6

South-east Asia

Mussaman curry is like a lover

As peppery and fragrant as the cumin seed

Its exciting allure arouses

I am urged to seek its source

King Rama II of Thailand,

Boat Songs, 1768–18241

Overview

The countries of South-east Asia – Myanmar (previously Burma), Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Malaysia, Cambodia and the island nations of Singapore, Brunei, East Timor, Indonesia and the Philippines – are plural societies characterized by a dominant ethnic majority and many minorities. From ancient times, the region held a key position in the trade routes between India and China and was subject to their political, cultural and culinary influences. Starting in the fourth century BC Indian merchants brought not only spices and textiles, but also Hinduism and Buddhism (the main religions of modern Thailand and Cambodia), new forms of dance, sculpture and music, and Indian concepts of state-craft. So-called ‘Hinduized’ kingdoms flourished in what are now Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia and Indonesia until well into the eighteenth century.

These traders may also have introduced tamarind, garlic, shallots, ginger, turmeric and pepper to the region and disseminated herbs such as lemon grass and galangal (a ginger-like rhizome) from one area to another. The Chinese legacy includes such ingredients as soy sauce, tofu and bean sprouts and the technique of stir-frying.

In the eighth century, Arab traders took over the spice trade and converted many local people to Islam, today the dominant religion in Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei. They introduced kabobs, biryanis, kormas and other meat dishes from the Islamic world (including the Delhi sultanate). They also popularized the use of cloves, nutmegs and other local spices. In 1511 the Portuguese established a trading post at Malacca on the Malay Peninsula and introduced the chilli, which was quickly assimilated as a replacement for white peppercorns.

In 1602 the Dutch East India Company (VOC) founded Batavia (modern-day Jakarta). It became the capital of the Dutch East Indies, the predecessor of modern Indonesia. The British acquired Penang Island in 1786, established Singapore in 1819 and later extended their control over the Malay Peninsula and Burma. They built pepper, sugar, tea, palm, coffee and rubber plantations and imported labourers from southern India.

The Spanish took control of the Philippines in 1571 and converted most of the population to Catholicism. The French lost most of their colonies in Canada and India to Britain in 1815, but developed a second empire between 1830 and 1870 when they moved into North Africa and parts of South-east Asia. By 1914 the French empire encompassed Indochina (Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam), Tunisia, Morocco, parts of West Africa and Madagascar. Thailand, known until 1939 as Siam, was the only South-east Asian country that was never colonized.

Throughout South-east Asia, rice is the staple (in many languages ‘to eat’ is expressed as ‘to eat rice’), served with side dishes: grilled meat or fish; vegetables, soups and soup-like dishes; curry-like dishes with a thicker gravy; and condiments. The starting point for soups and curries is a paste of chillies, garlic, shallots or onions, galangal, aromatic leaves and herbs, and sometimes dried or whole spices. The paste (called bumbu in Indonesia, rempah in Malaysia) may include lemon grass, makrut (kaffir) lime leaves and zest, and basil leaves – ingredients rarely found in Indian cuisine. Aromatic spices (such as nutmeg, cloves and cinnamon) are used less frequently and then generally in meat-based dishes.

The spice pastes may be wet or dry, as simple as garlic, chillies and shallots or containing as many as twenty ingredients. They may be simmered with the curries or fried in oil or separated coconut milk. Coconut milk is the most common liquid; yogurt, a common thickener in Indian curries, is rarely used in the rest of Asia. Another standard ingredient is a cooked fish or shrimp paste (kapi in Thailand, blacang or belachan in Malaysia and Indonesia) and fish sauces, all made from fermented salted fish.

Thailand

Thailand has the most complex and sophisticated cuisine in South-east Asia. This reflects the continued presence of a royal court which encouraged the culinary arts, considerable regional diversity and a wide range of ingredients. The Theravada Buddhism practised by most Thais does not prohibit or even discourage the eating of meat except as a voluntary practice.

A traditional Thai meal includes rice, soup, salad, a steamed, fried, stir-fried or grilled dish, a spicy vegetable and fish dish, curry, condiments, dessert and fruit, served at the same time and in no particular order. Long-grain jasmine rice is preferred in southern and central Thailand, short-grain sticky rice in the north.

The Thai word for curry, gaeng (sometimes written kang, gang or geng), basically means ‘any wet savoury dish enriched and thickened by a paste’. The starting point is an aromatic curry paste, either made at home or purchased. The ingredients for a curry paste are pounded together in a stone mortar, which allows the release of the essential oils that impart flavour and aroma. Preparing curry pastes can take half an hour for a daily meal.

Galangal, sometimes called wild ginger, is a component of many curry pastes in South East Asia.

Most Thai curry pastes contain shrimp paste (kapi or gapi) made from tiny plankton shrimp that are marinated in salt, dried in the sun, pulverized and fermented for months. The paste may be roasted on a banana leaf before using. Kapi, chillies, lime juice, ginger, garlic and palm sugar are combined to make one of the most typical (and ancient) Thai relishes, nam prik.

In addition to the basic ingredients, some Thai curry pastes contain grachai (wild ginger, similar to galangal), which has a slightly pungent flavour and is often used for decoration; coriander root, which imparts a sweet freshness; and lemon, Thai and holy basil, each with their distinctive nuances. The ideal is to achieve a balance of hot, sour, salty and sweet flavours in both an individual dish and a meal. As Thai food expert David Thompson writes:

In a good Thai curry, each flavor should be tasted to its desired degree and no one flavor should overshadow another. The striving for a complex balance of ingredients is nowhere more apparent than in curries: robustly flavoured ingredients are melded and blended together into a harmonious, yet paradoxically subtle and cohesive whole.2

Curries are either water-based or coconut-milk-based. Coconut-milk-based curries are prevalent in Bangkok and central Thailand. Water-based curries are more common in northern Thailand on the border with Myanmar and Laos. These curries are hotter and sourer than in the rest of Thailand, because the dishes are not diluted with coconut milk or sugar. A popular dish is Gaeng Hung Lay, or Myanmar-style pork curry made with pickled garlic and black bean sauce. Noodles are eaten as lunch or a snack.

Thai curries are categorized by the colour of the paste used in their preparation. A red curry paste includes dried red chillies, peppercorns and lime zest, and sometimes roasted and ground ‘Indian’ spices such as coriander, cumin and cloves. This mixture is used with almost any kind of meat, fish or vegetable. Red curries have plenty of sauce which is salty sweet and can be quite ‘fiery hot’.

Yellow curry paste, popular in fish and seafood stews, contains turmeric, ready-made curry powder and roasted coriander and cumin seeds. It is also the base of an Indian-like chicken curry called geang garee made with onions and potatoes, ingredients rarely used in Thai cuisine.

Green curry paste, combined with strongly flavoured meat or fish or bitter vegetables, contains fresh green chillies, basil leaves, lime leaves and often round green aubergines.

Panang/Penang curry paste is made with dried red chillies, white pepper and sometimes peanuts and is often used with beef dishes. Massaman/Mussamun curry, a thick stew-like curry made with lamb or beef, originated near the Malaysian border where there is a large Muslim population. The paste contains dried red chillies, ground coriander, cumin and cloves, white pepper, peanuts and, unusual for a Thai curry, roasted whole spices such as cinnamon, cardamom and nutmeg.

Thai curries, like this green curry, are categorized by the colour of the paste and ingredients used in their preparation.

Thailand’s Neighbours

The French brought in labourers from their colonies in southern India to their possessions in the region that is now Vietnam. One consequence is the use of southern Indian-style curry powders, especially in the south. Popular dishes are chicken curry (cari ga) made with coconut milk, and beef curry (cari bo) that often contains bay leaves, cinnamon, onions, carrots and potatoes or sweet potatoes. Dietary staples are long-grain Indian rice prepared with coconut milk cashews, ginger and onion, French baguettes or noodles.

Cambodian cooks use curry pastes called kroeng based on lemon grass, galangal, wild ginger, garlic, shallot, lime zest and turmeric. Like Thai curry pastes, they come in red, yellow and green versions. A Cambodian dish served on festive occasions is samaran, a thick rich beef or duck curry made with cardamom, ginger and ground peanuts. Dishes of lightly stir-fried leafy green vegetables and pickled vegetables balance the stews. Laotian curries are hybrids, using a herbal base similar to that used in Thailand, sometimes with fresh dill.

Myanmar, part of British India until 1948, is made up of many ethnic groups, but the two greatest influences on its cuisine are India and China. In the 1940s half of Yangon’s (Rangoon’s) population was of Indian origin; today Indians account for only 2 per cent. The Indian influence is apparent in Myanmarese samosas, biryani, street-side snacks, breads and curries, which incorporate Indian spices and lemon grass, basil leaves and fish sauce. Curries made from freshwater fish are especially popular. The liquid can be fish stock, water or coconut milk.

A Thai Massaman curry is Muslim in origin and generally made with beef. The curry paste usually contains turmeric, cardamom, cinnamon, cumin, cloves and nutmeg. |

Chickpea flour, toasted rice, garlic, onions, lemon grass, banana heart, fish paste, fish sauce and catfish cooked in a broth are combined to make the national dish, a Chinese-Indian-Myanmarese hybrid called mohinga, which is sold by streetside vendors. It is served with rice noodles, lime, crisp fried onions, coriander, spring onions and dried chillies.

Indonesia

The republic of Indonesia is an enormous country of nearly 15,000 islands; a population of 238 million, two-thirds of whom live on the island of Java; and a wide variety of languages, cultures and culinary practices. Although nutmeg, mace and cloves put Indonesia on the world stage, they appear sparingly in the cuisine (although cloves are a main component of kretek, the local cigarette). The Dutch planted tomatoes, cabbage, cauliflower, carrots and other European vegetables in the highlands; the Indians brought cucumbers, aubergines and onions; and the Chinese introduced mustard greens, soybeans and soybean cakes.

Throughout Myanmar, street-side vendors like this one in Mandalay sell dishes of mohinga, a fish noodle soup eaten for breakfast.

According to Jennifer Brennan, there is really no haute cuisine in Indonesia.3 Unlike in Thailand, the nobility reserved their creativity for literature and the arts. In much of Indonesia, boiled white rice is the focal point of a meal, supplemented by a soup, sautéed vegetables or gado gado (a salad of blanched vegetables in a peanut dressing), crunchy crackers (krupuk) made of flour, perkedel, corn or potato fritters, sometimes fried rice, a meat or fish stew, and at least one or several chilli-based fiery relishes called sambals that are widespread in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, the southern Philippines, India and Sri Lanka.

Sambal goreng (literally ‘fried relish’) is a general term for an entire class of curry-like dishes made with meat, fish, seafood or vegetables. They may or may not contain coconut milk, and can be wet, dry or in between. In western Sumatra, a legacy of the ancient Indian and Arab traders is the use of such ‘Indian’ spices as coriander, cumin, turmeric and cinnamon. In Pedang, as well as the western and northern parts of the Malay Peninsula, a korma-like dish called rendang is popular. A traditional dish of West Sumatra, it probably arose from the need to preserve the meat from a newly killed buffalo as long as possible in the absence of refrigerators. A rendang is made by simmering pieces of beef or water buffalo in a gravy of coconut milk and a paste of garlic, chillies, ginger, turmeric and aromatic spices until it absorbs the liquid and turns nearly black.

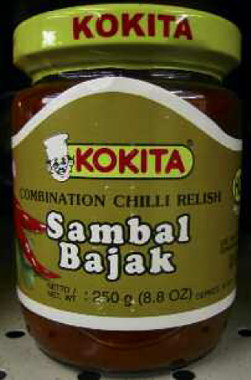

Sambal bajak is an extremely hot Indonesian relish made with fried red chillies, tamarind juice, shrimp paste and ground nuts. |

Nasi goreng is an Indonesian/Malaysian dish of fried rice prepared with egg, vegetables, shallots, soy sauce and chillies. It can be eaten by itself or served with meat or seafood.

The food of Java is more subtle, often combining sweet, sour and hot flavours. Main dishes include sotos, or soups; sayurs, thin stews with a preponderance of vegetables; and gulais, a word often translated as ‘curry’, made with a thick-ish coconut-milk gravy. Dutch-Indonesian hybrids include kari jawa, beef and potatoes cooked in coconut milk; semur, slices of beef served in a gravy made from sweet soy sauce, nutmeg and cloves, tamarind and palm sugar; and pergedels (from the Dutch frikkadels), deep-fried golden fritters made from seafood or vegetables. The Chinese influence is apparent in nasi goreng and batni goreng, fried rice or egg noodles with egg, vegetables, shallots, soy sauce and chillies, and served with fried chicken or shrimp, or a few sate sticks.

In some ways, the experience of the Dutch in the East Indies parallels that of the British in India. In the early days, employees of the Dutch East India Company, military officers and merchants often took wives and mistresses from the local population. These Javanese or Chinese women, called Nonya (sometimes written Nona or Nonna), were famous for their household management and culinary abilities. Cookbooks were written for them in Malay giving recipes for Dutch roasts, stew, waffles and pastries, Indian curries and Portuguese and Chinese dishes. (One of these authors, Nonna Cornelia, invented charming names for the women who contributed recipes: Mevrouw [Dutch for Mrs] Satay, Mama Cutlet, Ma-Kokkie Pork Chop, Nonna Fishy and Mevrouw Cucumber!) The first Dutch-language cookbook was published in Java in 1866.

Following the opening of the Suez Canal, more Dutch women came to the East Indies as wives. To help them adjust to their new lives, especially the entertaining required to maintain their husbands’ social positions, a spate of magazines, household guides and cookbooks were published both in the East Indies and the Netherlands. A special training school was even opened in The Hague in 1920.

Familiarity with local culture and cuisine was considered important for Dutch administrators and a hybrid Dutch-Indonesian cuisine emerged. Its most famous product was rijsttafel, which translates as rice table, a meal composed of many small dishes of meat, vegetable, fish and condiments served with plain and coloured rice. Far from being authentic, it was invented in the late nineteenth century by Dutch planters in East Java (perhaps in imitation of a traditional Javanese ceremonial meal) as a way of showing off their affluence. Forty, sixty or as many as eighty male waiters, dressed in starched white uniforms with batik cummerbunds, would serve the corresponding number of dishes on silver trays. Rijsttafel was served in colonial homes as Sunday lunch, at dinner parties or even as a precursor to a European main course. It was standard fare on ships heading from the Netherlands to the East Indies as one way of acclimatizing new recruits. Today Rijsttafel is served in tourist hotels in Indonesia, on cruise ships and, in a truncated version, in restaurants in the Netherlands and former colonies such as South Africa and the Dutch Antilles.

Malaysia and Singapore

The Malaysian federation covers much of the Malay Peninsula and the north coast of the island of Borneo, which it shares with Indonesia and the kingdom of Brunei. About two-thirds of its 25 million-strong population are Malay, 25 per cent Chinese and around 8 per cent Indian, predominantly Tamils. Singapore, which seceded from Malaysia in 1965, has a large Chinese majority and Malay and Indian minorities.

Some Chinese came as traders as early as the sixteenth century; others were imported by the British to work in the tin mines in the early nineteenth century. The Indian workers, mainly Tamils from southern India and Sri Lanka, came as indentured labourers to work on the rubber and palm plantations. Indian civil servants trained in India also settled in Malaysia and Singapore.

The cuisine reflects this cultural diversity. While the various communities have retained their distinctive dishes, they have also produced some delicious hybrids that make Malaysia and Singapore an eater’s paradise.

Malaysia has many dishes in common with Indonesia including satays, kormas, biryanis and gulais. In northern Malaysia, bordering on Thailand, the dishes and ingredients are closer to Thai cuisine. In the south-east, Javanese influences are apparent in the sour fish soups.

Many Chinese took Malay wives, called, as in Indonesia, Nonya or Nyonya, who developed the celebrated fusion cuisine called Nonya or Peranakan. It combines Chinese recipes and techniques with local ingredients such as coconut milk, galangal, candlenuts, pandanus leaves, tamarind juice, lemon grass, lime leaf and a strongly flavoured shrimp paste called cincaluk. No meal is complete without a sambal belachan, a side dish of fermented shrimp paste.

A well-known Nonya dish is curry chicken kapitan (no relation to country captain chicken; a kapitan was a prominent member of the community who served as an intermediary between the Chinese community and the Malaysian rulers). Pieces of chicken are sautéed in a spice paste containing anise, Indian spices, ginger, shrimp paste, garlic, shallots and chillies and simmered in a liquid of coconut milk, tamarind water and cinnamon stock and thickened with ground coconut.

Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and other Malaysian cities are famous for their street foods. The popular breakfast dish laksa, originally a Nonya recipe, is a fiery chilli-infused coconut milk broth containing noodles, belachan, prawns, lemon grass, shredded chicken, coriander and hard-boiled egg, always served with sambal and a slice of lime. A hot and sour asam laksa is made with tamarind juice and hot chillies; a milder laksa lemak uses coconut milk in the liquid. Another popular street food is fish-head curry, supposedly invented by two Indian cooks in Singapore in 1964. It incorporates southern Indian ingredients such as okra, aubergine, mustard seeds, fenugreek and curry leaves as well as the technique of ‘tempering’ – adding sautéed spices to a dish at the end of cooking.

Laksa, a fiery noodle and seafood soup served by street-side vendors in Singapore and Malaysia, is a product of the hybrid Malaysian-Chinese Nonya cuisine.

South Indian curries, together with idlis, dosas, vadas, sambars and rasams, are served in Singapore and Malaysia’s ‘banana leaf ’ restaurants. A local equivalent of an Indian stuffed roti is murtabak (from the Arabic word for folded). A dough made from white flour is wrapped around spiced minced meat and beaten egg and folded into packets that are sautéed, cut into pieces and served with a curry sauce.

Singapore noodles, a standard item on North American and European Chinese restaurants, is not Singaporean at all but probably a creation of Cantonese restaurants in Hong Kong. This mixture of rice noodles, shrimp, pork, chicken, onions, red peppers and other vegetables flavoured with curry powder is similar to a Singaporean/Malaysian vermicelli noodle dish called Xin Zhou Mee Fen that is traditionally flavoured with ketchup and a little chilli sauce.

Although not an integral part of Chinese cuisine, curry powder is added to a few dishes in South China. Most Chinese cookbooks in the West contain recipes for chicken curry and curry-flavoured noodles. The curry powder sold in Chinese grocery stores is similar to Madras curry powder with the addition of star anise and cinnamon.