Dr. C. B. Skelton of Winder, Georgia

Practicing medicine and sharing humorous stories

IT WAS MIDMORNING on the day before his eighty-ninth birthday, and Doc Skelton was sitting in his living room with a hot towel across his face to soothe his weak blue eyes. He’d been up for several hours, watering his tomato plants, tending his okra, piddling.

“Are you not going to get dressed?” his wife, Fran, asked, noticing that he had not changed his dirty shirt after working outside or combed his hair, even though he was expecting company. “No,” he said, “I’m going to be dressed just like this.” “Well, are you going to zip up your pants?” asked Fran.

The scene sort of describes Charles Bryant “Doc” Skelton of Winder, Georgia, a man comfortable in his own skin, even if it’s dirty. No use pretending, no use putting on airs, no use dressing up for an interview. “I’m just me,” he said later, during the interview. “I always have been just me.” But just being Doc Skelton is quite a story.

Myles Godfrey, a longtime mutual friend and owner of The Barrow Eagle newspaper until he sold it, is well familiar with Doc Skelton, his story, and his storytelling. “People who know Dr. Skelton’s background are aware that he is an exceptional person,” he said. “He finished high school, earned a college degree, and completed a tour in the Army, all before he turned twenty-one. Then he was accepted at Emory Medical School, graduated, and became a doctor when he was twenty-five. All that proves to everyone he is special, except to him. He does not think of himself that way at all.”

Doc Skelton is a man of many interests and talents. He is a Bible teacher, local missionary, speaker for Gideon’s International, singer, autoharp player, humorist, community leader, family man, philosopher, and optimist, but most people know him as an engaging storyteller. In this role, he’s written songs, poems, and five books, in addition to the many stories he’s famous for sharing with friends and family. Godfrey remembers the day his daughter, Isabel, came home talking about Doc’s speaking to her school’s sixth-grade class. “He told stories, recited poetry, played the autoharp, and sang,” he said. “The kids were enthralled.” Isabel still remembered Doc’s stories and one particular poem five years later.

So what does it take to become a good storyteller? Doc struggled a little with his answer, not because he doesn’t know, but because storytelling comes so naturally to him, it’s hard to put into words. “Well,” he said, finally, “a fellow has to know what he’s talking about, and yet you need to be able to embellish without it looking like embellishment.” Many of his stories come from decades of doctoring in Barrow County, Georgia, and don’t need a lot of embellishment. Other stories go back to his childhood, back when he was plowing a mule named Blackie. Anybody who ever plowed a mule knows that you talk to the animal as though he were human. And sometimes you use bad words to get his attention. But one morning, Doc harnessed Blackie and then told him, “Blackie, I’m a Christian now, and I’m not going to talk bad to you anymore.” Blackie was not impressed.

“That mule was so cantankerous and my plow caught on so many roots, I could not hold my temper or my tongue,” Doc said. “Before I had plowed two rounds, every evil word I knew had come out. I couldn’t believe my ears. ‘Christians don’t talk that way,’ I thought. Frustration, anger, disappointment, and doubt were my emotions of the moment. Every day, I vowed to do better, and every day, I failed. Fearing the ‘rod of correction,’ I dared not tell Mother or Daddy. Months passed, but the problem remained. Finally, taught by a mule, the truth dawned on me. One can only live the Christian life in God’s strength—never in our own strength. It didn’t hurt that we finally sold Blackie.”

In his earliest years, Charles Bryant Skelton thought his first name was Red, and this was long before comedian Red Skelton became famous. “My hair was red, and I was [called] Red from birth,” he said, chatting over coffee at the Skelton home near Winder. “My first report card in 1931 came out as Red Skelton. They tell me that my teacher asked me, ‘What is your name?’ And I answered, ‘Well, my name is Red, but sometimes they call me Charles.’ ”

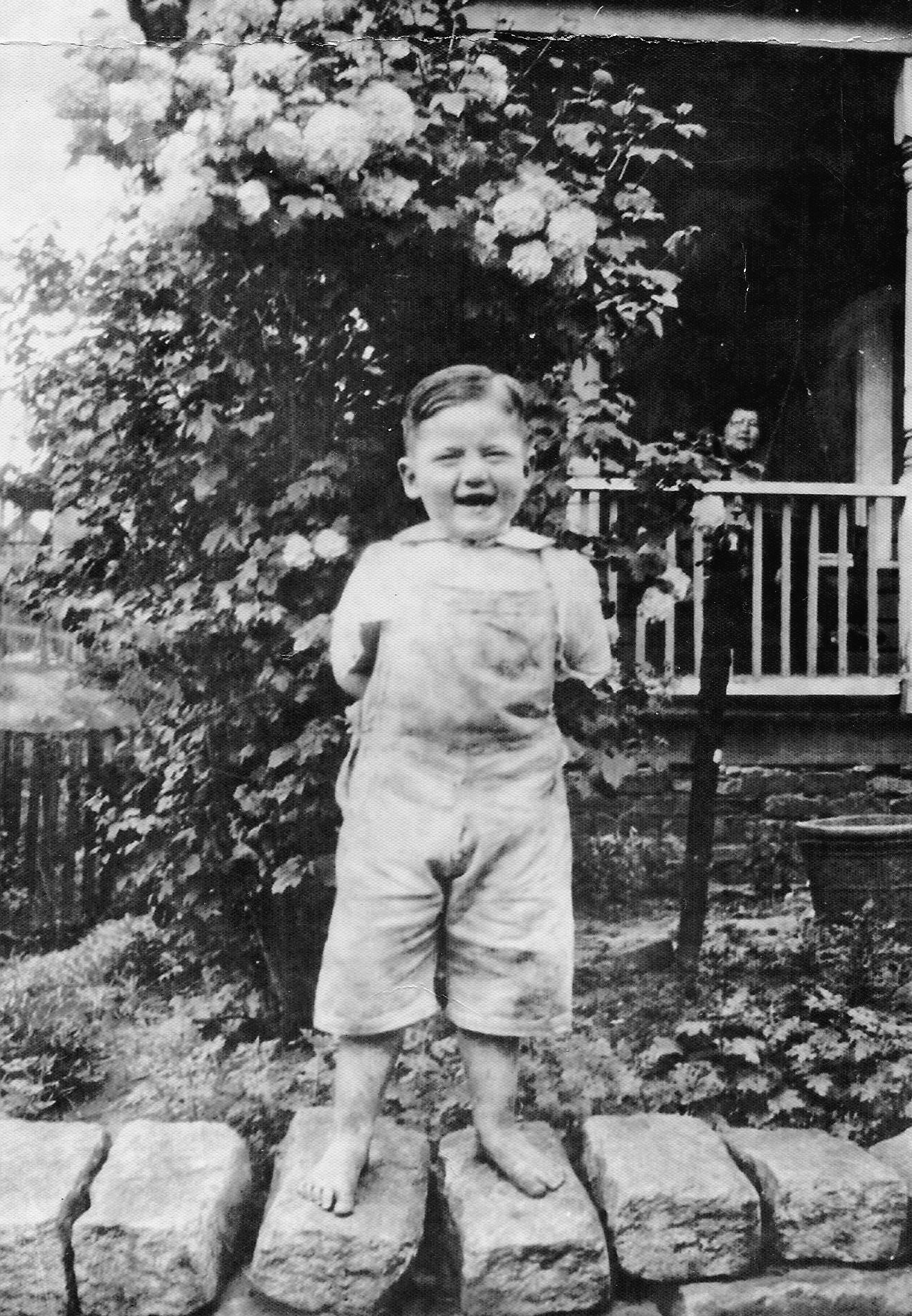

PLATE 97 Doc as a happy child

This healthy, red-haired boy was born at nearly fourteen pounds, the tenth of a dozen children sired by Newton Anderson Skelton. Five of the children had been born to the former Ethel White, and after her death, Doc’s father married the former Rosa L. Turner, who produced seven more. Doc was her fifth, born in 1926.

Three years later, the Great Depression descended on the Skeltons’ family home and on the nation. Being a man of compassion, Newton Skelton had signed bank notes for a couple of men who later went bankrupt, leaving his family broke. The Skeltons eventually lost their home and became tenant farmers, moving from rented farm to rented farm and breaking new ground with a mule-drawn plow. Doc Skelton became a plow-hand at eight years old and once plowed land that would become part of the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. His father worked as a streetcar conductor, and money was tight. “I didn’t ask my dad for a penny to buy a pencil with,” Doc said. “I’d go through the school yard and I’d find a pencil somewhere.”

Neither would he request a penny to buy candy, but he learned to use poetry and boyish guile to sometimes get it for free at a little store close to his home. “I had not learned to write,” he said, “but I made up my first rhyme and put a tune to it and sang it to them: ‘Charlie, he’s a good little boy / Charlie, he’s a dandy / Charlie, he’s a good little boy / And he likes striped candy.’ ” He got his candy sometimes, “but most of the time,” he said, “they were as poor as we were.” So Doc Skelton got his start in poetry out of necessity.

Doc idolized his brother Jimmy, the sixth of the dozen little Skeltons. Jimmy was a great athlete and a man of faith. And when he told his parents he wanted to be a missionary to Africa, Doc declared he wanted to be a medical missionary in Bolivia. “I had no idea where Bolivia was,” he said. “In a way, I was copying my brother, but I also knew in my heart I had to become a doctor.”

Doc graduated from high school at age fifteen and then worked his way through Mercer University in Macon, Georgia. He had set his sights on medicine, but with World War II raging, the US Army had a different vision for him. At that time, the Navy was educating men for different types of professional work, including medicine, through a program called the V-12. Doc had tried to join the program, but a minor deformity, one he couldn’t explain graphically to members of the Women’s Missionary Union, disqualified him, and the Navy said no.

The Army, however, said yes, even though Doc had already been accepted to medical school. “I was supposed to be ineligible for the draft, but the Army guy said, ‘You’re in the Army now.’ ” It was ironic, he said, that he was not qualified to attend school in the Navy, but he was qualified to lead an Army platoon into combat.

At the encouragement of his captain in basic training, Doc ended up in Officers Candidate School. He had gotten a college degree at eighteen, and it was his duty to become an officer and a leader, the captain said. So Doc completed OCS and became an infantry officer. He was training a platoon of men to invade the islands of Japan, but then US planes dropped atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Doc Skelton became expendable. He was sent to Europe to lead a crew that traveled from little burg to little burg, locating the graves of American servicemen in France, Germany, Austria, and part of Italy. A few days shy of two years of service, he was discharged and returned home.

Turned out, the Navy had done Doc a favor by not accepting him. The program that would have trained him for a career in medicine had folded; he would have been left with no outside financial support after two years in med school. But the GI Bill had passed Congress, and Doc hitched a full ride as an Army veteran. His education at the Emory University School of Medicine was paid for. “I am probably the most blessed man who ever existed,” he said more than once.

While in med school, he married Nora Louisa Hart, who in rapid order would present him with five daughters. He had the perfect squelch for people who kidded him about living in a house with six women: “If the Lord thinks a home needs a man in it, he sends one.”

Asked how many babies he delivered as a family-practice doctor, he said, “I didn’t keep up with the number, but when I was an intern and assigned to OB in Louisiana, on one occasion I signed twenty-five birth certificates in twenty-four hours. We didn’t have room for all of them. We put them butt to butt on the beds and sent them out the next day, which was unheard of at that time.”

In 1953, the Skeltons moved to Winder, where Doc began his family practice on July 5. For the next forty-two and a half years (he retired the last day of 1995), Skelton was Doc to everybody in the county. At one time, he did it all: orthopedics, surgery, obstetrics, and even anesthesia. He made house calls and developed relationships that have lasted for decades.

“I pledged to my patients that whatever time you need is what time I’ll give you,” Doc said. “My office girls didn’t like that philosophy that much. If I had a patient in the hospital that I was worried about at night, I’d get up out of bed and go to the hospital and do everything I knew to do. And once I’d done everything I knew to do, I’d go home and go to bed and not worry anymore.”

One year, during a severe flu epidemic that nearly paralyzed the town, he arrived home for dinner about ten at night. He was tired and irritable and feeling sorry for himself. “Nora met me at the door, not with dinner, but with a list of three more house calls to make that night,” he said. “Disgustedly, I complained, ‘By the time these are finished, it will be eleven o’clock and the train should be coming through town. Maybe I should run in front of that train and let you get a husband who will stay home with you sometimes.’ Nora replied in her sweetest voice, ‘Honey, if you’re going to do that, please take the old car.’ ”

Nora Skelton died in 1987, and Doc later married “Penny” Emory Morris, a widow. Penny died in 2011, and in 2013, he married Fran Peeples Lynch, whose husband had died several years earlier. “I’ve had three absolutely fabulous ladies in my life,” Doc said. “I didn’t strike out once.” He describes Fran as “Fran-tabulous.” But he didn’t stop there: “Fran is very pretty; she’s one of the most capable people I’d ever seen; she’s energetic and she helps everybody.” Theirs is one of the city’s love stories.

Doc enjoys a good love story, obviously, and in one of the five books he has written, A Simple Seller of Noodles, he tells what he calls “the greatest love story I’ve ever heard of.” It’s the true story of SamSan, a refugee from Cambodia who, along with nine members of his family, was sponsored by the local First Baptist Church, Doc’s church at the time. Doc chaired the sponsoring committee. After several years of menial labor, SamSan opened a restaurant in Winder.

PLATE 98 Doc and Fran Skelton at home

Today, Doc Skelton spends considerable time in front of his computer. He might be writing one of the poems that he emails to several hundred recipients every week. For years, Myles Godfrey published Doc’s poems in The Barrow Eagle.

“When I was first approached about printing Doc’s rhymes,” he said, “I was very hesitant. I was aware that every community is awash with amateur poets, and I feared a deluge of submissions from folks who would expect publication. Then I read the samples I had been given. Some were inspirational, with messages that would resonate. Some were sad, but many were funny—no, hilarious. I decided to print them.”

Here are some of Doc Skelton’s favorite humorous stories. And they’re all true. Some of them were adapted, with permission, from his book titled Dirty Laundry Don’t Take No Doctor’s Orders.

Almost everyone called him “Snake,” not Lonel, his real name. It must have been because of his thin face and somewhat beady brown eyes. He worked on the construction crew building the Winder-Barrow Hospital and then in the hospital for many years as an orderly. One day, Snake entered a patient’s room to give a “four H” enema, which meant one that should be “high, hot, a heck of a lot, and the patient should hold it.”

The Director of Nurses knew both Snake’s whereabouts and his assigned mission, but she needed to speak to him. She felt her message for Snake could not wait until his task was complete, so she went to the patient’s room to have the conversation. We had an intercom system, but for some reason, she chose not to use it.

The doors to our patients’ rooms were heavy enough to be virtually soundproof, so our intrepid Director backed up against the door just enough to open a tiny port for sound to pass through, but not enough for her or anyone else to see inside the room. This accomplished, she called out, “SNAKE!”

Meanwhile, at that precise moment, Snake had inserted the enema tube into the patient’s backside and begun the flow to get his business done. But with the sound of the woman’s voice calling “Snake,” seemingly in the room, our patient gave a startled jump and pulled out the enema tube. The contents of the enema bucket, as well as those emitted from the patient, were strewn all over the patient, the bed, and assorted parts of the room.

Doc is not bashful in telling about his “minor deformity,” the one that kept him out of the Navy, but received no sympathy from the Army, which drafted him. He told this story during an interview:

The wind had blown the top off of our outhouse, and during that time, I had to go real bad. And I had this deformity. I could stand and pee over tall buildings. My brother Jim wouldn’t let me in, and I was about to bust, and I warned him and warned him. I don’t think but maybe one or two drops of that yellow liquid had come over the top when Jim busted out of that outhouse, and I forgot having to go. I had to run for my life.

Jim caught me—he was a great athlete and I was slow and clumsy—and he had me down ready to hit me. And then he said, “Well, I should have unlocked the door.” That was the kind of guy he was.

Another story is about Lawrence, a grinning, mischievous, happy-go-lucky, rotund kid of about seventy years who appeared to be the kind of fellow who could, and would, have fun at a funeral. Even when he became very ill, he never lost his sense of humor. He came into the office one day with an obviously bad cold.

“Lawrence,” I asked, “how did you ever manage to catch such a terrible cold?”

Lawrence grinned. “Well, Doc, I really don’t know for certain how I got it, but I think it might be because of these cool nights we’ve been a-havin’ here lately. You know how cold it’s been a-gettin’ every night these past few weeks, especially early in the mornin’. Well, at that time, I ain’t been sleepin’ under nothin’ but one thin woman.”

Then there was Mrs. Sosebee who had been diagnosed as suffering from obsessive-compulsive personality disorder with a fixation on extreme cleanliness. This obsession caused her to sometimes wash her hands more than two hundred times a day, and she often required treatment for a skin disorder brought on by the excessive handwashing.

On this particular visit to my office, Mrs. Sosebee’s massively swollen, red, and feverish right leg loomed as a problem. She had blood clots in that leg. But she refused hospitalization and told me, “No! I am not going to any hospital. You will have to find some way to treat me at home.”

“I will try to treat you at home,” I said, “but you must stay in bed; and I mean in the bed to the extent you have all your meals brought to the bed and use a pot at your bedside. Use the remote control for the TV or get someone else to change the channels for you.” She was to receive complete bed rest and to keep her leg elevated.

The following Tuesday when Mrs. Sosebee dutifully showed up in my office at the appointed time, it seemed perfectly obvious she had not been in bed. Her leg appeared more swollen than before and the redness and heat had increased. My unhappiness with the entire situation obviously showed. I began to tell her of my displeasure until Mrs. Sosebee gently patted my arm to interrupt me. She explained in the gentlest, softest, sweetest voice, “But, Doctor Skelton, surely you are smart enough to know that dirty laundry don’t take no doctor’s orders.” Her logic overwhelmed me. This lady considered cleanliness the most important thing in the world, even worth the risk of death. Her treatment continued at home, because she still gave me no other option. Mrs. Sosebee got well with no further problems and no permanent damage that we could recognize. What do we doctors know?

Then there was Miss Ocie, a teacher for more than fifty years, who fell at a PTA meeting one night and later complained of severe hip pain. X-rays showed a displaced fracture of the femoral neck in her left hip. An orthopedic surgeon from Athens, Georgia, was called in to perform surgery in the local hospital, where Miss Ocie could be closer to relatives and friends.

Following the surgery, Miss Ocie was not doing her prescribed exercises to build up her muscles. Weeks of no progress turned into a month. As we were about to begin the second month in which she had not taken one single step, it appeared obvious that some type of action must be taken now, and it was my duty to take it.

One Sunday morning, I walked into her room and made my stern statement: “Miss Ocie, the doctors and nurses have done what we can do for you. Your hip is nailed in exceptionally good position, and X-rays show healing is taking place. Two months have passed, and you have not taken one step. You do not seem to be working hard at the exercises we devised for you and are not gaining the strength we had expected.” My spiel continued: “I cannot walk for you. The nurses cannot walk for you. In fact, whether or not you ever take another step is strictly between you and The Man Upstairs.” Having said my piece, I whirled and left the room, not waiting for a reply. Miss Ocie turned to her sister, Miss Marie, and blustered, “I thought we were on the top floor.”

Doc Skelton has an amazing ability to make most anything rhyme. “Rhyming comes easily for me,” he said. So, when someone sent him a joke about Grandpa, Doc turned it into a poem:

When Grandpa Croaks

The door to the bedroom was slightly ajar

as Grandpa settled down for his nap.

Lately, it seemed he couldn’t go far

before he ran plumb out of zap.

Suddenly, wide open, the bedroom door bolted.

From his nap, poor Grandpa was jolted.

“Grandpa! Grandpa! Make a noise like a frog,”

came a voice, an excited grandson.

“Go away, Son,” Grandpa said in a fog,

“we’ll talk when my nap is done.”

The door hardly closed behind this one,

when it opened real fast like before.

This time, another eager grandson

said as he raced through the door,

“Grandpa! Grandpa! Make a noise like a frog!”

But Grandpa lay there like a log.

“Go away, Son! Can’t you see I’m trying to sleep?”

came the voice of an irate grandfather.

As the boy from the bedroom started to creep,

“That’s my boy! Now don’t be a bother.”

A third time, the door was flung open wide,

and in comes his favorite granddaughter.

Even Grandpa admitted he had too much pride

and loved her more than he ought to.

“Grandpa! Grandpa! Make a noise like a frog!”

Her sweet voice made Grandpa’s mind slip a cog.

“Make a noise like a frog? Why in this world?”

asked Grandpa, his mind in a whirl.

“Papa said,” came the answer from his favorite girl,

“when you croaked, we’d go to Disney World.”