Doctoring with Herbs

The story of Eve Miranda, Medicine Woman

A PERSON CAN LEARN A LOT riding with Eve Miranda down the two-lane roads of western North Carolina, zipping through three counties in less than three hours.

We were late—blame it on me—and Miranda was in a hurry to get to her son’s home in Macon County, then to Graham County to visit with two friends, and then back to Cherokee County before suppertime. She wasn’t speeding, she said—“I never get over sixty”—but she was steering her 1994 Ford Escort barely right of the centerline, maybe to smooth out the ride. “I like to drive in the middle of the road when nothing’s coming,” she said casually.

Miranda has been stopped by the law only one time, she said, but not for speeding. She never found out why the state patrolman pulled her over, because he left immediately after approaching her car. “Oh my god, ramps,” he said, obviously repulsed, as he spun around on his heels, got into his patrol car, and drove off.

She had been gathering ramps most of that spring day, leaving her and her car smelling like, well, ramps, which smell much like garlic. “People either love ramps or they hate them,” she said. The patrolman must’ve hated them.

Diminutive and dark-haired, Evelyn Martha Thompson Miranda, seventy-one years old, is a medicine woman. She goes to the woods and gathers herbs that are said to be useful in treating certain ailments and diseases. In the spring, she collects ramps, along with bloodroot, hepatica, and galm of Gilead. In the summer, she’ll look for mullein, joe-pye weed, pleurisy root, yarrow, and other herbs. In the fall, she climbs to higher elevations to dig ginseng, careful not to harvest the roots prematurely.

PLATE 26 Eve Miranda in her “sometimes” home

On the way to her son’s home, we talked about many things: herbs, of course, but also God, doctors, our purposes in life, serving people, her mother and father, her grandmother. Miranda even sang part of a favorite song, “Wayfaring Stranger,” at the insistence of her passenger.

Eve Miranda is not one for earthly possessions. She does not even have a house. You might say she’s homeless, although she prefers “without a permanent home.” She house-sits and pet-sits for people in or near her county. When she’s not looking after someone’s home, she sometimes stays at an old, two-story house just off the main street in Andrews, North Carolina. The house is being completely remodeled inside, and the owner often is out of town.

When she gets tired of being around people, or when she feels “used up,” she goes to meditate on a rock in the middle of a river and sleeps in her car for a night or two.

“When you’re a medicine person, sometimes you care so much about a person, it takes your strength,” she said later, following our ride through the countryside. “It takes your spirit, if you want to call it that. It’s like sitting at the bedside of someone you love. Eventually, you get used up.”

People around Andrews know Miranda is a medicine woman, and they come to her for advice. Sometimes they’ll see her car parked at McDonald’s and drop in to talk. But Miranda is careful how she doles out medical advice. She doesn’t want to be accused of practicing medicine without a license. So after hearing about a person’s ailments, she is likely to preface her response with “My grandmother would have done this.”

It was her grandmother, Florence Thompson, who lived in Quitman, Georgia, who taught Miranda the healing properties of certain herbs, starting when she was only six years old. Miranda’s parents owned a large farm in nearby Monticello, Florida, and her grandmother stayed with them a lot of the time. Now it’s time to pass on her knowledge of herbs to someone else. Miranda chose her daughter-in-law, Tracey Milton.

“A medicine woman,” she said, “has the opportunity to choose whom she passes the information on to. She has to feel something between her and that person, and that person has to be willing to be taught.”

Miranda has written numerous newspaper columns and magazine articles and published books on flowers, herbs, and Civil War recipes. She earns a little money speaking at seminars about herbs, gardens, edible plants, and trees, you name it. She sells plants she has gathered, but she gives away her concoctions and her advice because that’s what a medicine woman is supposed to do.

Miranda founded the Appalachian Heritage Alliance, an organization dedicated to the documentation and preservation of Appalachian history and culture, traditional and modern uses of native plants, and wild crafting. She has worked closely with the Revitalization of Traditional Cherokee Artisan Resources, gathering bloodroot for basket makers and teaching programs on dye plants.

The Bent Creek Institute, a research group for crop growers and botanical medicine developers and processors, dubbed her one of the most knowledgeable people in medicinal plants and featured her in its promotional video “Plants to People.” The list of honors, speaking engagements, and community involvement goes on.

And yet this woman is homeless. How could someone with such credentials end up without a permanent home? It happened suddenly. Miranda and her mother, Gladys Thompson, moved to Cherokee County permanently in 1995, following the death of Miranda’s father, Roy Thompson. Their first home was in Topton, on property that Miranda owned. But after a few years, she “bartered off the home” so that her son and daughter-in-law, Dan and Tracey Milton, could have land for a house. Miranda and her mother moved to Andrews and lived in the back of a store, which Miranda operated, selling watercolors, quilts, homemade soup, and “other stuff appropriate to the Appalachian way of life.” She wanted to be in town in case her mother needed a real doctor. But she never did, her daughter said. She wasn’t sick, “just wore out.”

PLATE 27 Dan and Tracey Milton in front of the home they built

After Miranda closed the shop, she and her mother rented a small house and lived there until Gladys Thompson died at the age of 105. That was in 2013.

“My mother died July tenth,” Miranda said, “and when I went to pay the rent on August third, they said they were going to have to double [it].” She refused to pay the new rate. “I was going to stand on principle,” she said, and decided she could live in her car for two or three months, until cold weather arrived.

Miranda admits she felt sorry for herself, at least for a while. “I took care of my husband. He died. I took care of my father. He died. My mother moved in, and I took care of her for twenty-one years. And she died. And I said, ‘Lord, I’ve been a good daughter and a good wife. I’ve tried to help my community, and I end up with nothing. How come I’m homeless?’ ”

One day, she drove to the Nantahala River and waded out to a large boulder. She just sat there. “A Bible verse that I had learned as a child kept coming to mind: ‘Be still and know that I am God.’ But I said, ‘Lord, speak to me in a voice I can understand and let me know what I am to do now. Show me.’

“Suddenly a fish jumped close enough to me to spray icy cold water against my face, and it was a wake-up call. I gazed at the river running past me. I had been coming to that same spot in the river for many years, as had my mother and grandmother, and it dawned on me that for twenty-four hours a day, month after month, year after year, decades after decades, centuries after centuries, thousands of years, that river had been running by that rock without my help, and everything began to fall in place.”

As Miranda saw it, God was telling her that everything has its time and place on earth, she said, and it was up to her to do something with hers. She gave thanks for the people in her life who quoted scripture to her, hoping that she would follow in their footsteps and go about doing good. Half of all healing, her grandmother had told her, was “being of good cheer, sharing and caring, showing compassion, not taking illness into your heart and soul, and not being a selfish speck.”

Her purpose in life, she figured, was not just to gather and prepare her medicines, but also to share her knowledge with others.

“Eve is unique,” said Judy Johnson of Andrews, who has known Miranda for nine or ten years and accompanied her on forays into the woods to photograph plants and herbs. “She is one of the most caring people I’ve ever come across. She tries to help people in different ways. She’s good at networking and putting people together who can help each other. That was one of the first things that I noticed about her. She’s very community minded.”

As an example, Johnson mentioned Miranda’s work at the community center in Topton that she kept going, where she helped older people stay busy and useful. She’s always willing to help, but don’t assume that she will march to anybody else’s drumbeat, Johnson said. She has found her own.

By the time we arrived at her son’s home in Macon County, Dan Milton had closed the gate that protects his place, located on a little hill in the Nantahala Community. “Dan knows I’m never late for anything,” Miranda said.

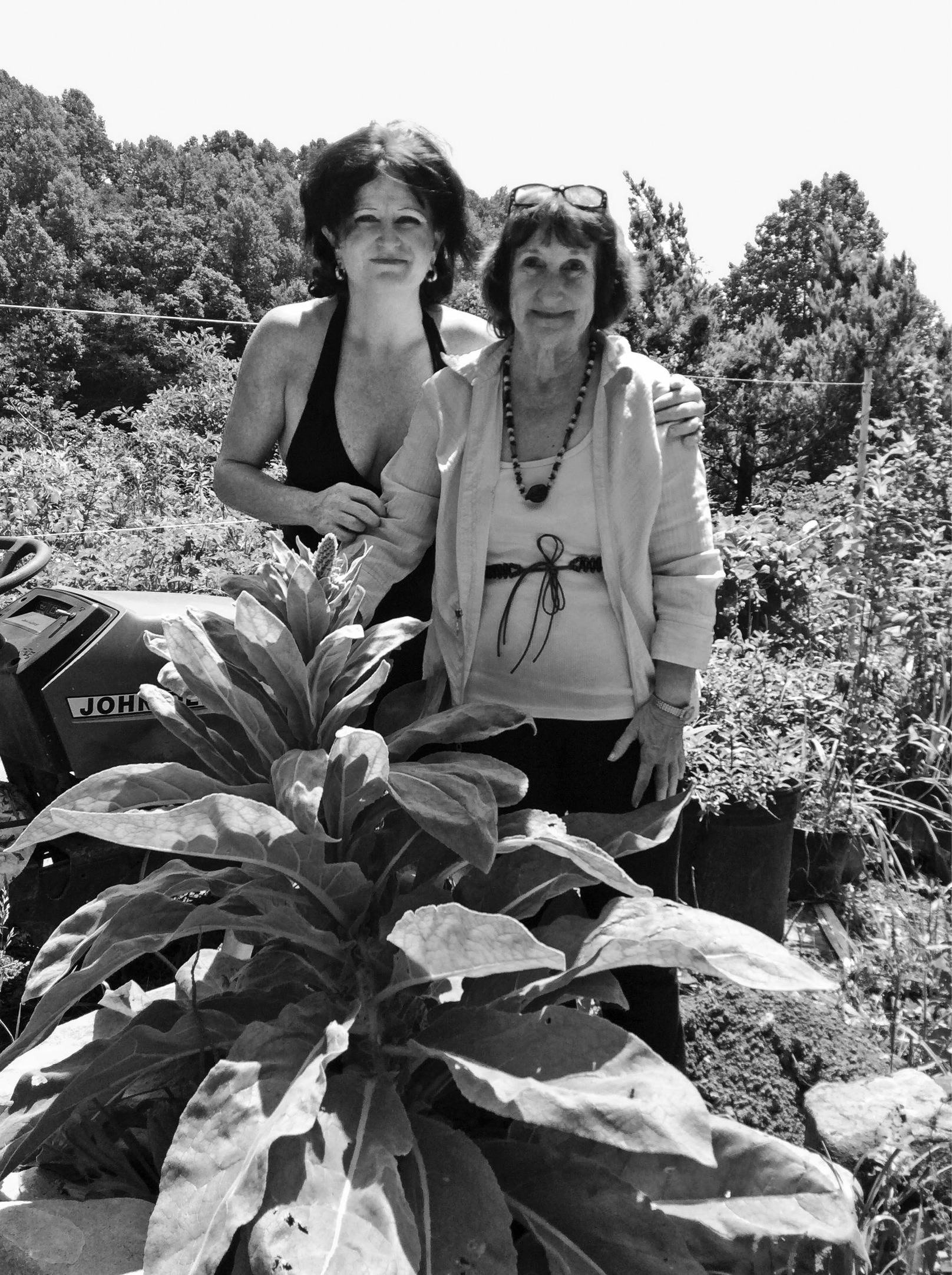

PLATE 28 Eve Miranda and daughter-in-law Tracey Milton show off a crop of mullein growing in the Miltons’ yard.

We stayed only a few minutes, long enough to take several photographs and to listen to Milton talk about how a wad of wet yarrow had stopped his bleeding after a hay thatcher punctured his arm all the way through. His wife, Tracey, posed for photos with Miranda, both holding different herbs growing in the Miltons’ yard.

For the past fifteen years, Tracey has been helping her mother-in-law research the usefulness of herbs, try out new concoctions, and compile data. She’s also been reading and studying herbs on her own. Miranda said she’ll be a good medicine woman.

Soon it was time to mount Miranda’s Ford Escort and head off across the ridge to Pinhook Road in Graham County, near Robbinsville, where we met Bob and Carol Lawson at their home. They had fled a hurried and harried life in California and settled down in picturesque North Carolina.

To no one’s surprise, the Lawsons have herbs and interesting plants growing on their property, including the service berry, or sarvis berry, as it’s sometimes called in the mountains. “When it bloomed,” Miranda explained, “it meant the ground was no longer going to freeze hard, and you could bury your dead.”

PLATE 29 Bob and Carol Lawson with a pawpaw tree

Standing stately in a neat row at the Lawsons’ place are several pawpaw trees, which produce a fruit used in jellies and pies and even for making wine. Before he moved here, though, everything Bob Lawson knew about pawpaws came from the children’s song that goes, “Pickin’ up pawpaws, put ’em in a basket.”

The Lawsons, along with Miranda, were instrumental in starting the Smoky Mountain Native Plants Association, and Miranda also helped form the Cherokee Native Plant Association. The three of them helped to produce what Miranda calls “the only ramps product in the US.” It’s a locally grown and ground corn made into meal and infused with dried, powdered ramps. The state patrolman who pulled Miranda over probably wouldn’t like it.

After taking a few photographs at the Lawson place, we were on our way back to Andrews, scheduled to arrive by five thirty. We were on time. “I am never late,” Miranda reminded her passenger.

It had been a day of adventure and learning. But one question remained: Where does a person who owns no property gather herbs and plants without breaking the law or getting shot by an angry landowner? Well, some landowners are generous and understanding, Miranda said, and they allow her to gather. She also has friends in forestry and in plant research such as at the Bent Creek Institute, which allows her to gather plants for study.

“The government is making it harder for gatherers,” she said. “They say ramps are getting scarce, but they’re not. Restrictions play a large part, but if you have a permit or you’re on private land, you can still gather.” True gatherers, she said, know what they’re doing, and they respect the land.

Miranda has no plans to stop. Her grandmother no doubt would have been proud of her. Florence Thompson taught her granddaughter all about herbs: how to identify them, how and when to harvest them, how to use them. To help the child with gathering, Thompson folded up the bottom of one of her large aprons and sewed the sides, closing it off to form a pouch for the herbs. Then she would tie the apron around young Miranda’s waist.

For herself, Miranda’s grandmother attached a large sash to a croker sack or burlap bag and slung it across her shoulders. They each carried paper sacks with the names of the plants they were looking for. The two set out and gathered first the hard-to-harvest materials, those with deep roots. “If we gathered those later in the day,” Miranda said, “it would be much harder, energy wise, to harvest.”

Eve Miranda has gone “from rags to riches and back to rags,” as she put it, but she wants no pity. “I am perfectly happy,” she said. “You don’t have to be somebody or have a lot of money to be happy.”

She has no earthly home. But she has herbs to gather, workshops and festivals to plan, roads to travel, dances to dance, and songs to sing. She sings somewhere around Andrews practically every Saturday night. She wants to help establish gardens using native plants and pass on her knowledge about herbs to her designated medicine woman. She wants to stay busy.

Today, she’s looking at the end of her life, not the beginning. “Okay,” she said, referring to herself, “you got ten good years left, fifteen good years left. What are you going to do with your life?”

It appears she’s already doing it.

SEVEN IMPORTANT HERBS

Miranda and her grandmother looked for all kinds of herbs, but here we’ve narrowed the list down to seven that Miranda still harvests, or purchases.

Pleurisy root: “This brightly orange-flowered plant with roots resting in China was the first on the list,” one that she created. “It is commonly called butterfly weed because it attracts large swallowtail butterflies. Many times, this root was mixed with other herbs for people with deep-seated wet coughs, lung problems, or pneumonia. It seemed to help get the phlegm up and out. Since harvesting kills the entire plant, I now buy it in bulk from a commercial grower instead of digging it.”

Joe-pye weed: “One of my favorite plants to gather was joe-pye weed, or queen of the meadow. While Grandma was digging the roots, I would use the hollow stems to drink water from a nearby creek, or later in the day, when it was hot, I would jump into the creek, into a deep spot, and breathe through it, hiding my body completely under the water. Of course, Grandma just watched for the stem, knowing where I was hiding at any given time.

“We would dry the root, which looked like a person with a bad-hair day, its many parts spangling out in all directions. Then we would dice it up or string it out. And for anyone with gravel or kidney stones, [my grandmother] would make a tea to be drunk until the person found relief.”

Yarrow: “One of the most lifesaving and useful of herbs is the yarrow. Just read about Achilles, the great man of war, who insisted that all his soldiers carry a medicine bag filled with yarrow into any battle. He gave away his last amount to a young soldier who had none. [Achilles] was nicked on the heel and bled to death, when, if he had had his usual pouch of yarrow, he could have staunched the flow of blood until his medic arrived. Yarrow also has been used by patients with hepatitis C and those with liver problems.”

Bloodroot: “Cancer was not so prevalent in Grandmother’s day, but I remember that she used a combination of bloodroot, sheep sorrel, comfrey, and other herbs to treat external cancers. The mixture created a black salve that appeared to draw cancers out by the root.”

Wild yam root: “The most called-for these days is wild yam root. I, again, use this root in bulk powder form, filling capsules with the exact amount needed, for folks with acid reflux, babies with colic, and many cold sores and fever-blister cases.”

Jewelweed: “For anything that itches, including poison ivy, the jewelweed or touch-me-not is the best there is. The inside of the lush stalk in early summer soothes the rash and seems to stop the eruption in its tracks. We also harvest the seed for making cookies in the fall. They taste a little like walnuts.”

Plantain: “This is another plant that is high on any gatherer’s list. While tramping through the forests, one is often stung by yellow jackets or wasps or ants, and nothing stops the pain better than your own saliva and plantain. When stung, we just put a wad of plantain in our mouths, chewed it up and put the juice and wad on the bite. Instantly the pain is gone, and usually no swelling occurs.”