Eighteen Thousand Long-Play Albums

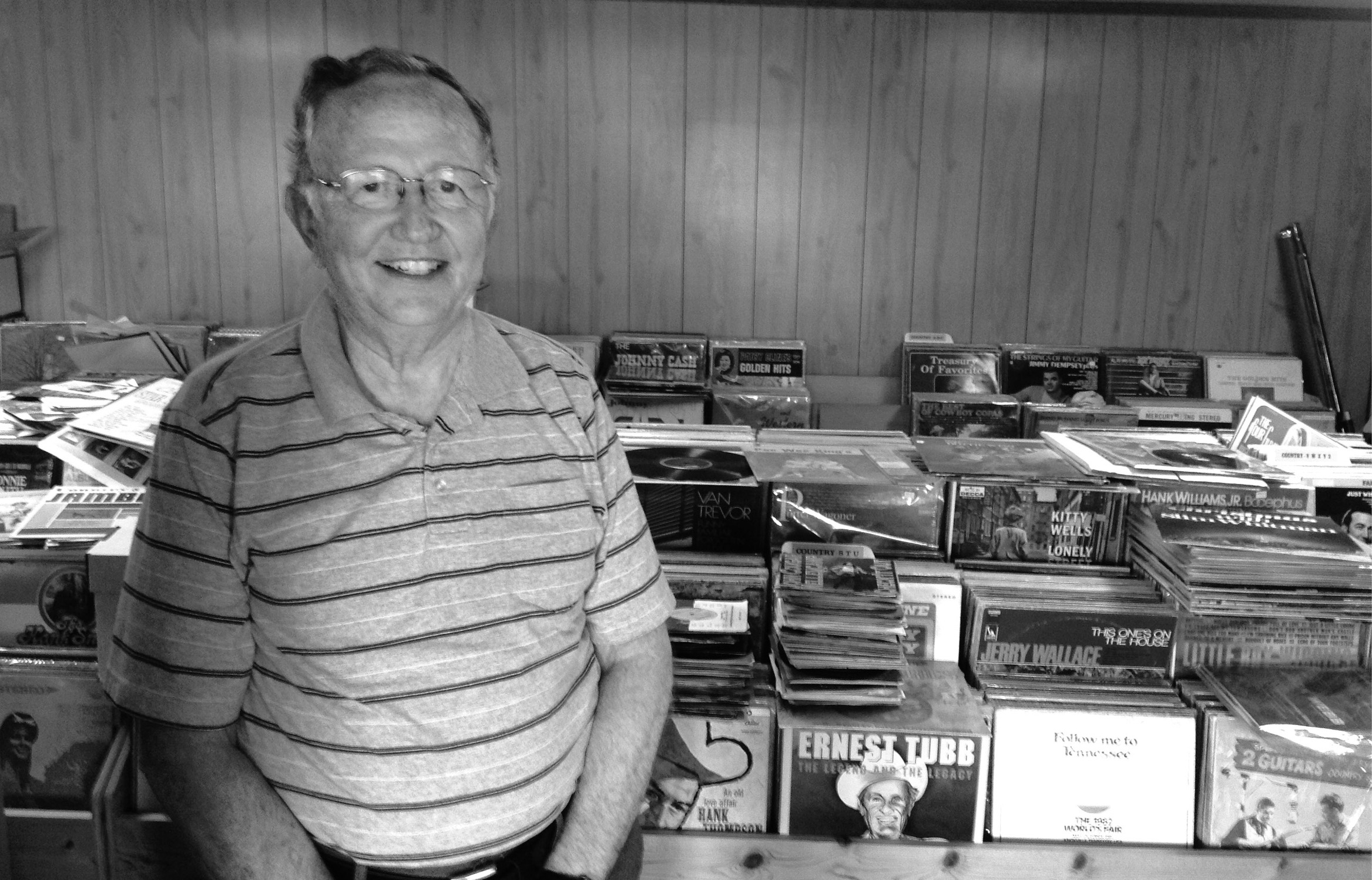

Jerry Kendall and his record collection

JERRY KENDALL SEEMED TO BE STALLING. I had asked to see the collection of LP albums in the basement of his home, a modest, mid-1970s house situated high on a hill overlooking Lake Chatuge near Young Harris, Georgia.

For any young people not familiar with the terms, LP stands for “long playing” or “long play”; an album is a phonograph record that contains a number of songs; a phonograph record is a vinyl, microgroove disc that is played on a machine that turns at thirty-three and a third revolutions per minute. And if it hadn’t been for technological advances in music presentation, your parents and/or grandparents might still be members of the Columbia Record of the Month Club, from which there seemed to be no escape short of the extinction of the product.

“Can we go down to the basement now?” I asked, again, eager to hear the story of a man obsessed with Southern gospel music, not to mention movie cowboys of yesteryear.

“Well, let me tell you about this right here,” Kendall said. He’d already gone through album after album ensconced in pasteboard boxes in his living room, naming singer after singer and musician after musician, many of whom he knew personally, had met at some point, or was related to. His mother had more than 125 first cousins.

“Here’s Billy Nicholson on steel guitar,” he said, holding an album. “He’s from here. Here’s Jimmy Hooper. He’s from here. Ken Fuller was a Methodist minister. He was here when he did this record. Now he’s retired here. Cranford Nix was from Blairsville, Georgia, and he played the banjo on a song by the Supremes in an album called The Supremes Sing Country, Western and Pop. Jerry Scoggins sang the Beverly Hillbillies theme song, and they made a movie in the nineties, and he sang it again. Tim Spencer was an original with the Sons of the Pioneers and wrote a bunch of songs. He published ‘How Great Thou Art.’ ”

PLATE 99 You can’t get eighteen thousand albums in one photo; here are a few of them.

Kendall pointed to a photo of singing cowboy Roy Rogers hanging on the wall, right beside a shot of Lake Chatuge before development and huge boat slips moved in. Roy Rogers was his favorite cowboy, a humble man who made a lot of money in movies and records, but who wasn’t obsessed with being wealthy, as cowboy Gene Autry was, Kendall said.

Finally, he consented. We could walk down to the basement.

“Just be ready for a shock,” he said, reaching the door. A shock because it’s not every day that one can see a collection of eighteen thousand LP albums in a three-compartment basement—yes, eighteen thousand albums: Southern gospel, cowboy, country, and other genres. Albums that fill every room, some in boxes, some in stacks, some on shelves.

And that number does not include seven thousand 45 rpm records and several hundred 78 rpm records. Kendall also has a collection of VHS and DVD movies, mostly Westerns.

How did his wife feel about his hobby? “Well, I’d already started when we got married,” Kendall said of his collection, failing to note that the collection has grown considerably since then.

Fortunately, Glynda Hayes Kendall, his wife of thirty-five-plus years, has a sense of humor. “I warned our neighbors a long time ago that if you see little black discs flying out over the lake, it’s not UFOs,” she said, laughing. “You can pretty much say, ‘Glynda’s had it.’ And he’s handed me one or two every now and then to flip out like a Frisbee.”

Is Glynda a fan of Southern gospel music? “Not to his extent,” she said, “but I enjoy it.”

The obvious question arises: Does this man of thousands of records sing? Alan, the older of the Kendalls’ two sons, answered that question a long time ago. “Alan was just a little thing,” Glynda Kendall said, “and we would be in the car, and Jerry would start singing with the tape or something. And it would be from Alan, ‘Daddy, please don’t sing.’ Finally, I asked him, ‘Why don’t you want Daddy to sing?’ ‘Because Daddy can’t sing.’ ”

Fortunately, the sons, Alan, thirty-five, and Kevin, thirty, can sing, very well. Alan has sung with three groups: the Melody Boys Quartet of Little Rock, Arkansas; Freedom of Sevierville, Tennessee; and the Rebels Quartet, a revamp of a quartet in Florida. He has also filled in for the Chuck Wagon Gang on several occasions.

Now that he’s the father of two, Alan has gone into a solo ministry, singing in churches, at fairs and festivals, concert settings, and “anybody that’ll have me,” he said.

Kevin sings at churches and with friends, but not professionally. But he did get to fill in a weekend for his brother as lead singer for the Rebels. Alan and Savannah were in Arizona adopting their daughter Evalee at the same time the Rebels were to sing in Florida, where Kevin lives. “I understand he did a really good job,” Alan said. So it’s clear that while Jerry Kendall has his albums, his sons have the voices.

Unable to find a place to sit down in the basement, we moved to the kitchen table upstairs to continue the conversation.

Jerry Bruce Kendall grew up in Towns County, Georgia, just down the road from where he lives now. All his relatives from his great-grandparents forward have lived in Towns County, “so I’m probably related to more than half the natives,” he said. He never knew his father, Homer Kendall, who was killed in World War II when his Navy ship was hit by a kamikaze plane. Jerry was only two months old.

Kendall’s love of Southern gospel music may be partly inherited. His mother, Velma Ree Nichols Kendall, was a fan, and after buying a record player, an RCA Victor machine, in 1950, she started her own small collection of records, mostly of Georgia-based groups: the Statesmen, the Harmoneers Quartet, Homeland Harmony, the LeFevre Trio, and the Sunshine Boys.

Kendall bought his first record when he was six years old. His grandfather had sold a calf and given him a dollar from the profit. “We were going to Gainesville, Georgia, to get shoes at Saul’s downtown,” he said, “and I bought my first record with that dollar.” It was a record by the Statesmen Quartet. On one side was “Listen to the Bells”; on the other, “I Want to Be Ready.” As you might expect, he still has that record.

He also kept his first record player, bought in 1958, when he was thirteen. It was that year that records began to pile up in the Kendall home.

Years later, when he had more money, Kendall occasionally would buy a whole box full of albums at a yard or garage sale, not knowing everything that was inside. “Sometimes you get some good ones,” he said.

But he’s not buying many records these days. He’s even sold a few, mainly at the Grand Ole Gospel Reunion in Greenville, South Carolina. But when you’ve packed more than twenty-five thousand records into your home, it’s hard to tell when a few are missing. Kendall pretty much stopped visiting record stores years ago, back when there were such things as record stores, because he had more music than they did.

He’s been retired for several years after thirty-three years at Towns County Family and Children Services, twenty-seven as its director. He now has time to scavenge for more records, but where would he put them?

“I’m a little embarrassed about it now,” he said. “What in the world was I thinking about, getting all those records? A lot of them are worth a lot of money. It’s hard to know what to do. I want to sell some. My sons are into music, but they won’t want all those records.”

As it is with other collectors, it’s not about the money or the bragging rights. It’s about sentimentality and memories.

PLATE 100 A shot of Kendall’s first record

Kendall can pull out a 1952 album by the Blackwood Brothers, one of his more collectible pieces, and remember just how much he enjoyed that group a few decades ago.

But he seldom plays any of his records, not because he can’t find the one he wants—his basement collection is categorized and filed mostly alphabetically—it’s just that he’d rather sit back and hear one of his sons sing, maybe at his church, Woods Grove Baptist Church. Music, after all, and certainly Southern gospel music, is best when it’s enjoyed as a family. And that’s when Jerry Kendall seems most proud: when he talks about his family.

He knows that a collection of records can be worth some money, but a collection of family memories is priceless.