Snaking Logs Through the Kentucky Woods

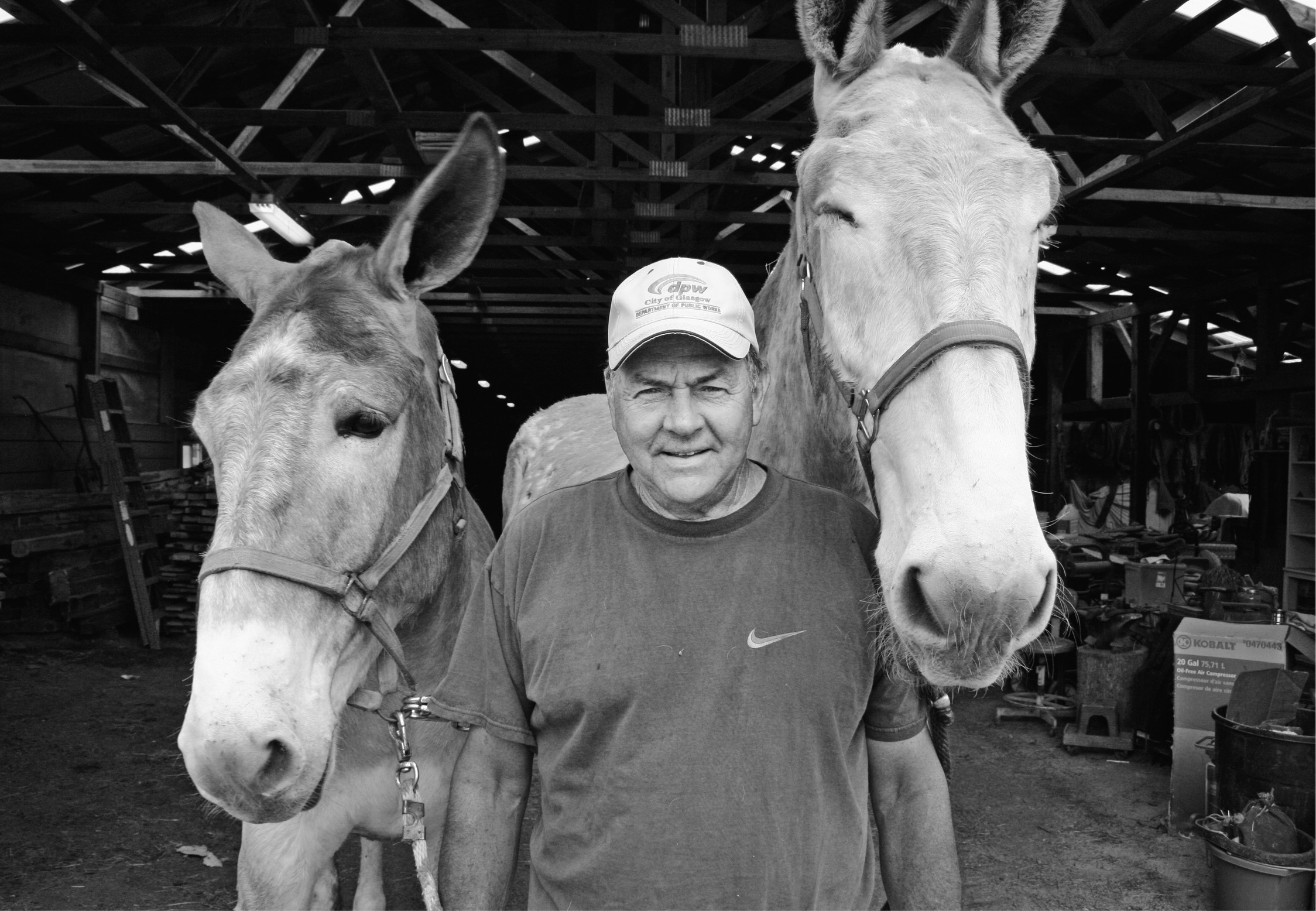

Hollis Thrasher and his mules

WHEN HOLLIS THRASHER was five years old, his father would harness two mules and hand the lead reins for one to Hollis and the reins for the other to Hollis’s brother, Curtis, who was six. The boys’ job was to lead those stubborn animals about a mile through the woods to their grandfather’s place, while their daddy drove a truck on the road to meet them.

A few years later, Hollis and Curtis were riding, not leading, the mules to Granddad’s, and sometimes even farther away. And then, a few years after that, they were plowing with a mule, just like the grown-ups. “We worked those old mules every year, summer and winter,” Hollis remembers.

That’s because their daddy, trying to eke out a living for his growing family, would rent every old tobacco patch he heard about, even if it was just a half-acre ten miles away. That meant Hollis and Curtis, as soon as they were big enough, were riding mules bareback for ten miles, plowing and working most of the day, and then riding ten miles back home. At night, the insides of their legs were so galled, they could barely walk.

One day, Curtis, in a fit of mule-induced exasperation, said, “Hollis, when I’m grown and I get gone, I’m never going to look one of these in the butt again.”

But it didn’t happen that way with Hollis. “When I got out of the service and out of college,” he says, “the first thing I wanted to buy myself was a pair of mules. Now, that was before a home or a car or anything. I wanted a good pair of mules.” He stresses a good pair because the mules his daddy owned are what Hollis calls junk. “He’d have a red one with a black one or a white one with a black one. He’d have a little one and a big one.”

PLATE 103 Hollis and his mules

But Hollis Thrasher doesn’t buy junk, at least not intentionally. Most of his mules stand head and shoulders above the others. He owns two blond ones, Sam and Bert, whose mamas were Belgian mares. The Belgian Heavy Draft horse can reach seventeen hands or sixty-eight inches tall, but Sam is already slightly more than eighteen hands tall. And he’s not fully grown.

When his mule-buying fever first began raging, Thrasher found himself the proud owner of ten mules, but his wife, Carolyn, suggested he pare down his herd. “He sold two and bought three,” she says, “and I told him he needed to work on his math.” At the time of this writing, Thrasher was down to only six mules.

Elvin Hollis Thrasher was born at home on August 29, 1948, the second of seven children of Kendle and Arvella Thrasher. After living a year and a half in a chicken-coop-type house behind his parents’ home, Kendle bought a 130-acre farm in Clinton County, Kentucky. A creek with the unlikely name of Ill Will ran behind the house and flowed into Dale Hollow Lake about a quarter mile away. Hollis remembers chasing minnows up and down Ill Will Creek when he was just big enough to walk.

He also remembers his daddy’s unpredictable, unmatched mules. For whatever reason, when it was time to lead them, brother Curtis always got the one that was difficult. The boys and their mules had to conquer a steep hill on the way to their grandfather’s farm, and the mules would get tired.

“I remember that old mule of my brother’s would just stop,” Thrasher says, smiling. “He couldn’t get him to go. You could figure on about five minutes when he was just going to stand there, and then he’d go on. Curtis would get so mad. My brother looked that mule in the eye one day and said, ‘When I get big, I’m gonna whip you.’ And him six years old at the time.”

“Dad would remind us, ‘Boys, never trust a mule a hundred percent. He’ll work for you for forty years to get a chance to kill you.’ ” Hollis learned the truth of that warning when he was five or six years old.

Egged on by Curtis, one day he stuck his head through a hole in the barn and continuously poked a mule with one of his mother’s bean sticks. The agitated animal ran by, kicked, and plastered the boy right in the head. Hollis was out cold. “Mama said it was a good thing the mule didn’t have his shoe on,” Hollis says, “because it probably would have killed me.”

Thrasher recalls his parents as good, hardworking people. “Mom is a good example of hard work won’t hurt you,” he says, “because I never knew anybody that worked harder than my mom did. She was the last one to go to bed after working out in the fields with us.”

Kendle Thrasher occasionally would travel to Louisville, Kentucky, to find seasonal work while his wife stayed behind to put out the crops, cook meals, and look after the children.

Arvella was a good mother, Thrasher says, but her way of tending to the baby—and with seven children, there was always a baby—would not get the seal of approval today from children’s services. She would leave it in a baby pen on the back porch and go to work chopping tobacco. But she always stayed within earshot. Today, “they would have you down in the courthouse for negligence,” Thrasher says.

A good mule, a well-trained mule, Thrasher says, is one “that’ll listen to you, one that’s not always wanting to run off from you. He’s the kind that you can take him to the woods and lay your lines down, pick up your saw, cut a tree down, and he’s still standing there. You need one that you can ‘whoa’ at him to stop and he’ll stop.”

PLATE 104 Sign says it all.

Still, even with a good mule, it pays to use caution when approaching the animal from his blind side. Thrasher didn’t do that one day—he forgot to “whoa” the critter or let him know he was coming. “And just as I laid my hand on his side, he kicked me in the fat part of my leg and kicked me about ten feet backwards on the ground.” Fortunately, the leg was not broken, only bruised and sore for a few days. “You know,” he says, “I never did forgive that mule for that. I kept him on for two years, but I never did forgive him. I ended up selling him.”

But Hollis Thrasher was not deterred. He still relies on each of his mules to be, well, maybe not his best friend, but at least a companion he can depend on when he’s needed. In fact, he thinks a mule may be smarter than a horse. He says he’s seen a mule in danger, such as getting a leg hung in a fence, but not stupid enough to keep pulling and squirming if he’s being hurt. “A horse will tear a leg off before they quit,” he says.

And a mule can learn commands if he hears them repeatedly. “Gee” and “haw” are examples, the words used to get a mule to turn right or left. “Pulling a log is the best way to teach that,” Thrasher says.

It’s hard to say what a mule driver is supposed to look like, but if being physically fit is part of the description, then Hollis Thrasher, now in his late sixties, looks like a mule driver. He also has the commanding voice of a drill sergeant—he was trained as one in the Army—so no mule can claim he didn’t hear his instructions.

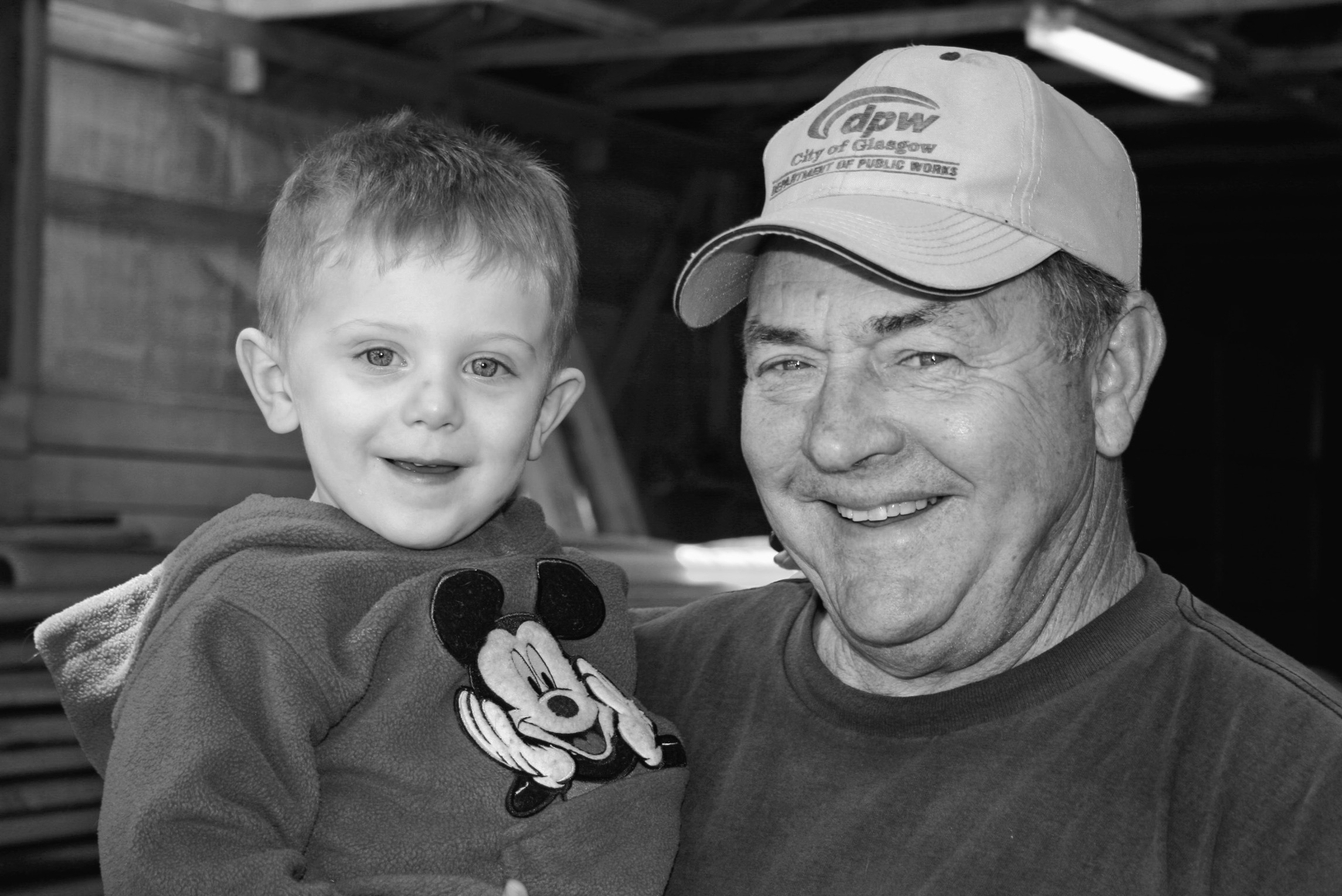

Tough as he is, though, Thrasher obviously is a real softie when it comes to children. He likes to tell about the hayride he ran in his community about fifteen years ago. Thrasher and his mules had been hauling kids for some time when a little girl, maybe five years old, brought him a hamburger and Coke.

Just for that, he told the girl, you can ride as many rides as you want, free of charge. “Now that girl is grown and going to vet school,” he says. “But she still remembers that.”

Thrasher has competed in a lot of contests and won. In 2002, he entered the wagon class in Columbia, Tennessee’s Mule Day, an annual celebration that began in 1840 as “Breeder’s Day,” a meeting for mule breeders, and now draws more than two hundred thousand people for a four-day event. He was driving a covered wagon.

“The others could see better,” he recalls, “because they sat up high and didn’t have a cover to look around.” He was the last of eleven competitors to run an obstacle course. Seven of the eleven had been disqualified because their wagons touched one of the obstacles. Three drivers and their mules had performed perfectly.

“I ran those mules,” Thrasher says. “I had to look out the side windows on the covered wagon.” He won. And when it was over, the contest judge said, “We’ve never seen one that fast in this contest.”

He also won the individual-mule class that year, pulling a sled through an obstacle course. Unlike most competitors, he used no lines, guiding the mule solely by voice commands.

But with all his skills, Thrasher doesn’t claim to be the greatest mule handler in his circle of friends. For that honor, he names Billy Coomer of Edmonton, Kentucky, who estimates he’s won a hundred or more mule contests. So what’s the secret to being a good mule man? “I don’t know, buddy,” Coomer says. “Probably have to be smarter than the mule. You just got to know your animal.”

PLATE 105 Hollis and grandson John Paul Dubarry III

Animals are a lot like children, Coomer says. When a kid gets up about fifteen years old, and he doesn’t want to work, it’s hard to get him to do anything. “And that’s just about the way a mule or a horse is. If you don’t break him when he’s young, a lot of time he won’t have a lot of sense. You got to study your animal when you’re working it. And if it wants to goof up, you can tell it if you watch him before he goofs up.”

A mule has his own personality, Coomer says, and there are some good ones and some that are of no-account. “I’ve had a lot of sorry mules,” he says.

Working with mules, however, “is sort of leaving out of here,” according to Coomer. “Used to go to a mule sale and there’d be a thousand head of mules down there. That was twenty years ago. Now you go down there and they’ll be two or three hundred.”

Thrasher calls Coomer the best driver he’s ever seen. “When I say he’s good, I mean he’s got good hands. When you drive a team, you’ve got to have good hands. You’ve got to know how much pressure you need to put in a mule’s mouth to get him to respond to you.” So when Coomer wants to help Thrasher snake a few logs, he’s certainly welcome.

Thrasher’s wife is often there on the job, too, not to do any snaking, but to make sure her husband doesn’t get hurt out there in woods all alone. It’s dangerous work, Carolyn Thrasher says, but “it’s a good, slow-down kind of life.”

But Hollis Thrasher doesn’t say anything about slowing down. He doesn’t want to work every day, of course, but it’s not unusual in the wintertime to see him out in the woods three days a week geeing and hawing a mule or two, or maybe even four, if he’s using a two-wheel log cart.

“You know,” he says, “it’s kind of nice to do what you enjoy doing and make money at the same time.”

To Hollis Thrasher, there’s nothing like training a mule to do what he’s supposed to do, and then watching him do it. His wife supports him, but may not get the same enjoyment.

“I think the day I die,” he says, “she’ll call somebody to bring their horse trailer and come get these mules.”