How to Turn Junk into Art

An interview with Jane Taylor

JANE TAYLOR is a folk artist. She finds sad, useless pieces of iron and other metals and welds them together to create whatever that overactive, artistic mind of hers can envision. If she somehow sees a cow in a rusty piece of iron, it will be an iron cow when she’s done. If it’s a philodendron, those farm-tractor seats she’s working with will soon become the hardy leaves of a philodendron. And Taylor is multitalented. She paints. She does interior and landscape designs. But, she says, “I think I will always work with metal.”

This petite woman with the pixie cut and perky personality looks like anything but a welder of dirty, rusty, unusable pieces of iron. Still, the evidence is there, some of it standing tall and imposing, some of it “itty-bitty,” as she puts it. She welds when it’s ninety-plus degrees; she welds when it’s freezing outside.

Taylor says she loves art. “I breathe it,” she says. But it hasn’t always been that way. Her passion only came after many unsatisfying years in more commonplace lines of work.

Jane Elizabeth Taylor—no, she wasn’t named after the actress Elizabeth Taylor—was born on June 8, 1961, in Gainesville, Georgia, to Nesta and J. Verlon “Bo” Taylor. Jane’s father was a dentist, a man serious about his work and equally serious about everything else. That’s the way he wanted his young daughter to be, serious. So, after high school, Taylor worked in her father’s dental office, then in a physician’s office, and in a clothing store in Macon, Georgia. “I was very serious most of my life,” she says. “Very serious. I was brought up that way. You don’t play. I was good at what I did, but I never really enjoyed it.”

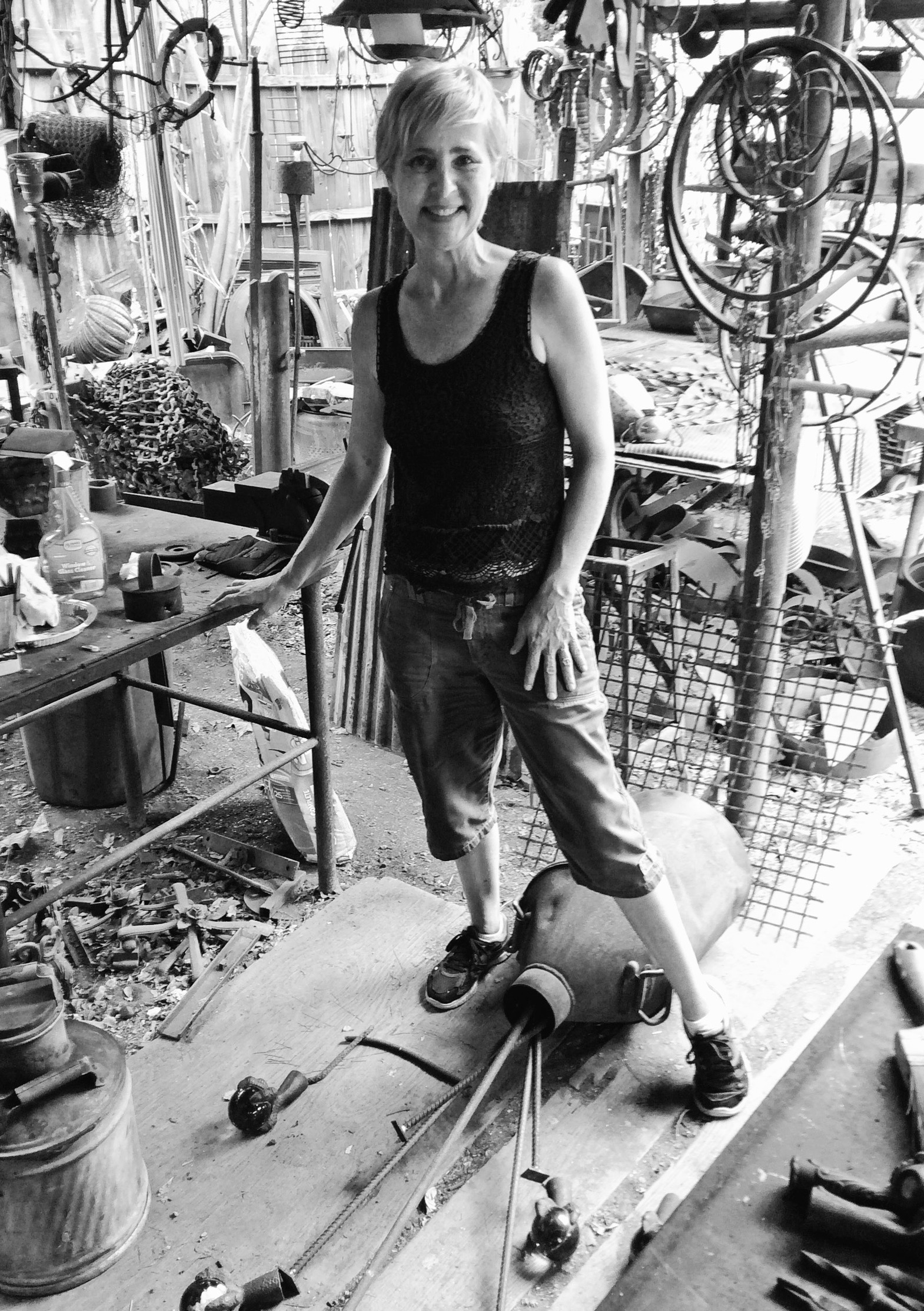

PLATE 33 Jane Taylor, artist at heart

One day, with enough money saved to carry her for six months, Taylor quit her job and set out to find her calling, or at least something more fulfilling. A friend talked her into getting into the antiques business with him. She went to auctions, bought antiques, and put them in the store. Within a week, they had sold. She filled up her space the next week, and everything sold again. The antiques partnership lasted about a year. But she didn’t like not knowing the people who were buying from her. She wanted her own shop.

“So then this place became available,” she says, referring to her present cottage and property, which, at one time, had been used to store tractors for a farm-equipment dealership next door.

By 1997, Jane Taylor was in business for herself, owner of a small house and display area on Cleveland Highway, about two miles from downtown Gainesville. But babysitting antiques wasn’t her thing either. “I got bored selling antiques very quickly,” she says.

But while looking for new stock, “I would go to auctions and see gorgeous iron, broken, sad, beautiful,” she says. “It was all hand-forged. But no one bought these pieces, so I bought them, anything that was interesting. At that moment, I fell in love with iron.”

PLATE 34 The cottage

At first, she enlisted professional welders to execute her vision, but nothing came back exactly the way she envisioned it. The welders would add their own little touches.

One day, her father, the man who was known for his seriousness, said to her, “Why don’t you do it yourself?” Why not? If she did her own welding, she could create exactly what she wanted. Just go to Lowe’s, buy a welder, and start welding. What could possibly go wrong?

For one thing, self-taught welders burn themselves a lot, even after they’ve read the directions carefully. Finally, though, Taylor started to catch on.

“Then,” she says, smiling, “the artistic side of me came out. I’d wake up in the morning: ‘I must build the Statue of Liberty today.’ ” Of course, she didn’t build her scrap metal reproduction of the Statue of Liberty in a day, but in her mind, it was a finished piece, even if it took six months to complete. Once built, her Statue of Liberty stood about fifteen feet tall, solidly constructed out of sheet metal, stove parts, cobbler’s shoe molds, shovel heads, and, for the torch, a discarded light fixture illuminated by a dusk-to-dawn solar-powered tiki light.

PLATE 35 Statue of Liberty

“I think every artist has a muse, somebody that comes to you and tells you what to do next, tells you what direction to go,” says Anne Brodie Hill, a painter and a friend who gets inspiration for her own art every time she visits Taylor’s place. “I don’t know what kind of muse she has, but a lot of the things she does, like her paintings she’s doing now, I don’t know where that comes from. She’s either got a new muse, or the old one got tired of working with rusty stuff.”

Taylor’s old muse is still there, ready to nudge her along when she’s ready. It’s just that right now, for the last few weeks, she’s wanted to paint, and she’s been turning out abstracts and paintings of cats and other characters.

“The other night,” she says, “the person I painted, I painted over it because she looked so sad. You can’t hide your feelings in your art.” If you ask Taylor about her favorite pieces, she says quickly, “Oh, gosh, they’re all my favorites. Then when it’s placed in a home, it becomes special. It stands in a perfect spot.”

“The figures probably are favorites,” she says, “because they develop a personality.”

Everything at Taylor’s studio is for sale, everything except the seven-foot-tall angel Marguerite, named for her grandmother, Marguerite Marie Hine, which stands on the cottage’s roof, directly over the office; and an old cash register on her desk that came from a traveling side show. She found that in her dad’s garage.

Even the pieces she has taken home for her own enjoyment can be bought, but she admits that she creates art more for her pleasure than for money, not always a good idea if you’re trying to make a living. Taylor says she doesn’t promote herself as well as she should. “The more arty I have become, the less businesslike I have become,” she says. “It trumps that side of my brain. I should be online and have a website, but I have a Facebook page. It must be something about my insecurity as a person. A lot of artists are like that. That’s why we’re all broke. We don’t market ourselves because we’d rather make our art.”

PLATE 36 Jane with her angel wings

Still, Jane Taylor is one of the top-selling exhibitors at the Quinlan Visual Arts Center in Gainesville. Amanda McClure, the executive director, says, “She looks at the world with a perspective all her own, and we are fortunate that she shares this with us.”

Making art, after all, is both Taylor’s vocation and her avocation. She turns out whimsical works that coax a smile or even a laugh from visitors. She makes refined pieces, such as towering doors and wings and candelabras. And then there are the just plain interesting items that might require a little imagination from the viewer.

Commissioned by an anonymous donor, she built a pair of angel wings to adorn the North Tower entrance to the Northeast Georgia Medical Center in Gainesville. The wings, nearly twelve feet tall, are made of found and sheet metal.

Taylor sees beauty and possibility in some of the strangest objects. Her cramped office offers perfect specimens. There’s a spiraling, tapering piece of metal that was used to stir grain in a silo. There’s a wheel spacer from a tractor trailer and a set of scales for weighing cotton. There’s a chain designed to move feed along in a chicken house. All of these are just waiting to be transformed, like the pipe cutter she turned into a lamp and the angel gleaned from a four-legged Victorian table.

“I just love her angels,” says Valerie Kirves, a friend, who has three of them in her home. “I saw those, and I couldn’t let them go anywhere else.”

Kirves owns a furniture/art business that specializes in iron and metals, and she sometimes takes broken pieces of iron and other metals to Taylor. “I’d be so excited to go back and see what she had created from the broken pieces,” she says. “I can’t even imagine putting stuff together like she does. She is just so tremendously talented. She’s just a really good, bighearted person, and all of her work comes from her heart.”

Besides metal that people donate, Taylor regularly scouts around for “strays,” as she calls them. While her other strays—three cats—are allowed to hang around the shop, stray metal is transformed into art and eventually moves on. And to Taylor, it’s all play, no work.

“My mother is aghast at what I do,” she says. “She’s proud of me, but she’s amazed. She doesn’t know where it came from. But she looks at my little hands and cries.” Taylor says her hands are marred by calluses, burns, and cuts, and she holds them out to prove it.

Taylor is unpretentious and honest, humble, in fact. For years, she drove a 1973 Ford Ranger she called Zelda, which she equipped with wrought iron cemetery fencing for its truck-bed railing. She refuses to copy others’ art. “If I can’t think of something myself,” she says, “I shouldn’t be doing this.” In describing her folk art, she eschews fancy terms. “I mean, I’m in vogue now,” she says a bit sarcastically. “I was doing this twenty years ago, and now it’s repurposing. The new one is upcycling. I’m just a recycler.”

PLATE 37 Jane dressed for work

Whatever you call it, Taylor makes it work. She can turn a dome that covered food in an upscale restaurant into a lovely chandelier, and tarnished cream pitchers into shades for light bulbs. She welds and hatches a bigger-than-life bird from stray parts. She makes three-dimensional Christmas ornaments from sardine cans and trinkets.

Behind her cottage and display yard is a fenced-off area that contains hundreds of metal pieces of all shapes and sizes, along with a shed that houses Taylor’s welding station. She’s now trying to incorporate paint into her metalwork. “I’m not sure how that will work,” she says, but she’ll give it a try. And when she succeeds, which is often, she inspires other artists.

“Every time I go over there, I see something I want to paint,” says Anne Brodie Hill. “I want to take a photograph of what she has set up, and I want to do a painting of it because it’s just so cool. As an artist, I’m kind of an abstract realist, if there is such a thing. I like to do layered paintings of the kind of stuff that she makes. She and I did a collaboration one time, and I’ve never had so much fun, because of her inspiration. She made me look at old, rusty junk differently.” Exhibiting together, Brodie and Taylor called themselves “the Twisted Sisters,” taking their cue from the heavy metal band Twisted Sister.

PLATE 38 Junk for future art

There was once something twisted, Taylor says, about the cottage where she set up shop twenty years ago. The back-left room was, well, a little strange. Taylor and her father painted the room white, perhaps subconsciously trying to sanitize the space. All the pieces Taylor chose for the room were also white. But nothing sold. Nothing. “People would go in the room, and they’d walk right back out,” she says.

Taylor had a morning routine for every room in the cottage. She would turn on the lights and a fan and move to the next room. But the lights in the back-left room would flicker off, and the fan would turn itself off. Taylor and her dad avoided the room as much as possible. “Dad didn’t like that room.”

One day, “this very bohemian woman comes in,” Taylor says, “and she’s looking around. And she tears out of the store. I went out on the porch and said, ‘Are you okay?’ And she said, ‘You’re going to think I’m strange, but I see auras, I see energy, and that back-left room has a big ball of pulsating evil.’ ” The woman told Taylor what to do to get rid of the evil. You’ll have to do it yourself, the woman said, because it’s your space.

PLATE 39 Jane with an unfinished project

Jane Taylor felt a little silly, but she prepared to do exactly what the woman instructed. “It was all kind of comical to me,” she remembers. “I took it all with a grain of salt. But there was a little part of me that believed, you know?”

The woman gave Taylor a small sage brush tied with hemp and explained the ritual. On a night when the moon was full, Taylor placed a small candle on a table in the center of the room. She lit the sage with a match, extinguished the blaze, and then smudged the room’s walls with the smoky brush. She stepped into the doorway and prayed, “This is my space. In the name of Jesus, please leave this house.”

Suddenly, she recalls, the flame shot up from the candle and splayed on the ceiling. “I dropped everything, the sage brush, and ran out of the room,” Taylor says, her voice lowering. “Whew! It was a terrifying experience.” The woman came back later to see what had happened. She walked into the back-left room, and when she came out, she said, “You did a good job.” “I haven’t seen the woman since,” Taylor says.

She did hear that several decades ago, five men wanted by the law had holed up in the house, and one or two of them died in a shoot-out with officers. It all made sense, she says.

PLATE 40 Tractor seats become flowers.

A couple of days earlier, Taylor’s mother, the coolest mom in the world, her daughter says, texted her about the interview for this story. “Does he understand you?” she asked, referring to me, the interviewer. “Are you projecting what you want him to see?”

Taylor texted back: “I don’t know, Mom. I am a work in progress, and I learn something new every day. My biggest delight is making people happy. And hopefully I will evolve into an artist who is at peace with her work, finally. It’s a battle I go through every day.”

PLATE 41 Jane’s art

Her friends and customers will tell you that Jane Taylor should be at peace with her work. Whether she realizes it, she is an artist in the truest sense of the word.

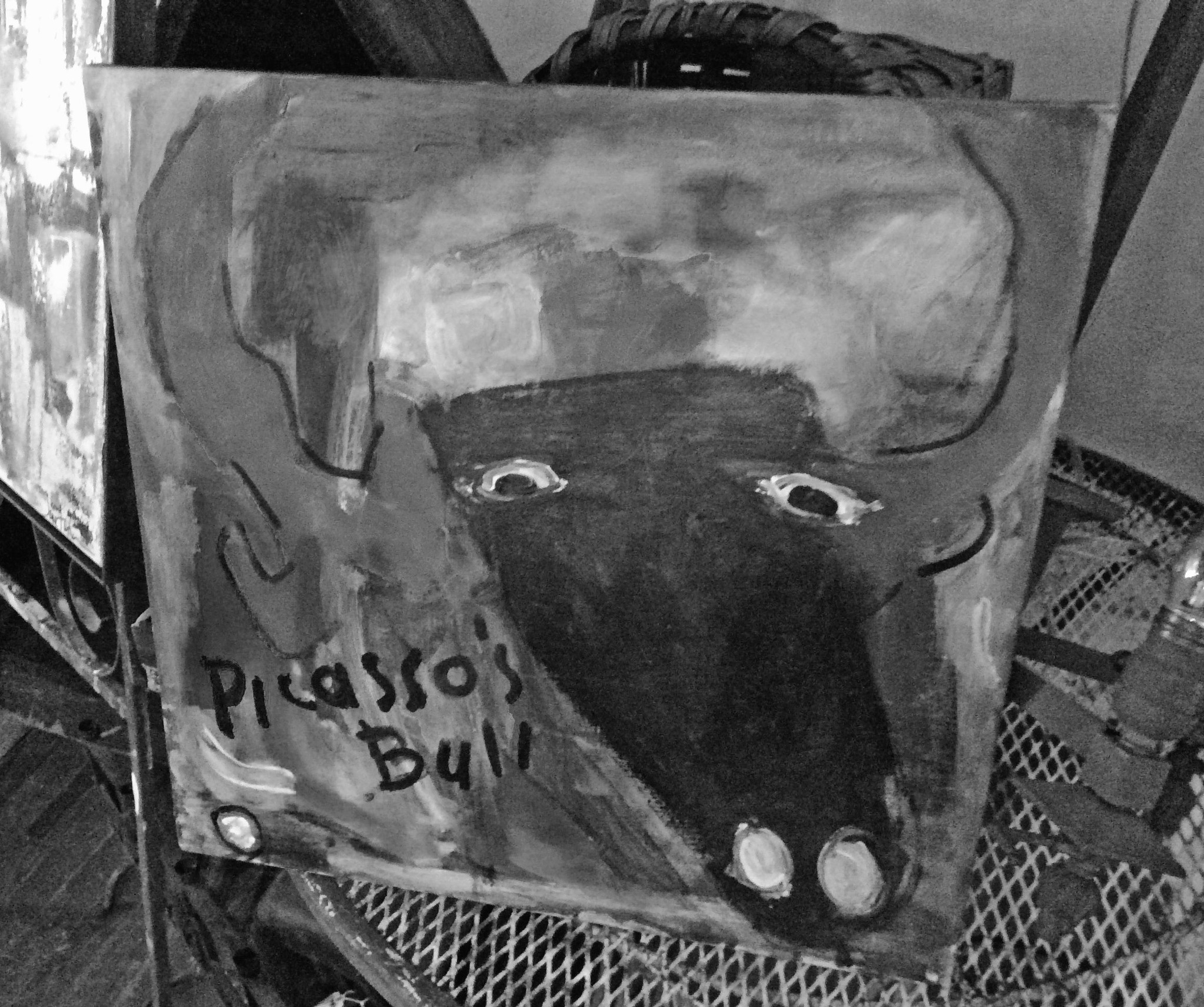

PLATE 42 Jane’s first abstract

PLATE 43 Picasso’s Bull