2

Britain

Me and me mum and me dad and me gran

We’re off to Waterloo,

Me and me mum and me dad and me gran

With a bucket of vindaloo.

Vindaloo, unofficial song of England

in the FIFA World Cup, 1998

One of the most remarkable developments in the history of gastronomy has been the emergence of curry as an archetypal British dish. It used to be axiomatic to equate British food with blandness, but ‘going out for a curry’, the hotter the better, has become a way of life for many urban Britons. More than eight thousand restaurants and curry houses and nearly as many pubs serve curry. Ready-made Indian meals are staples of supermarket and department stores, while packaged and frozen curries are sold throughout the British Isles. Curry has become the default take-away meal in the UK.

In 2001 a former foreign secretary, Robin Cook, proclaimed chicken tikka masala ‘a true British national dish, not only because it is the most popular but because it is a perfect illustration of the way Britain absorbs and adapts external influences’.1

Why do Brits have an ‘almost pathological affection’ for Indian food? As Cook observed, it is a reflection of the multicultural nature of Britain and the availability of Indian dishes and ingredients. Immigration grew rapidly after World War Two and the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947, and many immigrants opened catering firms, small shops, importing businesses and restaurants throughout the British Isles.

Perhaps this affection, consciously or subconsciously, reflects nostalgia for the Raj and the days when Britannia ruled the waves, a nostalgia encouraged by the popularity of the television mini-series Jewel in the Crown in 1984. Some British families had historical ties with the subcontinent dating back to the eighteenth century. Finally, curry may be a welcome relief from the blandness of traditional British food and part of a global trend to explore ‘hotter’ and more exotic cuisines.

The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

By the end of the eighteenth century, company men, known as ‘nawabs’ or ‘nabobs’ because of their wealth, began returning home. Many lived in or near London. The ‘Nabobery’ was first located near Regent’s Park and later in Bayswater and South Kensington. Just as the British tried to recreate their homeland while they were in India, now they tried to recapture something of their life in India after returning home.

Those who could afford it brought their cooks from India; others satisfied their appetite for curry at coffee houses. Curry was served in the Norris Street Coffee House at Hay-market in 1733. The first purely Indian restaurant was the Hindoostanee Coffee House which opened in 1809 at 34 George Street near Portman Square, Mayfair. (Before it was torn down, the building was marked by a plaque.) Its proprietor was an interesting character named Sake Deen Mahomed (1759–1851), an Indian who had served in the British army and married an Irishwoman. He tried to provide both an authentic ambience and dishes ‘allowed by the greatest epicures to be unequalled to any curries ever made in England’. However, the restaurant did not thrive and closed in 1833. One cause of its demise may have been the opening of the Oriental Club in 1824 in nearby Hanover Square as a meeting place for ex-company men. Its initial fare was French food; in 1839 it started serving curry. Today, the club continues the tradition by featuring a curry of the day on its menu.

William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1847–8) contains an amusing account of Becky Sharpe’s dinner with the Sedleys at which she tries to snare the wealthy nabob, Josiah Sedley, the collector of Boggley Wollah, by feigning a love of curry which she has never eaten, scorching her mouth in the process. Her surprise suggests that the dish remained relatively unknown outside Anglo-Indian circles in 1815 when the events of the novel took place.

William Thackeray’s Vanity Fair contains one of the first depictions of a wealthy India-returned ‘nawab’ in Josiah Sedley, depicted here with Becky Sharpe. |

The first British cookbook containing a curry recipe was Hannah Glasse’s Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1747). The recipe was essentially an aromatic stew flavoured with pepper-corns and coriander seeds but in the 1796 edition, curry and cayenne (chilli) powder were added. Curry recipes are found in Dr William Kitchiner’s The Cook’s Oracle (1816), Mrs Dalgairn’s Practice of Cookery (1829), Meg Dods’s The Cook and Housewife’s Manual (1826) and Maria Rundell’s Domestic Cookery. First published in 1807, this work went through 65 editions by 1841. The editions edited by Emma Roberts, who had lived in India, contained many recipes for curries and other Indian dishes, some attributed to the King of Oudh.

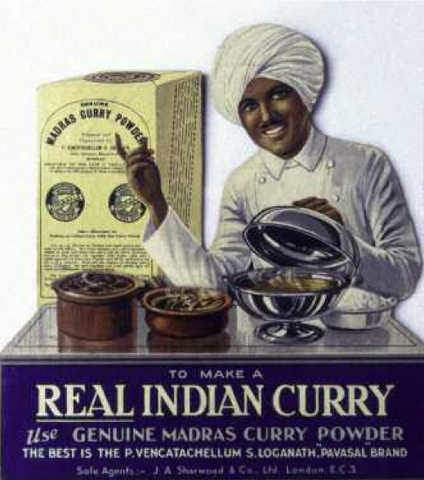

Enterprising merchants began manufacturing commercial versions and promoted their health and gastronomical benefits. In 1784 Sorlie’s Perfumery Warehouse advertised that curry ‘renders the Stomac active in Digestion – the blood naturally free in Circulation – the mind vigorous – and contributes most of any food to an increase in the Human Race’ (a hint at its alleged aphrodisiac powers). In 1844 Captain William White of the Bengal Army, manufacturer of Selim’s Curry Paste (sold until the late 1930s), published a pamphlet: ‘Curries: Their Properties and Healthful and Medicinal Qualities’. By the 1860s curry paste, mulligatawny paste and chutney were sold in large stores like Fortnum and Mason’s, Halls of London and Crosse and Blackwell’s shop in Soho Square. The most common ingredients in these powders were coriander seed, cumin seed, mustard seed, fenugreek, black pepper, chillies, turmeric and curry leaves and sometimes ginger, cinnamon, cloves and cardamom. Imports of turmeric tripled between 1820 and 1841. The basic mixture is similar to that used today in southern India as well as the blends described by Colonel Kenney-Herbert and Dr Riddell.

Curry was fashionable among the elite, including the Prince Regent’s set. But by the second half of the nineteenth century, curry had gained popularity among the urban middle classes, whose growing prosperity made them eager for new experiences. Indian fabrics, shawls, furnishings and food became fashionable. The memsahibs, who had once scorned Indian food at their own tables, now presented themselves as experts in Indian cuisine. Popular magazines printed recipes for curry and other Indian dishes. One reason for its popularity was economy: curry was an ideal way of using left-over meat and fish. In 1851 the anonymous author of Modern Domestic Cookery wrote: ‘Curry, which was formerly a dish almost exclusively for the table of those who had made a long residence in India, is now so completely naturalized that few dinners are thought complete unless one is on the table.’2

Curry became so popular that in 1845 the Duke of Norfolk, at the height of the Irish famine, told a group of labourers that they should put a ‘pinch of curry’ into hot water to assuage their hunger, since in India ‘a vast portion of the population use it; in fact, it is to them what potatoes are in Ireland’. This comment made the duke an object of considerable derision: The Times predicted ‘the noble cuisinnier [sic] will go down to posterity with a pinch of curry powder in his hand’, while the Yorkshire poet F. W. Moorman (1872–1919) referred to this speech in his poem The Hungry Forties:

There was a papist duke that com aleng

Wi’ currypowders, an’ he telled our boss

That when fowk’s bellies felt pination’s teng

For bread, yon taink’ powder they mun soss.3

James Allen Sharwood introduced his line of Indian chutneys, pickles and curry powders in London in 1889.

The two most influential Victorian cookbooks, Eliza Acton’s Modern Cookery in all its Branches (1845) and later editions of Isabella Beeton’s Household Management (first published in 1861), devote entire chapters to curry. Unlike Colonel Kenney-Herbert’s elaborate production, Mrs Beeton’s curry takes only 50 minutes to prepare. The onions are sautéed with, not before, the meat, together with minced apple (which became a standard sweetening/souring agent in British and North American curries). The curry powder is added at the same time as the stock. Flour is used as a thickening agent, and coconut milk is replaced by cream. Mrs Beeton recommends the curry powder ‘purchased at any respectable shop [as], generally, far superior and . . . more economical’ than those made at home.

Cookbooks exclusively dedicated to Indian food appeared. Richard Terry, chef at the Oriental Club in London, published Indian Cookery in 1861. Daniel Santiagoe, an Indian cook and former domestic servant, wrote The Curry Cook’s Assistant: Curries and How to Make them in England in the Original Style (1889, 3rd edn). In 1895 Henrietta Hervey, the wife of an Indian army officer (who brought her dekchies, or Indian pots, back with her from Bombay), published A Curry Book: Anglo-Indian Cookery at Home. Although she gives recipes for three curry powders – Madras, Bombay and Bengal – she is not opposed to the use of shop-bought mixtures.

Although Queen Victoria never visited India, she was fascinated by all things Indian. She collected Indian paintings and employed Indian servants dressed in exotic costumes, including two Indian cooks who prepared curry daily while she was at Osborne House. Her son Edward VII was a patron of the Savoy Hotel, which had a curry cook on the staff, and her grandson George V was said to have had little interest in any food except curry and Bombay duck.

Curry filtered down to the working classes where it enjoyed considerable popularity, because curry powders and curries were regarded as both economical and nutritious and because of its association with the Empire. Charles Elmé Francatelli, Queen Victoria’s personal chef, included a curry recipe in his book A Plain Cookery Book for the Working Classes (1861). In a poem by an anonymous author (actually Thackeray) that appeared in Punch’s Poetical Cookery-Book, the speaker, ‘Samiwel’, describes a domestic scene from working-class London:

Three pounds of veal my darling girl prepares

And chops it nicely into little squares

Five onions next prepares the little minx

The biggest are the best her Samiwel thinks

And Epping butter, nearly half a pound

And stews them in a pan until there brown’d

What’s next my dexterous little girl will do?

She pops the meat into the savory stew

With curry powder, tablespoonsfulls three

And milk a pint (the richest that may be)

And when the dish has stewed for half an hour

A lemon’s ready juice she’ll o’er it pour

Then, bless her, then she gives the luscious pot

A very gentle boil – and serves quite hot

P.S. Beef, mutton rabbit, if you wish

Lobsters, or prawns, or any kind of fish

Are fit to make A CURRY. ’Tis when done

A dish for emperors to feed upon.4

The Twentieth Century

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Britain was home to a few thousand Indians, mainly servants, students and ex-seamen from Bengal. Many came from the Sylhet region (now part of Bangladesh), which traditionally supplied cooks to the Portuguese and later the British. By 1920 there were a handful of Indian restaurants in London, including the Salut e Hind in Holborn, the Coronation Hotel and Restaurant, and cafés near the docks in the East End. One of the earliest restaurants to be called a curry house was the Shafi. Its employees were mainly ex-seamen, who later went on to start their own restaurants.

The first upmarket Indian restaurant was Veeraswamy’s at 99 Regent Street in London, today one of the capital’s finest Indian restaurants. It was opened in 1927 by Edward Palmer, a great-grandson of a Hyderabadi princess and an English lieutenant general. He was also the founder of E. P. Veeraswamy & Co., Indian Food Specialists, which imported spices and curry pastes from India and sold them under the label Nizam’s. Palmer had run the Indian restaurant at the British Empire Exhibition of 1924 at Wembley; it was so successful that he decided to make it permanent.5

An early menu from Veeraswamy’s, London’s first upmarket Indian restaurant. It opened in 1927 and became a popular dining place for royalty and celebrities. |

Palmer’s restaurant retained the Raj atmosphere of the exhibition café, with cane chairs, potted palms and Indian waiters wearing traditional bearers’ uniforms. The menu listed vindaloos, Madras curries, dopiazas, coloured pilaus and other popular Anglo-Indian dishes; the less adventurous could dine on English rump steak and lamb cutlet. Famous clients included the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII), King Gustav of Sweden, Charlie Chaplin and the King of Denmark. The restaurant was sold to the MP Charles Stewart and in 1997 purchased by Camellia and Namita Panjabi, who renovated it and restored its former cachet.

One of the by-products of Veeraswamy’s was the publication of a delightful little cookbook, Indian Cookery, ostensibly by E. P. Veeraswamy himself, who tells his (fictional) life story in the preface. First published in London in 1936, the book has been reprinted dozens of times. His instructions distil the essence of Anglo-Indian curry-making:

• Onions should be thinly sliced and never be allowed to brown

• Curry powder or spices should be lightly fried for a few minutes to get rid of their raw flavour

• Ready made curry powder is perfectly acceptable since every ingredient in a genuine curry powder is identical to what is ground on the curry stone in Indian households.

• Those who speak of ‘fresh ingredients’ being used in India know absolutely nothing beyond what their native Indian servant has told them.

• Any kind of fat can be used

• Milk or sour cream can substitute for coconut milk in many curries

• On no account thicken curry with flour. If the gravy is too thin, add coconut milk, milk or dried coconut and/ or evaporate with the lid off

• Apples and raisins are never used in Indian curries

• Curries should be served in separate dishes, never with rice as a border

• Curries should be eaten with a dessert spoon and fork

• Proper accompaniments include pappadums, chutneys, pickles, Bombay duck and sambals.6

After 1947 many immigrants found employment in the restaurant and catering businesses and opened hundreds of small restaurants of their own. Their customers were initially other South Asians as well as British men who had lived in India or were stationed there during the War. Their menus featured dishes found in the cookbooks and on the tables of the Raj.

Companies such as Noons, Pathaks (later Pataks) and S&A foods began to manufacture Indian spice mixtures and sauces, chutneys, pickles and other Indian products. In the 1960s the emergence of the counter-culture and the Beatles’ visit to India contributed to the growing popularity of Indian food, as did Madhur Jaffrey’s books and television cooking series in the 1970s.

The creation of Bangladesh in 1971 generated a new wave of immigrants who found employment in ‘curry houses’, the generic name for a generally downmarket Indian or Pakistani eating establishment. The curry house decor traditionally featured red flock wallpaper (perhaps an attempt to replicate the environment of Raj-era clubs). Most of the customers turned up just after 11 p.m., the closing time for pubs. ‘Going out for a curry’ after a night of hard drinking at weekends became a way of life for a certain segment of the population. Often the curries were prepared with ready-made sauces, giving the food a certain homogeneity. In his book, The Curry Bible, Pat Chapman lists the following sixteen curries as most popular in British Indian restaurants: balti, bhoona, dhansak, jalfrezi, keema, kofta, korma, madras, masala, medium, pasanda, patia, phall, roghan josh, tikka masala curry and vindaloo – a list not very different from those given in the Indian Cookery Book published in 1880.

How ‘authentic’ were their menus? The typical Indian restaurant menu throughout the world is largely an artificial creation. In Indian households, meals do not normally have a sequence of courses. The dishes arrive more or less at once and remain on the table throughout the meal. Most of the calories come from starch, either rice or bread, and dal (boiled lentils), supplemented by small amounts of meat, fish and vegetables, pickles, chutneys, salads and yogurt. The Western concept of a main course, usually meat, is alien to India, as are hors d’oeuvres and desserts.

To appeal to non-Indian customers, restaurant owners adapted Indian dishes to a Western format. As appetizers, they served street foods and snacks such as samosas, pakoras, kabobs and baskets of papads or pappadum, crunchy flat discs made from lentil flour and served with coriander and tamarind sauces. Dal was sometimes served as a soup, not as a core element of a meal. Sweets, normally eaten at festivals or as an afternoon snack, became desserts.

In the 1970s tandoori restaurants became popular (although the first tandoor, a clay oven, had been imported in 1959 by Veeraswamy’s). All these establishments were essentially imitators of Moti Mahal restaurant opened in New Delhi in 1948 by Kundan Lal Gujral. A refugee from Pakistan, Kundan Lal invented tandoori chicken: pieces of chicken marinated in yogurt and spices and roasted in a tandoor, which he had built to order. To please richer palates (and, some claim, use left-over tandoori chicken), he created butter chicken – pieces of roasted chicken served in a tomato, cream and butter sauce – the precursor of chicken tikka masala. Nans and other breads and kabobs cooked on long skewers in the tandoor were featured on the menu. Moti Mahal was one of the very first restaurants in India serving Indian food that attracted a middle-class clientele.

Balti dishes are prepared and served in wok-like pots called karahis or karhais.

The next sensation was balti cuisine, which started in south Birmingham in an area now called ‘the balti triangle’ and spread to other cities. Its origins are unclear. Some claim it originated in Baltistan, a province high in the Pakistan Himalayas, although the food there bears no resemblance to balti cuisine. Another explanation is that the word ‘balti’ means bucket in Hindi, perhaps a reference to the wok-like pot called a karahi or karhai. A similar dish is served in North America as karahi gosht, or frontier chicken (a reference to the North- West Frontier province).

To make a balti, pieces of marinated – usually precooked – meat, vegetables or seafood are stir-fried and served in a sauce of puréed onions, ginger, garlic, tomatoes, ground spices and fresh coriander. Aubergine, potato, mushrooms, corn, lentils and other ingredients may be added. A balti is cooked and served in the same pot and scooped up with pieces of baked bread. Side dishes and starters include fried onions, samosas, chutneys and pappadums. Often, patrons may bring their own alcoholic drinks. The popularity of the balti is easy to understand: it is delicious, easy to make, cheap and lets patrons create their own dishes and share them with others.

Balti and tandoori dishes were added to the menus of curry houses. The cooks adapted the ‘hotness’ of a dish to the diner’s taste, and it became a sign of manliness to eat a very hot curry, washed down by prodigious amounts of beer. Vindaloos were hot, but the hottest of all, for reasons unknown, were called phal, which means ‘fruit’ in Hindi. These macho connotations led to the adoption of the song ‘Vindaloo’ as an unofficial anthem for English football fans during the 1998 World Cup.

Eating curry, the hotter the better, has become a feature of British pub and restaurant life.

In the 1960s and ’70s curry recipes were popularized in cookbooks and magazines. Harvey Day’s Curries of India, which contains recipes for all the familiar Anglo-Indian dishes, became a bestseller. Pat Chapman, founder of the Curry Club in 1982, has done the most to promote curry. His many books and publications give recipes for dishes found in UK curry houses and balti restaurants, making them accessible to non-Indians who want to make them at home.

To ‘purists’ who claim that the British public is being duped by restaurateurs serving inauthentic dishes, Chapman replies that commercial exigencies and the need for rapid service forces restaurants to adapt techniques and ingredients different from those used in home cooking, and that ‘formula’ restaurant-style curries can in any case be superb. Since 1984 Cobra Beer has sponsored a guide to the hundred best curry restaurants and balti houses in Britain based on reports from Curry Club members.

In 1982 Camellia Panjabi opened Bombay Brasserie in Kensington with the aim of celebrating regional cooking and challenging the downmarket perception of Indian restaurants. Other top-end venues include the Red Fort, which opened in Soho in 1984 to serve upmarket northern Indian Muslim and tandoori dishes; the Panjabi sisters’ Chutney Mary in Chelsea (1990), featuring dishes from six regions of India; Cyrus Todiwala’s Café Spice Namaste (1991), which offers Goan, Parsee and other regional specialties; Zaikia; Chor Bazaar; and Cinnamon Club.

The latest episode in the saga of British curry is the emergence of very expensive Indian restaurants in London. In 2008 five Indian restaurants were awarded a Michelin star: Amaya, Benares, Quilon, Rasoi Vineet Bhatia and Tamarind. With their elegant decor, extensive wine lists, immaculate service and focus on regional ingredients, they are a far cry from the curry houses of old. Benares’s Atul Kochhar (the first Indian chef to win a Michelin star) even represented London and the South-East in the BBC’S Great British Menu competitions – the ultimate proof of how deeply Indian food has become integrated into British life.