Inventing a Time Machine and Other Adventures

Emory Jones, the great storyteller

ARNOLD DYER’S young daughter Krista couldn’t believe what she’d just read in the local newspaper. “Daddy,” she said, tears in her eyes, “they’re going to move Yonah Mountain to Atlanta and put in a lake where the mountain is.”

“Let me see that newspaper,” Dyer said. “Honey, look who wrote that story.” The byline over the column, printed about fifteen years ago in the White County News of Cleveland, Georgia, was that of Emory Jones. Krista had nothing to fear, her father assured her. It was just another one of Jones’s tall tales.

That’s Emory Jones’s story of what happened that evening, but that’s not exactly the way Dyer remembers the incident. “But,” Dyer said, “let’s go with Emory’s version. He’s got a better memory than me, and he’s a better storyteller.” In fact, Emory Jones is a better storyteller than most people. If you don’t believe it, talk to his friends or to his wife, Judy, or to the publisher of his local newspaper. Better yet, sit down with him in his rustic home, nestled nicely in the woods two-thirds of the way up White County’s Yonah Mountain, and just listen. The mountain, by the way, hasn’t moved an inch.

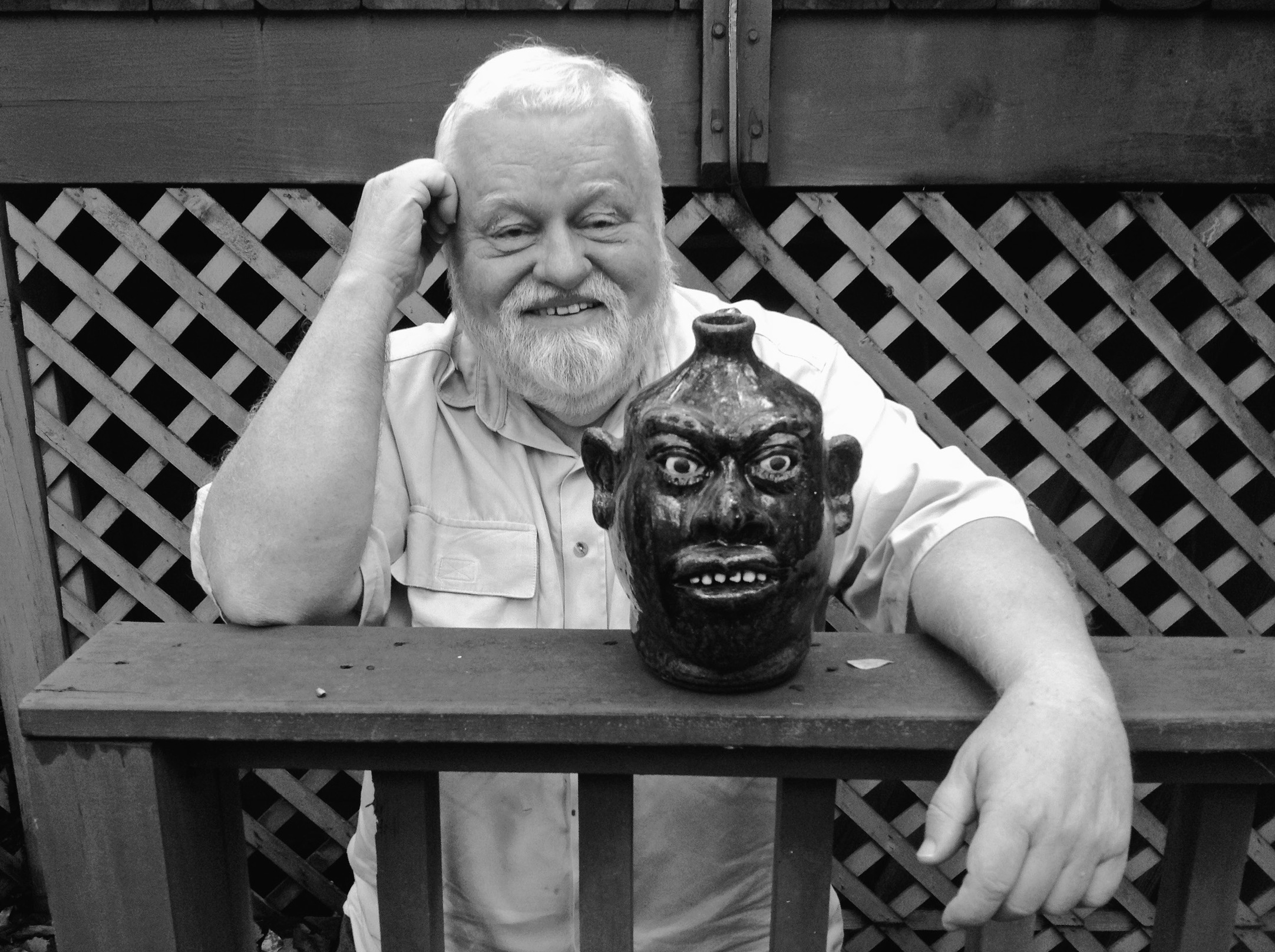

“The Joneses like to talk,” Emory said. Jones’s daddy was Dennis Jones of Banks County, Georgia; his mother was Wirtha Meaders of the famous family of potters who lived in the Mossy Creek section of White County. “The Meaderses are quiet people. The typical Meaders can go in the woods for six months and never speak to anyone and be happy,” he remarked. Emory is definitely more Jones than Meaders. But he does love pottery. As we talked in his home, sixty-one sets of funny-looking eyes looked down on us from a shelf that holds Jones’s collection of face jugs.

PLATE 93 A perfect face for a jug, but that’s not his face.

“I tell people who are interested in starting a pottery collection that pottery is like heroin,” Jones said. “You may start with a little pot now and then, and pretty soon you’re addicted to the hard stuff.” Mostly, it seems, Jones is addicted to having fun. A few examples of his sense of humor:

-

Jones wrote a newspaper column saying he didn’t think it was right for Sarah Palin to run for vice president of the United States. “If we let people from Alaska run for office,” he said, “before you know it, there’ll be people from Hawaii and New Mexico wanting to run.” One reader took Jones seriously and complained to the newspaper.

-

He advocated changing Georgia’s state bird from the brown thrasher to the chicken. “What’s a brown thrasher ever done for the state?” he wanted to know. The chicken is big business.

-

A lot of people have conversation pieces in their homes, but very few build covered bridges in their yards. Jones did. Its only purpose, other than sparking conversation and providing a place for graffiti, is to house a 1986 Ford F-150 pickup, with forty-two thousand actual miles on the clock, that belonged to his uncle Howard.

“Jones obviously loves storytelling,” said Billy Chism, a longtime friend and the former editor and publisher of the White County News, which published many of Jones’s tongue-in-cheek columns: “You can call Emory up and ask him to go to lunch, and he’ll tell you three stories before you hang up. That’s just in his nature. He has to tell a story just to say hello.”

Emory Mitchell Jones was born on May 7, 1950, in the old Downey Hospital in Gainesville, Georgia, and was taken home to Banks County, Georgia, where his father grew up. The Joneses were planning to settle for good in that rural county; in fact, Emory’s father was building a house there for his young family when tragedy changed everything.

Dennis Jones and some of his friends and relatives had been blasting out a well on the new homeplace when Bill Griffin, a friend from nearby Lula, went down into the well to remove loose rocks. A short time later, others at the top saw that Griffin had passed out at the bottom of the well, which at the time was about thirty feet deep. They knew he had been sick at work that day, and they thought his passing out was due to sickness. Jones went down after him.

“He took a rope,” Emory said, “and put it behind Mr. Griffin’s shoulders and looked up at Leonard Jones and my mother and asked, ‘How do you think I should tie this knot?’ And he just fell over.” Both men died. Emory was eleven months old.

The men were using a gas-powered blower to force dust and fumes out of the well, but the blower’s exhaust pipe was defective. It had rusted off, causing carbon monoxide to flow back into the well.

After his father’s death, Emory and his mother moved to live with his granddaddy, Wiley Meaders, oldest of the Meaders potters of White County, on a farm connected to the old Meaders home place and pottery shop in the Mossy Creek section of White County. But it was a good walk from where the school bus picked up children. Granddaddy didn’t want his grandson walking that far, so he built another house close to the road.

“Granddaddy had made a little money in the chicken business,” Jones said, “so he built this brick ranch house and spent five thousand dollars on it. People came from all over to see that five-thousand-dollar house.”

Jones also spent a lot of time at the home of his aunt and uncle, Lenore and Howard Chambers, in nearby Clermont, Georgia. “I just loved being out in the pasture with Uncle Howard, feeding the cows and chickens, going to cow sales, and stuff like that.”

In fact, Emory Jones the little boy thought he was going to be a farmer until he “realized there was a lot of work in it.” So Emory Jones the teenager found other opportunities in agriculture. At White County High School, he did about everything that could be done in the Future Farmers of America (FFA) chapter. He showed cattle and pigs. He gave speeches. He served as chapter president and state secretary. He even received the American Farmer Degree, the highest degree given by FFA.

He told stories, too, of course. “I think I’ve always told stories,” he said. “Even in high school, I enjoyed public speaking. I’m not saying I was good at it. I would just get up and tell stories. You can only talk to one person at a time when giving a speech. That set me at ease.”

FFA also afforded him a trip to England through its Work Exchange Abroad program. He worked for four months on a farm in the county of Herefordshire, where Hereford cattle originated in the mid-1700s. His first day on the job, the farmer, whose name coincidentally was Hereford, assigned him a chore he didn’t quite understand. “I don’t know if he was messing with me or not, but the first day I put on work clothes and went out to work, he said this: ‘Go get a spanner [a wrench], go out to the lorry [the truck], look under the bonnet [the hood], and check the petrol transport [the fuel line] for stoppage [a leak].’

“I didn’t have a clue,” Jones said. “I went to England because I thought we wouldn’t have a language barrier. The other FFA folks who went to Germany and France dealt with people who spoke perfect English.”

After high school, Jones spent a year goofing off, he admitted to it, at Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College (ABAC) in Tifton, Georgia. “I had a grade point average of 1.4 and a [draft] lottery number of thirty-four,” he said. He loved airplanes better than school, and flying better than marching, so he spent his next four years in the US Air Force.

Even in the service, Jones used his storytelling talents to win and entertain friends. “I remember sitting up on the top bunk and people coming in and me telling stories from back home,” he said. “I read correspondents’ columns to the boys from New York and Chicago: ‘So and So is visiting So and So.’ I made up a character named Wayne, and a lot of Wayne was Emory. People always wanted me to tell a story or a joke.”

Jones emerged from the military a changed, more mature man. He entered the University of Georgia, where he majored in agriculture journalism and graduated with a 3.9 grade point average, considerably better than his 1.4 at ABAC.

After college, in 1976, Jones landed the perfect job for someone who likes to write, shoot the bull with people, and travel. He went to work in the public relations department at Gold Kist, Inc. “It was a great job, a great company, like family, and I had a company car, making ten thousand a year. I just went around interviewing farmers, taking pictures, doing stories.” At Gold Kist in Atlanta, he met his love and soul mate, Judy Gee, whom he married in 1978.

The Joneses lived in Atlanta for twenty-seven years before they eventually bought their getaway cabin, as Emory calls it, on Yonah Mountain in White County. “I told a Realtor that I want a place where I can run around the house naked if I want to.” And when they were shown the house on Yonah, they knew this eventually would be home. “We hadn’t even been in the house,” Jones said, “and Judy said, ‘We’ll take it.’ ”

For several years, the couple spent their weekdays in Atlanta and their weekends on the mountain. Then, in 2000, they moved to White County permanently, and Emory commuted to Atlanta for the next three years. “I didn’t hate Atlanta,” he said, “but it was a tremendous relief getting out of Atlanta.”

Emory Jones retired from the Atlanta job in 2003 and started his own ad agency, working out of his White County home. Today, he is anything but retired and rocking on the back porch. He’s always working on a project, a documentary film, a book, a column, a speech, anything that involves telling stories. Whatever he’s doing at home, his fifteen-year-old cat, Sylvester, the only cat in the county that can chase a German shepherd up a tree, will be at his side. “I never liked cats until Sylvester showed up one day and stayed,” Jones said.

And Judy was there, too, unless she was at work at Yonah Mountain Treasures, a store north of Cleveland that sold everything from pottery to puzzles. “It’s been an adventure being married to Emory,” she said, standing behind the counter of the store, which since has closed. No, she said, she doesn’t have her husband’s creativeness. “We don’t have time for both of us to have that talent. It takes all our time to keep up with his ideas. Sometimes we don’t see eye to eye on how to sell things. He’s the relationship person. He gets out there and talks and talks. I’m not. I’m going to be over here doing the bookkeeping part of it.”

PLATE 94 Emory in his time machine

But Judy Jones sells herself short on creativeness. For Emory’s fiftieth birthday, she had twenty-two women and two men dress up as Dolly Parton for a party she threw in his honor. Said Emory, “I missed most of it because I passed out when twenty-four Dolly Parton look-alikes yelled SURPRISE!”

One strange piece birthed by the man with the snowy-white hair and beard and the sleepy blue eyes used to sit uncomfortably in the middle of the Yonah Mountain store. It was Emory Jones’s time machine. “I was kind of concerned about the time machine,” Judy said, smiling. “I didn’t know if that was going to work out. But he did it.” Yep, he did it, all right. He did it with the help of the late Ludlow Porch, a radio personality known throughout Southern Appalachia for his slow, down-home voice and humorous stories.

“I asked him if he would help me write a history book that involved a time machine,” Jones said. “What do I have to do?” Porch asked. “First, you have to tell me what a time machine looks like.” Porch said, “Give me a week.”

This time machine, Porch decided, should consist of two johnboats, one turned upside down on top of the other and held together by four cedar posts. It requires photos of John Wayne and Dolly Parton and is powered by a goat running on a treadmill and facing a basket filled with overripe rutabagas with an “ovulating” fan on the back to blow away the pixie dust. It’s operated by the Fleebish system. “We started with Fleebish One, worked up to Fleebish Eight, and decided to settle on the Fleebish Seven,” Jones said. “The only difference was the Eight had a horn, and Seven didn’t have a horn.”

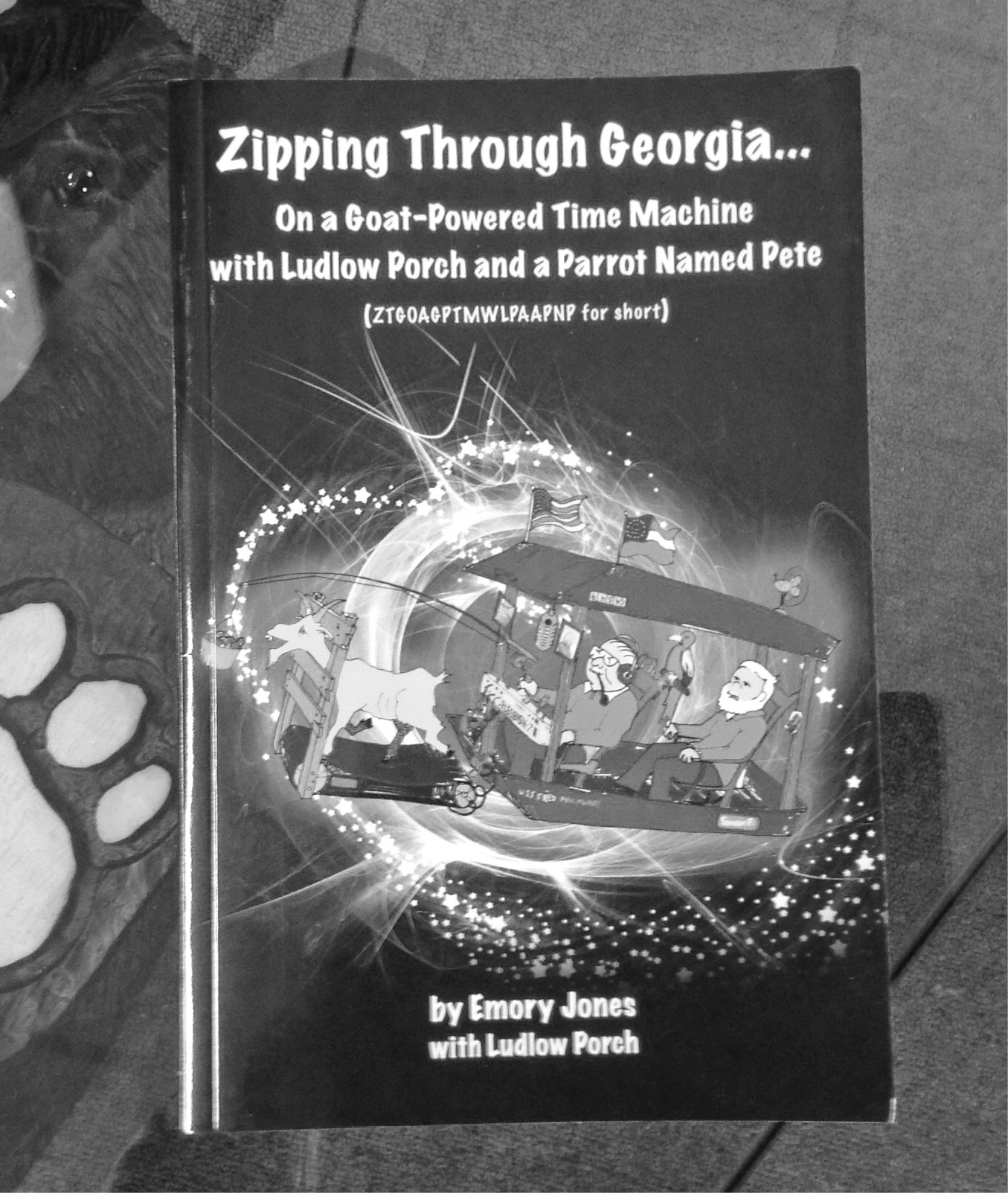

PLATE 95 Zipping Through Georgia…one of Jones’s books

Jones built the full-size, workable model, named the USS Fred MacMurray, and equipped it with two rocking chairs from a Cracker Barrel restaurant. “This is the only time machine in Georgia that’s publicly operated,” Jones quipped. “We could afford permits for only intrastate travel. We charge just a hundred thousand dollars a year, but you don’t have to pay until you get back.” Customers need only to show proof of insurance and furnish their own goat, which must get the treadmill up to White Max–warp speed, which is three miles per hour.

The result of it all was a book written by Jones and a recording of the story narrated by Jones and Porch. It’s titled: Zipping Through Georgia…On a Goat-Powered Time Machine with Ludlow Porch and a Parrot Named Pete, or ZTGOAGPTMWLPAAPNP, for short. Jones read the entire book to Porch, who was in declining health, and the radio man responded, “This ranks right up there with The Grapes of Wrath and some other book I read one time.”

At first glance, some people think it’s a children’s book, but it’s really for adults with a sense of humor and a love for Georgia history. “The history is very real,” Jones said. “We tried to go back to 1733 and see Oglethorpe land on the coast of Georgia, but we didn’t set the hob knob right and the first time we go out, we land on top of Stone Mountain in 1920, when they’re doing the carving.”

The machine also visits Kennesaw, Georgia, where the time travelers saw Yankees steal the Confederates’ train The General during the American Civil War. They witnessed, among other events, Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, being captured in Irwinville, Georgia; and even the Goat Man clopping through Royston, Georgia.

“We had a lot of fun with the book,” Jones said. “Some people get it; some people don’t.”

Billy Chism said he liked the audio version better than the book. “The audio really gets into the characters, whether it was Emory talking or Ludlow Porch talking,” he said. “Emory had all these different voices that he would project, but the whole thing was so full of tomfoolery that he tickled himself doing it, and it came through in the audio.”

Said Arnold Dyer, Jones’s closest friend for fifty-eight years, “He’s as full of crap as a Christmas turkey. But he’s sincere. I’m pretty much in awe of Emory.”

Awesome may well describe everything Jones accomplished before and after retirement. He was one of a hundred people chosen to photograph rural America for a book titled Country USA; he and a White County historian, the late Shirley McDonald, published a book called White County 101, about things to do, know, and love about the county; he also wrote a book, and, with videographer David Greear, produced a video titled Distance Voices: The Story of the Nacoochee Valley Indian Mound, which brings to life the story of a prehistoric Indian burial mound in the county, its builders, and the valley that spawned it; he turned out Heart of a Co-op, a book on the history of Habersham Electric Membership Corporation (HEMC), with sponsorship from HEMC; and he wrote the script for Experience Northeast Georgia, a recorded guide, narrated by the late artist John Kollock, to seventy-five places to visit in the region.

More recently, Jones wrote a novel, The Valley Where They Danced, a story based on a legend about a medical doctor who moved to White County from middle Georgia after World War I and married a local woman. The book, which has been well received, captures the dialects, words, and sayings of the era, generational knowledge that eventually will be lost. Thanks to Jones’s versatility, the book became a play, first performed in June 2017 at Piedmont College in Demorest, Georgia.

Jones’s latest project is a film documentary of the old Tallulah Falls Railroad, which operated in the Northeast Georgia Mountains from 1854 until 1961. With David Greear as videographer, the documentary features local people as narrators, most of them from nearby Rabun County.

Emory Jones isn’t done yet. His plans include writing a book called The Well, about the accident in which his father died; a sequel to The Valley Where They Danced; and another screenplay and maybe starting another business, now that Yonah Treasures has closed. What kind of business? The Joneses aren’t sure yet.

One of her husband’s favorite sayings, Judy Jones said, is “It’s something all the time.” If Jones is not collecting pottery (he has reduced his collection from about five hundred pieces to half that) or working on a book or a documentary or a speech or a satirical column for the newspaper, you might find him taking one of his kinfolks to the doctor or running an errand for a friend. It’s not unusual to hear a good word about Emory Jones. “He’s always thinking about somebody else and doing for somebody else,” his wife said.

Deep down, said Chism, his former editor, Jones is just a good guy. “And because of that, he can’t help but do good things and write good things. That’s where it all comes from: There’s an inner goodness about him once you get past all that humor.”

But don’t think that anyone will get past all that wit. It’s in Jones’s nature to conjure up humor when it’s appropriate. Sometimes, of course, conjuring isn’t needed. Circumstances themselves are often enough for a laugh. Take, for example, the time Dyer was accompanying Jones on a flight from North Georgia to Tifton, Georgia. Jones was the pilot and Dyer was the sole passenger. But after a while in the air, Jones said he felt sick and might throw up any minute. He asked Dyer to take over.

“Just keep that little airplane on the control board level, and we’ll be all right,” he told his friend. “Well, we got close to the airport in Tifton,” Dyer said, “and I said, ‘Emory, you either got to puke, jump out, or we’re going to crash, because I ain’t landing this thing.’ ” “Ah, I feel better now,” Jones said, and took over after faking his friend into believing he was ill.

When you’re with Emory Jones, his wife said, “you’re always laughing. He gets in so many situations. Sometimes you can’t believe that one person could get in that situation and then get out.” And nearly every one of those situations has been turned into a story of some kind.

It might be the story going around that the state planned to dig up Yonah Mountain, move it to Atlanta, and put a lake in its place. Have you heard that one? Let Emory Jones tell it to you some time. He will certainly oblige.