Chapter 43

TINIAN

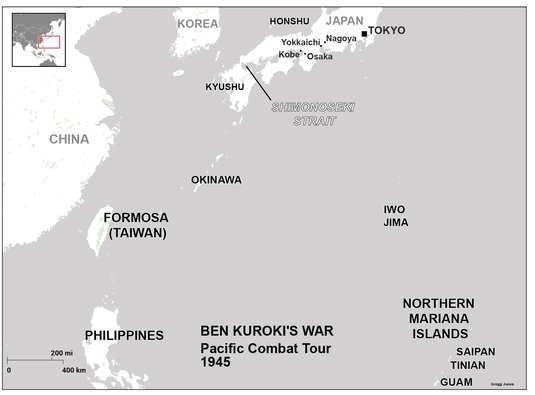

In the final week of 1944, after a journey of 3,700 miles west across the Pacific Ocean from Honolulu, Ben Kuroki and the crew of Honorable Sad Saki reached their destination: Tinian, a thirty-nine-square-mile chunk of coral-encrusted limestone in the Northern Marianas chain. The island’s most important feature was its proximity to Tokyo—a distance of fifteen hundred miles, or a fourteen-hour roundtrip flight for a bomb-laden B-29 Superfortress. Deployed to England for the early days of the Eighth Air Force bombing of Nazi Germany, Ben now found himself in the vanguard of the climactic air campaign against Japan.

Ben and his comrades emerged from Honorable Sad Saki for an introduction to their new home. In their first hours on the ground, they formed several impressions, none of them good. The island was hot, humid, and dangerous. The crew had no place to sleep, and no shelter from the tropical sun. Had anyone been expecting them? There was no evidence of it.

American soldiers had captured Tinian on August 1, 1944, after eight days of fighting that claimed the lives of 328 US soldiers and nearly 9,000 Japanese. Many of the Japanese soldiers had committed suicide rather than surrender. As soon as the island was secure, Navy Seabees came ashore and began clearing the island’s sugarcane fields to transform Tinian into a massive B-29 base. The entire northern end of the island was now covered by nearly eleven miles of runways, taxiways, and hardstands—enough to accommodate the four groups of the 313th Bombardment Wing, which included Ben’s 505th Bomb Group.

With the Seabees still focused on accommodations for the B-29s rather than their crews, Ben and his comrades set to work building a bivouac. For the enlisted personnel like Ben, canvas shelter halves would have to suffice until pyramid tents could be secured. Exercising the privilege of rank as always, the officers appropriated the sole Quonset hut near the airfield.

As the men worked, air-raid sirens periodically sent them scurrying for cover. The attackers were Japanese fighters and Bettys, twin-engine bombers that roared overhead to hit targets on the larger island of Saipan, whose southern tip lay only three miles off Tinian’s northern shore.

Tinian, Saipan, and the smaller island of Rota had been important sugar-producing islands under Japanese administration before the war, and lush fields of seven-foot-tall cane surrounded the 505th bivouac. Rumors swept the group that some of Tinian’s Japanese defenders had survived the fighting and were hiding in caves and cane fields, waiting to strike the American airmen and their B-29s. Nervous sentries reacted to random sounds and imagined threats by firing wildly into the fields, especially after nightfall.

Jim Jenkins and the Honorable Sad Saki crew feared their Japanese American gunner would be mistaken for an enemy soldier and shot on sight by a trigger-happy sentry. They pleaded with Ben to wear his US Army helmet at all times and they accompanied him to the mess tent and latrine. Ben stopped going to the latrine after dark. “I deserve a Purple Heart for bladder damage,” he joked with Jenkins and their squadron commander after a few days.1

Ben managed to make light of his predicament, but the danger was real. He had prepared himself for all imaginable challenges in the Pacific, but being mistaken for an enemy soldier and shot by his own comrades wasn’t one of them. With that grim possibility hanging over him every waking minute, Ben began to steel himself for actual combat against Japanese forces.

TEN WEEKS BEFORE BEN AND HIS crewmates landed on Tinian, Brigadier General Haywood “Possum” Hansell arrived on neighboring Saipan to head the bombing campaign designed to seal Japan’s defeat. Hansell went to work getting his inexperienced Superfortress pilots and gunners prepared for action. He first directed bombing raids on Truk atoll, providing an opportunity to practice formation flying and overwater flight while going up against light enemy defenses. After two raids on Truk he sent his crews to bomb airfields on the fortified Japanese island of Iwo Jima, a more formidable target that tested the daylight visual bombing skills of his men and their first night return. Hansell’s crews exhibited wildly inaccurate bombing in six training missions against Truk and Iwo Jima, but those problems would have to be worked out on the job.2

Hansell’s primary objective was the destruction of Japanese aircraft engine and assembly plants. His force had just over one hundred bombers on hand when Hansell issued his Twentieth Air Force crews their first strategic assignment: a strike on the Nakajima Aircraft Company’s engine plant in the crowded Tokyo suburb of Musashino, ten miles northwest of the Emperor’s Palace.

The raid took place November 24. Leading the way was a B-29 named Dauntless Dotty, piloted by a pair of celebrated B-17 pilots. Brigadier General Emmett “Rosie” O’Donnell, who had been a B-17 squadron commander in the Philippines at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, was the lead command pilot. Seated next to him in the copilot’s seat was Major Robert K. Morgan, who had piloted the Memphis Belle during the first year of the Eighth Air Force campaign against Nazi Germany.

On the flight to Tokyo, seventeen of 111 B-29s that got airborne aborted for various reasons. Another six failed to bomb because of mechanical issues. The aircraft that reached Tokyo rocketed into their bomb run with a 120-knot tailwind that increased their ground speed to about 445 miles per hour. The wind coupled with clouds that obscured the Nakajima plant led most of the aircraft to head for alternate targets. Only twenty-four B-29s bombed the Nakajima plant, while sixty-four dropped their ordnance on docks and urban areas.3

Pacific combat tour, 1945

The first Tokyo raid by Hansell’s forces—and the desultory results—were harbingers for what was to come. The B-29s executed occasional strikes on Iwo Jima’s airfields and some experimental incendiary raids on urban areas, but the high-altitude, daylight precision raids on aircraft factories in Japan fell far short of expectations. Clouds and high winds repeatedly undermined bombing accuracy.

By early January 1945, Hansell’s boss, the chronically impatient four-star general Hap Arnold, had seen enough. He relieved Hansell and replaced him with General Curtis LeMay. Arnold dispatched his handpicked hatchet man, General Lauris Norstad, to deliver a blunt warning. “If you don’t succeed,” Norstad told LeMay, “you will be fired.”4

Ben and the vanguard of the 505th Bomb Group had arrived in the waning days of Hansell’s command. The 313th Wing commanders on the ground had quickly sized up the new arrivals as deficient in key areas. They devised a month-long training program to whip the raw crews into shape flying simulated practice missions. On January 21, 1945, Curtis LeMay’s first full day as chief of the XXI Bomber Command, Ben logged his first mission as a B-29 gunner, bombing a Japanese airfield on the island of Truk. Ben and his crew logged two more raids in the closing days of January, twice bombing Japanese airfields on Iwo Jima.

For veterans of the European air war like Ben, the contrast between Japanese and German air defenses was striking. German antiaircraft fire was usually heavy and disciplined, and the fighter pilots were equally skilled. Ben had seen nothing of that skill or intensity in his first three missions against the Japanese. But would that still be the case over Japan’s home islands? Ben and his comrades could only wonder what awaited them when they finally got a chance to attack the Honshu heartland.