smile in response to your smile

smile in response to your smileChances are there have been plenty of changes around your house in the last month (and we’re not just talking diaper changes). Changes in your baby, as he or she progresses from cute-but-unresponsive blob to an increasingly active and alert tiny person (who sleeps a little less and interacts a little more). And changes in you, as you begin feeling less the bungling beginner and more the (semi-)seasoned veteran. After all, you’ve probably got one-handed diapering down pat, you’re a pro at burping (baby), and you can latch that little mouth onto your breast in your sleep (and often do). Of course, that still doesn’t mean you’re home free. While life with baby may be settling into a somewhat more predictable (though exhausting) routine, crying spells, cradle cap, and diaper contents may still be keeping you guessing (and making frequent calls to the doctor). But as your baby and your parental poise grow, you’ll be better equipped to face those everyday challenges without breaking a sweat. It might also help to keep in mind that you’ll be getting a reward this month for all those sleepless nights: your baby’s first truly social smile!

All babies reach milestones on their own developmental time line. If your baby seems not to have reached one or more of these milestones, rest assured, he or she probably will very soon. Your baby’s rate of development is normal for your baby. Keep in mind, too, that skills babies perform from the tummy position can be mastered only if there’s an opportunity to practice. So make sure your baby spends supervised playtime on his or her belly. If you have concerns about your baby’s development, check with the doctor. Premature infants generally reach milestones later than others of the same birth age, often achieving them closer to their adjusted age (the age they would be if they had been born at term), and sometimes later.

By two months, your baby … should be able to:

smile in response to your smile

smile in response to your smile

By the end of this month, most babies are able to lift their head to a 45-degree angle.

respond to a bell in some way, such as startling, crying, quieting

respond to a bell in some way, such as startling, crying, quieting

… will probably be able to:

vocalize in ways other than crying (e.g., cooing)

vocalize in ways other than crying (e.g., cooing)

on stomach, lift head 45 degrees

on stomach, lift head 45 degrees

… may even be able to:

hold head steady when upright

hold head steady when upright

on stomach, raise chest, supported by arms

on stomach, raise chest, supported by arms

roll over (one way)

roll over (one way)

grasp a rattle held to backs or tips of fingers

grasp a rattle held to backs or tips of fingers

pay attention to an object as small as a raisin (but make sure such objects are kept out of baby’s reach)

pay attention to an object as small as a raisin (but make sure such objects are kept out of baby’s reach)

reach for an object

reach for an object

say “Ah-goo” or similar vowelconsonant combination

say “Ah-goo” or similar vowelconsonant combination

… may possibly be able to:

smile spontaneously

smile spontaneously

bring both hands together

bring both hands together

on stomach, lift head 90 degrees

on stomach, lift head 90 degrees

laugh out loud

laugh out loud

squeal in delight

squeal in delight

follow an object held about 6 inches above the baby’s face and moved 180 degrees (from one side to the other), with baby watching all the way

follow an object held about 6 inches above the baby’s face and moved 180 degrees (from one side to the other), with baby watching all the way

Each practitioner will have a personal approach to well-baby checkups. The overall organization of the physical exam, as well as the number and type of assessment techniques used and procedures performed, will also vary with the individual needs of the child. But, in general, you can expect the following at a checkup when your baby is about two months old:

Questions about how you and baby and the rest of the family are doing at home, and about baby’s eating, sleeping, and general progress. About child care, if you are planning to return to work.

Questions about how you and baby and the rest of the family are doing at home, and about baby’s eating, sleeping, and general progress. About child care, if you are planning to return to work.

Measurement of baby’s weight, length, and head circumference, and plotting of progress since birth.

Measurement of baby’s weight, length, and head circumference, and plotting of progress since birth.

Physical exam, including a recheck of any previous problems.

Physical exam, including a recheck of any previous problems.

Even healthy babies spend a lot of time at the doctor’s office. Well-baby checkups, which are scheduled every month or two during the first year, allow the doctor to keep track of your baby’s growth and development, ensuring that everything’s on target. But they’re also the perfect time for you to ask the long list of questions you’ve accumulated since your last visit, and to walk away with a wealth of advice on how to keep your “well baby” well.

To make sure you make the most of a well-baby visit:

Time it right. When scheduling appointments, try to steer clear of nap time, lunchtime, and any time your baby’s typically fussy. And go for an empty waiting room, avoiding peak hours at the doctor’s office, if possible. Mornings are usually quieter because older children are in school—so, in general, a prelunch appointment will beat the four o’clock rush. And if you feel you’ll need extra time (you have even more questions and concerns than usual), ask for it so it can be scheduled into the visit. That way, you won’t feel quite as hurried.

Time it right. When scheduling appointments, try to steer clear of nap time, lunchtime, and any time your baby’s typically fussy. And go for an empty waiting room, avoiding peak hours at the doctor’s office, if possible. Mornings are usually quieter because older children are in school—so, in general, a prelunch appointment will beat the four o’clock rush. And if you feel you’ll need extra time (you have even more questions and concerns than usual), ask for it so it can be scheduled into the visit. That way, you won’t feel quite as hurried.

Fill’er up. A hungry patient is a cranky and uncooperative patient. So show up for your well-baby visits with a well-fed baby (once finger foods have been started, you can also bring a snack along for the waiting room). Keep in mind, however, that overfilling the tank just before the appointment may mean baby will be ripe for spitting once the exam begins.

Fill’er up. A hungry patient is a cranky and uncooperative patient. So show up for your well-baby visits with a well-fed baby (once finger foods have been started, you can also bring a snack along for the waiting room). Keep in mind, however, that overfilling the tank just before the appointment may mean baby will be ripe for spitting once the exam begins.

Dress for undressing success. When choosing baby’s wardrobe for the visit, think easy-on, easy-off. Skip outfits with lots of tiny buttons or snaps that take forever to do and undo, or snug clothes that are difficult to pull on and off. And don’t be too quick to undress; if your baby hates being naked, wait until the exam is about to begin before stripping down.

Dress for undressing success. When choosing baby’s wardrobe for the visit, think easy-on, easy-off. Skip outfits with lots of tiny buttons or snaps that take forever to do and undo, or snug clothes that are difficult to pull on and off. And don’t be too quick to undress; if your baby hates being naked, wait until the exam is about to begin before stripping down.

Write it down. Remember those two hundred questions you wanted to ask the doctor? You won’t, once you’ve spent twenty minutes in the waiting room and another twenty in the exam room trying to keep your baby (and yourself) calm. So instead of relying on your memory, bring a list you can read off. Pack a pen, too, so you can write down the answers to those questions, plus any other advice and instructions the doctor dispenses. You can also use it to record baby’s height, weight, immunizations received that visit, and so on.

Write it down. Remember those two hundred questions you wanted to ask the doctor? You won’t, once you’ve spent twenty minutes in the waiting room and another twenty in the exam room trying to keep your baby (and yourself) calm. So instead of relying on your memory, bring a list you can read off. Pack a pen, too, so you can write down the answers to those questions, plus any other advice and instructions the doctor dispenses. You can also use it to record baby’s height, weight, immunizations received that visit, and so on.

Make baby comfortable. Few babies enjoy the poking and prodding of a doctor’s exam—but most enjoy it even less when it takes place on a cold, uncomfortable exam table. Ask the doctor if he or she can perform most of the exam while baby’s on your lap.

Make baby comfortable. Few babies enjoy the poking and prodding of a doctor’s exam—but most enjoy it even less when it takes place on a cold, uncomfortable exam table. Ask the doctor if he or she can perform most of the exam while baby’s on your lap.

Trust your instincts. Your doctor sees your baby only once a month—you see your baby every day. Which means that you may notice subtle things the doctor doesn’t. If you feel something isn’t right with your child—even if you’re not sure what it is—make sure the doctor knows. Remember, you don’t need a medical degree to be a valuable partner in your baby’s health care. Sometimes the keenest diagnostic tool is a parent’s intuition.

Trust your instincts. Your doctor sees your baby only once a month—you see your baby every day. Which means that you may notice subtle things the doctor doesn’t. If you feel something isn’t right with your child—even if you’re not sure what it is—make sure the doctor knows. Remember, you don’t need a medical degree to be a valuable partner in your baby’s health care. Sometimes the keenest diagnostic tool is a parent’s intuition.

Developmental assessment. The examiner may actually put baby through a series of “tests” to evaluate head control, hand use, vision, hearing, and social interaction or may simply rely on observation plus your reports on what baby is doing.

Developmental assessment. The examiner may actually put baby through a series of “tests” to evaluate head control, hand use, vision, hearing, and social interaction or may simply rely on observation plus your reports on what baby is doing.

Immunizations, if baby is in good health and there are no other contraindications. See recommendations, page 226.

Immunizations, if baby is in good health and there are no other contraindications. See recommendations, page 226.

Guidance about what to expect in the next month in relation to such topics as feeding, sleeping, and development, and advice about infant safety.

Guidance about what to expect in the next month in relation to such topics as feeding, sleeping, and development, and advice about infant safety.

Questions you may want to ask, if the doctor hasn’t already answered them:

What reactions, if any, can you expect baby to have to the immunizations? How should you treat them? Which reactions should you call about?

What reactions, if any, can you expect baby to have to the immunizations? How should you treat them? Which reactions should you call about?

Also raise concerns that have come up over the past month about baby’s health, feeding issues, or family adjustment. Jot down information and instructions from the doctor. Record all pertinent information (baby’s weight, length, head circumference, birthmarks, immunizations, illnesses, medications given, test results, and so on) in a permanent health record.

Sure, breastfeeding’s ideal—the very best way to feed a baby. But as easy and practical as it is (now that you’ve, hopefully, gotten the hang of it), it does have its limitations, the most significant one being: You can’t breastfeed your baby unless you’re with your baby.

In some cultures, mothers and babies are never farther than a baby sling apart, making round-the-clock Breastfeeding not just doable but incredibly efficient, and making introducing the bottle completely unnecessary. But in our culture, even young babies are often apart from their mothers at a long enough distance and for a long enough time to require one or more supplementary feedings (that is, the replacement of breastfeeding sessions with a bottle of either expressed breast milk or formula).

Not bringing on the bottle? That’s fine too; there’s no rule that says a baby must be introduced to the bottle. There are a number of reasons some mothers choose to keep their babies bottle free:

They have a baby who rejects the bottle. Mothers who don’t have a compelling reason to supplement may then choose not to push the bottle agenda.

They have a baby who rejects the bottle. Mothers who don’t have a compelling reason to supplement may then choose not to push the bottle agenda.

Concern that if baby becomes dependent on a bottle, weaning will have to be accomplished twice: first from the breast, then from the bottle. These mothers usually start their babies on a cup as soon as they can sit supported, and use a cup for supplementary feedings of breast milk, and later for other drinks.

Concern that if baby becomes dependent on a bottle, weaning will have to be accomplished twice: first from the breast, then from the bottle. These mothers usually start their babies on a cup as soon as they can sit supported, and use a cup for supplementary feedings of breast milk, and later for other drinks.

MYTH: Supplementing with formula (or adding cereal to a bottle) will help baby sleep through the night.

Reality: Babies sleep through the night when they are developmentally ready to do so. Bringing on bottles of formula or introducing cereal prematurely won’t make that bright day (the one when you’ll wake up realizing you had a full night’s sleep) dawn any faster. Researchers have found no relationship between nighttime food and sleep.

MYTH: Breast milk alone isn’t enough for my baby.

Reality: Exclusively breastfeeding your baby for six months provides him with all the nutrients he needs. After six months, a combo of breast milk and solids can continue nourishing your growing baby well without adding formula.

MYTH: Giving formula to my baby won’t hurt my milk supply.

Reality: Any time you give something other than breast milk to your baby (formula or solid food), your milk supply diminishes. The less breast milk your baby takes, the less milk your breasts make. But waiting until breastfeeding is well established can minimize the effect supplementary bottles of formula have on lactation.

Though plenty of mothers choose not to introduce the bottle at all, and can manage to stick close enough to baby enough of the time that they don’t ever have to, most do introduce a bottle at some point (so they can have an occasional afternoon or evening away from baby, because they’re going back to work, or because the baby is not gaining sufficient weight on breast milk alone, for instance).

Even if you don’t plan on giving bottles regularly, it may be a good idea to express and freeze enough breast milk to fill six bottles—just in case. This will give you a backup supply if you become sick, you’re temporarily taking medication that might pass into your milk, or you’re called out of town unexpectedly. Even if your baby has never taken a bottle, it may be easier for him or her to accept one if it’s filled with familiar breast milk rather than with unfamiliar formula. See page 162 for freezer time limits on breast milk; as batches of the emergency cache expire, you may need to replace them with fresh ones.

Breast milk. Filling a bottle with expressed breast milk is usually uncomplicated (once you’ve mastered the art of pumping) and allows a mother to feed her baby a breast milk–only diet—even when she and baby are apart. (To avoid nipple confusion, wait until breastfeeding is well established before bringing on the bottle; see page 91).

Formula. Supplementing with formula, while obviously as easy as opening a can, may have drawbacks if started too early on in the breastfeeding relationship. When lactation is going well, a bottle of formula can interfere with the breast milk supply and actually create problems where there weren’t any. When lactation isn’t going well, a bottle of formula can make existing problems even worse. Once breastfeeding is well established (usually around six to eight weeks), however, many women find they can successfully combine breastfeeding and formula feeding (see page 90).

Ready to offer that first bottle? If you’re lucky, baby will take to it like an old friend—eagerly latching on and lapping up the contents. Or, maybe more realistically, he or she may take a little time to get warmed up to this unfamiliar food source. Keeping these tips in mind will help win baby over:

Time it right. Wait until your baby is both hungry (but not frantically so) and in a good mood before attempting to initiate the bottle.

Time it right. Wait until your baby is both hungry (but not frantically so) and in a good mood before attempting to initiate the bottle.

Hand it over. The first few bottles are more likely to be accepted if they are offered by someone other than you—preferably when you’re not in the same room for baby to complain to. The substitute feeder should cuddle and talk to the baby during the feeding, just as you would when nursing.

Hand it over. The first few bottles are more likely to be accepted if they are offered by someone other than you—preferably when you’re not in the same room for baby to complain to. The substitute feeder should cuddle and talk to the baby during the feeding, just as you would when nursing.

Keep it covered. If you have to offer that first bottle yourself, it may help to keep your breasts well camouflaged (don’t try to bottle feed braless or in a low-cut blouse; think heavy sweaters instead) and to distract the baby with background music, a toy, or another form of entertainment. Too much distraction, however, and your baby may want to play, not drink.

Keep it covered. If you have to offer that first bottle yourself, it may help to keep your breasts well camouflaged (don’t try to bottle feed braless or in a low-cut blouse; think heavy sweaters instead) and to distract the baby with background music, a toy, or another form of entertainment. Too much distraction, however, and your baby may want to play, not drink.

Pick the right nipple. If your baby tries out the nipple, then drops it with seeming disapproval, try a different type of nipple or warm it first the next time. For a baby who uses a pacifier, a nipple that is similar in shape may work.

Pick the right nipple. If your baby tries out the nipple, then drops it with seeming disapproval, try a different type of nipple or warm it first the next time. For a baby who uses a pacifier, a nipple that is similar in shape may work.

Be a sneak. If you’re meeting resistance to the bottle, sneak it in during sleep. Have your bottle giver pick up your sleeping baby and try to give the bottle then. In a few weeks baby may accept the bottle when awake.

Be a sneak. If you’re meeting resistance to the bottle, sneak it in during sleep. Have your bottle giver pick up your sleeping baby and try to give the bottle then. In a few weeks baby may accept the bottle when awake.

Some women choose not to supplement with formula for other reasons, including the desire to breastfeed for the recommended one year or longer (studies show a significant relationship between formula supplementation and early weaning) and to prevent or delay allergy from cow’s milk formula when there’s a family history of allergies.

Don’t have enough expressed milk to make up a complete bottle? No need to throw all that hard work down the drain. Instead, mix formula with the expressed milk to fill the bottle. Less waste—and your baby will be getting enzymes from the breast milk that will help digest the formula better.

When to begin. Some babies have no difficulty switching from breast to bottle and back again right from the start, but most do best with both if the bottle isn’t introduced until at least three weeks, preferably five weeks. Earlier than this, bottle feedings may interfere with the successful establishment of breastfeeding, and babies may experience nipple confusion because dining at breast and bottle call for different sucking techniques. Much later than this, many babies reject rubber nipples in favor of their beloved mama’s familiar fleshy ones.

Occasionally, formula supplementation is recommended because baby isn’t doing well on breast milk alone. This often leaves a mother feeling conflicted. On the one hand, she hears that giving a bottle in such a situation may totally wipe out her chances of breastfeeding successfully; on the other, she’s told by the doctor that if she doesn’t start supplementing her baby’s diet with formula, the health consequences could be serious. The best solution in many such cases is the supplemental nutrition system, shown on page 167, which provides a baby with the formula he or she needs to begin thriving, while stimulating mom’s breasts to produce more breast milk.

How much breast milk or formula to use. One of the beauties of breastfeeding is that baby eats to appetite, not to a specified number of ounces you’re pushing. As soon as you start using a bottle, it’s easy to succumb to the numbers game. Resist. Tell your baby’s care provider (and yourself) to give your baby only as much as he or she wants, with no prodding to finish any particular amount. The average nine-pounder may take as much as 6 ounces at a feeding, or less than 2.

Getting baby used to the bottle. If your schedule will require your regularly missing two feedings during the day, switch to the bottle one feeding at a time, starting at least two weeks before you plan to go back to work. Give your baby a full week to get used to the single bottle feeding before moving on to two. This will help not only baby but also your body adjust gradually, if you are planning to supplement with formula rather than breast milk. The wonderful supply-and-demand mechanism that controls milk production will cut back as you do, making you more comfortable when you’re finally back on the job.

Keeping yourself comfortable. If you plan to give a bottle only occasionally, nursing thoroughly on (or expressing from) both breasts before going out will make fullness and leakage less of a problem. Be sure your baby won’t be fed too close to your return (less than two hours is probably too close) so that if you are uncomfortably full, you can nurse as soon as you get home.

Whether you choose to supplement with breast milk or formula, you should keep in mind that it will probably be necessary for you to express milk if you will be away from your baby for more than three or four hours, to help prevent clogging of milk ducts, leaking, and a diminishing milk supply. The milk can be either collected and saved for future feedings or disposed of.

“My son is five weeks old, and I thought he would be smiling real smiles by now, but he doesn’t seem to be.”

Cheer up. Even some of the happiest babies don’t start true social smiling until six or seven weeks of age. And once they start smiling, some are just naturally more smiley than others. You’ll be able to distinguish the first real smile from those tentative practice ones by the way the baby uses his whole face—not just his mouth. Though babies don’t smile until they’re ready, they’re ready faster when they’re talked to, played with, and cuddled a lot. So smile at your baby and talk to him often, and very soon he’ll be matching you grin for grin.

Think those adorable “ba-ba-ba”s are just baby babble? They’re actually the beginnings of spoken language—baby’s first attempts at figuring out how the other half (the adult half, that is) speaks. But here’s an interesting baby factoid that researchers (who have spent a great deal of time studying what comes out of the mouths of babes) have uncovered: These early articulations of language typically come out of the right side of baby’s mouth (the side controlled by the left side of the brain, the hemisphere that’s in charge of language). When babies babble just for pleasure’s sake (not for language practice), they get the whole mouth moving. When they smile, they apparently use the left side of the mouth (which is mission control for emotions).

But before you try this at home with your baby, here’s something else you need to know: The differences in mouth movements are so subtle that you’d have to have a Ph.D. in linguistics to distinguish a left movement from a right. So leave such analyses to the folks in the lab. Instead, sit back and enjoy all those adorable sounds—no matter which side of baby’s mouth they come out of.

“My six-week-old baby makes a lot of breathy vowel sounds but no consonants at all. Is she on target speechwise?”

With young babies, the “ayes”—and the a’s, e’s, o’s, and u’s—have it. It’s the vowel sounds they make first, somewhere between the first few weeks and the end of the second month. At first the breathy, melodic (and adorable) cooing and throaty gurgles seem totally random, and then you’ll begin to notice they’re directed at you when you talk to your baby, at a stuffed animal who’s sharing her play yard, at a mobile beside her that’s caught her eye, at her own reflection in the crib mirror, or even at a duck on the bumper. These vocal exercises are often practiced as much for her own pleasure as for yours; babies actually seem to love listening to their own voices. In the process, baby is also making verbal experiments and discovering which combinations of throat, tongue, and mouth actions make what sounds.

For mommy and daddy, cooing is a welcome step up from crying on the communication ladder. And it’s just the beginning. Within a few weeks to a few months, baby will begin adding laughing out loud (usually by three and a half months), squealing (by four and a half months), and a few consonants to her repertoire. The range for initiating consonant vocalizations is very broad—some make a few consonant-like sounds in the third month, others not until five or six months, though four months is about average.

When babies begin experimenting with consonants, they usually discover one or two at a time, and repeat the same single combination (ba or ga or da) over and over and over. The next week, they may move on to a new combination, seeming to have forgotten the first. They haven’t, but since their powers of concentration are limited, they usually work on mastering one thing at a time. They also love repetition.

The roads to communication with a baby are endless, and each parent travels some more than others. Here are some you may want to take, now or in the months ahead:

Do a running commentary. Don’t make a move, at least when you’re around your baby, without talking about it. Narrate the dressing process: “Now I’m putting on your diaper … here goes the T-shirt over your head … now I’m buttoning your overalls.” In the kitchen, describe the washing of the dishes, or the process of seasoning the pasta sauce. During the bath, explain about soap and rinsing, and that a shampoo makes the hair shiny and clean. It doesn’t matter that your baby hasn’t the slightest inkling of what you’re talking about. Blow-by-blow descriptions help get you talking and baby listening—thereby starting him or her on the path to understanding.

Ask a lot. Don’t wait until your baby starts having answers to start asking questions. Think of yourself as a reporter, your baby as an intriguing interviewee. The questions can be as varied as your day: “Would you like to wear the red pants or the green overalls?” “Isn’t the sky a beautiful blue today?” “Should I buy green beans or broccoli for dinner?” Pause for an answer (one day your baby will surprise you with one), and then supply the answer yourself, out loud (“Broccoli? Good choice”).

Give baby a chance. Studies show that infants whose parents talk with them rather than at them learn to talk earlier. Give your baby a chance to get in a coo, a gurgle, or a giggle. In your running commentaries, be sure to leave some openings for baby’s comments.

Keep it simple—some of the time. Though right now your baby would probably derive listening pleasure from a dramatic recitation of the Gettysburg Address or an animated assessment of the economy, as he or she gets a bit older, you’ll want to make it easier to pick out individual words. So at least part of the time, make a conscious effort to use simple sentences and phrases: “See the light,” “Bye-bye,” “Baby’s fingers, baby’s toes,” and “Nice doggie.”

Put aside pronouns. It’s difficult for a baby to grasp that “I” or “me” or “you” can be mommy, or daddy, or grandma, or even baby—depending on who’s talking. So most of the time, refer to yourself as “mommy” or “daddy” (or “grandma”) and to your baby by name: “Now Daddy is going to change Amanda’s diaper.”

Raise your pitch. Most babies prefer a high-pitched voice, which may be why women’s voices are usually naturally higher-pitched than men’s, and why most mothers’ (and fathers’) voices climb an octave or two when addressing their infants. Try raising your pitch when talking directly to your baby, and watch the reaction. (A few infants prefer a lower pitch; experiment to see which appeals to yours.)

Bring on the baby talk … or not. If the silly stuff (“Who’s my little bunny-wunny?”) comes naturally to you, babble away in baby talk. If it doesn’t, feel free to skip it (see next page). If you’re big on baby talk, don’t forget to throw some correct, more adult English into your conversations with your infant, too, so that he or she won’t grow up thinking all words end with a y or ie.

Stick to the here and now. Though you can muse about almost anything to your baby, there won’t be any noticeable comprehension for a while. As comprehension does develop, you will want to stick more to what the baby can see or is experiencing at the moment. A young baby doesn’t have a memory for the past or a concept of the future.

Imitate. Babies love the flattery that comes with imitation. When baby coos, coo back; when he or she utters an “Ahh,” utter one, too. Imitation will quickly become a game that you’ll both enjoy, and which will set the foundation for baby’s imitating your language—it will also help build self-esteem (“What I say matters!”).

Set it to music. Don’t worry if you can’t carry a tune—little babies are notoriously undiscriminating when it comes to music. They’ll love what you sing to them whether it’s a current hit, an old favorite from high school, or just some nonsense you’ve set to a familiar tune. If your sensibilities (or your neighbors’) prohibit a song, then singsong will do. Most nursery rhymes entrance even young infants (invest in an edition of Mother Goose if your memory fails you). And accompanying hand gestures, if you know some or can make some up, double the delight. Your baby will quickly let you know which are favorites, and which you’ll be expected to sing over and over—and over—again.

Read aloud. Though at first the words will have no meaning to baby, it’s never too early to begin reading some simple rhyming stories or board books out loud. When you aren’t in the mood for baby talk and crave some adult-level stimulation, share your love of literature (or recipes or gossip or politics) with your little one by reading what you like to read, aloud.

Take your cues from baby. Incessant chatter and song can be tiresome for anyone, even an infant. When your baby becomes inattentive to your wordplay, closes or averts his or her eyes, becomes fussy or cranky, or otherwise indicates the verbal saturation point has been reached, give it a rest.

Following the two-syllable, one-consonant sounds (a-ga, a-ba, a-da) come singsong strings of consonants (da-da-dada-da-da) called “babble,” at six months on the average. By eight months, many babies can produce word-like double consonants (da-da, ma-ma, ha-ha), usually without associating any meaning with them until two or three months later. (To fathers’ delight and mothers’ dismay, dada generally comes before mama.) Mastery of all the consonants doesn’t come until much later, often not until four or five years of age—occasionally even later.

“Our baby doesn’t seem to make the same kind of cooing sounds that his older brother made at six weeks. Should we be concerned?”

Some normal babies develop language skills earlier than average, some later. About 10 percent of babies start cooing before the end of the first month and another 10 percent don’t start until nearly three months, the rest somewhere in between. Some start with strings of consonants before the 4½-month mark; others don’t string consonants until past 8 months. The early verbalizers may end up very strong in language skills (though the evidence isn’t that clear); those who lag far behind, in the lowest 10 percent, may have a physical or developmental problem, but this isn’t clear either. Certainly, it’s too early to be concerned that this might be the case with your baby, since he’s still well within the norm.

If it seems to you over the next several months that your baby consistently, in spite of your encouragement, falls far below the monthly milestones in each chapter, speak to his doctor about your concerns. A hearing evaluation or other tests may be in order. It may turn out that you are so busy that you aren’t really noticing your baby’s vocal achievements (this sometimes happens with second children)—or that everyone else in the household (including his older brother) is making so much noise he can’t get a coo in edgewise. In the less likely case that there actually is a problem, early intervention is often able to remedy it.

“Other parents seem to know how to talk to their babies. But I don’t know what to say to my six-week-old, and when I try, I feel like an absolute idiot. I’m afraid that my inhibitions will slow down his language development.”

They’re tiny. They’re passive. They can’t talk back. And, yet, for many novice mothers and fathers, newborn babies are the most intimidating audience they’ll ever face. The undignified, high-pitched baby talk that seems to come naturally to other parents eludes them, leaving them tonguetied—and feeling guilty over the awkward silence that envelops the nursery.

Though your baby will learn your language even if you never learn his, his speech will develop faster and better if you make a conscious effort at early communication. Babies who aren’t communicated with at all suffer not just in language development but in all areas of growth. But that rarely happens. Even the parent who is bashful about baby talk communicates with his or her baby all day long—while cuddling him, responding to his crying, singing him a lullaby, saying, “It’s time for a walk,” or muttering, “Oh, not the phone again.” Parents teach language when they talk to each other as well as when they talk to their baby; babies pick up almost as much from secondhand dialogue as they do when they’re part of a conversation.

So although it’s not likely that your baby is going to spend the next year in the company of a silent parent, there are ways to expand your baby-word power, even if you’re the kind of adult to whom baby talk doesn’t come naturally. The trick is to start practicing in private, so the embarrassment of gurgling and babbling to your baby in front of other adults won’t cramp your conversation style. If you don’t know where to begin, use the tips on the previous page as a guideline. As you grow more comfortable with baby talk, you’ll likely find yourself slipping into it unawares, even in the company of adults (“Doesn’t that risotto look yummy-yummy for the tum-tummy?”).

“My wife is French, and she wants to speak French to our baby exclusively; I speak English. I think it would be wonderful for our daughter to speak a second language, but wouldn’t it be confusing at this age?”

Because fluency in another language isn’t necessary to function and succeed in most parts of our country (as it is elsewhere), Americans are sadly lagging behind the rest of the world in the ability to converse in anything other than their own native tongue. It’s generally agreed that teaching a child a second language gives her an invaluable skill, and may help her to think in different ways, possibly even improving her future academic performance in other areas. If the language is one that her forebears spoke or some of her relatives speak, it also gives her a significant link with her roots.

There is less agreement on just when to introduce the second language, however. Most experts suggest beginning as soon as a baby is born so that the second language is “acquired” along with the first, not “learned,” as it would be when introduced later. Others believe that this puts the child at a disadvantage in both languages—though probably for only a short time. They generally recommend waiting until a child is two and a half or three before putting on the Berlitz. By this time she usually has a pretty good grasp of English but is still able to pick up a new language easily and naturally.

It’ll probably be almost a year before your baby speaks that first word—two years or more before words are strung into phrases and then sentences, perhaps a year or longer before most of those sentences are easily comprehensible. But long before your baby is communicating verbally, he or she will be communicating in a variety of other ways. In fact, look and listen closely now and you’ll find that your baby’s already trying to speak to you—not in so many words, but in so many behaviors and gestures.

No dictionary of baby communication can tell you what your baby’s saying. Rather, the key to understanding this non-verbal communication is observation—patient, careful observation. Observing your child will speak volumes about his or her personality, preferences, and needs, months before your child can speak at all. For example, does your baby wiggle and fuss uncomfortably when she’s undressed before her bath? That may mean that she dislikes the cold air on her naked body—or just doesn’t like the sensation of being naked at all. Keeping her covered as much as possible before lowering her into the bath will help ease her discomfort.

Or does your baby make coughing sounds around the time he’s ready for a nap? Coughing might be your baby’s way of telling you that he’s getting tired—long before early fatigue melts down into crankiness.

Or does your baby frantically stuff her fist into her mouth when she’s due for a feeding, before she starts wailing loudly? That could be her hunger cue—her first message to you that she’s ready to eat (the second, crying, will make the feeding much more difficult for both of you to accomplish). By observing your baby’s behaviors and gestures, you’ll notice patterns that will start to make sense—and will help you make sense of what baby’s telling you.

And listening to what baby tells you not only makes your job easier (you can provide what baby wants promptly, rather than figuring it out through trial, error, and tears) but also lets your baby know that what he or she has to say matters, an important first step on the road to becoming a confident, secure, successful, and emotionally mature person.

Whether you start now or in a couple of years, there are several approaches to encouraging a child to pick up a second language. One parent can speak English and the other the foreign tongue (as your spouse suggests), or both parents can speak the foreign language (with the expectation the child will pick up English in school and elsewhere), or a grandparent, sitter, or au pair can speak the foreign language and the parents English (usually the least successful of the methods). None of the methods of teaching a second language is particularly successful if the “teacher” isn’t fluent in the language.

Experts recommend you forget about “giving lessons in” a second language and instead immerse your child in it—play games (and, as you child grows, computer games) in it, read books in it (many popular children’s books have been translated from English into other languages), sing songs in it, listen to CDs and watch DVDs in it, visit with friends who are fluent in it, and, if possible, visit places where the language is spoken. Whoever is speaking the second language should speak it exclusively to the child, resisting the temptation to resort to English or to translate if the child seems to be struggling with comprehension. Expect your child to go through some periods of mixing the two languages in the beginning, but, eventually, a separation of the two will occur. During the school years, the child should be taught to read and write in the second language in order for it to take on greater usefulness and significance. If classes aren’t available at school, tutoring or computer-programmed learning may be a good idea.

Your baby won’t remember much, if anything, about the first three years of life, but according to researchers, those three years will have a huge impact on the quality of your child’s life—in some ways more than any of the others that follow.

What makes those first three years—years filled primarily with eating, sleeping, crying, and playing, the years before formal learning even begins—so vital to your child’s ultimate success in school, in a career, in relationships? How can a period of time when your child is so clearly unformed be so critical to the formation of the human being your child will eventually become? The answer is fascinating, complex, and still evolving. Here’s what scientists believe so far.

Research shows that a child’s brain grows to 90 percent of its adult capacity during those first three years—granted, a lot of brain power for someone who can’t yet tie his or her shoes. During these three phenomenal years, brain “wiring” occurs. (“Wiring” is when the crucial connections are made linking brain cells.) By the third birthday, somewhere around one thousand trillion connections will have been made.

With all this activity, however, a child’s brain is very much a work in progress at age three. More connections are made until age ten or eleven, at which point the brain starts specializing for better efficiency, eliminating connections that are rarely used (this pattern continues throughout life, which is why adults end up with only about half the brain connections a three-year-old has). Changes continue to take place well past puberty, with important parts of the brain still continuing to change throughout life.

While your child’s future—like his or her brain—is far from fully cast at age three, it does appear that those early years do form the mold that will shape the person he or she will become. And the greatest influence during those formative years is you. Research shows that the kind of care a child receives during that time determines to a large extent how well those brain connections will be made, how much that little brain will develop, how successful, how content, how confident, and how competent to handle life’s challenges that child will be.

Feeling daunted and overwhelmed by the task that’s been handed you? Don’t be. Most of what any loving parent does intuitively (with no training, without the addition of flash cards or special mind-expanding programs) is exactly what your child—and your child’s brain—needs to develop to his or her greatest potential. Consider:

Every time you touch, hold, cuddle, hug, or respond to your baby with warm responsive care (all things you do anyway), you’re positively affecting the way your child’s brain forms connections. By reading, talking, singing, making eye contact, or cooing to your baby, you’re helping your baby’s brain reach its full potential. And through your positive parenting, you’ll be teaching your child social and emotional skills that will actually boost your child’s intellectual development as he or she gets older; the more socially and emotionally confident a child is, the more likely that child will be motivated to learn and to take on new challenges with enthusiasm and without fear of failure.

Every time you touch, hold, cuddle, hug, or respond to your baby with warm responsive care (all things you do anyway), you’re positively affecting the way your child’s brain forms connections. By reading, talking, singing, making eye contact, or cooing to your baby, you’re helping your baby’s brain reach its full potential. And through your positive parenting, you’ll be teaching your child social and emotional skills that will actually boost your child’s intellectual development as he or she gets older; the more socially and emotionally confident a child is, the more likely that child will be motivated to learn and to take on new challenges with enthusiasm and without fear of failure.

Children whose basic needs are met in infancy and early childhood (she’s fed when hungry, changed when wet, held when frightened) develop a sense of trust in others and a high level of self-confidence. Researchers have found that children reared in such nurturing environments have fewer behavioral problems in school later on, and are emotionally more capable of positive social relationships.

Children whose basic needs are met in infancy and early childhood (she’s fed when hungry, changed when wet, held when frightened) develop a sense of trust in others and a high level of self-confidence. Researchers have found that children reared in such nurturing environments have fewer behavioral problems in school later on, and are emotionally more capable of positive social relationships.

By monitoring and helping to regulate your baby’s impulses and behaviors during the early years (explaining she can’t bite, telling him not to grab a toy), you will eventually teach your child self-control. Setting limits that are fair and age-appropriate and enforcing them consistently will enable your child to be less likely to be anxious, frightened, impulsive, or to rely on violent means to resolve conflicts later on in life, say researchers. He or she will also be more capable of intellectual learning because of the solid emotional foundation you have provided.

By monitoring and helping to regulate your baby’s impulses and behaviors during the early years (explaining she can’t bite, telling him not to grab a toy), you will eventually teach your child self-control. Setting limits that are fair and age-appropriate and enforcing them consistently will enable your child to be less likely to be anxious, frightened, impulsive, or to rely on violent means to resolve conflicts later on in life, say researchers. He or she will also be more capable of intellectual learning because of the solid emotional foundation you have provided.

Likewise, any caregiver who spends a significant amount of time with your child should provide the same kind of stimulation, the same kind of responsiveness, the same kind of positive discipline. High-quality child care will help ensure that your baby’s brain gets what it needs: lots of nurturing.

Likewise, any caregiver who spends a significant amount of time with your child should provide the same kind of stimulation, the same kind of responsiveness, the same kind of positive discipline. High-quality child care will help ensure that your baby’s brain gets what it needs: lots of nurturing.

Routine medical care is important, too, ensuring that your child will be screened regularly for any medical or developmental issues that could slow intellectual, social, or emotional growth. It will also allow for early intervention should a problem be uncovered, which could prevent that problem from holding your child back.

Routine medical care is important, too, ensuring that your child will be screened regularly for any medical or developmental issues that could slow intellectual, social, or emotional growth. It will also allow for early intervention should a problem be uncovered, which could prevent that problem from holding your child back.

And here’s probably the most important thing to keep in mind. Helping your child reach his or her potential is different from trying to change the person your child is; encouraging intellectual development is different from pushing it; providing stimulating experiences is different from scheduling in the kind of overload that leads to burnout. It’s easy to avoid crossing that line from just enough parental interaction and involvement to too much by taking your cues from your baby—who, when it comes to getting what he or she needs, can be wise even beyond your years. Watch and listen carefully, and you’ll almost always know what’s best for your child.

“I get together regularly with a parents’ group, and inevitably they all start comparing what their babies have been doing. It makes me crazy—and worried about whether my son is developing fast enough.”

If there’s anything more anxiety provoking than a roomful of pregnant women comparing bellies, it’s a roomful of recently delivered parents comparing babies. Just as no two pregnant bellies are exactly alike, neither are any two babies. Developmental norms (such as those found in each chapter of this book) are useful for comparing your baby to a broad range of normal infants in order to assess her progress and identify any lags. But comparing your baby with someone else’s child, or with an older one of your own, can only result in a lot of unnecessary fears and frustrations. Two perfectly “normal” babies can develop in different areas at completely different clips—one may forge ahead in vocalizing and socializing, another in physical feats, such as turning over. Differences between babies become even more marked as the first year progresses—one baby may crawl very early but not walk until fifteen months, another may never learn to crawl at all but suddenly start taking steps at ten months. Then, too, a parent’s assessment of her baby’s progress is highly subjective—and not always completely accurate. One may not even recognize baby’s frequent coos as the beginnings of language, while another may hear one coo and swear, “He said ‘dada’!”

All of this said, it’s easier to intellectualize that comparing babies isn’t a good idea than to actually stop doing it or avoid those who do. Many compulsive comparers can’t sit within ten feet of another parent-with-baby on a bus, in a doctor’s waiting room, or at the park without launching an assault of outwardly innocent queries that lead to the inevitable comparisons (“What an adorable baby! She’s sitting already? How old is she?”). The best advice, if you can’t completely manage to “mind your own baby,” is to remember how meaningless these comparisons really are. Your baby, like your belly before him, is one of a kind.

“My baby’s pediatrician says that immunization is perfectly safe. But I’ve heard a few stories about serious reactions, and I worry about my daughter getting the shots.”

We live in a society that considers good news to be no news. A story on the positive effects of immunizations cannot compete with one on the extremely rare instances of serious complications associated with them. So it is likely that today’s parents have heard more about the risks of immunization than the benefits. And, yet, as your pediatrician has doubtless told you, for most infants those benefits continue to far outweigh the risks.

Not too many years ago in the United States, the most common causes of infant death were infectious diseases, such as diphtheria, typhoid, and smallpox. Measles and whooping cough were so common that all children were expected to get them, and thousands, especially infants, died or were permanently handicapped by these illnesses. Parents dreaded the coming of summer and the infantile paralysis (polio) epidemics that seemed invariably to arrive with it, killing or disabling thousands of infants and children. Today, smallpox has been virtually eliminated, and diphtheria and typhoid are extremely rare. Only a small percentage of children are stricken with measles or whooping cough each year, and infantile paralysis is a disease parents are not only no longer afraid of, but often aren’t even familiar with. An American baby is now much more likely to die because of not being strapped into a car seat than from a communicable disease. Without a doubt, immunization has made childhood safer for children.

Immunization is based on the fact that exposure to weakened or dead disease-producing microorganisms (in the form of vaccines) or to the poisons (toxins) they produce, rendered harmless by heat or chemical treatment (then called toxoids), will cause an individual to produce the same antibodies that would develop if the person had actually contracted the disease. Armed with the special memory that is unique to the immune system, these antibodies will “recognize” the specific microorganisms, should they attack in the future, and destroy them.

Even the ancients recognized that when people survived a particular disease, they weren’t likely to contract it again, and those who had recovered from the plague were sometimes called upon to care for new victims. Although some societies attempted crude forms of immunization, it wasn’t until Edward Jenner, a Scottish physician, decided to test the old belief that a person who contracted the lesser disease cowpox would never get smallpox, that modern immunization was born. In 1796, Jenner smeared pus from the sores of a milkmaid infected with cowpox on two small cuts in the arm of a healthy eight-year-old boy. The child developed a slight fever a week later, then a couple of small scabs on his arm. When exposed to smallpox later, he remained healthy. He had become immune.

Most worries about immunization—though perfectly understandable—are unfounded. Don’t let the following myths keep you from immunizing your baby:

MYTH: Giving so many shots together isn’t safe.

Reality: Studies have shown that vaccinations are just as safe and effective when given together. There are many combination vaccines that have been used routinely for years (MMR, DTaP). Recently approved and already in use by many doctors is the Pediarix vaccine that combines DTaP, polio, and hep B in a single shot. Researchers are continuing to develop combo vaccines that may become approved for use in the near future. The best part about these combination vaccines: fewer total shots for your baby—something you’re both likely to appreciate.

MYTH: Shots are very painful for a baby.

Reality: The pain of a vaccine is only momentary and, compared to the pain of the serious diseases the immunization is protecting against, insignificant. And there are ways of minimizing the pain your baby feels. Studies show that babies who get shots while they are being held and distracted by their parents cry less, and those who are breastfed immediately before or during the immunization experience less pain. You can also ask your baby’s doctor about giving a sugar solution just before the shot or using an anesthetic cream an hour earlier (which the doctor will have to prescribe).

MYTH: If everyone else’s children are immunized, mine can’t get sick.

Reality: Some parents believe that they don’t have to immunize their own children if everyone else’s children are immunized—since there won’t be any diseases to catch. That theory doesn’t hold up. First of all, there’s the risk that other parents are subscribing to the same myth, which means their children won’t be immunized, either, creating the potential for an outbreak of a preventable disease. Second, unvaccinated children put vaccinated children at risk for the disease as well (vaccines are about 90 percent effective; the high percentage of immunized individuals limits the spread of disease)—so not only might you be hurting your child, you might also be hurting your child’s friends. Third, unvaccinated children can catch whooping cough (pertussis) not only from other unvaccinated children, but also from adults. That’s because the vaccine that protects against it isn’t given after age seven; immunity has largely worn off by adulthood; and the disease, while still highly contagious, is so mild in adults that it’s usually not diagnosed—which means that adults who don’t realize they have whooping cough can inadvertently spread it to babies, who are much more vulnerable to its effects.

MYTH: One vaccine in a series gives a child enough protection.

Reality: Researchers have found that skipping vaccines puts your child at increased risk for contracting the diseases, especially measles and pertussis. So if the recommendations are for a series of four shots, make sure your child receives all the necessary shots so he or she is not left unprotected.

MYTH: Multiple vaccines for such young babies put them at increased risk for other diseases.

Reality: There is no evidence that multiple immunizations increase the risk for diabetes, infectious disease, or other illnesses. Neither is there any evidence to date that there is a connection between multiple vaccines and allergic diseases such as asthma.

The immunization process has come a long way since that early experiment. The first widely administered type of immunization, the smallpox vaccination, was so successful that it is no longer considered necessary. For now, at least, the disease seems to have been eradicated from the entire globe. Plenty of progress has been made with other serious scourges as well, and it’s hoped that immunization will someday wipe out most of them, too.

But while immunization clearly saves thousands of young lives each year, it’s not perfect. Though most children have only a mild reaction to certain vaccines, some become ill, a very few seriously so. Some types of vaccine have been suspected of causing, on rare occasions, permanent damage, even death. Still, the tremendous benefits of protection from serious disease far outweigh the very small risks of immunization for all but high-risk children—clearly making vaccination the very best bet for your baby. And as minimal as the risks are, they can be reduced even further by taking precautions to make sure your baby is safely vaccinated. Here’s how:

Be sure the doctor gives your baby a thorough checkup before giving a vaccination to be certain no serious illness is developing that is not yet apparent; shots should be postponed when a baby is significantly ill. (A mild illness, such as a cold, is not reason to postpone a shot.)

Be sure the doctor gives your baby a thorough checkup before giving a vaccination to be certain no serious illness is developing that is not yet apparent; shots should be postponed when a baby is significantly ill. (A mild illness, such as a cold, is not reason to postpone a shot.)

Read the one-page CDC vaccine information statements (VISs) that should be provided by the doctor each time a routine vaccine is given to your child. (The statements are also available on the Web at www.cdc.gov.)

Read the one-page CDC vaccine information statements (VISs) that should be provided by the doctor each time a routine vaccine is given to your child. (The statements are also available on the Web at www.cdc.gov.)

Observe your baby carefully for 72 hours after the vaccination (especially during the first 48), and report any severe reactions (see page 232) or very unusual behavior to the doctor immediately. Also report any less severe reactions at your next visit.

Observe your baby carefully for 72 hours after the vaccination (especially during the first 48), and report any severe reactions (see page 232) or very unusual behavior to the doctor immediately. Also report any less severe reactions at your next visit.

Ask the doctor to enter the vaccine manufacturer’s name and the vaccine lot/batch number in your child’s records, along with any reactions you report. Be sure to get a copy of the information for your own records as well. Severe reactions should be reported by the doctor or by you to VAERS (Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System); www. vaers.org.

Ask the doctor to enter the vaccine manufacturer’s name and the vaccine lot/batch number in your child’s records, along with any reactions you report. Be sure to get a copy of the information for your own records as well. Severe reactions should be reported by the doctor or by you to VAERS (Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System); www. vaers.org.

When the next shot is scheduled, remind your baby’s doctor about any previous reactions to the vaccine.

When the next shot is scheduled, remind your baby’s doctor about any previous reactions to the vaccine.

If you have any fears about vaccine safety, discuss them with your baby’s doctor.

If you have any fears about vaccine safety, discuss them with your baby’s doctor.

It helps to know what the needle that’s headed your baby’s way is loaded with. The following is a guide to immunizations your child will probably receive in the first year and beyond:

Diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP). Immunization against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (whooping cough) is crucial, since all can cause serious illness and death. DTaP (which contains diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and an acellular pertussis vaccine) has fewer serious side effects than the older DTP (which contains a whole-cell pertussis vaccine) and is now the vaccine of choice. Though there were rare reports, not fully substantiated, of a link between the old vaccine and brain damage, there have been no such reports with the new one.

Your child needs five DTaP shots. DTaP is recommended at two, four, and six months, fifteen to eighteen months, and between four and six years.

Up to one-third of children who get DTaP have very mild local reactions where the shot was given, such as tenderness, swelling, or redness, usually within two days of getting the shot. Some children are fussy or will lose their appetite for a few hours or perhaps a day or two. Fever is also a common reaction. These reactions are more likely to occur after the fourth and fifth doses than after the earlier doses. Occasionally, a child will have a more serious side effect, such as a fever of over 104°F. Rarely, a child will cry continuously (for three or more hours) after receiving the DTaP. Even rarer are convulsions, which can result not from the vaccine itself but rather from a high fever accompanying it in a few children (see page 232). Research has shown that any seizures resulting from such vaccine-induced fever do not lead to lasting problems; a suggested link between these seizures and autism has not been found. Research also shows that there is no correlation between the vaccine and a greater risk of SIDS.

In certain circumstances, a doctor may decide to omit the pertussis vaccine (and just administer the DT) if the baby’s previous reactions to DTaP were severe. And a doctor may delay giving the DTaP (or not give it at all) if a child had a severe allergic reaction to the first DTaP dose, a high temperature following the DTaP, or any other severe reaction, including seizures.

Most doctors will postpone the shot for a baby who is significantly sick. Though a few doctors will also delay giving a DTaP (or other) shot because of a mild cold, this isn’t considered necessary—and could result in a child ending up incompletely immunized. After all, many babies who attend day care or who have an older sibling have frequent colds—sometimes one after another during “cold season.” Finding symptom-free windows of opportunity to vaccinate these babies according to schedule often proves impossible. Delaying shots because of mild fevers, ear infection, and most cases of gastrointestinal upset is also not usually considered necessary or wise.

Polio vaccine (IPV). Immunization has virtually eliminated polio (aka infantile paralysis), once a dreaded disease, from the United States. The oral vaccine (OPV), a live vaccine given by mouth, is no longer routinely given because it presented a minuscule risk of paralysis (about 1 in 8.7 million) in vaccinated children. Instead, it has been replaced by the inactivated vaccine (IPV), given by injection.

Children should receive four doses of IPV—the first, at two months; the second, at four months; the third at six to eighteen months; and the fourth, at four to six years—except in special circumstances (such as when traveling to countries where polio is still common, in which case the schedule may be stepped up).

The IPV is not known to produce any side effects except for a little soreness or redness at the site of the injection and the rare allergic reaction. The doctor will likely delay administering the IPV if your child is very ill. A child who had a severe allergic reaction to the first dose generally won’t be given subsequent doses.

Measles, mumps, rubella (MMR). Children get two doses of the MMR, the first between twelve and fifteen months, and the second between ages four and six (though it can be administered anytime as long as it is twenty-eight days after the first). Measles, though often joked about, is in reality a serious disease with sometimes severe, potentially fatal, complications. Rubella, also known as German measles, on the other hand, is often so mild that its symptoms are missed. But because it can cause birth defects in the fetus of an infected pregnant woman, immunization in early childhood is recommended—both to protect the future fetuses of girl babies and to reduce the risk of infected children exposing pregnant women, including their own mothers. Mumps rarely presents a serious problem in childhood, but because it can have severe consequences (such as sterility or deafness) in adulthood, early immunization is recommended.

Reactions to the MMR vaccine are generally very mild and don’t usually occur until a week or two after the shot. About 1 in 5 children will get a rash or slight fever lasting a few days from the measles component. About 1 in 7 will get a rash or some swelling of the neck glands, and 1 in 100, aching or swelling of the joints from the rubella component, sometimes as long as three weeks after the shot. Occasionally, there may be swelling of the salivary glands from the mumps component. Much less common are tingling, numbness, or pain in the hands and feet, all difficult to discern in infants, and allergic reactions. Large studies have not shown a link between the MMR vaccine and autism.

Caution should be taken in administering MMR to a child sick with anything but a mild cold, one with an impaired immune system (from medication, cancer, or another condition), one who has recently had a blood transfusion, one who has a severe allergy to gelatin or the antibiotic neomycin, or one who had a severe allergic reaction after the first dose of MMR.

Varicella vaccine (Var). Varicella, or chicken pox, until recently one of the most common childhood diseases, is usually a mild disease without serious side effects. There can be complications, however, such as Reye’s syndrome and bacterial infections (including group A strep); and the disease can be fatal to high-risk children, such as those with leukemia or immune deficiencies, or those whose mothers were infected with varicella just prior to delivery.

A single dose of varicella vaccine is recommended between twelve and eighteen months. A child who already had chicken pox does not need to get the vaccine. It appears that the vaccine prevents chicken pox in 70 to 90 percent of those who are vaccinated. The small percentage who do get chicken pox after receiving the vaccine usually get a much milder case than if they had not been immunized.

The varicella vaccine is very safe. Rarely, there may be redness or soreness at the site of the injection. Some children also get a mild rash (about five spots) a few weeks after being immunized.

Hemophilus Influenzae b vaccine (Hib). This vaccine is aimed at thwarting the deadly hemophilus influenzae b (Hib) bacteria (which has no relation to influenza, or “flu”) that is the cause of a wide range of very serious infections in infants and young children. Prior to the introduction of the vaccine, Hib was responsible for about 12,000 cases of meningitis in children in the United States annually (5 percent of them fatal) and for nearly all epiglottitis (a potentially fatal infection that obstructs the airways). It was also the leading cause of septicemia (blood infection), cellulitis (skin and connective tissue infection), osteomyelitis (bone infection), and pericarditis (heart membrane infection) in young children.

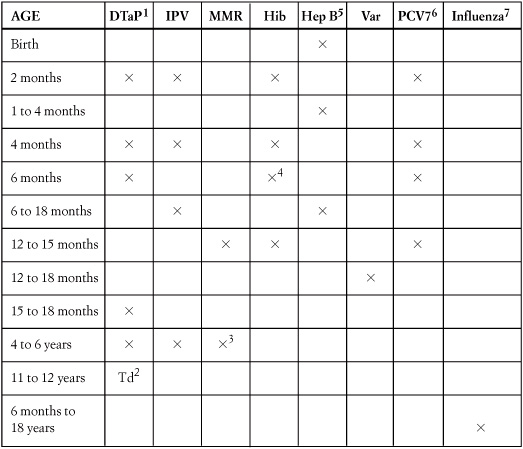

1. The fourth dose of DTaP should be given at least 6 months after the third dose. 2. Subsequent routine Td boosters are recommended every 10 years. 3. May be administered during any visit, provided at least 4 weeks have elapsed since the first dose and that both doses are administered beginning at or after age 12 months. 4. Three Hib conjugate vaccines are licensed for infant use. If PRP-OMP is administered at ages 2 and 4 months, a dose at age 6 months is not required. DTaP/Hib combination products should not be used for primary immunization in infants at ages 2, 4, or 6 months, but can be used as boosters following any Hib vaccine. 5. All infants should receive the first dose of hepatitis B vaccine soon after birth and before hospital discharge (unless the doctor plans on administering the Pediarix combo vaccine at 2 months). The first dose may also be given by age 2 months if the infant’s mother is hep B-negative. Infants born to hepB-positive mothers should receive hepatitis B vaccine and hep B immune globulin (HBIG) within 12 hours of birth, at separate sites. Hepatitis A vaccine is recommended for use in high-risk states and regions (all in the West), and for certain high-risk groups; consult your local public health authority. 6. It is also recommended for certain high-risk children age 24–59 months.7. Influenza vaccine is recommended annually for children over 6 months of age. Children younger than 9 years who are receiving the vaccine for the first time should receive two doses at least 4 weeks apart. Thimerosal has been removed from all vaccines with the exception of the influenza vaccine (which is available without thimerosal).

The Hib vaccine appears to have few, if any, side effects. A very small percentage of children may have fever, redness and/or tenderness on the site of the shot. Your child should get the Hib vaccine at two, four, and six months, with a fourth dose at twelve to fifteen months.

Though severe reactions to immunizations are exceedingly rare, you should call the doctor if your baby experiences any of the following within two days of the shot:

High fever (over 104°F)

High fever (over 104°F)

Crying that lasts longer than three hours

Crying that lasts longer than three hours

Seizures/convulsions (jerking or staring)—usually because of fever and not serious

Seizures/convulsions (jerking or staring)—usually because of fever and not serious

Seizures or major alterations in consciousness within seven days of shot

Seizures or major alterations in consciousness within seven days of shot

An allergic reaction (swelling of mouth, face, or throat; breathing difficulties; immediate rash)

An allergic reaction (swelling of mouth, face, or throat; breathing difficulties; immediate rash)

Listlessness, unresponsiveness, excessive sleepiness

Listlessness, unresponsiveness, excessive sleepiness

Should you note any of the above symptoms following an injection, call the doctor. This is not just for your baby’s sake, but also so that the doctor can report the response to the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System. Collection and evaluation of such information may help reduce future risks.

As with other vaccines, Hib vaccine should not be given to a child who is very ill (mild illness isn’t a problem), or who might be allergic to any of the components (check with the doctor).

Hepatitis vaccines. Hepatitis B (hep B), a chronic liver disease, can cause liver failure and liver cancer in future years. Three doses are needed. It is recommended that the vaccine for hepatitis B be given at birth (it may be delayed for premature infants), one to four months, and six to eighteen months. (If the Pediarix combo vaccine is administered, the doses are given at two, four, and six months instead.) Side effects—slight soreness and fussiness—are not common and are short-lived. The vaccine for hepatitis A (hep A), which also affects the liver, is recommended for children over age two living in high-risk states and countries, mostly in the western United States (check with your doctor to see if you are living in a high-risk area).

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7). The pneumococcus bacterium is a major cause of illness among children, responsible for some ear infections, meningitis, pneumonia, blood infections, and other illnesses. Though the PCV vaccine is one of the newer vaccines, large studies and clinical trials have shown that it is extremely effective in preventing the occurrence of certain types of ear infections, meningitis, pneumonia, and other related life-threatening infections. Children should get the vaccine at two, four, and six months, with a booster given at twelve to fifteen months. Side effects, such as low-grade fever or redness and tenderness at the injection site, are occasionally seen and are not harmful.

Influenza. The influenza, or “flu” vaccine is now recommended for all healthy babies between six and twenty-two months old. In the past, it was recommended that only young children at high risk for flu complications receive the vaccine. But studies indicate that even healthy children under age two are at increased risk for hospitalization from flu-related complications. The vaccine is especially important for those at high risk—those with serious heart or lung disease, those with depressed immune systems, asthma, HIV, diabetes, and those with sickle-cell anemia or similar blood diseases. The flu vaccine should not be given to anyone who has had a severe allergic reaction to eggs. High-risk children may, instead, be given antiviral medications to prevent development of influenza. When having your child immunized, ask for a thimerosal-free flu vaccine. (Flu Mist, the nasal spray flu vaccine, is not recommended for children under age five.)

If for some reason any of your baby’s vaccinations are postponed, immunization can pick up where it left off; starting over isn’t necessary. Work with the doctor to get your child caught up as soon as possible.

“I wash my daughter’s hair every day, but I still can’t seem to get rid of the flakes on her scalp.”

Don’t pack away those dark-shouldered outfits yet. Cradle cap, a seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp common in young infants, doesn’t doom your daughter to a lifetime of dandruff. Mild cradle cap, in which greasy surface scales appear on the scalp, often responds well to a brisk massage with mineral oil or petroleum jelly to loosen the scales, followed by a thorough shampoo to remove them and the oil. Tough cases, in which flaking is heavy and/or brownish patches and yellow crustiness are present, may benefit from the daily use of an antiseborrheic shampoo that contains sulfur salicylates, such as Sebulex (make sure you keep it out of baby’s eyes) after the oil treatment. (Some cases are aggravated by the use of such preparations. If your baby’s is, discontinue use and discuss this with the doctor.) Since cradle cap usually worsens when the scalp sweats, keeping it cool and dry may also help—so don’t put a hat on baby unless necessary (such as in the sun or when it’s cold outside), and then remove it when you’re indoors or in a heated car.

When cradle cap is severe, the seborrheic rash may spread to the face, neck, or buttocks. If this occurs, the doctor will probably prescribe a topical ointment.

Occasionally, cradle cap will persist through the first year—and in a few instances, long after a child has graduated from the cradle. Since the condition causes no discomfort and is therefore considered only a cosmetic problem, aggressive therapy (such as use of topical cortisone, which can contain the flaking for a period of time) isn’t usually recommended but is certainly worth discussing with your child’s doctor as a last resort.

“Our son’s feet seem to fold inward. Will they straighten out on their own?”

Your son’s not alone in his stance; most babies appear bowlegged and pigeon-toed. This happens for two reasons—one, because of the normal rotational curve in the legs of a newborn, and, two, because the cramped quarters in the uterus often force one or both feet into odd positions. When baby emerges at birth, after spending several months in that position, the feet are still bent or seem to turn inward.

In the months ahead, as your baby’s feet enjoy their out-of-utero freedom and as he learns to pull up, crawl, and then walk, his feet will begin straightening out. They almost always do so without treatment.

Just to be sure there isn’t another cause of your baby’s foot position, express your concerns at his next well-baby visit. The doctor probably has already checked your baby’s feet for abnormalities, but another check to put your mind at ease won’t hurt. It’s also routine for the doctor to keep an eye on the progress of a baby’s feet to make sure they straighten out as he grows—which they almost certainly will in your son’s case.

In the very unlikely event a baby’s feet don’t appear to be straightening out on their own, casting or special shoes may be recommended at a later date. At just what point treatment is considered will depends on the type of problem and on the doctor’s point of view.

“My son was born with undescended testicles. The doctor said that they would probably descend from the abdomen by the time he was a month or two old, but they haven’t yet.”