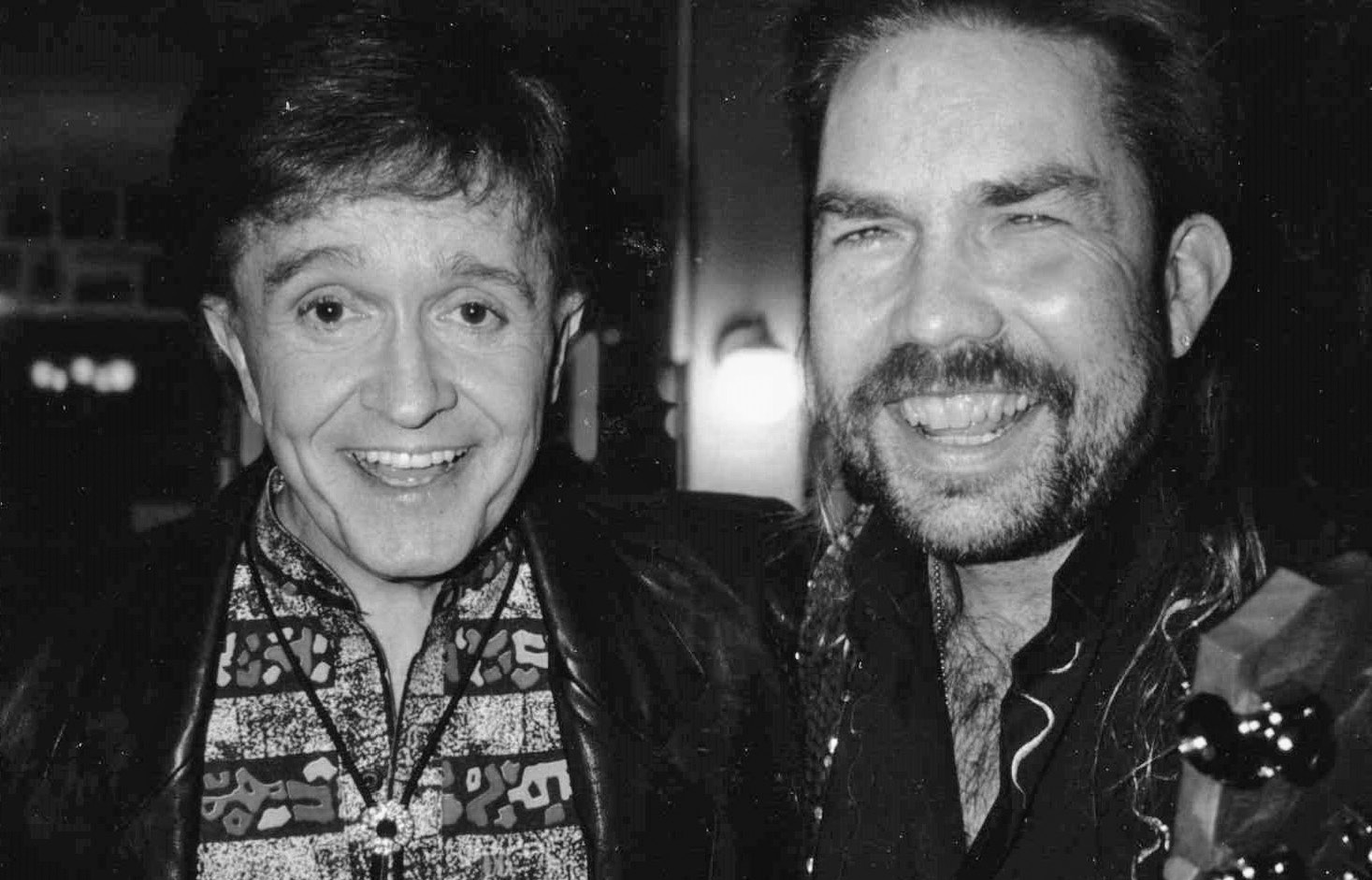

John Jarrard and Bruce Burch

Writers of country music

SOMETIME BETWEEN FINISHING high school in Gainesville, Georgia, and graduating from the University of Georgia in 1975, John Charles Jarrard and Walter Bruce Burch learned a little something about each other. They learned they each liked—and sometimes wrote—country music.

It happened this way: Burch was working as the night auditor at the Days Inn in Gainesville when Jarrard dropped in for a visit. A guitar was propped up in the office.

“I’ve got one of them, too,” Jarrard said. It wasn’t long until they were singing together in a bathroom of the motel. “We’d heard that the acoustics in a bathroom most closely approximated a recording studio,” Jarrard said in an interview in 1988. So one morning when Bruce got off work about seven o’clock, they went down to the bathroom of the manager’s suite.

The recording was horrible, Jarrard said. A little flushing in the background might have improved the sound. But they weren’t discouraged for long.

In March 1977, Burch decided to try his luck in Nashville. Jarrard helped him move.

“I took John to the bus station to go back to Gainesville and then cried like a baby,” Burch said. He was in Music City all by himself. About nine months later, Jarrard moved to Nashville as well. They were together again.

Writing songs was going to be easy, Burch thought. After all, he had found a company that liked some of his songs and had published them. Trouble was, published was as far as he got.

“I went to some hole-in-the-wall publishing company,” he said, “and they’d say, ‘Yeah, that one’s pretty good.’ I’d call John and tell him, ‘Hey, I got another one published today.’ I thought that was the greatest thing, to get one published. Of course, they didn’t give you any money for it.”

At this point, income had become more important for both men than it had been when they were younger: They had married women who weren’t willing to wait for number one songs before they ate again. The two men didn’t write much together because now they had reasons to stay home. Besides, both were lyricists, and lyricists normally cowrite with people who are more melodic. And then children came along, Matthew and Sarah for Bruce and wife Cindy, and Amanda for John and wife Beth. “We were busy with all that,” Burch said. “We were going our separate ways. But we talked every week or so. We kept the friendship up.”

Burch knew things were looking up one night in the late 1980s when he stopped at a Waffle House on his way back to Nashville from a friend’s wedding in Knoxville. As usual, he checked out the songs on the jukebox. And he smiled.

“I called John the next morning and said, ‘Man, we have finally made it big. We are both on the Waffle House jukebox.’ ” There they were, two country songs written by two city boys from Gainesville, Georgia, guys who had been together nearly as long as Homer was with Jethro. And both on the jukebox at the Waffle House.

PLATE 86 John Jarrard (right) with Whispering Bill Anderson

But getting a hit wasn’t easy. “I didn’t think I was going to make it for a while,” Burch said. In fact, he came close to boarding that midnight train to Georgia, taking a regular job, and forgetting the country music business.

Jarrard’s breaks came first. His first hit song, “Nobody but You,” sung by Don Williams, was in 1983. Before it was all over, he had written eleven number one hits and scores of other tracks for most of country music’s top artists, including Alabama, Don Williams, George Strait, and John Anderson.

The number one hits didn’t come as often for Burch, but they came. In about 1984, he got a cut on an Oak Ridge Boys album that went multiplatinum, meaning he received a fifteen-thousand-dollar advance. “I was probably making that in a year,” he said, and grinned.

Later in 1988, the hits began in earnest. “The Last Resort” was followed by “Out of Sight and on My Mind,” a song performed by Billy Joe Royal. At one time, in early 1988, Burch and Jarrard had five songs, three of Jarrard’s and two of Burch’s, on the country music top-fifty list.

Burch met singer Reba McEntire when she checked in at the Hall of Fame Motor Inn, there for her first time singing at the Grand Ole Opry, and waited on her at Houston’s Restaurant later. Coincidentally, it was Reba who recorded his two number one hits: “Rumor Has It” and “It’s Your Call,” which were also the titles of two of Reba’s most successful albums. He cowrote songs on two other Reba albums, which have sold more than fifteen million copies, and has also had platinum- and gold-certified albums for other top artists. “There was a time when we were doing pretty well,” Burch said. “It started slacking off about the mid-nineties. The business was changing.”

Undaunted, he started his own publishing companies, first as Burch Brothers Music and then as Bruce Burch Music. He pitched other people’s songs as well as his own.

A few years later, Burch became creative director of EMI Music Publishing, a big, successful company. While still writing himself, Burch also worked the classic-song catalogs, arranging new recordings of old songs by such successful songwriters as Kris Kristofferson, his hero; Tony Joe White; Smokey Robinson; Dolly Parton; and Mac Davis.

Burch wrote a number of top-ten, top-twenty, and top-forty songs. But successful though he was, he sometimes seems almost apologetic about not writing more hits. “Jarrard had a lot more success than I did,” he said, “so he celebrated more than I did.”

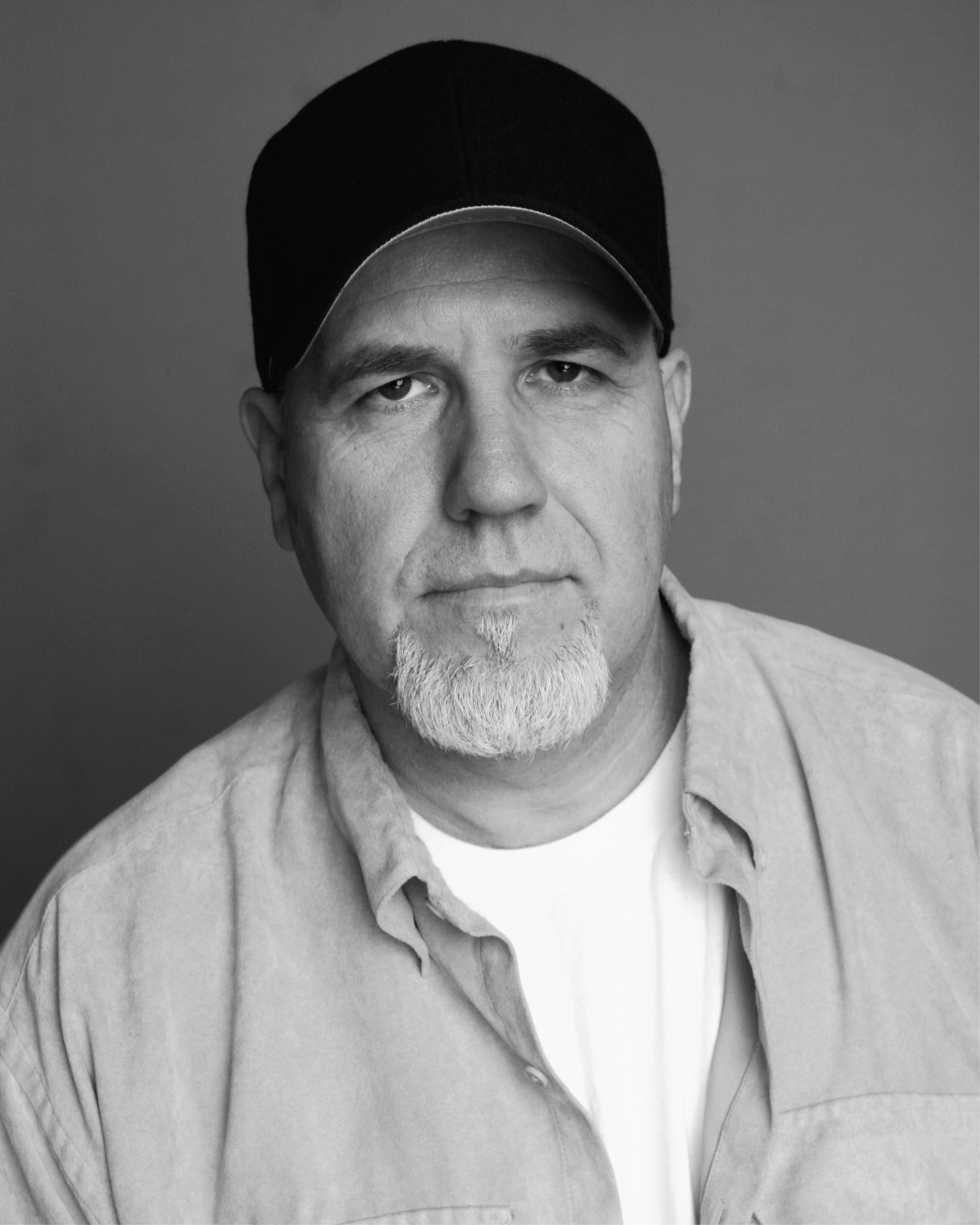

PLATE 87 Jeff Stevens

“Bruce was very generous with his talent back in those days,” said Jeff Stevens, a singer and songwriter in Nashville. “I learned a lot about the cowriting process from him and realized as I was writing with him that I had a lot to learn about the craft. Over the years, I have found Bruce to be not only a super talent as a writer but also as a teacher/mentor. Bruce has a very approachable and down-to-earth personality and is very giving.”

And Stevens wasn’t the only one Burch helped. “I have many very successful friends that in some way or another Bruce has contributed to their career,” Stevens said.

Like Burch, Jarrard also mentored other musicians, including Wendell Mobley, a singer/songwriter who moved to Nashville in the early 1990s to make it big. “I remember getting with John, as a cowriter, and that’s when it hit me that I wasn’t as good as I thought I was.”

“I don’t know why he liked me, but he liked me,” Mobley said. “He took me under his wing, man, and showed me how to do this. I am so thankful for that. I promise you I would have been gone a long time ago if it hadn’t been for Jarrard’s coaching.”

About a year after moving to Nashville, Jarrard started losing his eyesight. A diabetic since childhood, he suffered from health problems his entire life, and his vision was one of the victims. When he was twenty-six years old he had to quit his job at the Hall of Fame Motor Inn and concentrate strictly on writing songs.

“He said he could go back to Gainesville and learn how to be a blind man or stay in Nashville and learn how to be a songwriter,” said Janet Tyson Jarrard, whom John married in 1995, after his first marriage failed. “One of the things that I respected the most about him and that fascinated me the most about him was with all of the physical challenges he went through, he was the most positive person I’ve ever met.”

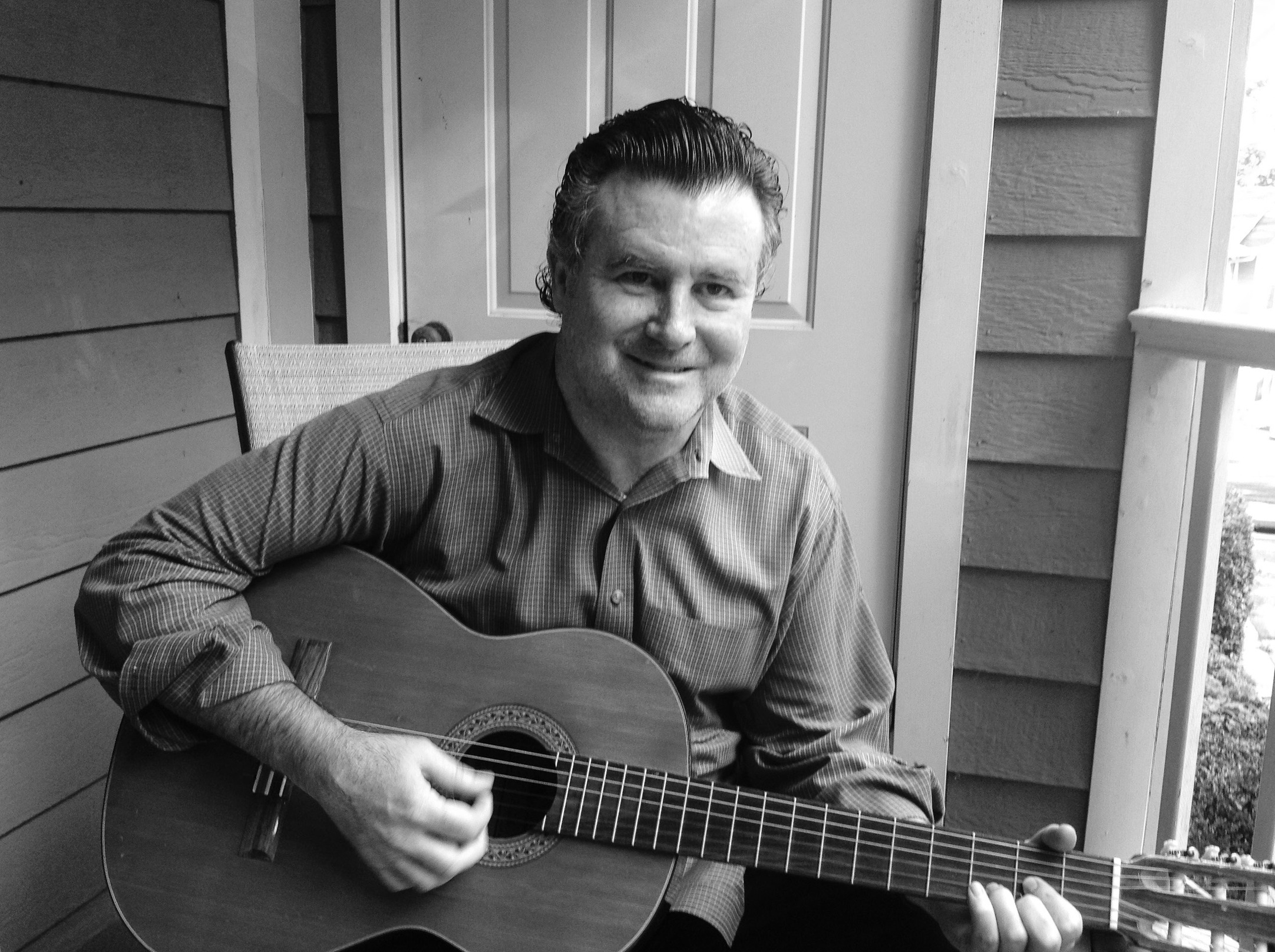

PLATE 88 Jarrard (right) picks and sings at Nashville’s Bluebird Café with legendary Waylon Jennings.

And the word “daring” should fit into that description somewhere. To raise money for the Tennessee School for the Blind, for example, Jarrard rappelled off Nashville’s ASCAP building, three stories high, in 1993. “Somebody told John, ‘You can’t do that. It’s too dangerous,’ ” Janet Jarrard said. “And John said, ‘Dadgummit, who says I can’t?’ ”

Some people might have thought that Jarrard would stop going to the office to write, because it’s not easy even for a sighted person to negotiate some of Nashville’s sidewalks. But he did it. He hired a mobility trainer to teach him how to get around using a cane. “It was superhuman,” Burch said. “He walked Music Row every day. He was a legend in Nashville. He’d get to the office and he’d be bloodied up from running into a stop sign or something, especially when he was just learning his mobility training. He used to make himself come downtown just to get practice. It was like learning to drive in Atlanta.”

On Fridays after work, Jarrard and Mobley would sometimes find a place to drive go-carts. “He would follow me around and listen to my motor,” Mobley said, “and he would hit me in the corners and stuff and burst out laughing. He loved racing, so we had to do that all the time.”

John Jarrard loved to have fun, but songwriting always came first. Some writers would wait for inspiration. Jarrard didn’t. For eighteen years, he was with Maypop Music Group, the publishing company for the band Alabama, and he wrote there, or somewhere, every day he could move about.

“He literally said in his later years that he came to view his blindness as a blessing,” Janet Jarrard said, “because if he had not gone blind, he would not have had to make that decision to pursue music with everything he had.”

Burch moved on with his career. He had taught a music-publishing class at Belmont University in Nashville and enjoyed it. So in 2005, he approached officials at the University of Georgia, his alma mater, about starting a music-business program. They agreed, but said they needed financial support. Burch raised the money himself.

Five years later, he started a similar program at Kennesaw State University in Kennesaw, Georgia, and again raised the start-up money. In 2012, he moved back home to Gainesville, where he taught four courses at Brenau University: entertainment management; careers in music, sports and entertainment; event planning; and an adult-education class in songwriting.

In the 1990s, Burch and Jarrard teamed up for a series of benefit concerts in Gainesville, raising money for local charities. The concerts became more popular every year. But Jarrard’s health was declining rapidly. Besides losing his eyesight, his kidneys failed, and he underwent kidney-transplant surgery. That kidney failed in 1995, about a month before he and Janet were married. He went back on dialysis for eighteen months and received another kidney in 1997. He lost both legs in below-the-knee amputations and part of a finger on one hand, spending most of 1997 and part of ’98 in and out of the hospital.

Bruce Burch had his own health problems. In 1991, he was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and underwent chemo treatments. Those treatments are over, he hopes, but he still receives infusions every three months to boost his weakened immune system. He is susceptible to infections and came down with double pneumonia in 2014. CLL is not curable, he said, but is treatable.

Now divorced, Burch is a proud grandfather of four and still writes some but also spends time helping others write. Low-key about his own accomplishments, he likes to brag on former students who are now doing well.

Writing songs is hard to teach because the really good writers, like athletes, are born, not made, Burch explained. He is not a born writer, he said. He works hard at it. If he didn’t make it as a songwriter, he figured he could teach and coach football. But writing songs was what he loved to do. As a young man, he loved the storytelling songs of Kris Kristofferson, so one day, he picked up his brother David’s guitar, learned three chords, and strummed a few songs by Kristofferson and Hank Williams. “You didn’t need but three chords for most of Williams’s songs,” he said.

PLATE 89 Bruce picks it out.

The worst thing that can happen to a songwriter is to come up with a great idea and then forget what it was. After he lost his sight, Jarrard always carried a hand Dictaphone with him as he made his way with a cane, and later prosthetic legs, from home to office and back. Burch keeps a pad and his cell phone handy for the same purpose.

The best songs, of course, come with a message that touches people, sometimes in a way the songwriter didn’t expect at all. When Jarrard and his cowriters, Lisa Palas and Will Robinson, were writing “There’s No Way,” an Alabama hit, they thought they were turning out a traditional man/woman love song. But Tony Franklin Moore of Munford, Alabama, thought of his mother.

Tony, you see, was born in 1972 with spina bifida, which develops when the bones of the spine don’t form properly around a baby’s spinal cord. Burch wrote about Tony in his book, Songs That Changed Our Lives.

“My parents were asked by the hospital staff if they would put me in a nursing home,” Tony told Bruce in 1995. “They said I wouldn’t live anyway, but my parents kept me. The nurse told my parents that if they kept me, I would live longer if I had lots of love.” And then one day he heard the song “There’s No Way.” To most people, it was indeed a traditional love song. But to Tony, it was a song to his mother.

“You see, I’d lay my head on my mother’s chest when I was little,” Tony said, “and she would tell me how much she loved me. All my life, she has told me over and over how proud she was of me and how much she loves me. I sure do feel her love in the chorus of the song.”

Jarrard met Tony in 1985 at an Alabama concert in Northeast Georgia, and they became friends, friends who were there for each other over the coming years. They inspired each other. “When John reached his lowest emotional state,” Burch wrote, Tony Moore’s inspiration kicked in. Whenever he felt robbed, he would think of Tony. “I knew that no matter what I was going through, Tony had been through worse,” Jarrard told Burch.

John Jarrard died on February 1, 2001. He was forty-seven years old. Two memorial services were held, one in Nashville, another in his hometown, Gainesville, Georgia. Some of his fellow songwriters and singers were there in Nashville. “I didn’t make it through very well,” Wendell Mobley remembered, “but I was there. I was a mess.”

About two months later, Jarrard’s ashes were scattered near what the family called Jarrard Creek, at the base of Blood Mountain in Northeast Georgia. Jarrard, already blind, had climbed that steep mountain at night with his brother, Tom, and other family members and friends.

Not long after Jarrard’s death, the late Mike Banks approached Burch about continuing the benefit concerts that he and his friend had performed in the 1990s. Burch was reluctant at first. But then he reconsidered. Perhaps this would be a good way to remember his buddy and to help worthy charities at the same time. That same year, Burch got together with several Gainesville friends, among them Banks, Philip Wilheit, Charlie Strong, Jim Mathis, and Allen Nivens, and formed the John Jarrard Foundation. Since that time, the foundation, holding one major concert every year, plus several smaller events, has raised nearly two million dollars for charity. The sixteenth annual concert was held in September 2017 on the campus of Brenau University, where Burch taught.

Songwriter Jeff Stevens was one of the performers in 2015. “I came down to Gainesville for two reasons,” he said. “Number one, because I knew John Jarrard and admired his talent and fortitude when faced with illness, and I wanted to support the foundation, and number two, Bruce Burch was the first Nashville songwriter that I wrote with, and I wanted to repay him for that.”

Wendell Mobley was there, too, and also performed at the first concert after Jarrard’s death. “I still write like he wrote, his process,” he said. “He taught me to close my eyes and drool and think for four hours. I still think about him when I’m writing. What would John do? How would John do this or look at this?”

Now, every September, successful songwriters travel to John Jarrard’s hometown to sing and play, not for money, just for a friend they remember, and for Bruce Burch, his best friend.

“I see the benefit concerts as an extension of his life, the way he lived his life,” Janet Jarrard said. “Whatever that spirit of transcendence with John came from, I think it’s been passed along to this event. It’s been so beautiful to watch it happen.”

In late 2016, Bruce Burch resigned his teaching job at Brenau University and moved back to Nashville to be near his four grandchildren and, of course, to write country songs.

Jarrard was inducted into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame in 2010.

It’s been more than fifty-seven years, but Burch still remembers their first meeting. It was on the playground of Enota Elementary School in Gainesville. “He said, ‘Hey, Johnny.’ He thought I was Johnny Yarbrough, another friend. I said, ‘No, I’m Bruce.’ We had just moved to Gainesville from Hiram [Georgia], and John Jarrard was the very first person I met.”

So, in the beginning, it may have been a friendship by accident. But in the end, after all the dreams, the love, the heartaches, the laughter, the failures, the triumphs, it’s actually a country song waiting to be written.