Georgia: First in Flight!

The story of Micajah Clark Dyer

by Jessica Phillips

AS THE CAR TURNED onto a dark paved road, the trees began to become bigger and fuller. To the left was a large field. To the right was access to Rattlesnake Mountain, from the peak of which Mr. Dyer flew his “flying machine.” Continuing down the road, we drove across a wooden bridge that was built over a crystalline creek. The trickling sound of the creek was calm and soothing. Just past the bridge, we saw Mrs. Sylvia Turnage’s house peeking through the trees.

As soon as I opened the door, Sylvia approached me with a smiling face and a welcome. Her house was filled with books, a testament to how much she valued knowledge. As we started the interview, you could immediately see her excitement about her great-great-grandfather, Micajah Clark Dyer.

Mrs. Sylvia Dyer Turnage is a local author who loves to record the heritage of Blairsville, Georgia. She started out writing poems, and she has now written several nonfiction publications. One thing that seems to stand out in most of her books is her great-great-grandfather’s story. Micajah Clark Dyer was the first to come up with the idea of what we now call the airplane. This fact shocks most people. I know what you’re thinking, “Didn’t the Wright brothers invent the first plane?” That is correct in that they invented the first gas-engine plane. But in the late 1800s, Clark’s ideas were so advanced, people thought he was crazy. Everyone said, “Why would humans need and want to fly?”

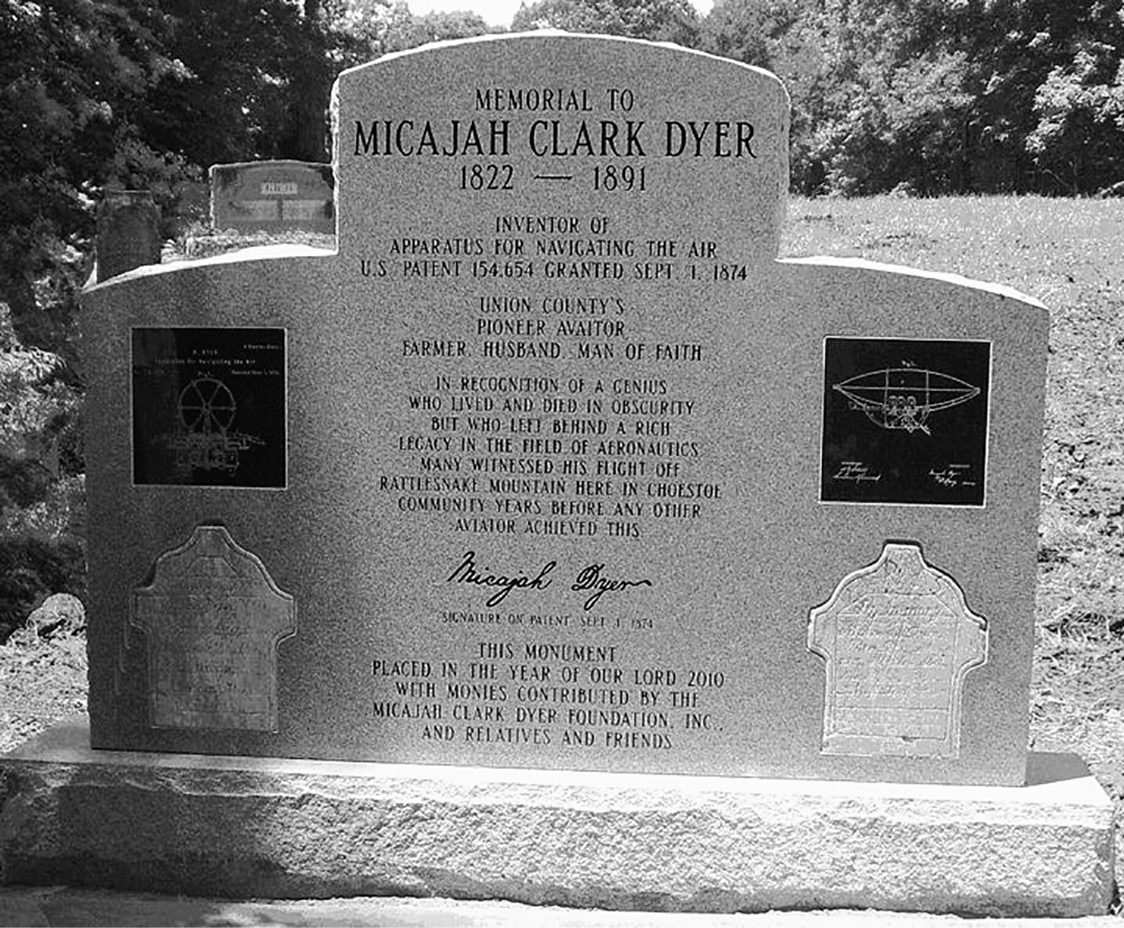

PLATE 23 The monument at Micajah Clark Dyer’s grave

Clark’s “flying machine” was somewhat different from planes we see today. It was made of wood in the shape of an oval. On the sides of the machine were protrusions that looked like oars on a ship. Attached to the top was a balloon that made it look something like a blimp. Sylvia believes her great-great-grandfather did not use this until later in his flying career.

“He was one of the pioneers that came over with his family when he was eleven years old, and they settled here in Choestoe. That was in 1832 or 1833. He is my great-great-grandfather. He was a farmer, of course. He was very much an inventor. He was always inventing things, even when he was very young. Of course, his greatest invention was his flying machine,” says Sylvia.

She goes on to say, “Kenny Akins, my nephew, teamed up with a guy name Bob Davis. They went all around and interviewed the old-timers. Several of the old-timers said, ‘Oh yeah, of course he did [build the first airplane].’ Kenny said, ‘Well, do you have anything written about it?’ The old-timers said, ‘No, nothing written.’ ” There were only three people who knew the story firsthand. Kenny said, “You know, I’m more convinced than ever that it happened.” He added, “Those people’s stories were consistent. They didn’t know we interviewed the other. It just has to be true.”

Sylvia wrote her first book about her great-great-grandfather “primarily because I said this story is going to be lost. The next few generations are not going to even know about it. That was like in 1994, I believe. Then, in 2006, my book was published. A lot of people saw it. A lot of the family was interested in the story after reading it. About twelve years later, I was sitting in church, and a distant cousin of mine and her husband were sitting beside me. He leaned over and said something about the patent for the flying machine.” She and her family had been looking for the patent for years with no luck, but her relative was insistent.

PLATE 24 Mrs. Turnage telling Jessica Phillips about Micajah Clark Dyer

“ ‘No. I’m telling you they found it. They found it,’ he repeated. I tell everybody you can guess how much I got out of the sermon that morning!” recalls Sylvia.

It turned out, she’d been looking for the wrong thing. “When Kenny and Bob were searching, they were searching for ‘airplane,’ ‘flying machine,’ ” but “of course, there was no such word as ‘airplane,’ ” she explains. Instead, it was patented as an “apparatus for navigating the air.”

After discovering the patents, Sylvia remembers, “We got to sayin’, ‘Well, we’ve got to have a model [of the airplane].’ I mean everybody was sayin’, ‘Well, what did it look like? What did it look like?’ Well, we had no pictures.” Sylvia says, “I was speaking to the Georgia Mountain Writers Club telling them about it. When I finished, a retired nurse who was just a pink lady at the hospital, that volunteers, came up to me. She wanted to buy one of the books. She said, ‘You know, I’ve got a neighbor who worked for Delta.’ She said, ‘He was a machinist there. He is just amazing and has done all kinds of models, especially of airplanes.’ She said, ‘Would you mind if I tell him?’ I said, ‘I would just be pleased. Tell him if he has any interest at all to call me.’ So she took her book over and left it with him and said, ‘This lady is looking for someone to build this machine.’ ”

The man called and asked what Sylvia had in mind. “What I would really like to see would be a model that was built to scale from his patent,” she told him. “He said, ‘Well, let’s get together and look at ’em.’ So, we did. I took the patent, and he sat down and looked at it. He said, ‘Let me think about it.’ In about two weeks, he said, ‘Let’s sit down again and talk about this.’ ” The man’s name was Jack Allen. Billy, Sylvia’s husband, asked how much it would cost to make a model of the plane. “I’m not going to charge you anything to do it,” replied Jack. “That is the most interesting thing I’ve come across lately.

“Georgia’s Pioneer Aviator Micajah Clark Dyer was finished and put in a display case. They have an exhibit in the old Union County Court House. Around the square in Blairsville, the historical society has a nice museum. I’m really pleased that they’ve got a real nice display for him. Our son-in-law did the first one, carved it by hand. So, the new model replaced his at the museum. We just moved that one and set up an exhibit in the Union County Public Library. Micajah Clark Dyer now has two places where a model of his plane is exhibited. You can also go online to www.micajahclarkdyer.org and look through the models and other things.”

PLATE 25 The model of Micajah Clark Dyer’s flying machine (from micajahclarkdyer.org)

“It was many years after his 1874 patent that the Wright brothers got their patent. I don’t think what he did in any way diminishes what they did, but it was a different era. They had a gasoline engine. If he had had a gasoline engine, I guarantee he would have been flying up and down the pastures,” says Sylvia.

“The flying machine did not have power, except he had paddles which he could catch wind with. What he would try to do was catch the updraft. He needed to get enough speed to come off the mountain and catch a draft, which would lift him.”

Dyer was evidently quite a character. “Everybody says his yard was just strewn with things that he was working on. He was always inventing something, lots of little things, you know. He ran water in his house, which nobody had running water in those days. There’s a spring up here, which we used also to supply water to our house for a long time. He hollowed out logs and piped the water into his house, so he was just always doing stuff that no one else was doing.

“There were eyewitnesses that saw Clark fly his flying machine, one whose grandmother saw the machine. She’s the last one I know of that has sort of at least a secondhand story. Her grandmother told her of coming up here, and he had a workshop that he kept locked. She looked through the gaps between the log walls and saw the machine.

“People made fun of the man, something terrible,” says Sylvia. “They thought he was crazy. Not everybody did, because he was also known as the genius. There was a bunch that called him a genius, but a lot of them said, ‘No, he is just crazy.’ Those ideas were just too far-out for his generation.”

But Dyer’s flights were observed by at least three of his friends: Johnny Wimpy, Hershel Dyer, and James Washington Lance. “They were the three that said, ‘Yes, we saw him fly it.’ It was their relatives, though, who passed the story down.

“I think that what he did was so important, the story needs to continue for generations to come,” says Sylvia. “It is important for the state, too, because North Carolina has all the credit. Like I say, it doesn’t diminish what [the Wrights] did, but they built on this. Some of the people we have talked to at the Smithsonian and the guy who was patent attorney there says it is important. I mean everybody who knows about such things say that it was a very important part of flying history.

“I think he could control it, which was what the whole purpose of the patent [was],” Sylvia continues. “They had the hot air balloons, but they didn’t have any control over them. The wind would crash them into things. So, he did this thing, and it was steerable.”

For years, Sylvia didn’t believe that any photos of her great-grandfather existed. “This lady called me up. She had read the book, and she said, ‘Do you have any pictures of Micajah Clark Dyer?’ I said, ‘No. I have looked everywhere for a picture.’ She said, ‘Well, you know I have a picture that has been hanging in my house. First it was in my grandmother’s house, then in my parents’ home, and I’ve got it hanging in my home now that is Micajah and Morena [his wife].’ ”

Sylvia is keen to see the local Blairsville airport renamed the Micajah Clark Dyer Airport. “I mean, they really should,” she argues. “I went forth before the mayor and the city council meeting, told them why they should name it that, sang the song for them, and they told me they were definitely going to do something for him at the airport. I don’t want just ‘something done.’ I want it named for him. They can do something. I mainly want them to name it for him.

“It is just a shame that there were no newspapers or cameras to record all of this,” she laments. “One of the guys who interviewed me said, ‘Oh, I don’t know. Then Clark wouldn’t have needed a great-great-granddaughter.’

“I would have probably climbed right in the flying machine with him and flew in it.”