Keeping the Land and the History

Stories from Wayne County, Kentucky

IT’S A WARM, RAINY AFTERNOON in early May, close to suppertime, and Carl Foster isn’t expecting company. He doesn’t have email or a telephone, so I couldn’t contact him about an interview. I just took a chance that Foster would be willing to sit down and talk, and popped in.

Foster lives about seven miles down Freedom Road, which starts a few miles from Monticello, Kentucky, and fades from blacktop to dirt and gravel. The road meanders through Denney’s Gap, crosses a little bridge over a creek, and winds up in the Freedom Community. Freedom Church is just down the road, maybe two hundred yards from the Foster place, and the old Freedom School, when it existed, was about a mile away.

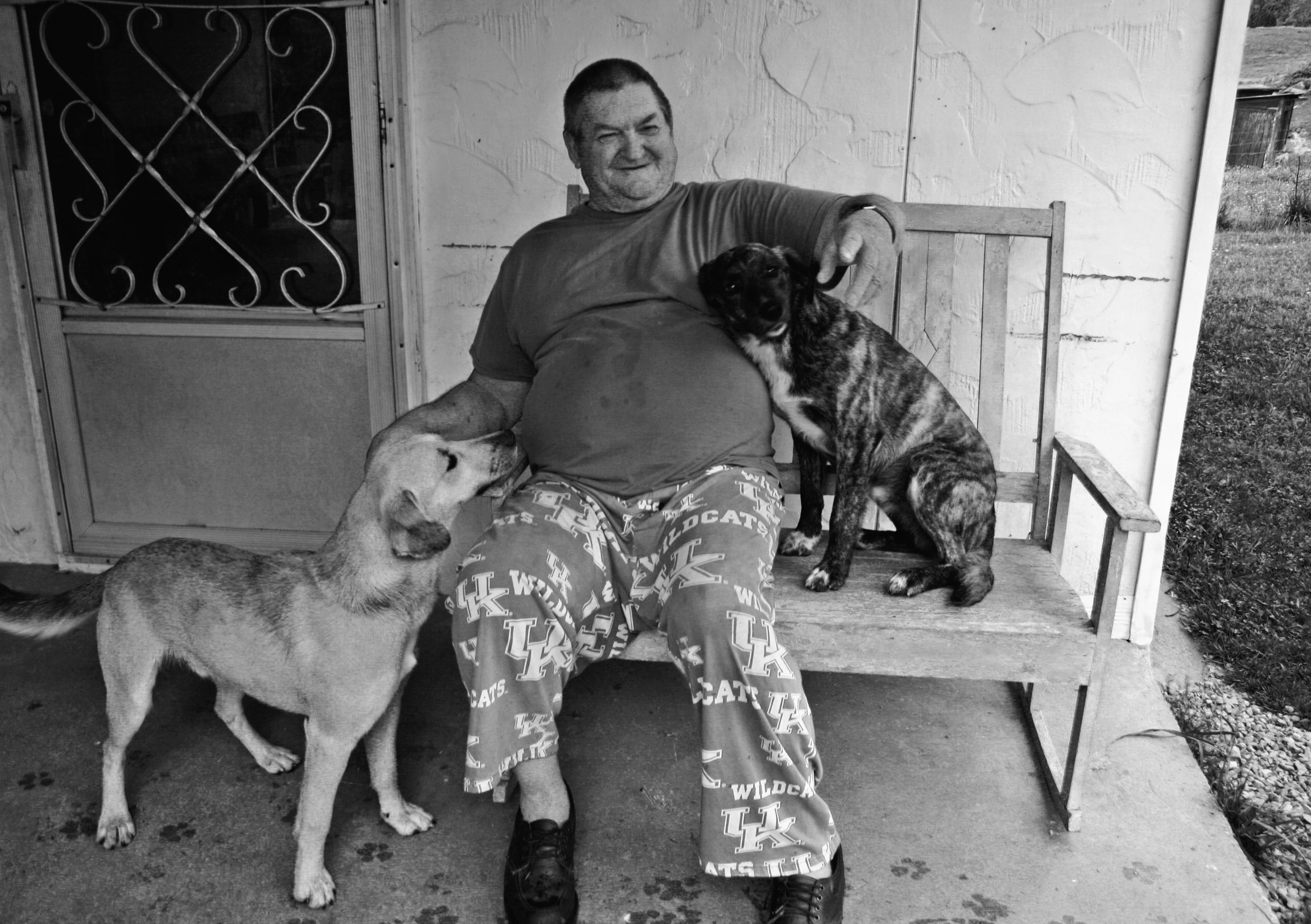

Foster is dressed in a T-shirt and blue pajama bottoms covered with University of Kentucky Wildcats logos. Laid-back and friendly, he sits at his kitchen table and talks as though he’s known me all his life.

His dogs, Rusty and Frank, are eating on the front porch. They’re brothers and a three-way cross: a quarter beagle, a quarter Australian shepherd, and half cur.

Foster has hunted ever since he was big enough to carry a rifle or shotgun, and he still hunts today. But now he usually drives a Gator four-wheeler, following Rusty’s and Frank’s barks in their search for quarry.

“I’m doing pretty good to be as old as I am,” says Carl, who was born April 23, 1948. He has a little trouble with diabetes, and something that broke loose in one of his eyes is “floating around like a fly in Jell-O. Doctor said he couldn’t do a thing for it.”

PLATE 59 Rusty and Frank, Carl’s dogs of questionable heritage, eat well while the master’s around.

While we are talking at the kitchen table, a young man drops by to return a set of chains he borrowed to pull a Jeep that had broken down near the Little South Fork of the Cumberland River, on down Freedom Road a piece. He wanted to use Foster’s phone to call for help but settled for the chains. Foster doesn’t have a phone, because he didn’t make but a couple of calls a month, he says, “and I’m not going to pay them thirty-six dollars a month for two phone calls. Other people would call me, but now they can’t. If something happened, like a doctor wanted to raise my insulin, now he’ll have to send me a postcard.” He laughs.

Foster voluntarily repeated the eighth grade at Freedom School because state law said he couldn’t drop out until he was sixteen. He reached the required age and quit. High school was just too far to walk. “You had to get up, say, at four o’clock and walk four miles to catch the bus to Monticello,” he says.

Besides farming, Foster has done a little of everything to make money. He worked for a Monticello plant that made wood parts for cabinets; he was a night watchman for a coal company; he even went to Indiana to work for a while, first in a rock quarry and then at a factory that made televisions.

PLATE 60 Carl Foster

“I never liked Indiana,” he says, a frown replacing his friendly smile. “You can’t see nothin’. You could see as far as you could, but you couldn’t see nothin’.”

A coal company official tried to persuade him to come to Perry County, Kentucky, to work in a deep mine. “No way am I going underground,” Foster told him.

Foster has lived alone since his mother died. He never married. “No, I never thought about it,” he says. “I had too many bosses the way it was: Dad and Mom and then at work, and the older brothers would tell you what to do when you went out to the farm. I didn’t need another boss.”

These days, he says, he mainly piddles around the farm. He feeds the heifers that are calving, and he turns the chickens out to let them scratch around freely. He keeps them put up at night to prevent the coyotes from killing them. He’ll bust wood for his stove for about two hours, take a nap, and get up and make supper. Then it’s time to sit back and read or watch television.

Foster’s needs are few, and he’s content, you can tell, as he walks around in his yard, stopping occasionally to talk about Freedom Community or to pose for a photograph in front of his small, white frame house with an American flag attached to the fascia board waving in a rainy breeze. Foster and each of his seven siblings were born in that little house.

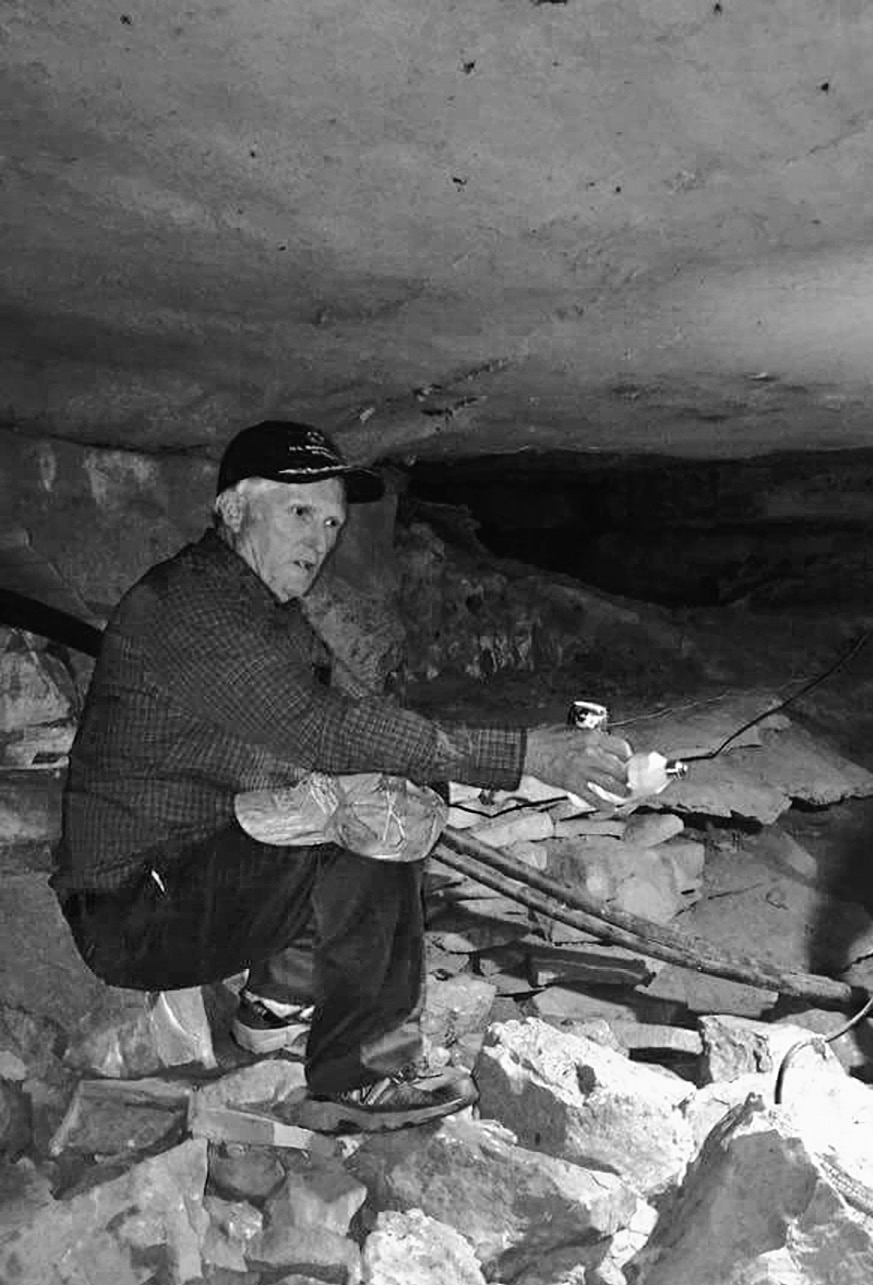

Behind the Foster home is some of the prettiest Kentucky pastureland in the region, along with a cave where family members kept their perishable foods before electricity made its way into the remote community. This land has been in the Foster family since 1915, when grandfather Allen Foster bought about 165 acres from Henry Phillips. He built the present house in 1927, and Carl’s daddy, Raymond, remodeled it in 1975.

It’s later in the evening, and the rain has stopped. The temperature is pleasant enough for sitting out on the front porch at Carl’s brother Boyd’s place, situated on about seventy-five acres, four miles or so from Carl and the old homestead. Boyd; his wife, Helen; and son Gerald, just like Carl, are friendly and welcoming, and they invite me to sit a spell.

PLATE 61 Boyd Foster sits inside the cave where family kept perishable food.

Carl and Boyd purchased their siblings’ parts of the Foster land after their parents died: their father in 1987 and mother in 2008. “If you put land up or a homeplace up in a public auction,” Boyd Foster says in a later conversation, “you don’t know if somebody is going to outbid you.” Together, they own 182 acres in one tract around the old Foster home. And with adjoining land that they own with Boyd’s sons, the Fosters can claim about 382 acres in the Freedom Community.

Keeping land in the family is important not only to the Fosters, but to others in Wayne County. Members of another family in the county even intermarried, marrying cousins, to keep their land.

What makes the Foster land special? Says Boyd: “Well, it’s my homeplace, first off. I was born and raised out there. The only time I left this country was when I pulled a tour in the United States Marine Corps and went to Vietnam. We’ve lived here and never had any trouble with people bothering any of our stuff. And that’s something to be thankful for.”

Boyd was drafted into the Army and went first to Louisville, Kentucky. But the Marine Corps sent word that it needed two good men to fill out a platoon. He was one of those two good men. “First letter we got,” Carl says, “he was in the dang Marine Corps over in South Carolina.” Brother Hayden spent twenty-two and a half years in the Army.

“There’d have to be something drastic,” Boyd says, before he or Carl would sell any of their land. “It’ll be handed down to my children and grandchildren.” He and Helen have two sons and a daughter: Gerald is a machinist; brother, Mark, a civil engineer; and their sister, Sandra, a pharmacist.

PLATE 62 Barn on Foster farm

Adding to the attractiveness of the Foster land is the closeness of the Little South Fork of the Cumberland River. The 688-mile-long Cumberland River runs through Kentucky and Tennessee. The Fosters own property that abuts land the government bought before impounding the river to build picturesque Lake Cumberland for flood control and to generate hydroelectric power.

Land is important, Boyd Foster says, “but family is more important, more important than money.” He and his siblings were taught to always look out for one another, of course, but also to help their neighbors.

“Back years ago,” he says, “people would help each other. If you went to visit someone, whatever they were doing, putting up corn, gathering hay, cutting firewood, whatever, if you was big enough, you’d work with them just like you was at home. If they come to visit you, they done the same thing.”

That’s what a community, a true community, is all about. And their community, the Fosters believe, is the best. Just consider its name: Freedom.

Boyd thinks the community got the name because so many in that area fought for the freedom of America. “I’ve been told that,” he says, “and I couldn’t prove that one way or the other, but it makes sense to me.”

Many of the early settlers and members of the Kentucky Militia fought in the American Revolutionary War, and when the Civil War broke out, Kentucky, being a border state between the Northern and Southern forces, sided with the Union. Well, most Kentuckians did. The Confederacy also had its sympathizers in Kentucky, and some of them lived in Wayne County.

On August 30, 1861, a countywide meeting was held at the Wayne County Courthouse in Monticello, and a respected Baptist preacher, W. A. Cooper, spoke for two hours and twenty minutes before a resolution was offered to ease tensions between the two factions. The resolution, which passed almost unanimously, said, among other things, that “we the people of Wayne County should remain loyal citizens, and that we organize home guards as the law directs and that we arm and equip ourselves for self-defense alone.”

In other words, the people of Wayne County wanted to forget political divisions and live in peace. The county’s residents even voted to hoist a white flag with the inscription “Peace is the motto of Wayne County,” and to give other such proofs to “convince the world that we are for peace.”

Today, Monticello is often called “The Houseboat Capital of the World” because of the large number of houseboat manufacturers in the city. The health of the local economy depends greatly on recreational and tourist traffic to Lake Cumberland.

In the early part of the twentieth century, however, black gold became the moneymaker when huge pools of oil were discovered in the strata of Wayne County. Entrepreneurs seeking their fortune swelled the town’s population from 413 residents in 1890 to more than 1,300 by 1910. Coal was also mined in the area, but “most people didn’t object,” Boyd Foster says, “because a lot of them got a lot of money out of that.” The county lies in both the Mississippian plateau and the Eastern Kentucky coal fields.

People in Wayne County and Monticello are serious about preserving stories of their past, of which they have no shortage. David H. Smith, executive director and curator of the Wayne County Museum, shares a few.

Take, for example, the unusual way Monticello got its name.

“When they were trying to come up with a name of the town,” Smith says, going back to about 1801, when the town was created, “there was this prominent family whose last name was Jones. They wanted to name the town Jonesboro. The rest of the squires, or whatever they were called, didn’t want that name, and this sixteen-year-old boy offers the name Monticello as a compromise. And they jumped on it, more or less to outvote the Joneses.”

PLATE 63 David Smith knows the history of the area.

That boy’s name was Micah Taul, and he served as the county’s first court clerk, perhaps because he could read and write, which at the time was uncommon. Taul went on to become a lawyer, a leader in the War of 1812, and a congressman.

And then there are the stories of a Cherokee Indian the white people called Chief Doublehead. But the Cherokee disagreed about his name. They called him Chief Chuqualatague, a leader of the Cherokee people of the Cumberland River. The chief is said to have had a son, Tuckahoe, and a daughter named Cornblossom, whom the white fur traders called “Princess Cornblossom” because of her beauty.

The local story says that Cornblossom took part in the vengeance killing of a stranger. The stranger reportedly bribed a young Indian to swap a chunk of silver for a rifle, Smith says, and the Indian died in the process. Cornblossom and some of her young braves caught up with the culprit and shot him. This incident was described as “Vengeance at the Turtle Neck Ford,” according to local legend.

“People will come to the museum and say, if they’re from here, ‘We go back to Princess Cornblossom,’ who supposedly married a white fur trader,” Smith says. “Some people don’t even believe she ever existed. It’s possible that she did exist. It makes a pretty good story that way. Sometimes the story is better than the truth.”

Whether the chief was really from Wayne County is debatable, Smith says. He moved around quite a bit. But it is a fact that he made deals with the government concerning land cessions, and that may have led to his undoing. When land was given up for trade goods, it seems the chief got first pick. In 1808, he was either murdered or executed for treason after negotiating a land cession without the consent of the Cherokee National Council.

It is also a fact, Smith says, that Chief Doublehead, or Chuqualatague, took part in approving the Holston Treaty in 1791, and met with George Washington and his representatives in 1794. The treaty established terms of relations between the United States and the Cherokee, assuring the tribes that they would fall under protection of the government.

Wayne County even has its own Daniel Boone story. Boone apparently joined other long hunters—eighteenth-century explorers and hunters who conducted expeditions into the frontier wilderness for long periods of time—in the Meadow Creek area of the county in the 1770s.

But, contrary to popular belief, Smith says, there is no evidence Boone owned land in the county. However, another Daniel Boone, or Boon, was in the county by 1813 and did purchase Wayne County property, records at the courthouse show. That Daniel was the great-nephew of the famous one.

And then there’s a musical twist to Wayne County’s history. Richard “Dick” Burnett was born on October 8, 1883, in an area near Elk Springs, about seven miles north of Monticello. You may not have heard of Burnett, but if you saw the movie O Brother, Where Art Thou?, you heard his song “Man of Constant Sorrow.” Many in the music business credit Burnett with writing that song around 1913, about six years after he lost his eyesight when a robber shot him in the face. Blindness forced him to quit his job in the oil fields, but his boss encouraged him to make music his livelihood.

Burnett was proficient on the banjo, dulcimer, and fiddle, and had been since he was thirteen. In time, he met Leonard Rutherford, a fourteen-year-old orphan who, as Burnett’s student, became “one of the smoothest fiddle players around,” Smith says. “They would play their music anywhere they could, often setting up on courthouse lawns or on the street. Dick would strap a tin cup on his knee for donations. They became very popular locally, and future fiddle and banjo players would mimic their style of playing.”

Burnett was a prolific songwriter. He picked up on tunes such as “Pearl Bryan,” “A Short Life of Trouble,” “Weeping Willow Tree,” and “Little Streams of Whiskey,” all songs he helped preserve or may have written, according to Smith.

But did he really write “Man of Constant Sorrow”? If he did, he gave it a different title: “Farewell Song.” In 1928, Emry Arthur recorded the song under the better-known title. That title stuck and it was recorded in the 1950s by the Stanley Brothers and in the 1960s by Bob Dylan. Smith says that when Burnett was asked about the song late in life, he replied, “No, I think I got that ballad from somebody, I dunno, it may be my song.”

Burnett died at ninety-three on January 23, 1977, “without really realizing the influence he had on old-time Appalachian music,” Smith says.

Like most people in Wayne County, the Fosters enjoy the local history stories and legends. But they’re more intrigued by stories handed down by their parents and grandparents. Boyd Foster tells about his grandfather Allen Foster cutting trees in the autumn months and putting his brand on each log. Then, in the wintertime, when the water level was up, he’d remove the scotches, allowing the logs to roll downhill and into the river. Foster and other loggers would walk the river banks, using hooks to guide the logs to Burnside, where a huge boom picked them up and deposited them at a sawmill. Each man was paid according to how many logs he turned in.

Carl Foster treasures memories of his family. Pictures of family members line the walls of his home, reminders of how things used to be.

These are the stories that matter. And these are the memories of home, in a community called Freedom.