THE OPPOSITE OF A CHICK MAGNET

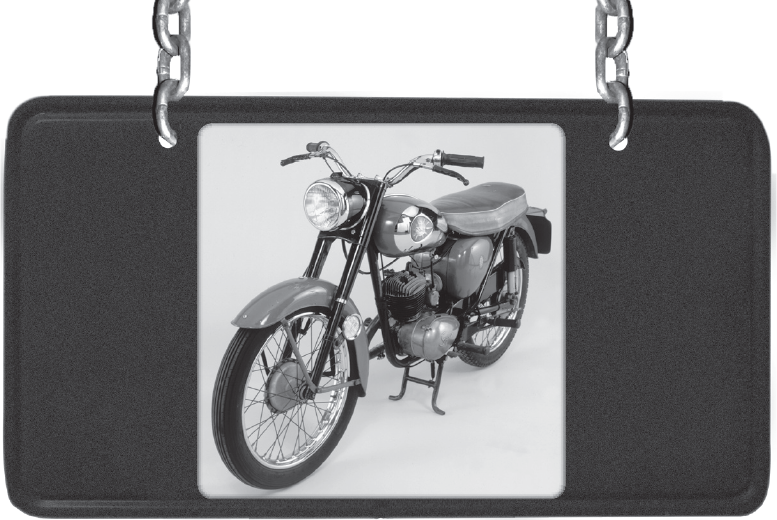

My very first means of motorized transport was an ex-army, khaki-colored BSA 125-cc Bantam. My father had bought it off a friend at work. It was almost brand-new. This friend had bought an ex-army Bedford three-ton truck at an auction. It had a canvas cover on the back. He took it home, and under the canvas were ten motorcycles, part of a job lot. So he sold them to workmates and it paid for the truck and then some.

Once again, my dad was thinking of me, not himself. The bike was a typical piece of British “why we nearly lost the war” lump of shite. I mean, what would you rather go to war in? A BMW or an Austin? A Mercedes or a Morris? Everything on this bike smacked of the First World War. The accelerator cable snapped at least once a week. The headlight bulbs popped at any speed over 35 mph. This was the mechanical equivalent of rubbing one out while wearing a boxing glove.

It had a single-seat spring-loaded saddle, which looked like it had been on a horse in a western at one time. There was no battery—everything worked off the (very dodgy) dynamo. Oh yeah, and it had a kick start that didn’t kick. When, and if, it started, it sounded like a squadron of bees flying low. With popping noises that sounded like ack-ack guns firing at them. It had three gears and a potluck gearbox. This was about as basic as it got. Riding to work was an adventure, especially on freezing-cold mornings. I had to go down a cobbled street called Forth Banks, which led to the Quayside. There was a sharp left-hander at the bottom. Icy cobbles and skinny tires are not good together, and every other morning I’d slide and end up under the bike. But I wasn’t the only one. There were lots of other blokes under their bikes, too. I made a lot of friends lying on the road under my BSA bike.

“Hey, mate, you all right?”

“Oh aye, lad. I think it’s my knee today. I did my ankle and me flask of tea yesterday.” We’d help each other up and continue on our way. I tried to tart my bike up by painting it black and silver, only to find that enamel paint reacts pretty badly with army khaki—it bubbled up so that the bike looked like a loofah with wheels on. This bike was not a chick magnet. Even old crones would titter as I pootled past.

The final straw was when I went for a ride one Sunday to Rowlands Gill. I was about three miles past Swalwell when the chain came off. After an hour of fiddling, I got it back on. Then the accelerator cable snapped again. I pushed the bastard seven miles home—mainly uphill with the odd down.

BSA stands for Birmingham Small Arms. I wish they had stuck to doing that. I can’t grumble too much, though. It did get me from A to B. From the pedestrian-slicing front license plate to the rear light, which came on when it felt like it, and the oil dripping from the engine casing, it was kinda cute in a “we’ll fight them on the beaches” sorta way.

Now, the Mods were coming to power, and scooters were the thing. Lambrettas and Vespas with loads of mirrors; parka coats with fur edging on the hood; and The Who. I was being left behind by “my generation.” I had to move quickly. I gave the bike away to a friend—who never spoke to me again.