Grounded in Folk Tradition

The story of Hedy West

HEDY WEST had a knack for getting her way, even as a child. If she didn’t want to help her older sister wash dishes, suddenly it was time for piano practice. And no one could disturb Hedy when she was at the piano.

Hedy was brilliant—she began first grade at four years old and graduated high school at fifteen—and she had little patience for stupid people doing and saying stupid things. Nothing changed when she became an adult.

She was a magnificent musician, songwriter, and folk singer who made a name for herself wherever she went, even in England and Germany. She was performing in the Jacksonville (Florida) Symphony Orchestra when she was thirteen and could play practically any musical instrument she picked up. She wrote many folk songs, the most famous being “500 Miles,” made popular by Peter, Paul and Mary. The great English folk musician A. L. Lloyd reportedly called Hedy “far and away the best of American girl singers in the [folk] revival,” the era of Joan Baez, Jean Ritchie, and Judy Collins. Today, more than ten years after her death, Hedy’s original compositions, along with traditional songs she collected in Appalachia, are still popular with folk music fans.

Hedy grew up in a working-class family in the mountains of North Georgia and received the bulk of her repertoire directly from her family’s musical heritage. Because of that, music historians have said, she was more grounded in the folk tradition than other prominent folk musicians, such as Baez and Collins. Her father, Don West, introduced her to songs of Southern textile mill workers and miners, and Hedy herself described her work as chronicling the “lower classes” with songs like “Cotton Mill Girls,” “Whore’s Lament,” and “Come All Ye Lewiston Factory Girls.” Her music often reflected social and political problems of the twentieth century. Her songs gave voice to children and parents forced to work twelve-hour days in textile mills to support their families.

Hedy despised President Lyndon Johnson’s administration and delighted in singing songs opposing the Vietnam War. She sometimes turned familiar melodies into cutting lyrics of her own. “Jingle Bells,” for example, became “Riding Through the Reich,” a sarcastic Nazi commentary, and “Go Tell Aunt Rhody” morphed into “The Poverty War Is Dead,” a humorous slap at Johnson’s attempt to eradicate poverty in America.

Hedwig Grace West was born in Cartersville, Georgia, on April 6, 1938. At the time, her family was living on a farm just outside of Cassville, at one time a sizable Appalachian town that was brought to its knees during the Civil War when General William Tecumseh Sherman and his troops came through on their way to Atlanta, burning practically everything.

Don West had built a house with knotty pine walls for his family, while his mother, Hedy’s grandmother, Lillie Mulkey West—“Bamma,” one of the grandchildren started calling her—lived in the old homeplace on the property. Don was a well-known Southern poet, an educator, an ordained minister, a labor organizer, and a leftist activist who moved from one activist project to another and from one teaching job to another. His wife, Mable Constance “Connie” West, was also a teacher.

Hedy’s sister, Ann West Williams, five years older than Hedy, had already started school before her family moved to Cassville from Bethel, Ohio, where Don West had been preaching. The Wests knew many homes over the years. They lived in several places in Georgia: in Lula in Hall County, where Don West was superintendent of Lula High School and where his wife taught; just outside of Atlanta, while he taught at Oglethorpe University; in Meansville, where he was minister of a church; in Ringgold, where Connie West taught school while her husband was in New York working on his doctorate at Columbia University; and on a farm on the Chattahoochee River near Douglasville. For a while, Connie and the girls lived in Fernandina Beach, Florida, where their mother taught school while her husband stayed on the farm to grow and sell vegetables. At one point, Don West landed a job in Texas, but he didn’t like it there, so he left.

If Hedy were alive today, no doubt she would say it was her grandmother, Bamma, who lit the musical fire in her. Bamma [herself profiled in the story beginning on page 235] was a folk singer, songwriter, and storyteller who ran a country store near Blairsville, Georgia. She sang a folk song similar to “500 Miles,” could play the banjo, guitar, and Dobro, and like Hedy, she had a quick wit and a sharp tongue. One day, a city slicker walked into Bamma’s store and said, “Ma’am, can you tell me where this road’s going?” She replied, “Sir, this road’s been sitting here for thirty years that I’ve been living here, and as far as I know, it’s not going anywhere.”

Hedy also learned songs from her great-uncle Gus Mulkey. In an interview years ago, Hedy said her grandmother “specialized in sober or tragic songs, perhaps conditioned by her hard life, but Gus preferred humorous songs; indeed, he was not likely to sing unless he could extract a bit of fun out of the song.” Hedy combined both humor and sadness for her own songs.

Recalling their childhood, Ann Williams remembers, “In the evenings, after supper, we would sit on the floor in front of the fireplace in the bedroom, and Bamma would tell us stories, play her guitar, and we would sing the old songs she knew.” Her grandmother also had a Victrola record player on tall legs. She would wind up the arm on the side of the machine and play some of her favorite songs for her grandchildren.

Hedy was a quick learner on practically any musical instrument. She could play flute, piccolo, banjo, guitar, fiddle, and, of course, piano. When she and her sister were living in Florida, she took up the accordion. She would play at women’s club meetings, and her sister would do a monologue.

Williams, a retired teacher and mother of five, admits she didn’t enjoy piano as much as Hedy. She would rather sing, dance, draw, and act. “I loved being onstage,” she says, “and would have welcomed lessons in anything other than piano.” She excelled in public speaking and won a national oratorical contest with a speech about the Statue of Liberty.

“Hedy’s inspiration to do anything was to beat [me],” she says, recalling growing up with Hedy. “She was very competitive, and I was not….I sang, but I didn’t like playing the guitar because it hurt my fingers. She wanted to do better than me. She was four years old when she started piano lessons, and by the time she was five, she was better. She took to music at the first opportunity.”

The girls lived in what Williams called a “split” family. Ann and her mother were close, while Hedy was Daddy’s girl. “Hedy could get anything she wanted from Daddy,” Williams says, but she was sometimes confrontational with her mother. “Daddy would get both of us girls in bed and read books to us. Big books. I remember him reading Cry, the Beloved Country, a novel about South Africa. “She would snuggle up to Daddy. She wanted to show that she was the favorite. She really was.”

“Hedy had a twangy, nasal sound to her voice,” Williams says. “She did that on purpose, imitating people in the mountains who sang that way.” And she refused to change her style to become more commercial.

But her twangy, lonesome sound didn’t hurt her popularity at all. She won a prize for ballad singing when she was only twelve, and as a teenager, sang at folk festivals near her home and in neighboring states.

After graduating from Murphy High School in Murphy, North Carolina, Hedy left home for Western Carolina College—now Western Carolina University—in Cullowee, North Carolina. She was an A student—school was always easy for her—but she was not impressed with her fellow students, or, for that matter, her professors, some of whom she challenged openly in class.

“She was already sort of raising hell as a college student because she disapproved of some of the activities of some of the fraternities and sororities on campus,” says Hedy’s daughter, Talitha “Tai” West-Katz. “She protested against the panty raids that were going on. That may have won her a few friends, but probably more detractors….She didn’t feel challenged at college.

“I don’t know if I would say my mom was confrontational, but she was principled. If something struck her as not being right, she never hesitated to speak out about it, and sometimes pretty bluntly.”

After getting her college diploma, Hedy headed immediately to New York City, where she studied music at Mannes College and drama at Columbia University. And she sang whenever and wherever she could. She was a fixture of the Greenwich Village folk scene, where people were singing the kinds of songs she grew up with. Pete Seeger, who became a good friend, invited her to sing with him at a Carnegie Hall concert. Soon she was making albums; the first one of which, New Folks, was released on the Vanguard label.

Ann Williams says Hedy went to New York and then overseas “to get away from her daddy. He wanted to tell her how to play, what to play, where to play, what to wear. He was very controlling—and to everybody. And Hedy was not going to be controlled.” Hedy also wanted to see the world beyond America, Tai says.

In the early 1960s, Hedy married a man in New York City. The couple later divorced, but remained good friends and kept in touch. Spreading her musical wings, Hedy moved to Los Angeles, where she established a new home base and continued to sing at events across the country. But she was also taking frequent trips to England. Before long, she moved to London full-time and lived there for seven years. She sang at folk clubs and appeared at the Cambridge Folk Festival and the Keele Folk Festival. She recorded three albums for Topic Records—Old Times and Hard Times, Pretty Saro, and Ballads—and one album for Fontana Records called Serves ’em Fine. In the early 1970s, she made her home in Germany, where she turned out more albums, including Getting Folk Out of the Country and Love, Hell and Biscuits.

“She told me she wanted to go to Germany [because] after the Second World War everyone had told her that Germans were the worst thing ever, and she wanted to find out for herself,” her daughter says. “I don’t know what she concluded about that, but I know she learned German, and she ended up singing a lot of songs in German and translating English songs into German.”

German audiences loved hearing American folk songs in their native language while American fans wanted the traditional folk music they were used to. But Hedy West was her own person, and she didn’t always abide by what others wanted.

Actually, she was a musical paradox. She had a voice from the hill country of Georgia, and yet she sang fluently in German. She wrote folksy ballads about love, marriage, and loneliness, yet she was trained as a classical pianist and was a devotee of Karlheinz Stockhausen, a controversial German composer. She received high praise from her fans everywhere, and yet she couldn’t always get along with her own family. “I loved my sister,” Ann Williams says, “but I will never understand her.”

Sometimes Hedy made choices simply out of convenience, as with her second marriage, to a man she met overseas. He was gay and worked for the BBC. She married him, her daughter says, so that she could work legally in the United Kingdom. That marriage also ended in divorce.

One of Hedy West’s best friends, Judith N. Drabkin of High Falls, New York, first saw Hedy perform at a concert in Manhattan and “was simply captured by her playing,” she says. Later, she telephoned Hedy and asked if she would be willing to give her banjo lessons. “And she agreed, which was extremely generous of her, to say the least.”

So for the next few months, Drabkin drove three and a half hours from Westchester, New York, to Stony Brook on Long Island, where Hedy lived, to receive lessons from the master banjoist. “She was one of the finest teachers I’ve ever encountered,” she says. “What she was endeavoring to teach me on banjo, she would somehow convert to theory taught from the piano. And it was the most brilliant teaching.”

The two enjoyed each other’s company, and the teacher-student relationship developed into a friendship that lasted more than forty years. Besides the banjo, Drabkin learned about gardening from Hedy, something the city girl knew nothing about. “In my opinion,” Drabkin says, “there was a force within her even more powerful and fundamental than her music. Deepest down at her roots, she was a farmer. That’s how I think of her.” Unfortunately, the township of Stony Brook was not as impressed and forced Hedy to remove a thriving, chest-high hedge of Rosa rugosa from all around the margin of her property.

It was on Long Island, at a faculty reception at Stony Brook University, that Hedy West found love that endured. His name was Joseph Katz, a professor at the university and a native of Germany. At the time, Hedy was a graduate student studying composition and teaching folk music. The first time Katz telephoned his future wife, she said, “Oh, you’re the man who can’t pronounce his ‘r’s.”

Drabkin knew Hedy as well as anybody, but she finds it hard to describe her friend’s personality, even though her outward appearance was powerfully impressive. “She would come into a room, and she might be inconspicuous at first, but inconspicuous rarely. She didn’t come in with a flourish. It was her very entry, her very movement. She did not have a dancer’s grace….She didn’t have a beautiful walk, but there was something about her presence that was attracting, very attracting.”

Hedy was a person of enormous complexity and dimension, Drabkin says. She loved her new man, Joseph, but she had a difficult relationship with his family. Still, she cultivated that relationship, dutifully attending the family’s Passover seders and other Jewish rituals. She did it, Drabkin believes, for her daughter. She wanted her to have a better sense of family than Hedy had herself.

Hedy had a profound sense of humor. At a performance in a little concert hall for Drabkin’s music club, she came out with a little sheath of notes—obviously her playlist. Each time she performed a piece, she would rip a note off the deck, crumple it up, and throw it on the floor. She told her listeners, “You should see my living room.” The audience burst into laughter.

She also was a visual artist. “If I weren’t a musician,” she told Drabkin, “I would have been an artist.” She gave Drabkin her very first oil painting, which, interestingly enough, was of her mother, Connie, with whom she was never close, Hedy’s sister says. That painting is now part of the Hedy and Don West collection at the University of Georgia.

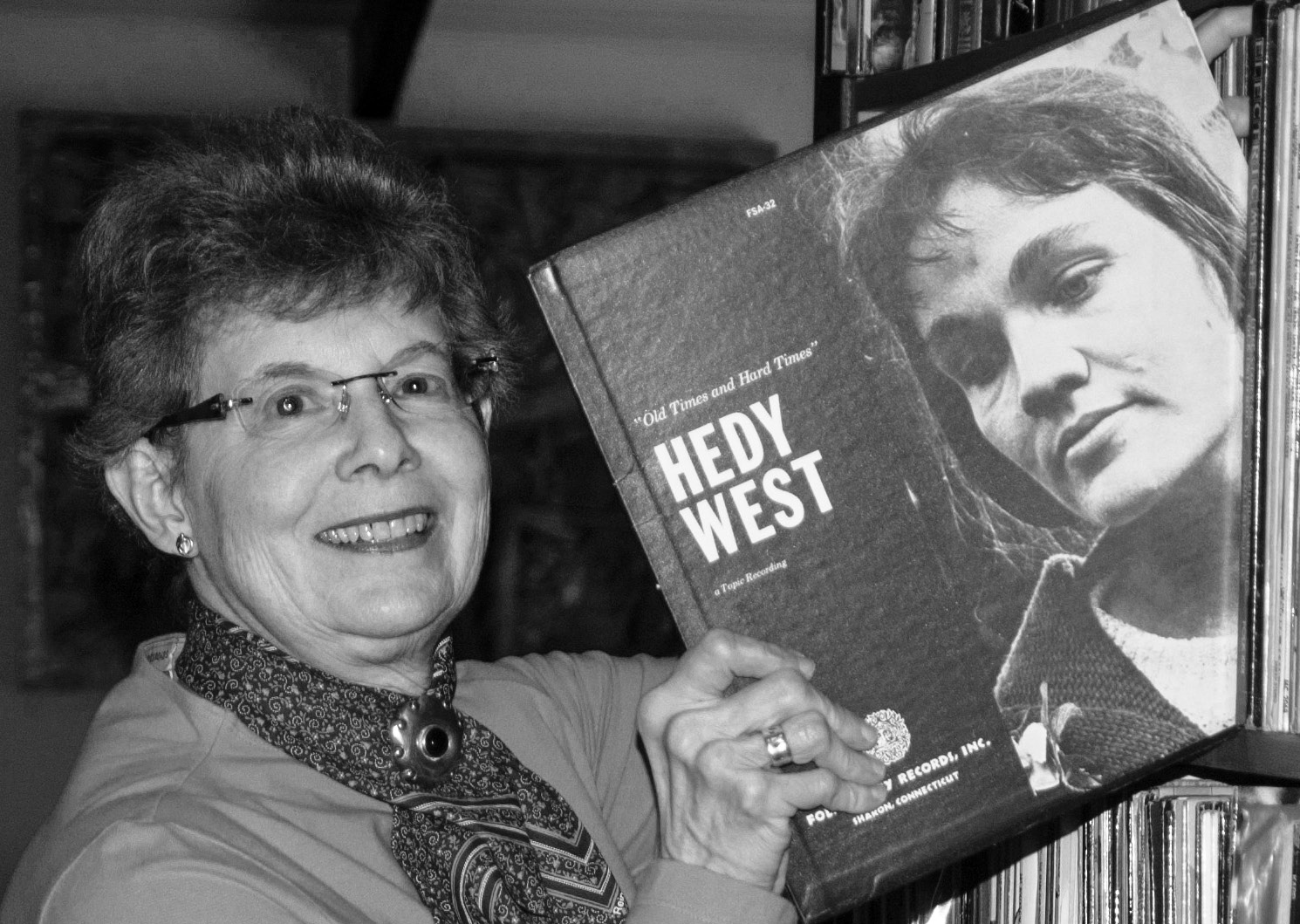

PLATE 84 Judith Drabkin holds one of Hedy’s albums. Mrs. Drabkin died February 7, 2017.

Hedy could be generous. During the late 1970s, while living in Stony Brook, she donated her talents to many benefit concerts for causes that met her approval. She was all of these wonderful things, but she was still an enigma. In a poem, her father described Hedy as a “strong and tender-hearted [person] whose troubled thoughts coursed deeply beneath a smooth surface.”

Hedy encouraged her daughter to learn to play the violin, and she did. Tai performed at her own bat mitzvah when she was thirteen. But near the end of her life, Hedy herself lost interest in performing, Tai says. She was more interested in the history of music.

By that point, she had turned out many great songs, and, much to the delight of her fans, some of her albums have been rereleased on CD. (In 2017, Tai says, a British record company, Fledg’ling, announced plans to produce an album of previously unreleased works, From Granmaw and Me, featuring several songs Hedy learned from her grandmother Lillie West.) Hedy also set some of her father’s poems to music, “Anger in the Land” among them.

Hedy was an innovator on the five-string banjo, a perfect instrument for her long arms. She developed her own style of playing, combining the clawhammer technique with three-finger picking. She also had her own style of singing. In fact, she sang a third above the tonal pitch, something she discovered with the help of a prominent researcher of ethnic music, Drabkin says. “So if you were playing in the key of C,” she explains, Hedy “wasn’t singing exactly in the key of C….She was singing a third sharp of that tone.” Nonetheless, Hedy’s singing melded beautifully with the music she played.

“I think she deserves a place of recognition,” Drabkin says, “not only because she was a girl who played a banjo, certainly a curiosity in those years, but because she was unafraid to bring the discipline, the excellence, the work, the perfection, to what many would think is—and has been—an informal music. And it takes a special brilliance to achieve that.”

Hedy became more introspective in her last years, her daughter says. “She believed that the most important thing in life was to develop understanding of the way the world worked, and ethics. She began to believe that having a sense of ethics and a moral compass was the most important thing in life.”

Hedy West died of breast cancer on July 3, 2005. She wanted no funeral.

“Lord, I can’t go back home this a-way,” goes a line from perhaps her most famous song, “500 Miles.” Maybe not. But a lot of people believe that Hedy West’s music, born in the mountains of North Georgia, has never left.