Lillie Mulkey West

Inspiring a new generation of folk singers

I interviewed Lillie Mulkey West, grandmother of folk singer Hedy West, in June 1972. The resulting story, most of which follows, was part of a series of pieces on Appalachian folklore published in The Times of Gainesville, Georgia. Lillie West died in 1982, but her songs, her stories, and her impact on the West family are still felt in the hills.

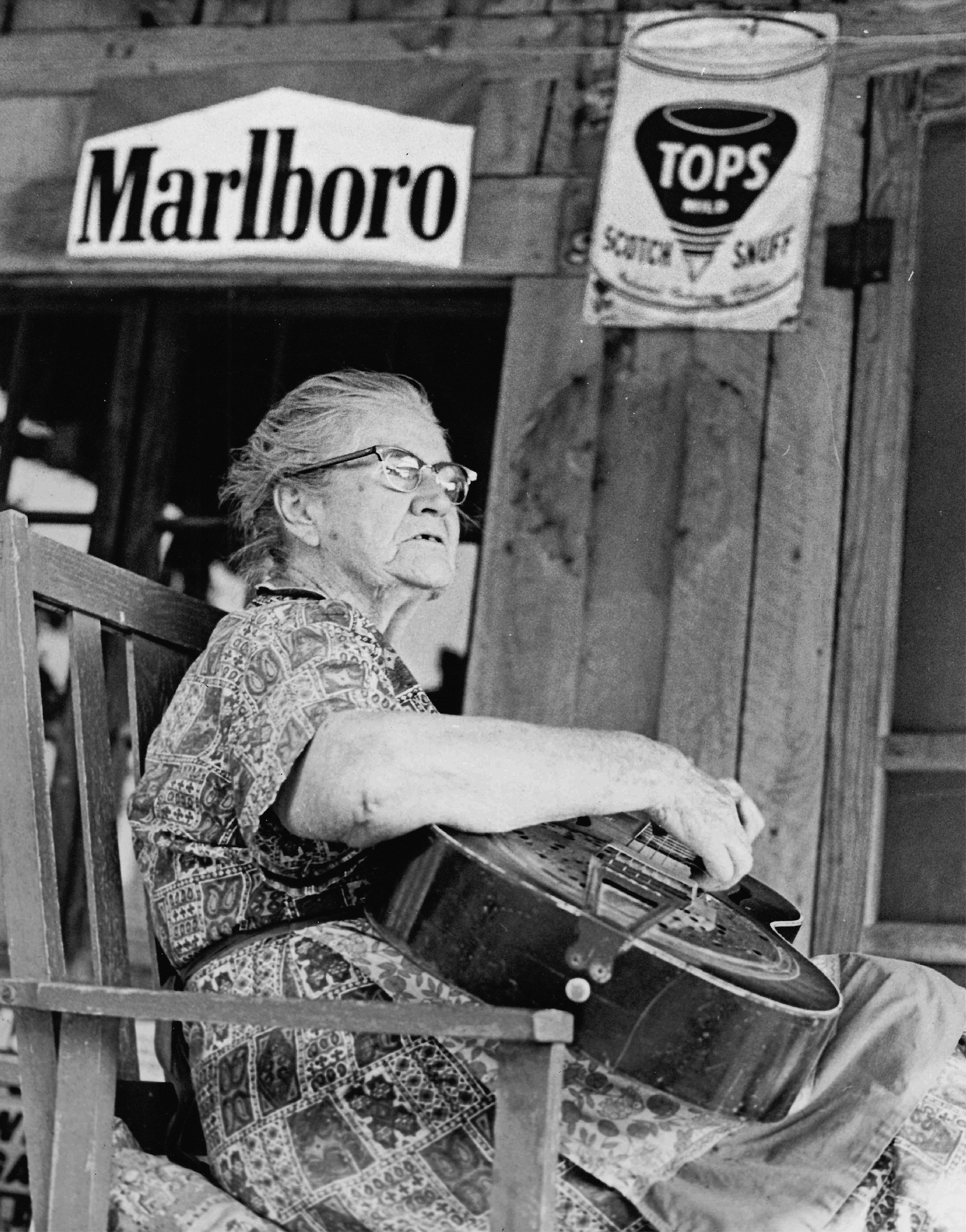

MRS. LILLIE MULKEY WEST leans back in her chair, smiles when she recalls the song she wants, strums a guitar that has one string missing, and begins to sing. Her voice, though cracked occasionally with age, is brimming with love for music that dates back about eighty years.

The song she’s chosen is about a man named Johnny Sands who married Betty Hague, who turned out to be a plague. Finally, Betty told Johnny that she was tired of life and tired of him. So Johnny said he’d drown himself in a river that ran below, and she said she’d wished that long ago.

Johnny asked Betty to tie his hands for fear he would try to save himself. She did. The couple walked to the hill; Johnny asked Betty to push him into the river, and just as Betty reached for his back, Johnny stepped aside and his wife fell in. Mrs. West sang the last stanza:

She’s splashing, dashing like a fish,

And cried, “Save me, Johnny Sands.”

“I can’t, my dear, though much I fear,

“For you have tied my hands.”

Mrs. West laughs with me, pleased that I have enjoyed the ballad. She gives another sample of her folk singing. Unafraid of political correctness, she sings several verses about how a woman’s tongue will run forevermore and ends the song this way:

There’s a lot of fun in sporting,

There’s a lot of fun in courting,

Pa says do begin it when you’re young.

If you want to marry a wife,

And be happy all your life,

Marry one that’s blind, deaf, and dumb.

A car pulls up outside Mrs. West’s small country store near Lake Nottely in Union County, Georgia. Sitting on the front porch, she finishes her song, not even noticing the waiting customer, who apparently doesn’t want to get out and interrupt her singing.

Finally told that it looks like someone wants to buy something, Mrs. West retorts: “Well, I reckon they can get out and come in if they want something. I don’t have a habit of running out to cars.”

The customer leaves, and Mrs. West settles back down to more songs and stories. In singing serious ballads, her whole personality seems to change. More of a country twang comes into her voice, and she holds her notes and stretches out her words. She sounds like a female version of recording star Bill Monroe. She’ll start singing a line with low volume, hit a peak in the middle, and then let the last word fade off at the end.

Singing has been part of Mrs. West’s life ever since she was old enough to learn a few words of song. Eighty-four this month, she was born and reared in Gilmer County, Georgia, and has lived in Union County since 1946. When I ask if she’s learned any mountain songs, she says she is about the only one who knows any.

“People don’t sing around here. They do at church, but the songs they have in church now are not like those I was used to singing in my younger days. I think this singing today is more jazz than anything else. Anybody that can dance can dance to the songs they sing in church.”

PLATE 85 Mrs. West picks and sings in a 1972 photo.

Mrs. West’s love for singing has touched many in her family, particularly one granddaughter, Hedy West, daughter of her oldest son, Don. Hedy learned many songs from her grandmother. She later wrote and recorded songs of her own and set several of her father’s poems to music as well.

Mrs. West is one of ten children in a family of Scotch-Irish descent. Growing up, the family would gather around the fire most every night and sing a few songs. There were always visitors on Sundays, and there’d be more singing.

Mrs. West rocks back under the snuff signs that decorate the old store front and sings another song her daddy used to like. And if a customer drives up, he won’t mind waiting till she’s finished.