”2 Another critic commented that O’Neill had created not four but eight principal characters in this play because each family member has a doppelgänger, an alter ego, as defined by the dualities of love and hate, innocence and guilt, and past and present.3

Several New York critics traveled to Stockholm to see the world premiere, performed in Swedish. The power of the play, especially in the performance of Inga Tidblad as Mary, such that one critic identified its climax as the end of the third act, shone when the power of the addiction opposes the love expressed by Tyrone in a battle for Mary’s soul.4 After the New York opening, Henry Hewes wrote:

Long Day’s Journey Into Night is not so much a “play” as a continuously absorbing exegesis of Mary Tyrone’s line, “The past is the present, isn’t it? It’s the future, too. We all try to lie out of that but life won’t let us.” O’Neill steers as far from conscious plots and phony resolutions as he can. In their place he offers character development. Each of the quartet advances from morning’s surface jocularity into evening’s soul-shaking revelations of self-truth. . . .

For those who are familiar with some of the details of O’Neill’s tragic life and with the twenty-five full-length plays that gained him his reputation as America’s greatest playwright, this merciless autobiography is enormously interesting. But even for those who are not, there is a breadth to Long Day’s Journey Into Night that may make it the most universal piece of stage realism ever turned out by an American playwright. For doesn’t it expose the forces that work both to unite and tear asunder all human groups? What family does not have its private disgraces, its nasty recriminations, its unforgotten grievances? What family is not obliged to put up with some sort of unreasonable behavior from its breadwinner, some selfcenteredness from its dominant figure? What brothers or sisters do not possess a pinch of jealousy that pollutes their love of each other? . . . All these things O’Neill has put into this play, baldly and directly. The terror it inspires comes not from the day’s events, but from the gradual intensification of its torment and violence as night moves in.5

Even among those who had reservations about the play (length and repetition were often mentioned), praise for the actors and for Quintero’s subtle directing was unanimous. Quintero has left in his memoir an invaluable account of the work he did in bringing this play to the stage. He records an inner dialogue, as it were, of the actors finding their characters in conversation with him. He knew that the play was a masterpiece when he first read it, and he knew that his opportunity as its first American director could not be exceeded in importance.6 Theodore Mann, who was one of the producers, wrote that at the New York opening there was total silence when the actors stood for the curtain call. He recalled that it took a minute or two before the audience began “applauding wildly. And then they started approaching the stage, en masse, applauding and vociferously shouting ‘Bravo!’ Audiences did not stand up in theatres in the fifties. I think this might have been the start of the standing ovation on Broadway.”7 The Pulitzer Prize, two Tony Awards (best play and best actor for March), the Drama Critics’ Circle Award, and countless glowing reviews certified that this opening was a momentous event in American theater. Quintero went on to direct numerous other O’Neill plays over the next three decades in a still-unclosed era that has been called “the O’Neill revival.”

Brenda Murphy’s book in the Plays in Production series encapsulates much of the history of how this play was staged in New York and elsewhere worldwide in its first four decades. The book’s appendixes catalog some ninety professional productions through 2000 and six versions on film or video, and the pace has continued unabated since then. Countless regional and community theaters have produced the play at least once. The bibliography of critical discussions of the production history would fill an entire volume.8

Long Day’s Journey has largely resisted boldly conceptual interpretations and adaptations, owing to restrictions by the guardians of O’Neill’s rights. Stage directors have been hindered from much cutting or manipulation of the script, and film and television directors have been blocked from redeveloping the script as a screenplay. Sidney Lumet’s 1962 film included one short scene between Tyrone and Jamie in the garage on the property, and several productions have made a little use of the front porch, but mostly the work remains in the four walls of the living room and the four acts of the play. Even so, small changes can make for significant differences in emphasis and thus interpretation. At issue are the casting and blocking, the costumes, setting, and props, but above all the work done to build distinct characters who combine to create that subtle structure, the Tyrone family at home.

Internal references seem to demand that the play be set in 1912 in New England. Some productions have supplied scenic details based on the O’Neill house in New London, as well as costume and makeup details from O’Neill family photographs. Others have steered away from treating the play as a documentary of sorts, but the story still seems to require a realistic mise-en-scène.9 Some productions emphasize the climactic development of the play to underscore the tragic insight uniquely revealed at the end of this particular long day, while others emphasize the continuum, the existential bind in which the characters, like all human beings, are locked: the difficulty of going on being oneself in spite of life’s cruel effects.

The play offers four exceptionally rich characters for actors to interpret, and it seems designed to give equal depth and focus to each. Most productions, however, suggest greater centrality for one or another of the characters, and significant differences in interpretation result.10 A discussion of each character in turn highlights issues that arise in performing the play.

When the role of Tyrone is taken by a well-known actor (such as Fredric March or Laurence Olivier), he often seems to be the dominant member of the family and is revealed by the end as the key causal factor in the family’s trials. The very same theatricality that made Tyrone a romantic figure for the young Mary, simultaneously winning him popular acclaim and bloating his self-esteem, might also be taken for the inauthentic, even deceitful tendency of an American society insistent on selling the illusion of maximum happiness for a tidy profit. A commanding actor, especially one who brings an element of celebrity to the production, will inevitably highlight the way showmanship has worked for and against the happiness of the Tyrone family. Social theorists have long debated the degree to which self-interest, even selfishness, is required for success within free-enterprise capitalism. Tyrone wants to believe that his self-advancement has been pursued for the good of his whole family, but Jamie especially hears a hollow idealism in his father’s success, since it has come at a direct cost to his mother, himself, and now Edmund.

In 1906, at the time O’Neill was beginning to think seriously about the role of the modern writer, he absorbed George Bernard Shaw’s critique of how ideals—belief systems enlisted in the name of morality, progress, beauty, civility, and so on—might stand in the way of an accurate perception of reality or something still deeper. In a 1924 tribute to August Strindberg, whom he revered above all other modern dramatists, O’Neill wrote:

Yet it is only by means of some form of “super-naturalism” that we may express in the theater what we comprehend intuitively of that self-defeating self-obsession which is the discount we moderns have to pay for the loan of life. The old “naturalism”— or “realism” if you prefer . . . no longer applies. It represents our Fathers’ daring aspirations toward self-recognition by holding the family kodak up to ill-nature. But to us their old audacity is blague; we have taken too many snap-shots of each other in every graceless position; we have endured too much from the banality of surfaces. We are ashamed of having peeked through so many keyholes, squinting always at heavy, uninspired bodies— the fat facts—with not a nude spirit among them; we have been sick with appearances and are convalescing; we “wipe out and pass on” to some as yet unrealized region where our souls, maddened by loneliness and the ignoble inarticulateness of flesh, are slowly evolving their new language of kinship.11

The fine phrases and artful poses of his father’s theater would never touch those depths, but as he suggests here, neither would the gratuitously sordid displays of the naturalistic theater. One might argue that Long Day’s Journey itself operates according to that “super-naturalism,” perhaps especially in the long journey taken by Tyrone.

The romantic values of Tyrone’s theater, in which the battle between good and evil is often conceived as a conflict of hero and villain, with the villain always losing, present a myth aligned with idealism. His sons adopt instead the pessimistic outlook of the decadent writers, and Mary has her own form of idealism in the remnants of her Catholic faith, which aims at separation from the fallen world. At the start, Tyrone believes he is the realization of an American success story, an embodiment of national ideals. He has freed himself from poverty by adapting to his American environment, refashioning himself as a hero, and fulfilling the promise by getting rich. In the process, he flatters himself for having married a woman who upholds idealism in her religious and cultural values, establishing a home sweet home, and earning friends and respect as a successful artist.

Of course, his sons radically disagree, seeing him instead as a figure of greed, materialism, self-indulgence, egotism, and fakery—an embodiment of the sordid reality behind capitalistic enterprise. Mary, too, has lost her romantic belief in her husband, adopting a sometimes harshly realist view of his behavior. Productions that concentrate on Tyrone often seem to explore the possibility that the seed of tragedy in this family can be found in his success story, a version of the American Dream that the play might be construed to criticize—even in the rueful words of Tyrone himself (“What the hell was it that I wanted to buy . . .” [153]). The way Edmund hears his father’s saga, with amused pity at the cruel joke that life plays on us, seems to promote this Tyrone-centered perspective on the play. What Tyrone has “never admitted . . . to anyone before” (152), the recognition that he sold his soul by misusing his talent for profit, begins a sequence of revelations that all members of the family have lost their souls because of conditions in the modern world (materialistic values; chemical substitutes for vitality; abandonment of spirituality for sensuality, pride for self-hatred, beauty for decadence, and family for ego). These revelations might be the “secret” Edmund sees and enables us to see in his play. Perhaps by the end of the play, having witnessed the disconnect between the heroic and the pathetic in his family, Tyrone himself sees the need for that “new language of kinship” called for by O’Neill.

Jamie is insistently contemptuous of Tyrone, and Mary and Edmund also voice bitterness toward him, so it becomes a challenge for the actor to keep Tyrone likeable for the audience. Fredric March, who created the first Tyrone for an English-speaking audience, marked his script with many handwritten notes, including the following: “For all his bluster (& he should bluster in a fine, Irish way) he is something of a gentleman—he is self-made, surely—but so is Gene Tunney [a famous boxer] & so is Jim Cagney [a hard-nosed Hollywood actor].” The New York Times review nicely captures the complexity of the character March devised: “Petty, mean, bullying, impulsive and sharp-tongued, he also has magnificence—a man of strong passions, deep loyalties and basic humility.” For a generation, all other performances of Tyrone were compared to March’s, with Laurence Olivier “more domestic, perhaps more human,” Jack Lemmon more likeable (“a decent man with some indecent traits, a faded dandy aware of his self-delusions, a man as much victim as victimizer”), Jason Robards more ferocious, Anthony Quayle weaker, William Hutt more sympathetic, and so on.12

Productions that center on Mary seem to view her downfall as the most extreme and poignant of the four characters, thus conceiving the play more as a tragedy than a critique. Over the course of the play we assemble an image of Mary in the past as a victim—at least, that is how she perceives herself. Formerly a figure of innocence and purity, faith in the church, love of music, and family unity, she then descended into a lonely, godless, inauthentic, and degraded world in which drug addiction barely masks the pain of alienation from her sense of self. Try as she may, she is unable to escape this overwhelming condition of downfall. A crucial question, to which different performers have given different answers, is how active she is in this descent. Is she weak, a liar, helpless in the face of circumstances that doom her? Or is she someone who uses a facade of innocence to mask her angry rejection of the demanding world and her preference for release into chemical solitude? Florence Eldridge, who played Mary at the Broadway premiere, left notes stating that Mary was a “victim, not only of her life but of her own inadequacies, and must be played as an immature person.” In Eldridge’s portrayal, Mary’s presentation of herself was given a deliberately practiced, rhetorical quality, as if she were delivering a performance of her own innocence and victimhood. In the 1958 London premiere, Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies took Mary’s behavior into the realm of culpability, making her relapse into addiction, in the words of one critic, “seem a negation of all honesty, the final murder of truth,” and Jessica Lange, in 2000, took this interpretation even further, creating a Mary whom one critic described as “an emotional sniper . . . a clinging woman with a killer emotional backhand.” Geraldine Fitzgerald, in contrast, found a way to construct Mary’s actions as an aggressive assertion of the maternal. Her Mary was “not trying to escape fr om something so much as going toward something—a place where her son could not be in danger—in other words, a reality of her own creating.”13

O’Neill does not specify when Mary takes the first dose of morphine in this particular relapse. From the very beginning of the play, Mary is an object of scrutiny who is herself obsessively concerned about her appearance, but she might already have something to conceal. Did she use the drug the previous night in the spare room or that morning before breakfast in order to keep up an illusion of calmness in the face of stressful circumstances? Has she been discreetly and unobtrusively using the drug for days or even weeks to help her cope with Edmund’s gradually worsening health? Or is the first act of the play the occasion when relapse becomes unavoidable? Each performer must develop a sense of the emotional logic leading to her break with the family’s wishes, and the effect of a mind-altering substance must be factored into every moment of the performance.14 The same is true of the men, who drink an astonishing amount of whiskey over these eighteen hours. But we must remember that O’Neill could write from his own experience about the effect of heavy drinking (though he had been sober, with only a few relapses, for about fifteen years when he wrote the play), whereas he understood the effect of morphine addiction only from observation and distant memory of his mother. Different performances suggest varying ways the drug might affect Mary.15 Similarly, different productions suggest varying degrees of alcoholic influence affecting the men.16 But Mary is usually more extremely in her own world.

Her isolation as a woman, which is only heightened by her scene with Cathleen, suggests a feminist angle on the play to some directors and performers.17 Several productions over the past decade have looked at the condition of Mary as a woman in a male-dominated world, notably the Tony Award–winning performance by Vanessa Redgrave in 2003, which created the most accessible and pitiable Mary Tyrone to date. Others, however, have felt that O’Neill effectively locks Mary into the “spare room” of this drama by displacing her, mentally and physically, from the stage. The premiere production in Sweden heightened the sense that O’Neill’s depiction of Mary might be hostile. One critic wrote: “This might almost be called the Strindbergian interpretation of O’Neill: compulsively insisting with all the Swedish playwright’s demonic power that, where there is a vortex of destruction and self-destruction, a woman must be near the center.”18

In contrast, feminist critic Geraldine Meaney reads the play as illustrative of a modern and postmodern “crisis in figurability,” specifically a loss of maternal reality, leaving a world in which representation itself is destabilized. She interprets Mary as an effective expression of the tension between modernism and postmodernism in O’Neill’s writing and the literature of his era: “As lost origin, the loss of which denies the possibility of the original or truthful, [Mary] symbolises what modernism mourned, sought and feared. In Long Day’s Journey Into Night, the pain of loss, the understanding that the loss is necessary and the struggle to articulate from the other side of the unknown do battle. Only in the closing speech does it succumb to the nostalgia which besets modernism. In this respect O’Neill’s conclusion is reminiscent of Joyce’s conclusion to Ulysses. Both finally fake the voice of the (M)Other.”19 Judith Barlow also reads Mary’s character as much in terms of her absence as her presence within the play. Considering that O’Neill in his plays habitually equates the feminine with the maternal and often characterizes his women as either Madonnas or whores, she writes, “In part, Mary Tyrone’s dilemma is that she has found herself in an O’Neill play.” Nevertheless, she identifies Mary as O’Neill’s “most fully realized female character,” and argues: “Mary Tyrone is finally neither mother nor virgin, and in this lies much of the tragedy of the Tyrone family. The men demand that she be a mother in all senses of the word, but she cannot and will not fulfill that role. Yet even in her drugged stupor she cannot regain the virginal innocence for which she so desperately yearns.”20

In some productions, the character of Jamie seems surprisingly to stand out, though reasons might be found in how O’Neill constructs the family. Each of the others has some happy memory, a little fire by which to warm themselves in memory. Mary has the peace and acceptance of the convent, Tyrone the thrill of acting with Booth, Edmund the ecstatic experience of oneness with the sea, but Jamie has only a corrupted remembrance of being united with his mother before the births of Eugene and Edmund, and he draws little comfort from that insubstantial memory.21 Having so little of the light in his soul, he plunges further than anyone into the dark, even the demonic. Jamie twice quotes Iago, the infamous antagonist in Shakespeare’s Othello, twice provokes a physical attack, and usually prefers to play the role of antagonist or even villain. Near the end of a typical melodrama, the hero comes face to face with the villain, whose challenge the hero must overcome to reach a happy ending. Long Day’s Journey is no melodrama, but O’Neill plays with this structural feature in Jamie’s revealing of himself as one who deeply hates as well as loves his brother—a backstabber as well as a pal. Productions that give prominence to Jamie might seem to imply that he is the heart of darkness, a glimpse of the satanic or death itself, and yet, for all that, the most loveless and woeful of the characters, most in need of “deep pity and understanding and forgiveness,” but perhaps beyond reach. To some degree, O’Neill must demonize Jamie to provide a climactic moment to the fourth act. O’Neill still also carried anger toward his brother for things that happened in the final year of Jamie’s life, when alcoholism was literally poisoning his mind.22 It has been suggested that O’Neill compensated for using Jamie as a villain in Long Day’s Journey by next writing A Moon for the Misbegotten, which centers more sympathetically on the story of Jim Tyrone, as he is named in that play.

Jason Robards, who played Jamie in the Broadway premiere and later in the Sidney Lumet film, set the standard for all-out passion in the fourth act confrontation with Edmund. On opening night, he brought the show to a standstill with his “think of me as dead” speech, with the audience audibly expressing its disturbed feelings. Later he said, “It’s easy to do—if you’re an actor who knows his craft .”23 This anecdote expresses one of the paradoxes of Jamie’s part since he makes such a point of rejecting every aspect of his father’s art. Robards’s own father was a famous actor of Irish heritage, so he inevitably brought some family associations to the part, though he was not a Method actor and in general disparaged those who brought personal material to the art of acting. But it is notable that Jamie, seemingly against his will, is the character most prone to play on the theatricality of his scenes in the play—to parody his father’s acting style or quote poetry or highlight dramatic ironies, as in his hostile interjection, “The Mad Scene. Enter Ophelia!” (174). Kevin Spacey took Jamie to the other extreme, portraying him as a weak man, sunk in depression, who backs away from involvement and is, by the final line, asleep—dead to the world. Philip Seymour Hoffman similarly gave Jamie an untheatrical yet compelling quality. In the first act, the audience could see evidence of Jamie’s deep, loving bond with his mother, making the rapidly growing alienation all the more painful. The dulling effect of chronic drinking, intensified during this long day, could barely still the pain in his tortured depths. Other Jamies, such as Ulf Palme in the Swedish premiere and Dennis Quilley, who played opposite Olivier, found “cruelty” in the character, the violence of a creature so lacking in resources.

Rarely does Edmund come across as the key character, which might seem odd since virtually every production reminds the audience in the program and publicity that the play is autobiographical.24 Yet even Edmund declares that his outspoken moments, when he might define for us his point of view, represent little more than “stammering.” He is the listener who learns more than anyone else during this day and night about his implication in the family’s tragic history, but his actions, like his diseased body and corrupted will, are weak. Travis Bogard writes that Edmund “remains a participating observer, a little apart, an eavesdropping creature of the imagination,” and yet his passivity might be said to stand in ironically for the chief action of the play.25 At a key moment during act 1 he is absent from his duty to watch his mother, and he’s not there for dinner or for his father. More generally, he has not lived up to the expectation that his life would make up for the lost baby, and recently he has not been present at all, indeed has made an effort not to be at all. Yet he is a transformative character, perhaps the only one capable of metamorphosis. In 1975, Jason Robards, who was directing a production for the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, told an interviewer: “It’s about the growth of Edmund—of O’Neill—of his finally cutting the cord away from his mother.” In 1988, Campbell Scott, playing Edmund in a production in which his mother, Colleen Dewhurst, took the part of Mary, managed to put the focus of the last act “more on the encounter between Edmund and his father than on the confrontation between the brothers.”26 Nevertheless, remarkably often reviews of Long Day’s Journey point to the performance of the Edmund character as the weak part of the performance. Is that assessment an inevitability, a flaw, a mistake, or is it a deferral to the moment when Edmund, transformed into the author of this “play of old sorrow,” would reenter the scene as the only one of “the four haunted Tyrones” who could complete the “Journey into Light—into love”? The great Swedish film and stage director Ingmar Bergman’s 1988 production drew attention to this completed journey by having the family all exit the stage at the end, going in different directions, with Edmund last to leave. Edmund picked up a notebook, which had been present throughout the play and from which he had read to his father about his experiences at sea, to suggest that he had more writing to do. As he left the stage, an image of a brightly illuminated tree was projected to suggest the new life that would come of this night.27

Curiously, the actress playing Cathleen almost always receives praise for bringing a welcome note of humor and normality in the otherwise pain-ridden world opened by O’Neill. That said, most productions surprise the audience with how much laughter and, yes, good humor can be generated by each of the characters. From the opening anecdote about Shaughnessy to Tyrone lamenting that he had never known Mary “to drown herself in it as deep as this” and then adding, “Pass me that bottle, Jamie,” O’Neill plays on the proximity of the abyss and the absurd in a way that echoes Shakespeare (Hamlet, King Lear), Strindberg (The Dance of Death), even Anton Chekhov (everything he wrote), and anticipates Samuel Beckett (Waiting for Godot, Happy Days) and Edward Albee (Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf ?).

Of course, a production demands that extraordinary melding of all into a unity, an ensemble that can show, by the responsive art of acting, how these individuals form a family. As in any family, there are shared codes, interlaced memories, patterns of conditioned response and subconscious reaction, as well as distinctive marks of trauma borne unequally by all but by all reconstituted into separate strategies for survival.28 The rehearsal room, in which all this has to be found, must be a place of profound group exploration so that the play can open itself to similar exploration by the audience. For enabling that exploration to take place, we should all thank Carlotta Monterey O’Neill.

Home and the lack of such a place is a theme on which—or in which—Mary Tyrone dwells. She has blissful memories of places where formerly she felt at home and traumatic memories of moving into places that, despite her husband’s efforts, she could not recognize as home (hotels, theaters, the spare room). James Tyrone has lived through a different experience of home and its disruptions, but he prefers to recognize this summer house as an adequate home. The fourth act especially reflects the difficulties the four family members face in finding themselves at home in this space. Each has an entrance (or an exit) that could be taken as a cameo portrait. For this reason, scenic design plays a central role in telling the story.

While writing the play, O’Neill drew a floor plan of the house as he remembered it from 1912 (part of the porch was removed in a later renovation). The drawing is remarkably accurate in its proportions and general layout. The front door, up a broad set of stairs at one end of the long front porch, leads to an entryway from which stairs ascend to the second floor. To the left is a front parlor through which one passes to get to the living room on the opposite side of the house, where most of the play takes place. This room has windows on three sides and a door to the front porch. In it he shows a center table, a small writing table to the side, two other chairs, and a couple of bookcases. O’Neill drew a separate sketch of the room in which he

O’Neill’s two diagrams of the setting of Long Day’s Journey Into Night. The first is a floor plan of Monte Cristo Cottage. The second is more of a stage setting of the living room in which the play takes place. (Eugene O’Neill Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

rearranged the furniture and windows, suggesting a rethinking of the space as a stage set. (Here is a piece of evidence that he was mindful of a possible performance.) He positions the chairs around the center table in a way that orients the scene toward the front wall, which he does not draw in. He seems to indicate a door at the rear of that room, which, according to his stage directions, would lead to the back parlor, where Mary’s piano is located. In the actual house, that parlor is through the side door, and the dining room is beyond that, in the room behind the front stairs.

It is difficult to discern the floor plan of the set for the original Broadway production from production photographs. The designer, David Hays, made no use of the actual floor plan of the house or O’Neill’s diagrams, as he later explained: “I went up to New London to see the types of houses up there and someone showed me photographs of the actual house, but when I drove up there, no one from the management pointed out to me which house it was. I didn’t particularly care. The only thing from the house that came out in the set was a little bit of porch detail, a very small bit of it, quatrefoil, which was outside the windows anyway and was seen by no one but a few people and me.”29

Quintero told Hays to put the stairs upstage right and the door to the garden stage left; also, the room was not to face the street and was to have as little furniture as possible. In other words, he paid little heed to either the actual room or O’Neill’s scene description. Hays mentions that he and Quintero even discussed the idea of setting the play in an entirely different space, such as a screened-in porch.30 Production photographs show partially colored windows in the background, which were used to reveal the sunlight moving from morning to noon to evening to dark night, but little else of the house is apparent. It’s almost an abstract space, with minimal details and an enfolding darkness. The New York critics uniformly praised the set, which Brooks Atkinson described as “a cheerless living-room with dingy furniture and hideous little touches of unimaginative décor.” He added that the “shabby, shapeless costumes by Motley and the sepulchral lighting by Tharon Musser perfectly capture the lugubrious mood of the play.”31

Many directors and designers since then have adhered more closely to O’Neill’s description of Monte Cristo Cottage and studied the actual floor plan for ideas about creating the play’s environment, while others have used little more than furniture—a round table with mismatched wicker chairs, for instance—to encapsulate the domestic environment, with the house itself barely indicated. An exploration of one especially successful design suggests how aspects of the house can articulate the problem of home.

Santo Loquasto was the scenic designer of the 2002 Goodman Theatre production of Long Day’s Journey, directed by Robert Falls, with Brian Dennehy and Pamela Payton-Wright.32 Falls and Dennehy had worked together on the 1999 Goodman production of Death of a Salesman, which later moved to Broadway for a Tony Award–winning run. Dennehy, who is of Irish ancestry and was raised Catholic in Connecticut, wished to resume his “unrequited romance” with O’Neill by playing the role of James Tyrone, and the aim was to take this production in a similar way from Chicago to Broadway.33 Falls’s directing of the play took on new meaning when his mother died during rehearsals of the Goodman production. Loquasto, whose work on Broadway goes back to the Drama Desk Award–winning Sticks and Bones in 1972, had worked with Falls only once before, on Chekhov’s Three Sisters at the Goodman. He had extensive experience with classic and new plays, operas, and dance, as well as two dozen Woody Allen films. He had previously designed sets and costumes for the Hartford Stage Company Long Day’s Journey in 1971, working with an excellent cast (Bob Pastene, Teresa Wright, Tom Atkins, and John Glover), but the design possibilities for that production were limited by the use of a three-quarters staging, so he was delighted to return to the play at the Goodman.34 The production moved to Broadway, opening May 6, 2003, with Vanessa Redgrave taking over as Mary, Philip Seymour Hoff man as Jamie, and Robert Sean Leonard as Edmund. Dennehy continued in the role of Tyrone. It won the 2003 Tony Award for Best Revival, as well as many other awards, and is remembered by many as the production that redefined the play for a new century.

The Albert Theatre at the Goodman was rebuilt in the 1990s from a much older theater and currently seats 856. It features a large and lofty proscenium stage on which Loquasto sought to suggest a modest seaside cottage, impressive from the outside but plain in the interior. A visit to the Monte Cristo Cottage in New London many years earlier gave him a sense of the weather-beaten wraparound porch, the generic doors and windows, the dark paneling and wallpaper done in a

Two images of the stage set for the 2002–2003 Goodman Theatre and Broadway production of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, designed by Santo Loquasto. (Photographs courtesy of Goodman Theatre)

way that would confirm Mary’s attitude about the house’s “cheapness,” as well as its gloominess. In his design, he portrayed the home as “an uninsulated wooden world,” with scrubbed wooden floors, few rugs, and “dark, warm gray walls that would recede in the dark of the evening” to leave the family ultimately in a more abstract, obscure space. He aimed to suggest “an ache about the house.” In this era when production costs run so high that many designers aim for a more minimalist or conceptual design, what is lost is a sense of the specificity, the physicality, the materiality of the structure in which this family lives, all of which is inscribed precisely in Loquasto’s setting. This house is a presence, dismally real yet also expressive of a longing to reach higher, like each of the characters trapped within it.

Loquasto wanted to have a strong suggestion of the physical structure of the house on stage, because the house is effectively a character in the scene. We do not see the events upstairs, but the sound and sight of the dark wooden staircase help us imagine that high. Loquasto

knew O’Neill’s description and diagrams, but he altered several details to tell the story better and to suit the large stages on which the production would be played.

The living room occupied almost the entire downstage area—literally downstage, as the characters had to step from the foyer through one wide passageway down into the room from the front hall (right) and step up through another passageway into the back parlor (left ). The formal front parlor, which O’Neill describes as intervening between the living room and the front hall, instead lay in deep shadow beyond the stairway, barely visible. This allowed the front door to be seen within the unlit front hall. As in Monte Cristo Cottage, the staircase stood opposite the front door. O’Neill calls for a screen door to the porch on the right wall; this is used, for example, by Tyrone in the fourth act when he goes onto the porch to avoid confronting Jamie. Loquasto instead put a door on the back wall at the left . Only a little of the back parlor could be seen; characters crossed through this room to the dining room and kitchen. The two rugs in the living room seemed inadequate—too cheap—to bring warmth to the space, and the strong vertical lines in the set emphasized its stark qualities. Mary’s sense that there is “something wrong” about the house seemed palpable in Loquasto’s design.

The room was set at an angle, showing the window-seated side wall along the front and only a corner of the downstage wall, which gave a glimpse of the weathered clapboard exterior of this seaside house. A strip of the front porch could also be seen on the right. The first three acts showed the passage of the sun on its long day’s journey, with the morning sun coming from the right and the sunset from the left . As in the Sidney Lumet film version of Long Day’s Journey, a rotating lighthouse beam played through the structure at regular intervals in the night scene.

The furniture had a mismatched, inelegant, but not shoddy quality. Tyrone’s chair was the sturdy wooden one at the center table. Along with the center table, the chair had to be strongly reinforced with metal braces to allow Brian Dennehy to step on them to turn out the lights in the overhead fixture in the fourth act. The rest of the furniture was of inexpensive wicker, to show the more insubstantial relation of the other characters to this house. Edmund’s desk, on the left, held some of his books, but the room had only one bookcase, beneath the portrait of Shakespeare, with sets of books and other memorabilia associated with Tyrone. The isolated divan on the right was where Mary sat at the end, looking directly at the audience as she remembered being “happy, for a time.”

Broadway’s Plymouth Theatre, to which the production moved for its 2003 opening, is, like the Albert Theatre, a reconstructed old theater (built in 1917) with a large proscenium stage. These big stages allowed Loquasto to extend the walls of the set to a height of twenty-four feet, creating what Frank Galati described as “a cathedral of sorrow.” Some critics disliked this looming quality, but the expanse of wood paneling enabled Loquasto to suggest in a poetic-realist way many of the sensual and emotional aspects of this oppressive house. The scrubbed grayness of driftwood spoke of the sad passage of time through this space, a simple and natural beauty that had lost luster through wear, as in an Andrew Wyeth painting. Loquasto’s set opened up a shadowy, uninviting interior, one we could well believe was haunted by ghosts among whom you could not help but live—fraught memories of failed aspirations of the harrowing sort that O’Neill and his family knew so well.

1. The artistic director of that theater, Karl Ragnar Gierow, having heard that an unproduced play by O’Neill might be available, took the step of asking Dag Hammarskjöld, the Swedish secretary-general of the United Nations, in December 1954, to inquire whether rights unavailable to American producers might be open to the Swedes. In June 1955, Carlotta told Hammarskjöld she would offer Sweden the play, with no royalties, adding that she would not allow production in the United States. See Brenda Murphy’s O’Neill: Long Day’s Journey into Night, a key resource for this entire discussion of the play in production (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 5. Ample evidence exists to show that on many occasions Carlotta adapted facts to suit her version of reality, so any story of her involvement in the history of Long Day’s Journey or O’Neill more generally should be approached with caution.

2. Harold Clurman, review of Long Day’s Journey, Nation, March 3, 1956, reprinted in O’Neill and His Plays: Four Decades of Criticism, ed. Oscar Car-gill, N. Bryllion Fagin, and William J. Fisher (New York: New York University Press, 1961), 214, 216.

3. Gilbert Seldes, review of Long Day’s Journey, Saturday Review of Literature, February 25, 1956, 16.

4. Frederic Fleisher, review of Long Day’s Journey, Saturday Review of Literature, February 25, 1956, 16.

5. Henry Hewes, review of Long Day’s Journey, Saturday Review of Literature, November 24, 1956, reprinted in Cargill, Fagin, and Fisher, O’Neill and His Plays, 217–218.

6. José Quintero, If You Don’t Dance They Beat You (New York: St. Martin’s, 1988), 203–264.

7. Theodore Mann, Journeys in the Night: Creating a New American Theatre with Circle in the Square: A Memoir (New York: Applause, 2007), 149.

8. Jordan Y. Miller’s Eugene O’Neill and the American Critic (New York: Archon, 1973) records major productions from the premiere through 1972. Madeline C. Smith and Richard Eaton do a similar listing for the years 1973– 1999 in Eugene O’Neill: An Annotated International Bibliography (Jefferson, NC: MacFarland, 2001). Also useful is Jackson R. Bryer and Robert M. Dowling, eds., Eugene O’Neill: The Contemporary Reviews (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), which reprints opening-night reviews of many O’Neill plays.

9. Among the few who have “departed from naturalism” in the staging of the play, the great Swedish director Ingmar Bergman is notable; as one actor in the cast put it, in his 1988 production Bergman aimed “to do it more like a dream that becomes a revelation in the night” (Murphy, O’Neill, 101).

10. One critic saw a rare perfect balance in the 1986 Jonathan Miller production, which was later filmed for television. Although it featured the film star Jack Lemmon as Tyrone, the critic commented: “Never before has the bickering, savaging Tyrone family seemed so much like one flesh, one nervous system” (ibid., 81).

11. “Strindberg and Our Theatre,” program note for a 1924 production of Strindberg’s The Spook Sonata (now usually translated as The Ghost Sonata), in Eugene O’Neill: Comments on the Drama and the Theater: A Source Book, ed. Ulrich Halfmann (Tübingen: Gunter Narr, 1987), 31–32.

12. Murphy, O’Neill, 32, 55, 81.

13. Ibid., 36, 53, 65. Carla Power, review of Long Day’s Journey, Newsweek, December 6, 2000.

14. Geraldine Fitzgerald, who played the part in 1971, noted: “Mary gets what’s called the ‘cat reaction’ to the drug. She gets more and more excited, not depressed, and I use that. And I thought about how easily she uses the needle, another key to her toughness.” Quoted in Murphy, O’Neill, 66.

15. Geraldine Fitzgerald commented: “If Mary Tyrone had never had a drug in her life, she would have been more or less the same! She is what she is because of her sense of guilt. She feels deeply guilty about her relationship with her mother, whom she didn’t like, and about her father, whom she adored but who died young. Many of O’Neill’s characters are based on ancient prototypes, and Mary Tyrone was a kind of Electra. Her behavior is based on the fact that she was a person who felt she was going to be given the worst of punishments for her own crime of cutting out her mother with her father.” Quoted in Virginia Floyd, The Plays of Eugene O’Neill: A New Assessment (New York: Frederick Ungar, 1987), 539–540.

16. The dynamic of a family with addiction at its core, as well as other psychological aspects, is analyzed by Walter A. Davis in Get the Guests: Psychoanalysis, Modern American Drama, and the Audience (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994), with a chapter devoted to Long Day’s Journey and another to The Iceman Cometh. See also Gloria Dibble Pond, “A Family Disease,” Eugene O’Neill Newsletter 9:1 (1985). For a discussion of O’Neill as alcoholic, see Tom Dardis, The Thirsty Muse: Alcohol and the American Writer (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1989), 211–256. Steven F. Bloom applies the discourse of alcoholism and codependency to Long Day’s Journey in “Empty Bottles, Empty Dreams: O’Neill’s Use of Drinking and Alcoholism in Long Day’s Journey Into Night,” Critical Essays on Eugene O’Neill, ed. James J. Mar-tine (Boston: Hall, 1984), 159–177.

17. See Laurin Porter, “‘Why Do I Feel so Lonely?’: Literary Allusions and Gendered Space in Long Day’s Journey into Night,” Eugene O’Neill Review 30 (2008): 37–47.

18. Murphy, O’Neill, 97.

19. Geraldine Meaney, “Long Day’s Journey into Night: Modernism, Post-Modernism, and Maternal Loss,” Irish University Review 21 (1991): 218, reprinted in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night: Modern Critical Interpretations, ed. Harold Bloom, 2nd ed. (New York: Chelsea House, 2009). Meaney uses Alice A. Jardine’s Gynesis: Configurations of Woman and Modernity, which in turn uses Luce Irigaray’s Speculum of the Other Woman to argue that Mary transgresses a limit imposed on women in patriarchy, namely (quoting Irigaray) “that prohibition that enjoins women . . . from ever imagining, fancying, re-presenting, symbolizing, etc. . . . her own relation of beginning. The ‘fact of castration’ has to be understood as a definitive prohibition against establishing one’s own economy of the desire for origin. Hence the hole, the lack, the fault, the ‘castration’ that greets the little girl as she enters as a subject into representative systems” (212). Meaney comments: “In establishing her own ‘mad’ relation to origin, Mary Tyrone denies her men the possibility of any sense of home. . . . They seek from her the consolatory denial of the fictionality of their identities. She punishes them with the truth” (ibid.).

20. Judith E. Barlow, “O’Neill’s Female Characters,” in The Cambridge Companion to Eugene O’Neill, ed. Michael Manheim (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 164, 172, 173. A literal recuperation of Mary’s character can be found in Ann Harson’s play Miles to Babylon, which depicts Ella O’Neill’s final recovery from addiction in a convent in 1913. Harson, Miles to Babylon: A Play in Two Acts ( Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2010).

21. A recent discussion of this way of looking at Jamie can be found in Robert M. Dowling, “Eugene O’Neill’s Exorcism: The Lost Prequel to Long Day’s Journey Into Night,” Eugene O’Neill Review 34 (2013): 9–10.

22. Jamie died in 1923, at the age of forty-five. After the death of his father in 1920, he lived a more stable and sober life with his mother, Ella. They were together in California in 1922 when she unexpectedly died. Jamie made the train journey back east, with Ella’s body in the baggage car, in the company of a prostitute and drinking heavily. O’Neill relates this story in A Moon for the Misbegotten, but the play omits the details of how Jamie, cynical about his brother’s growing fame and angry over efforts to manage the estate, publicly insulted Eugene’s wife as a prostitute. See the Gelb or Sheaffer biography for more details on these episodes.

23. Murphy, O’Neill, 39.

24. Virginia Floyd comments: “As a self-portrait, Edmund wears no mask, presumably because the author sees himself as a fully integrated person, more acted upon than acting. He provides precious few insights into his own nature. He alone is not stripped naked to the core of his soul.” Plays of Eugene O’Neill, 536.

25. Travis Bogard, Contour in Time: The Plays of Eugene O’Neill (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972), 435.

26. Murphy, O’Neill, 71, 86.

27. Ibid., 103.

28. To his son Eugene, Jr., O’Neill wrote in 1945: “My family’s quarrels and tragedy were within. To the outer world we maintained an indomitably united front and lied and lied for each other. A typical pure Irish family. The same loyalty occurs, of course, in all kinds of families, but there is, I think, among Irish still close to, or born in Ireland, a strange mixture of fight and hate and forgive, a clannish pride before the world, that is peculiarly its own.” Travis Bogard and Jackson R. Bryer, ed., Selected Letters of Eugene O’Neill (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 569.

29. Quoted in Edwin J. McDonough, Quintero Directs O’Neill (Chicago: A Cappella, 1991), 50–51. O’Neill’s diagrams were not published until 1981 in Virginia Floyd’s Eugene O’Neill at Work: Newly Released Ideas for Plays (New York: Frederick Ungar, 1981).

30. Quintero includes a valuable account of his discussions with David Hays and the other designers in If You Don’t Dance They Beat You, including his idea that there must be a rocking chair among the furniture: “A rocker is a woman, it’s a mother, rocking back and forth until you have fallen peacefully and completely asleep against her belly, your little arm gently resting on her breast. How deeply Florence [Eldridge] will have to suffer in that rocking chair. They will turn it into a witness box and lock her in it every once in a while. They will watch her, first out of the corner of their eyes, and then the trial will begin. First, it will be covered up with jokes and compliments and light conversation which ought to tremble in the air. They don’t want to believe she’s guilty. They are praying that she is not guilty, but they have to make sure she is not found guilty again. Give her time and she herself will give herself away. She knows that they know. She knows that by making the tiniest incorrect movement, they will know that she’s been driven to sinning again.” Hearing this, Eldridge spoke: “Yes, David, I must have a rocking chair” (220).

31. “Tragic Journey,” New York Times, November 9, 1956.

32. I interviewed Santo Loquasto on the telephone on January 13, 2013. I am grateful to him for giving perspective on his design process and for sharing pictures of his work.

33. Brian Dennehy recounts some of his long history with O’Neill’s plays in the online journal Drunken Boat in an issue (no. 12) devoted to O’Neill’s relation to Irishness. Dennehy speaks of the need to return again and again to the project of realizing O’Neill’s characters in a video clip on that website: www.drunkenboat.com/db12/04one/dennehy/dennehy3.php.

34. Teresa Wright fondly remembered Loquasto’s Hartford set and other aspects of the production in Yvonne Shafer, Performing O’Neill: Conversations with Actors and Directors (New York: St. Martin’s, 2000), 201–203.