Music in Southern Appalachia

Bluegrass, country, and shape note singing

PLATE 79 Pickers and singers at Clay’s Corner on a typical Friday night

PICKERS OF MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS are everywhere in Southern Appalachia. They’re playing in senior centers, in auditoriums, in town squares, in state parks, in gas stations, at family reunions, at campsites, in living rooms—even in a McDonald’s restaurant—wherever people gather, all over the region. The hills and hollers are alive with the sound of music that some people may have thought dead.

“There’s a whole generation of people in their twenties and thirties for whom there’s a pique of interest in the old-time Southern string band music,” says David A. Brose, folklorist at John C. Campbell Folk School. “Young people are taking it up with a vengeance.” Other styles of old-time music, folk songs, ballads, early country, and even shape note singing, which dates back to the early nineteenth century, are thriving in the South.

You can’t really call it a revival of Southern string band music because it never left, Brose says. It’s just that young people are catching on to what their elders have known all along: that there’s beauty, emotion, and grace in the old-time music. And it’s downright fun to play. That’s why pickers in places like Brasstown, North Carolina, and Auraria, Georgia, don’t give up their jam sessions without a good reason.

Clay Logan, proprietor of Clay’s Corner in Brasstown, says he’s closed his store to musicians only about ten times in twenty-eight years. Admission is free, but Logan would appreciate your buying a pack of Nabs and a Coke, or something.

“Sometimes we’ll have just three, and other times we’ll have more pickers than we do listeners,” Logan says. You’d be surprised, he adds, how many people can crowd into a back room that measures twelve by thirty feet. “Some are sitting, others are standing, folks just eating ice cream and having a good time.”

(Logan, by the way, became regionally famous, or infamous, several years ago when he started competing with the Peach Drop in Atlanta and the Times Square Ball Drop in New York City to count down the last minute to the New Year. He decided to lower a live, caged possum, safely and slowly, outside his store in unincorporated Brasstown, as the year’s final seconds ticked away. However, in 2003, threatened by a lawsuit from PETA, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, Logan opted instead to use a dead possum, roadkill that had been washed and blow-dried, he says, tongue in cheek.)

In Auraria, the only thing that’ll keep the pickers away is voting day, says Ray “Cowboy” Harris, a former rodeo rider who’s keeper of the key to the community house, which is also used as a voting precinct. “On voting days, we go somewhere else,” he says. Even a small flood that sent water under the door in the spring of 2015 didn’t stop the show, which costs you a dollar admission to help pay the night’s rent of twenty-five dollars.

PLATE 80 Rebecca Carter watches her fellow musicians.

Auraria attracted a passel of prospectors in 1832, when gold was discovered, and then a hotel and a bank, everything now long gone. But on a sultry Monday evening, relative newcomers to the jam session are trying to discover, not gold, but the right chord. Rebecca Carter is there with her guitar, but she uses prompts on major and minor chords because she’s still learning. Doris Burzynski uses a tablature to find the right notes on her Q-chord.

Everybody who shows up with a stringed instrument is encouraged to join in, and sing, too, even if he or she is not ready for prime time. “Some are good, some are not so good,” Cowboy Harris says. But having fun is the goal, not proving perfection.

Madge Whelchel has been an Auraria regular for years and used to run the show. “I grew up with music,” she says after refusing to tell her age, although she admits she’s older than Judge Judy on TV. “All we had was a radio. People would come to our house to listen to the radio, to listen to the Grand Ole Opry. We’d have a house full, and I lived way out in the country.”

It was the advent of radio that changed music everywhere, including, eventually, the mountains of the Southern Appalachia.

“It opened up music,” says Wayde Powell, Jr., “but it diluted it at the same time, because it was more composite, and the various strains of mountain music began to disappear. There were certain people who tried to preserve them.” In the remote, isolated mountains, however, change came slowly, and the sound “maintained its novelty as Southern Appalachian music.”

PLATE 81 Waiting for their time to sing…Jamie Shook and Wayde Powell, Jr.

Powell grew up in those mountains, in Towns County, Georgia, and he’s been a follower, an aficionado, really, of old-time Southern music all his life. At one time, he published a magazine, Precious Memories, which covered it all: gospel music, bluegrass, old-time, and country gospel. He and longtime friend Jamie Shook play in a group called the Ellis Walden Band, and they’re joined occasionally by versatile Wayde III, whom Brian Littrell of the Backstreet Boys referred to as “one of the best and most professional musicians I have had the pleasure of working with,” sometimes performing in state parks.

In the early 1900s, mountain people told their story in song, Powell says. Singing was part of life; it wasn’t separated from everyday events. “If you were hoeing corn, you sang. The family got together at night, you sang. You sang about events that took place in your life.”

Young people, however, even those who grew up around old-time music, sometimes miss the stories altogether. Powell’s sons, Wayde III and Nicky, “were pretty good size before they realized what songs were saying,” their father says. “They sang songs, they played songs, but they didn’t listen to the words.”

But music, like food, depends on a person’s taste. Powell’s young daughter wants to listen to Taylor Swift, while Wayde III would stay up all night trying to master the banjo if he could. “It used to be I couldn’t sleep if I didn’t hear a banjo playing,” Powell says.

Today, the emphasis is more on the beat and the voice, which may have been doctored in a studio. “But can they go out onstage and duplicate what comes out of the studio?” Powell wonders. “Nowadays, people dismiss what they consider not quality voice. They’re used to having these professional voices and commercial songs. Like growing tomatoes, who wants to hear a song about that? But people used to sing about things like that.”

The roots of the old-time Appalachian music grow deep and far, and not just to Ireland, Scotland, and England. Almost as important, David Brose says, is the influence Africans and African Americans had on Appalachian mountain music. The fiddle is a Western European instrument, but the banjo came from Africa.

In Ireland, he says, a fiddle tune must be played a certain way. If a fiddler slips in a note that doesn’t belong, one that’s not right, he might be asked to leave the session. “But Africans, when they took up the fiddle, brought a whole syncopation to the music,” says Brose, who plays guitar, banjo, mandolin, and several West African instruments. “Fiddle music changed in the Appalachian Mountains because of blacks bringing syncopation into the fiddle music.”

Brose teaches the history of Southern Appalachian music and its instruments, but during Morning Song, when students at the folk school gather to greet the new day with music, they like to mix it up. He’s likely to open with something like “Waterbound and I Can’t Get Home,” an old folk song with repeated lyrics, and then follow with “King of the Road,” a Roger Miller favorite that dates back more than fifty years. “People love it,” he says, and they sing along. “Some songs are literally a hundred years old.”

Shape note singing goes back even further, more than two hundred years. And it’s still being taught, thanks to groups like the North Georgia School of Gospel Music. Lilly Vee Adams of Blairsville, Georgia, was partly responsible for the school’s development. She grew up with shape note music. “My daddy, the late Paul Gibson, taught singing school,” she says. “There were four of us girls; one of them was older, so she could sit where she wanted to.”

But the other three were told to sit on the front bench while Adams’s father taught shape note and lines and spaces, two ways to sight-read songs without learning by rote the scales of all twelve keys of music.

“We’d get a new singing convention book,” she says, “and Daddy would sit there and hum and sing those songs. I was raised on it. I’m still not absolutely perfect in it.”

The gospel music school meets annually for two weeks at various colleges in North Georgia. It’s open to everyone, but most of the students range in age from seven to eighteen, with a few older people there, some to chaperone the children.

“The reason it’s so easy to sing shape notes is because the shapes are right there in front of your eyes,” Adams says. Shapes were added to the note heads in written music to help singers find pitches within major and minor scales. “You don’t have to worry about a C or a D or anything like that. You know C is a do,” as in do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do. Here’s what Adams teaches her grandchildren, who have attended the school: Do is like a triangle; re is a half-moon; mi is a diamond; fa is a flag; so is like a zero; la is rectangular; ti is shaped like an ice-cream cone, then you’re back to the high do. The children love shape note singing, she says. “They think it’s something else.”

Not everybody, however, is only enamored with bluegrass, string bands, and old-time mountain music. One of them is Sharon Thomason of Dahlonega, Georgia, author of Sing Them Over to Me Again: Loving Memories of Classic Country Music, published in 2013. As the book title implies, Thomason loves the singing of such country singers as Eddy Arnold, Bill Anderson, Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, Ernest Tubb, Dolly Parton, and Loretta Lynn. She was turning the radio dial to find good country music when she was just a small child.

But, she says, “if you go back and try to listen to the Bristol Sessions of the 1920s, to Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family, it’s kind of hard to listen to, almost.” Ralph Peer, producer for the Victor Talking Machine Company, held the Bristol Sessions in 1927 in Bristol, Tennessee, and turned out recordings of blues, ragtime, gospel, ballads, topical songs, and string bands. The sessions marked the commercial debuts of Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family.

And she’s not crazy about many of the singers, country and otherwise, who are popular today. Listening to Willie’s Roadhouse on satellite radio one day, she heard two performers, Canadian singer and songwriter Michael Bublé and Eddy Arnold, sing the same old Arnold song back to back. “Michael sang, and I thought, ‘Oh, he did good.’ Then Eddy comes on and sings, and I think, ‘Oh my god, there’s no comparison.’ The emotion that Eddy Arnold could put in a song. These people today just don’t have any emotion. But twenty years from now, will we look back and still feel that way about it?”

That’s because tastes in music change a little with every generation, she says. And people of each generation think their music is the best, and that any music that comes later has lost some of the real stuff. When the Nashville Sound came along in the 1960s, singers like Jim Reeves, Patsy Cline, and Ray Price offered a smoother kind of country, and some folks complained it wasn’t country anymore. “Now we see that the Nashville Sound saved commercial country music,” Thomason says.

But old-time music did have a positive effect on the country stars of a couple of decades ago. Back when the Jordanaires were backup singers for Elvis Presley, Patsy Cline, and Eddy Arnold, Thomason says, the “cheat sheet they used when they were recording, they wrote that out in shape notes. They had all learned that in church.”

Regardless of the style a person enjoys, the fact is music is soothing to the soul. Psychologists recommend that their anxious patients listen to good music, the kind that represents how they want to feel, and hospice staff and volunteers know that songs often are the last thing a person dying with dementia will forget. Hugh P. Minor III of Danielsville, Georgia, a spiritual care coordinator with Gentiva Hospice in North Georgia, tells this story about a patient:

Minor was called out to an assisted-living facility to help a family through their grief. A loved one was dying (hospice calls it transitioning). He sat and talked to the patient’s family members for a while, and then, “I don’t know what it was, but something struck me and I offered to the family to sing,” he recalls. “I knew the words of ‘Blessed Assurance,’ so I asked the family if it was okay to sing. They said sure. So, we were holding hands. We prayed and then I sang the first verse.

“The patient hadn’t said a word, hadn’t said anything for many, many hours to her family. When she heard that song, she opened her eyes and sang parts of the chorus. When we finished, she looked over at her family and closed her eyes. She died several hours later.”

The part of the brain where music resides is the last part to deteriorate with dementia diseases, Minor says. The patient may not have known him, and she may not even have remembered the song after he walked away thirty seconds later. But she knows she had a nice, warm feeling hearing the music and maybe singing the song. “That’s why,” he says, “I sing the praises of the group of people who come together to do this thing called hospice.”

Music can be used in teaching many things. Writing good storytelling ballads, for example, Kate Long will tell you, is like writing a good newspaper story. It’s all about communication. Long should know. For thirty-two years, she was writing coach for The Charleston Gazette in Charleston, West Virginia. She has led seminars and conferences on newspaper writing and songwriting all over the country, and she’s also a storyteller, singer, and songwriter whose songs have been recorded by dozens of artists.

“The same kinds of principles that apply to newspaper writing also apply to lyrics of song, poetry, and what have you,” she says. You’re trying to communicate with people by using straightforward sentence construction, plain English, vivid details, movement through time and space, inventorying a cast of characters to convey an idea, all those things Long taught in her writing sessions.

She quotes William Zinsser, author of the classic On Writing Well, in making her point: “Clutter is the disease of American writing.”

“One of the reasons I love Southern string band music,” she says, “is that the best Southern songs are excellent examples of straightforward, lyrical storytelling. They usually involve a tightly spun plot and memorable detail, all put together in a short, compact package.

“And more and more young people are attracted to this kind of music,” Long says, agreeing with Brose. “They show up in droves, musical instruments in hand, at the Vandalia Gathering in Charleston. They’re everywhere at West Virginia State Folk Festival in Glenville, West Virginia. At the Appalachian String Band Festival in Clifftop, West Virginia, about forty percent of the participants are under thirty years old. What young people may not learn in school, they might well learn in writing and performing good storytelling songs, and that is: If you wouldn’t say it that way, you shouldn’t write it that way. Just use simple, comfortable words that people can identify with.”

Long mentions Jean Ritchie and Hazel Dickens, two songwriters and icons in Southern music, as role models. But Long herself, a singer with a dusky, alto voice, has written ballads that have won national awards. Here are the lyrics of one that strikes home with people of Southern Appalachia:

Who’ll Watch the Home Place?

Leaves are falling and turning showers of gold

As the postman climbs up our long hill.

And there’s sympathy written all over his face

As he hands me a couple more bills.

Who’ll watch the home place?

Who’ll tend my heart’s dear space?

Who’ll fill my empty place

When I am gone from here?

There’s a lovely green nook by a clear running stream.

It was my place when I was quite small,

And its creatures and sounds could soothe my worst pains

But today they don’t ease me at all.

In my grandfather’s shed there are hundreds of tools.

I know them by feel and by name.

Like parts of my body, they’ve patched this old place.

When I move them, they won’t be the same.

Now I wander around touching each blessed thing,

The chimney, the table, the trees

And memories swirl ’round me like birds on the wing

When I leave here, oh, who will I be?

Most of what they’re singing in Auraria or in Brasstown and elsewhere are not necessarily songs of Southern Appalachia. They’re just songs people want to play and hear. Besides, old folk songs and ballads of the Appalachian Mountains and Western Europe often get reworked and reworded, copyrighted and commercialized into a hit, and it’s hard to tell sometimes which songs are true Southern Appalachian and which ones are pretenders.

Says David Brose: “Bob Dylan stole many, many classic ballads very early in his career, changed them only slightly and slapped a copyright on it, claiming authorship. Nobody called neither Bob nor Paul Simon out for doing this, because ninety-nine percent of Simon and Garfunkel and Dylan fans were not themselves ballad scholars. Just a few of us knew where Paul Simon got ‘Scarborough Fair.’ ” He obviously got it from “The Elfin Knight,” one of the oldest ballads in the English language.

The same thing is true of “Tom Dooley,” made famous by the Kingston Trio. It was first collected from a North Carolina tobacco farmer named Frank Profitt, Brose says, and later by folklorist Frank Warner. Alan Lomax put Warner’s version in a book, and the Kingston Trio found it there. “The Kingston Trio made it sound ‘modern’ and made a multimillion-selling hit out of it,” Brose says.

And if you’ve seen the movie O Brother, Where Art Thou?, you no doubt remember the hymn with these words: “When I went down to the river to pray,” which was adapted from a traditional hymn with the lyrics: “When I went down to the valley to pray.” It was changed to fit with the baptism scene in the movie.

“Now I hear it many places,” Brose says. “At weddings, funerals, church services, and it has entered popular use with the word ‘valley’ being replaced by ‘river.’ Pop culture strikes again.”

Meanwhile, back in Auraria, Georgia, Cowboy Harris kicks off the singing with “Crystal Chandeliers,” a song made famous by country singer Charley Pride decades ago.

Mark Kersh follows up with “Blessed Jesus, Hold My Hand,” and then singing flows clockwise around the room, starting with Kenny B. Bowers with “I Can’t Stop Loving You.” As couples begin to pair up and dance in the adjoining kitchen, Doug Cook yells out, “Give me a D as in dog,” and then sings “When You and I Were Young, Maggie,” a song whose origin is in dispute. Springtown, Tennessee, claims that a local, George Johnson, wrote the lyrics for his Maggie in 1864, and the town even erected a small monument in Johnson’s memory. Others say the lyrics were part of a poem by George Washington Johnson, a teacher from Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, who lost his Maggie at a young age. Whatever the case, some Maggie was immortalized in Auraria, Georgia, on this Monday night.

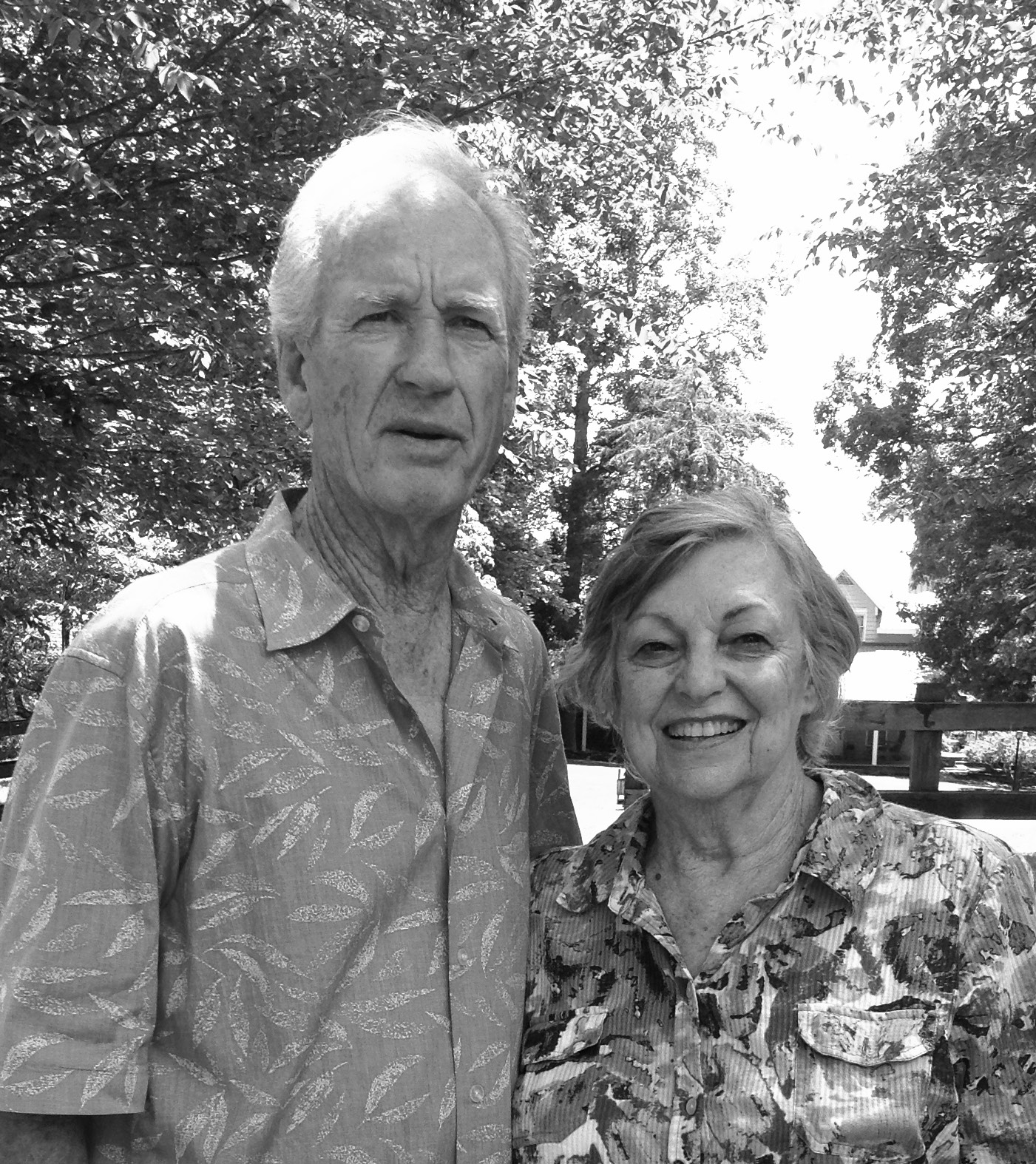

PLATE 82 Fred and Drucilla Stowers

Fred Stowers of Dawson County, Georgia, a lawyer turned businessman, steps up to the microphone and announces that he wants to experiment with a song. “Dad told me that life is a gamble,” he says, so why not enjoy yourself and try new things while you can? “If you’re alive, you’re still in the game.”

Stowers is proficient on the mandolin; he’s a good strummer, not a picker, on the guitar and banjo and even plays fiddle sometimes. He keeps a couple of changes of clothes in the trunk of his car, along with his golf clubs, so he can be ready for whatever occasion.

A few weeks later, Stowers and the Porch Pickers band are performing under a giant white oak tree at the Stowers family reunion, held on his hundred-acre farm, of which the main dwelling house was built in the 1830s. He performs somewhere every week, sometimes three times a week. He’s a regular at an assisted-living home nearby.

Some of the same pickers who show up in Auraria on Monday nights are performing at the reunion. There’s Dave McLaughlin on the banjo, who sings “Heartaches by the Number,” a hit by Ray Price fifty years ago. “He’s got a good, strong voice,” Rebecca Carter comments. “His voice has that country edge.”

PLATE 83 Madge claps at Stowers reunion.

There’s Maxx Bevins with his fiddle, a man who once lived in Baltimore, Maryland, and operated nightclubs on the Chesapeake Bay. “He had big-time bands coming through,” Stowers says, “and chaired the Appalachian Jam on the square in Dahlonega for a while.” (Bevins was seriously ill at the time of the reunion and died about a year later.)

Madge Whelchel is there at the reunion, clapping in time with the music and perhaps wishing she were up there on that stage, too.

In Auraria, Whelchel sings and plays “Goin’ Down the Road Feelin’ Bad,” a song first recorded in 1924 and made famous by Woodie Guthrie. But then she gets to “feelin’ bad about singin’ it,” she says, and quits before the song ends.

But nobody feels bad at the end of the jam session. That’s what music does to people. It makes them feel a little better about life and where it’s taking them. Sometimes it makes them smile. Sometimes it’s a catharsis, something to purge the tensions of everyday living. Most times, it’s nice to just sit back and listen.

Every person has his or her preferences. But, thank goodness and thank musicians, good music—old-time and more modern—is still wafting through the hills and valleys of Southern Appalachia. May it always be so.

A SHORT PRIMER ON MUSICAL TERMS

Folk song: A folk song has no known author. It has been handed down from generation to generation. A folk song does not tell a story; it has no narrative quality. An example is “Old Joe Clark,” every verse of which may be coherent unto itself, but taken together, the verses do not tell a cohesive story.

Ballad: A ballad does tell a story; it is a narrative folk song. Sometimes, songwriters will use the term “lyric song” to mean a folk song that does not tell a story, and the term “ballad” to refer to a traditional song that does. “The House Carpenter” is a ballad. “Barbara Allen” no doubt is the best-known ballad in America. Sometimes, the lines between folk song and ballad can get blurry.

Shape note: Shape note music is a system of efficiently learning the basics of music theory. With an understanding of shape notes, one can sight-read songs without needing to depend upon learning by rote, or by “ear.” Young people throughout the Southeast today are being trained in shape note music (particularly the seven-note system) so that they can lead music in their local churches with conviction and confidence. The shapes (do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do) correspond to the relativity of pitches found within any musical key. The beauty and power of the shape note system is that once a singer understands and can hear the relativity of the pitches within the musical scale, he can then transpose that relativity to any chosen key of music, thus eliminating the need to learn the scales of all twelve keys. Learn one scale and transpose it eleven times. Because of shape notes, when the newly published annual songbooks are brought out at today’s local, state, and national singing conventions, all singers can sight-read (i.e., sing without previous rehearsal) every song in the book, because they understand the relativity of the pitches displayed by the various shapes on each page of music. They quickly master the tune of each song and can focus more intently on the words they sing.