Introduction:

What is Curry?

No source of influence in cookery . . . has exceeded imperialism. . . . The tides of empire run in two directions: first, the flow outward from an imperial center creates metropolitan diversity and ‘frontier’ cultures – cuisines of miscegenation – at the edges of empires. Then the ebb of imperial retreat carries home colonists with exotically acclimatized palates and releases the forces of counter-colonization, dappling the former imperial heartlands with enclaves of sometimes subject peoples, who carry their cuisine with them.

Felipe Fernández-Armesto, Near a Thousand Tables: A History of Food (New York, 2002)

If any dish deserves to be called global, it is curry. From Newfoundland to the Antarctic, from Beijing to Warsaw,1 there is scarcely a place where curries are not enjoyed.

But what is a curry? The definition of the word is elusive and controversial. In this book, we define curry the following way: a curry is a spiced meat, fish or vegetable stew served with rice, bread, cornmeal or another starch. The spices may be freshly prepared as a powder or a spice paste or purchased as a ready-made mixture.

The extensive use of spices is the most characteristic feature of Indian cuisine.

This very broad definition is an umbrella for many dishes: the classic Anglo-Indian curries of the Raj; the elegant gaengs of Thailand; the exuberant curries of the Caribbean; kari raisu, Japan’s favourite comfort food; Indonesian gulais; Malaysia’s delicious Nonya cuisine; South African bunny chow and bobotie; Mauritian vindaille; and Singapore’s fiery street foods. The story of these and other dishes will be told in the following chapters.

A secondary definition of curry is any dish, wet or dry, flavoured with curry powder – a ready-made mixture that generally includes turmeric, cumin seed, coriander seed, chillies and fenugreek2 (and may or may not include curry leaf, Murraya koenigii, a fragrant leaf widely used in southern Indian cooking). This category encompasses such diverse, hybrid dishes as German currywurst, Singapore noodles, Dutch fries with curry ketchup and American curried chicken salad.

Although there are many fanciful – and sometimes hilarious – explanations of the origin of the word ‘curry’,3 it probably derives from southern Indian languages, where karil or kari denoted a spiced dish of sautéed vegetables and meat. In the early seventeenth century, the Portuguese used the word caril or caree to describe broths ‘made with Butter, the pulp of Indian nuts . . . and all sorts of spices, particularly Cardamoms and Ginger . . . besides herbs, fruits and a thousand other condiments . . . poured in good quantity . . . upon boiled Rice’.4 In English, caril became curry, which Hobson-Jobson, the great dictionary of nineteenth-century British–Indian English, describes as ‘meat, fish, fruit or vegetables, cooked with a quantity of bruised spices and turmeric, and a little of this give a flavour to a large mess of rice’.

One of the traditional ways of grinding spices is in a mortar and pestle.

Curry leaves are used in many Indian dishes, although they are not a component of all curry powders.

Traditionally, the word ‘curry’ was not used by Indians, who called dishes by their specific names: korma, rogan josh, molee, vindaloo, doh piaza, etc. But today Indians often use the word for any home-made dish with a gravy, especially when talking with non-Indians. Even the celebrated Indian cookbook writer Madhur Jaffrey, who in 1974 wrote that the word ‘curry’ was ‘as degrading to India’s great cuisine as the term “chop suey” was to China’s’, called a later book The Ultimate Curry Bible (2003) – an indication of how the word has gained widespread currency.

Purists would insist that the only dish that deserves to be called curry is the one developed in the kitchens of British India in the late eighteenth century. This classic Anglo-Indian curry, which reached its apogee in the recipes of Colonel Kenney-Herbert (Wyvern), is made by sautéing onions in oil, adding pieces of meat or fish, and simmering it in water, stock, tomatoes or coconut milk. Spices – either freshly ground or a commercial curry powder – are added during the sautéing process.

These curries were always served with rice and various condiments such as peanuts, sliced or grated coconut, Bombay duck (dried Bomelo fish), sliced cucumbers and tomatoes, pickles and fruit chutneys. Initially a dish of the British upper classes, it gradually filtered down to middle-class and then to working-class tables. Curry lunches were a popular way of entertaining people in the ’50s, ’60s and even as late as the 1970s.

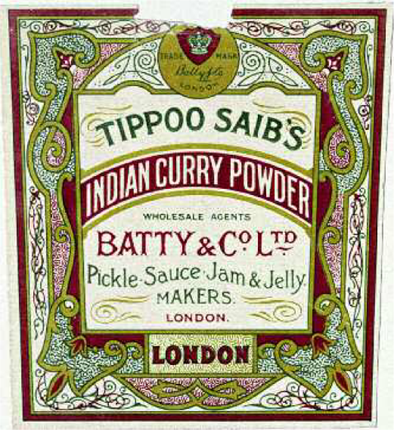

In the nineteenth century, a wide range of commercial curry powders made it easy for British housewives to prepare curries at home.

This style of curry was disseminated throughout the Empire by British cookbooks, immigrants and officials who, like modern executives, were transferred to different divisions of Great Britain, Inc. English-style curries became standard items in the taverns of nineteenth-century America, Canada, New Zealand and Australia (where a leading novelist once advocated making curry the national dish).

Curries and their cousins are an integral part of the cuisines of South-East Asia and Indonesia. As early as the third century BC, Indian traders and Buddhist missionaries brought tamarind, garlic, shallots, ginger, turmeric and pepper to the region. Starting from the eighth century AD, Arab traders introduced kabobs, biryanis, kormas and other meat dishes from others parts of the Islamic world, including the Middle East, Persia and India.

In the late fifteenth century, the Portuguese took over the spice trade and built a far-flung chain of trading posts in the Persian Gulf, the Malacca Straits, Indonesia, India and South Africa. In what is called the ‘Columbian exchange’, these settlements became the hub of a global exchange of fruits, vegetables, nuts and other plants between the western hemisphere, Africa, Oceania and the Indian subcontinent. One of the most important of these plants was the chilli pepper, which was rapidly assimilated into many local cuisines and became an essential element in curries.

In 2004 the British Foreign Secretary proclaimed chicken tikka masala a ‘true British national dish’ because it exemplifies the multiculturalism of British society.

In the seventeenth century, Portugal lost much of its empire to the British and the Dutch. The British Empire eventually came to encompass India, Ceylon, Burma, Malaya and Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, most of North America, Trinidad, Guyana, Fiji, Mauritius and many parts of Africa. The Dutch gained control over Indonesia, Ceylon, Surinam, the Antilles and South Africa. An important event in the history of curry is the abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire in 1807, followed by the abolition of slavery in 1833. To replace the freed slaves, the British brought in more than a million indentured labourers from the Indian subcontinent to work on plantations in the West Indies, South Africa, Malaysia, Mauritius, Sri Lanka and Fiji. The new arrivals integrated local ingredients into their eating habits to create new varieties of curries. A similar phenomenon occurred in the Dutch colonies.

But the traffic has not been all one way. Even under colonial rule, there was a trickle of people, ingredients and dishes from the colonies to the motherland, which became a flood after they gained their independence following World War Two.

In modern Britain, curry is on the menus of thousands of restaurants and curry houses and nearly as many pubs, some of which have special ‘curry nights’.

In The Hague, Amsterdam and other Dutch cities, many restaurants and shops sell Indonesian and Surinamese dishes and ingredients. Meanwhile, in New York and London, upmarket restaurants with Michelin stars serve sophisticated versions of curry using local ingredients, accompanied by elegant wines. Curry, the global dish par excellence, continues to evolve and adapt to changing times.