1

The Origins of Curry

First a sun, fierce and glaring, that scorches and bakes

Palankeens, perspiration and worry;

Mosquitoes, thugs, cocoa-nuts, Brahmins and snakes

With elephants, tigers and Curry.

Captain G. F. Atkinson, Curry & Rice: The Ingredients of

Social Life at ‘Our Station’ in India, 1859

No other part of the world has the ethnic, linguistic, cultural, religious, climatic or culinary diversity of the Indian subcontinent.1 The fertile plains of the Indus and Ganges rivers, the alluvial deltas of Bengal and the spice gardens of the Malabar Coast have yielded an agricultural bounty that was the foundation of a rich, varied cuisine. But most food is still produced and consumed regionally, and India has no national cuisine or national dish.

From prehistoric times, India’s geographic location has made it a magnet for migrations and invasions. The newcomers brought ingredients, dishes and cooking techniques, making Indian cuisine the fusion food par excellence. But the exchange was not one way. India exported its spices and dishes to the rest of the world, including mangos, sugar cane, tea, mulligatawny soup, kedgeree and the subject of this book, curry.

The Subcontinent and its Food

Archaeological evidence indicates that the earliest inhabitants of the subcontinent subsisted on a diet of rice, barley, lentils, pumpkins, aubergines, bananas, coconut, citrus fruits, jack-fruit and mangoes. They were the first people in the world to domesticate jungle fowl. Indigenous spices included turmeric, ginger, tamarind and long pepper (Piper longum).

Starting around 2000 BC, tribes of Indo-European pastoral semi-nomads migrated from the region between the Caspian and Black seas into northern India with their horses, cows, religion and languages. Their diet sounds far from appealing. Its staple was barley fried in butter, parched, ground into a meal mixed with yogurt, water or milk, or prepared as a gruel. Later they cultivated wheat, millet and rice. Dairy products, including yogurt and clarified butter, were widely consumed, as they are today. Their religious practices evolved into what is today called Hinduism and a caste system took shape.

The Indo-Europeans were not vegetarian and even ate beef. Around 500 BC two new religions emerged, Buddhism and Jainism, which preached non-violence and opposed the killing of animals for food. Vegetarianism became more common and austerity was associated with spirituality and high status. The tribes evolved into kingdoms and empires, and between 300 BC and AD 300, India was the wealthiest land in the world. Its merchants exported pepper, cardamom, silks and other luxury goods to the Roman Empire via Egypt. Caravans carried Indian goods over the Silk Road to the Persian Gulf, central Asia and China. Indian merchants sailed to South-East Asia, taking with them not only spices and textiles, but also Buddhism and Hinduism, art and dance forms, and Indian concepts of statecraft. The Chola dynasty based in Tamil Nadu was a major maritime power with outposts in Ceylon, Java, Borneo, Sumatra and the Malaya Peninsula.

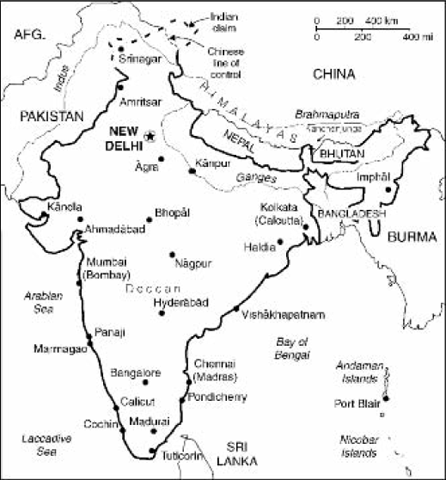

The Federal Republic of India consists of 29 states and 6 Union Territories. Some states are larger than most countries and have distinct languages, ethnicities, cultures and cuisines.

In the eighth century, Arab traders founded colonies on India’s west coast. Islamic warriors from central Asia began to invade north-west India, initially to plunder its wealth, later to stay and rule. By the mid-thirteenth century, the Gangetic Valley was part of an Islamic sultanate with its capital near modern Delhi. For more than three hundred years, much of India was ruled by various Turkish, Afghan and central Asian dynasties whose opulent courts attracted scholars and religious leaders from throughout the Islamic world.

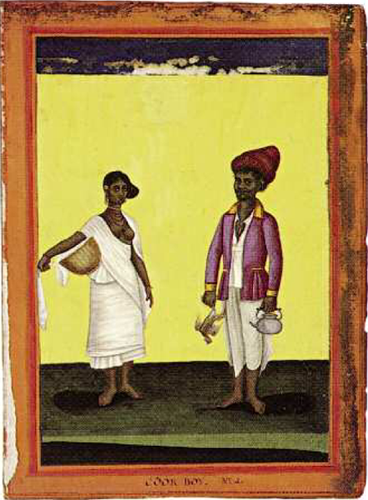

An Indian cook prepares kabobs and other dishes in the traditional style.

These immigrants brought ingredients and dishes that today are misleadingly called ‘Moghul’ – a word that should be removed from the Indian culinary lexicon! From Persia came rosewater and saffron; from Afghanistan and central Asia, almonds, pistachios, raisins and dried fruit; from the Middle East, sweet dishes and pastries. They introduced sherbets and other sweetened drinks; pulaos and biryanis, elaborate dishes of rice and cooked meat; samosa, a meat- or vegetable-filled pastry; dozens of varieties of grilled and roasted meats called kabobs; yakhni, a meat broth; dopiaza, meat slowly cooked with onions; korma, meat marinated in yogurt and simmered over a slow fire; khichri, a blend of rice and lentils; jalebi, coils of batter deep-fried and soaked in sugar syrup; and nans and other baked breads.2

In this imaginative painting, four Moghul emperors, including Babur on the far left, and their courtiers enjoy a feast in a garden pavilion. |

Many of these dishes have Persian names, which remained the language of culture in northern India until the nineteenth century. As one writer put it, ‘To the somewhat austere Hindu dining ambience, the Muslims brought a refined and courtly etiquette of both group and individual dining. The Muslims influenced both the style and substance of Indian food.’3 Meanwhile, the local cooks hired by the new rulers added their own spicing, creating a new Persian-Indian fusion cuisine.

In 1526 Babur, a descendant of the Mongol Genghis Khan, invaded northern India, defeated the ruler and proclaimed himself emperor of all Hindustan, thereby founding the Moghul dynasty (from the Persian word for Mongol). By 1700 the Moghuls had conquered the entire subcontinent except the very far south. In Europe, the word ‘Moghul’ was synonymous with fabulous power and wealth.

Abu’l Fazl ‘Allami (1551–1602), prime minister of the emperor Akbar (Babur’s grandson), has left a detailed record and description of the lavish kitchen at the royal court. He gives ingredients for 30 dishes that are still staples of north Indian cuisine. Although the lavish use of ghee (clarified butter) and spices such as cloves, cinnamon and cardamom epitomize the Moghuls’ love of luxury and high living, most of the dishes were the same as those introduced by earlier Islamic rulers. (Babur even hired several cooks that had worked for the previous ruler of Delhi.) The imperial generals and noblemen, called nabobs or nawabs, had their own courts in Lahore, Hyderabad and Oudh (Lucknow), where they developed local variations of the imperial cuisine.

For centuries Europeans had sought a sea route to the Indian subcontinent. Spices were a great luxury, valued not only for their taste and medicinal properties but also as a way of showing off wealth. Until the fifteenth century, the spice trade had been controlled by Arab traders, but this trade was interrupted by the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453. In 1498 the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama reached India’s Malabar Coast. The Portuguese established a fortress on the island of Goa, Europe’s first base on the Indian subcontinent (and the last to be relinquished, in 1961).

Goa was a key link in a chain of Portuguese forts and trading posts in the Persian Gulf, the Malacca Straits, Indonesia, India, Ceylon, Japan and South Africa. In what is called the ‘Columbian exchange’, the territories of the Portuguese and Spanish empires (Portugal united with Spain in 1580) became the hubs of a global exchange of fruits, vegetables, nuts and other plants between the western hemisphere, Africa, Oceania and the Indian subcontinent. The most important ingredient, and one essential to the story of curry, is the chilli pepper.

An 18th-century painting depicting a banquet at a royal court or aristocratic household.

Bombay was one of the three main ports of the East India Company.

On 31 December 1600 Queen Elizabeth I granted the East India Company, a group of English merchants, a monopoly of trade with the Indies. When the Dutch proved more powerful in the East Indies (Indonesia), the British turned their attention to India. The company built a chain of trading posts along both coasts and gradually extended their influence inland. In 1757 its troops defeated the Moghul forces and became the de facto rulers of large areas of India, although in theory they were subordinate to the British government.

In 1797 the British invaded Portuguese-ruled Goa, holding it for seventeen years before returning it to Portuguese rule. During this period, they discovered Goan cuisine, which combines classic Portuguese dishes, often made with beef and pork, with local ingredients. The most famous is vindaloo (from the Portuguese vinha e alhos, wine or wine vinegar and garlic) – a sour, fiery hot pork curry made with coconut vinegar, spices and red chillies. When the British left, they took these dishes and their Goan cooks with them.

By 1800 there were thousands of company administrators and military officers in India. They referred to themselves as ‘Indians’ or ‘Anglo-Indians’. British India was divided into three presidencies, headquartered in Madras (Chennai), Bombay (Mumbai) and Calcutta (Kolkata). However, in 1833 the company lost its Indian trade monopoly. A revolt in 1857 (called the Indian Mutiny by British historians, and the First War of Independence by Indian writers) led to the end of Moghul rule and the transfer of power to the British government. In 1877 Queen Victoria was named ‘Empress of India’ and India officially became known as ‘the Indian Empire’.

In the eighteenth century, English men in India enjoyed lives of considerable luxury. |

From this time until India gained its independence in 1947, around 60 per cent of its land area was under direct British rule. Both the territory and the administration are often referred to as the Raj. This territory included the three presidencies, the North-West Provinces, Punjab, Central Provinces, Oudh (Lucknow) and British Burma. The so-called native states, ruled by local rulers, were in effect subordinate to the British government.

Indian Foods and Cooking Techniques

Until the end of the eighteenth century, there was little sense of racial superiority among the British, whose main motivation was profit. Company men lived much like the native population: they spoke Indian languages; took Indian mistresses and wives (often called ‘sleeping dictionaries’); wore Indian clothes; and consumed Indian meals prepared by local cooks. Their heavy meat-centred meals featured spicy rice pulaos and biryanis, kabobs, kedgeree, chutneys, kormas, kalias and other Muslim dishes. The first British settlers may not have considered the highly spiced cuisine of India very strange, since in the early seventeenth century English cooking continued the tradition of the Middle Ages with its heavy use of cumin, caraway, ginger, pepper, cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg.

Then, as now, the food of the subcontinent was extremely diverse, reflecting regional, religious and social and caste differences, a discussion of which goes beyond the scope of this book. The basic techniques are deep frying, sautéing, boiling, braising and grilling. The most common cooking receptacle is a deep pot, karahi in Hindi, with two handles and a flat or slightly concave bottom.

A common Indian cooking technique with no exact equivalent in the West is called in Hindi bhuna. Spices and a paste of garlic, onions, ginger and sometimes tomatoes are fried in a little oil until they soften. Pieces of meat, fish or vegetables are sautéed in this mixture. Small amounts of water, yogurt or other liquid are then added a little at a time. The amount of liquid added and the cooking time determines whether the dish will be wet or dry. This is the basic technique used in making the dishes called curries.

The most distinctive feature of Indian cuisine is the use of spices and other strong flavourings, including garlic, onion and chillies. Many reasons have been given for the use of spices – and most are mythical. Hot spices do not induce enough perspiration to cool people down. Nor do they mask the flavour of tainted meat, since those who eat such food would be likely to die, or at the very least become seriously ill. The latest theory, backed by scientific evidence, is that a taste for spices evolved because they contain powerful antibiotic chemicals that kill or suppress the bacteria and fungi that spoil foods. The antibiotic effects are even stronger when combined with onions and garlic.

The gastronomical purpose of spices is to add flavour, texture and body to a dish. For the poor, they liven up simple dishes at low cost. Spices can be added in different ways and at different stages of the cooking process. At the start of making a meat dish, whole spices are sautéed in ghee or oil to release their essential oils. Whole spices may be boiled with water, vegetables or meat and bones to make a stock. Spices may be ground into a wet paste with onions, garlic, ginger, yogurt, coconut milk, vinegar or some other liquid, sautéed and turned into gravy by the addition of liquid.

A traditional way of preparing a meal in an Indian household.

Spices may be ground into a powder and stored in airtight bottles for a couple of weeks. Often they are first dry roasted to bring out their aroma. In the process called tempering, whole or ground spices are sautéed in a little oil, sometimes with onions and garlic, and added to a dish when it has finished cooking to create additional bouquet.

In Hindi, a spice mixture is called a masala. Its ingredients depend on many factors, including regional preferences, religion and the other components of a dish. The use of cumin, coriander and chillies is nearly universal throughout the subcontinent. Hindus commonly add a pinch of turmeric to dals and vegetable dishes to impart flavour and colour. In Bengal, the basic spice mixture consists of cumin, black mustard seeds, nigella, fennel and fenugreek. Southern Indian vegetarian dishes are typically flavoured with coriander, cumin seeds, black pepper, mustard seeds, fenugreek, asafetida (a substitute for garlic among orthodox Hindus) and curry leaf. In north Indian cookery, a mixture called garam masala, or ‘warm seasoning’, made from cinnamon, cloves, cardamom and black pepper (but rarely turmeric) lends fragrance and aroma to meat dishes and is associated with Muslim cuisine.

The Rise of Curry . . .

By the late eighteenth century, the word ‘curry’ was in general use among the British. In his classic Indian Domestic Economy and Receipt Book (first published in 1841), Dr Robert Flower Riddell (b. 1798), the superintending army surgeon at the court of the Nizam of Hyderabad, describes curries in the following way:

Curries consist in the meat, fish, or vegetables being first dressed [sautéed] until tender, to which are added ground spices, chillies, and salt to both the meat and gravy in certain proportions; which are served up dry or in the gravy; in fact, a curry may be made of almost any thing, its principal quality depending upon the spices being duly proportioned as to flavour and the degree of warmth to be given by the chillies and the ginger. The meat may be fried in butter, ghee, oil or fat, to which is added gravy, tyre [yogurt], milk, the juice of the coconut, or vegetables, etc.

Dr Riddell’s recipes are for dishes made at the Nizam’s court, including many for curry-like dishes called salan, a meat or vegetable dish with a thinnish gravy. He gives four recipes for curry powder which call for the same ingredients in different proportions: coriander seeds (roasted), turmeric (pounded), cumin seeds (dried and ground), fenugreek, mustard seed, dried ginger, black pepper, dried chillies, poppy seed, garlic, cardamom and cinnamon. A tablespoon of this mixture is recommended for a chicken curry together with six to twelve dried or green chillies(!) and one to three cloves of garlic. Tamarind, lime juice or mangoes, coconut milk or yogurt, and ginger can also be added.

A painting of nineteenth-century Indian cooks.

Another even more influential book published several decades later was Culinary Jottings for Madras (1878) written by Colonel Arthur Robert Kenney-Herbert (1840–1916) under the pen name Wyvern. Arriving in India in 1859 as a nineteen-year-old cadet, he was introduced to curries by a kind-hearted veteran, the last of a generation ‘that fostered the art of curry-making and bestowed as much attention to it as we . . . do to copying the culinary triumphs of the lively Gauls’. This veteran held tiffin parties at which he would serve eight or nine curries accompanied by fresh chutneys, grilled ham, fish roe and other condiments. Guests were expected to taste each curry, discuss its merits and ask for second helpings of the ones they especially liked.

Kenney-Herbert, who was a great admirer and proponent of French cuisine, believed that a curry deserved the same care and attention as a classic French fricassée or blanquette. His elaborate and painstaking recipe for chicken curry remains a classic (but would strain the resources and skill of most modern cooks). He recommends that the curry powder be made at home in large batches and stored in tightly sealed glass bottles, and scorns people’s lazy habit of allowing their cooks to make their ‘curry stuff ’ on the spot as needed. But he does not oppose the use of ready-made curry powder and recommends Barrie’s Madras Curry Powder and Paste (while warning against the curry powder sold by London grocers that is diluted with cornstarch and other contaminants).

His recipe (given on pp. 120–21) calls for the addition of small amounts of powdered cloves, mace, cinnamon, nutmeg, cardamom and allspice as well as ‘judicious amounts’ of green leaves of fennel, fenugreek, lemon grass, coriander and so on, or a paste of green ginger. An important element is a hint of sweet acid from tamarind and jaggery (unrefined brown sugar from palm sap). In England, acceptable substitutes are redcurrant jelly or chutney with a little vinegar or lime juice, or chopped apple and sour mango.

. . . and its Decline

By the middle of the nineteenth century, attitudes were starting to change, especially after the abolition of the East India Company in 1857 and the creation of the Imperial (later Indian) Civil Service in 1886. Britain continued to consolidate its territory possessions in India and with this came greater insulation from the people they ruled. The wearing of Indian clothes by Englishmen was banned, and the new public-school-educated officials looked down on the old company men who had ‘gone native’.

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 made it easier and faster to ship goods and people to India. Indian wives and mistresses were replaced by British wives, many of whom had little formal or domestic education and were ill equipped to manage the small army of domestic servants that was standard. They avoided Indian cuisine in order to distance themselves from those they governed and to distinguish themselves from the old company men. Curries ‘lost caste’, as Kenney-Herbert put it, and were banished from fashionable tables, although they continued to be served in army mess halls, clubs and the homes of ordinary British civilians, especially at lunch.

Entertaining was an important part of social and professional life among British officials. At formal dinner parties guests were served ‘tinned salmon, red-herrings, cheese, smoked sprats, raspberry jam, and dried fruits; these articles coming from Europe, and being sometimes very difficult to procure, are prized accordingly’.4 Dishes with fancy French names became de rigueur.

To help the memsahibs cope with their new environment, old Indian hands wrote domestic handbooks with menus and recipes, most of them for British and European dishes. Recipes for Indian dishes were relegated to separate chapters and often referred to in derogatory terms. Flora Annie Steel, author of one of the most famous handbooks, writes that ‘most native recipes are inordinately greasy and sweet’. The author of The Indian Cookery Book published in 1880 in Calcutta calls pellows (pulaos) ‘purely Hindoostanee dishes’, some of which are ‘so entirely of an Asiatic character and taste that no European will ever be persuaded to partake of them’. Of korma, the author writes that it is ‘one of the richest of Hindoostanee curries . . . but quite unsuited to European taste’.

The definition of what constituted a curry became more narrowly defined. The list of curries given in a typical nineteenth-century cookbook first published in 1891 (A Thirty-Five Years Resident, The Indian Cookery Book: A Practical Handbook to the Kitchen in India adapted to the Three Presidencies, Calcutta) is strikingly similar to the dishes on the menu of a twenty-first-century British curry house: doopiajas, gravy curries, kofta, hindostanee, hussanee, korma, malay, vindaloo, country captain, jhalfrezee, madras mulligatawny curry, chahkee, bhajees, dals and fish mooloos (molees). Some are not curries at all, but rather accompaniments to an Indian meal (see p. 33 for definitions).

Dinner parties featuring roasts and imported dishes were an essential feature of British social life during the Raj.

Vindaloo (from the Portuguese dish vinha de alhos, or wine vinegar and garlic) is a hot and sour Goan dish traditionally made with pork. It is a staple of English curry houses.

Some writers have classified curries by city or region, such as Bengal, Madras, Bombay and Ceylon. But, as Lizzie Collingham points out, ‘The Anglo-Indian understanding of regional differences was . . . rather blunt. They tended to hone in on distinctive but not necessarily ubiquitous, features of a region’s cookery and then steadfastly apply these characteristics to every curry that came under that heading.’5 Thus, all Ceylon curries were made with coconut milk, all Madras curries were hot, all kormas were made with yogurt, and so on.

The British had little familiarity with India’s many other regional cuisines: the delicate vegetarian dishes of Gujarat and Maharashtra, the complex seafood dishes of Kerala, the south India) or the pungent fish dishes of Bengal. There was a tendency to combine elements from different regions, by, for example, adding coconut milk, a standard ingredient in southern India, to north Indian Muslim dishes (equivalent, perhaps, to adding sesame oil to a coq au vin). Over time, curries became less authentic and more pan-Indian.

Bhajee [bhaji]: a dry sautéed vegetable dish

Bhoona: a dry but tender curry made by slowly adding liquid to a dish as it is stir-fried

Ceylon curry: a hot creamy curry made with coconut milk

Country captain chicken: a simple dish, usually made with chicken

Dhansak: a mild, sweet and sour Parsi dish made with meat, lentils, and vegetables

Do(h)piaza: a curry made with a large proportion of onions

Hindoostanee: a north Indian curry that includes aromatic spices

Hussaini: meat threaded on skewers and cooked in a gravy

Jalfrezi: a stir-fried dish made with pre-cooked meat, onions, tomatoes and green peppers

Kalia (qalia): an aromatic preparation of fish, meat or vegetables with a sauce based on ground ginger and onion paste

Kofta: a meatball curry

Korma (qorma, qoorma): a mild aromatic braised whitish meat curry, made with yogurt, cream or coconut milk

Madras: a hot curry

Malay curry: a rich dish usually made with coconut milk

Molee, moolee, Malay: a curry, often made with fish, cooked in a thin coconut gravy

Pasanda: a curry made with long strips of meat

Patia: a mild sweet and sour Parsi fish curry

Phall: an extremely hot curry

Rogan josh: an aromatic meat dish marinated in yogurt and coloured red

Salan: a meat or vegetable dish with a thinnish gravy

Tikka masala: small pieces of meat, usually chicken, in a spicy, reddish-coloured gravy

Vindaloo: originally a hot and sour Portuguese-Indian pork dish; today code for a very hot curry.

This homogenization was promoted by the constant movement of British officials. During their travels they stayed in dak (Hindi for post) bungalows – rest houses for travellers built every fifteen or twenty miles apart along main roads. The cooks would whip up a meal on the spot using whatever they could procure locally. One of the standards was country captain chicken, a dish that was to become very popular in the southern United States. See p. 121 for Dr Riddell’s recipe.

At the same time, some British dishes became Indianized. Meat casseroles made with carrots and celery in a wine-based sauce were made more interesting by a dash of curry powder. Indian cooks minced left-over meat, coated it in mashed potatoes, egg and breadcrumbs, and fried it to make ‘chops’ or ‘cutlets’. Indian-style omelettes, made with chillies and onions, are to this day a standard of Calcutta breakfasts.

A few Anglo-Indian hybrids became part and parcel of British cuisine. The breakfast dish kedgeree, a combination of rice, smoked fish, spices and hard-boiled eggs, is an elaboration of khichri, a simple mixture of boiled rice and lentils that is ubiquitous on the subcontinent. Another is mulliga-tawny soup, an adaption of southern Indian rasam, a thin broth of lentils, chillies and spices. The British added chicken, lamb or vegetables and thickened the liquid with flour and butter.

However, while curry ‘lost caste’ in India, the situation was very different in Britain, where all things Indian, from Kashmiri shawls and Indian jewellery to curry, became the fashion among a new cosmopolitan middle class. By the end of the nineteenth century, curry had become thoroughly integrated into middle-class British cuisine.