Figure 2.1 The Tree of Knowledge

This chapter will cover:

“A mind map harnesses the full range of cortical skills—word, image, number, logic, rhythm, color, and spatial awareness—in a single, uniquely powerful technique. In doing so, it gives you the freedom to roam the infinite expanse of your brain.”

This definition comes from Tony Buzan who is the originator of mind maps and a best-selling author. Tony developed mind mapping in the late 1960s, and it is now estimated that millions of people all over the world create them in order to use their minds more effectively.

Idea mapping has a rich foundation in mind mapping and I am grateful to Tony for giving this to the world. Here is the difference. After 15 years of real-world experience and seeing business people around the world apply this technique to their careers and lives, it was time for the next generation—a hybrid of sorts. Idea mapping is the tool that helps many who struggle with keeping with the laws of mind mapping and who often (sadly) throw out the baby with the bath water. The laws are important to understanding so that you know when it is applicable to use them and when it is not. Thus my front-line experience with skeptical, overworked linearly trained business people has caused me to craft idea maps as the practical, flexible, and more usable version of mind maps. Once the rules and techniques of idea mapping are established and learned, you’ll be breaking everyone of them to make these graphical works apply to you in the most effective way possible. You will be the creator of your own rules that work for you!

Now let’s look back at the history even further.

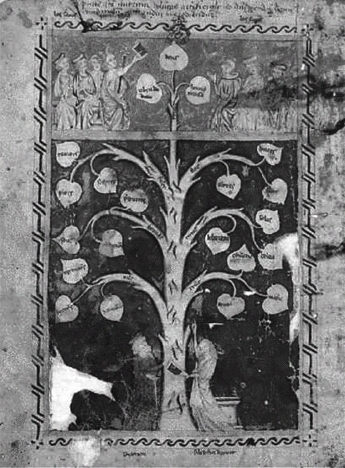

I thought it would be fascinating for you to see some historical examples of early graphical organizers. Since the term mind mapping was not around at that time, they were referred to as tree diagrams.

In one of Ramon Llull’s diagrams called the “Tree of Knowledge” (about 1270 AD) the core concept or trunk is clearly the central theme. (You will come to know this as a central image when creating your idea maps.) This theme is fully surrounded by subordinate concepts. (You will come to know these as main branches.) See Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 The Tree of Knowledge

A second example of Ramon Llull’s drawings also shows knowledge arranged in a tree diagram. It is called “Arbre de filosofia d’amor” (“The Tree of the Philosophy of Love”; 1298 AD). See Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2 The Tree of the Philosophy of Love

The graphical display of knowledge or ideas using color, lines, and association to assist human thinking was well known by medieval times. Although mapping may be a new concept to you, I think it is exciting to breathe new life into systems that have been proven over time. For this source and more historical information on graphical languages, go to www.futureknowledge.biz. Scroll down on the home page and click on “frequently asked questions.” In the answer to question number one you will find Michael Cahill’s (President of Future Knowledge Group, Inc.) white paper on the History and Uses of Graphical Languages.

I spent the years from 1985 to 1997 working in various leadership roles for an information technology company. In my last position, where I was introduced to mind mapping, I was a management training specialist in a leadership development organization. It was an organization of top leaders assigned to teach leaders about leadership.

I first learned how to map in 1991 from a coworker. I received my formal certification in mind mapping in 1992 from Vanda North, who was previously the founder and global director of the Buzan Centres and is now the founder and director of The Learning Consortium based out of the UK. She was and continues to be a great friend and mentor. I spent the next 5 years teaching 2-day Mind Matters workshops throughout the United States and Canada for this employer. For many this workshop was the most impactful learning experience of their lives.

Between July 1, 1992, and June 30, 1993, 1,397 U.S. participants attended this course. A survey was sent randomly to 350 of those students with a return rate of 37%. The results were detailed, extensive, and extremely positive. It showed that 85% of the respondents applied tools from this workshop to their business/personal lives. The survey results documented a phenomenal transfer of skill from the class to the real world compared to all of the other corporate offerings. The following year the statistics were equally positive. One of the most profound results stated that 73% of the respondents said that the workshop had made a lasting impact on their business/personal lives. This was followed by three pages of quotes describing the specifics of the workshop’s impact.

I witnessed many situations where the use of this tool helped leaders become incredibly successful as a result of their willingness to learn and apply this skill. My passion for this work and the exhilaration of the results continued to grow. In early 1997 this workshop and all other vendor-related courses were cut in a downsizing effort. I was at a crossroad: Do I stay with this company and do something I wouldn’t enjoy? Or, do I leave, start my own company, and follow my passion to teach these skills to others? I left. It was an easy choice, and I’ve never looked back.

Today I combine my corporate leadership experience, my facilitation and training skills, and this wonderful tool of idea mapping to teach people all over the world.

Let’s find out how you currently organize your thoughts by imagining a situation that you have probably already experienced in some fashion. Assume you’ve been asked to give a presentation to a group of people and you only have 5 minutes to gather your thoughts about a particular topic. This could be the status of a project you are working on, sharing your experience in an area of expertise, updating your team on a meeting you attended, standing in for an absent presenter, or any other topic of your choice. Typically you have been given a general idea of the topic. Your assignment is to take a few minutes to choose a topic for a 30-minute presentation, create the notes that you would take to the podium, and organize them in the format and in the way you would normally do so. Take 5 minutes to create notes for this particular task before moving on. Once you have completed your notes, proceed to the next section.

Looking at these notes, again answer the questions from Chapter 1 where we reviewed your baseline notes. In addition, answer the following questions:

A key issue to focus on within this exercise is your method of thought organization. In my experience, the majority of people use a chronological approach to generate ideas that will eventually be presented in a sequence. They focus all their effort on what to say first—not writing anything down until they get past that hurdle. Even when the outcome doesn’t require a sequential outcome we respond similarly. When the purpose is to come up with the most creative solution or idea, most people will try to think of the best idea to the exclusion of any other options. This is normal linear thinking and creates barriers to our creativity and thought processes.

Let’s examine this more closely by referring again to the 30-minute presentation notes created for the activity in this chapter. While your brain was focusing on what to say first, did you notice any other ideas popping into your brain? Probably. When these other creative ideas came to mind what did you do? What usually happens is these out of sequence thoughts don’t get captured because people feel compelled to start at the beginning and work their way through to the end in a linear process. This is similar to the trap people can fall into when reading a book. Many feel they must read from page one and go all the way to the end—even if they find they don’t like the book shortly after starting—even if data is only needed from a few chapters. (In this book, please give yourself permission to read in any order and in any quantity that is best for your purpose.)

By the time you reach the point in your notes where the other ideas (the ones you had before you were ready to have them) would have been beneficial, they’re gone—forgotten! These ideas could have shaped the initial part of your presentation and made creating what you would say first much easier. Instead we spent more time getting inferior results. This is one of the problems with using a chronological or linear approach.

Let’s look at two ways the brain creates associations. The first method is called a bloom of associations (BrainBloom™ process developed by Vanda North). This is a process in which all ideas are generated from and associated to a central thought. All associations radiate from a central idea. The second method is called a flow of associations. In this case, the association begins with a single thought that leads to another thought, which leads to another thought. It’s like a long stream of consciouness.

The creation of an idea map combines the bloom and flow of associations. Following are three activities that will demonstrate the bloom, the flow, and the bloom plus flow of associations.

Idea mapping uses the logic of association in creating its structure. It also combines this with chronology, but that comes after the ideas have been generated. Let’s do an activity that will better demonstrate what is meant by the logic of association.

Take a sheet of blank paper and write a word in the center of the page. You can use any single word or use my example in Figure 2.3. Off of this word, draw 10 blank lines.

Figure 2.3 Bloom of Ideas

On the lines, write the first 10 single words that come to mind when you think of the word in the middle. This process represents a bloom of thought. These 10 words associate to the central word.

Next we’ll do something a bit different. Again start with a single word of your choosing or use mine in Figure 2.4. Draw a line from your word, another branch from that one, and so forth, until you have 10.

Figure 2.4 Flow of Ideas

Beginning with the first line off of computer, write the first word that comes to mind when you think of the word computer. On the next line write the first word that comes to mind when you think of the word you just wrote down. Follow this pattern until you’ve completed 10 words. This represents a flow of thought. Each word associates to the previous word.

So far we’ve differentiated between blooming and flowing. Here’s the next critical lesson. It applies to capturing ideas as your brain creates thoughts.

Let’s look at the two activities just completed. In the bloom example, I imagine it was hard to stay completely focused on the central word as your primary source of association. It’s natural to start a flow of associations at times because the brain just can’t help it! It is associative in its design. In the flow example, there were probably several choices of associations each time you wrote down a word. In this case our brains were blooming at each point, and we simply selected the word that stood out the most for whatever reason.

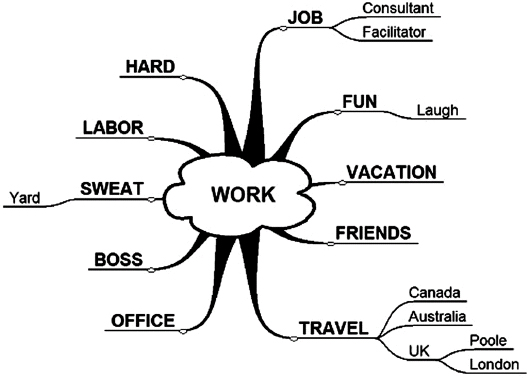

So let’s do one last activity that combines both the bloom and the flow of associations. Go back to your bloom activity. In my example I used the word WORK. I made 10 associations as you can see in Figure 2.5. Even if we used the same central word, I doubt we had many associations in common because our experiences and associations with this word are different.

Figure 2.5 Bloom + Flow of Ideas

This time add single-word associations to your original bloom activity. Look at the central word plus the 10 surrounding words. When the first word associating to any of these 11 words (including the word WORK) comes to mind, draw a line connecting to the associating word and write your new word on that line. See the following example using the word WORK as the central thought. Words will come to you randomly. Go where your mind takes you. Let the ideas come naturally. You will be blooming and flowing at the same time—a natural reflection of how the brain works! Spend 3 or 4 minutes allowing this process to work. If you have a question about where a word should go, ask yourself, “To what branch does my new word connect?” That’s where you draw a new line and then write the word on that line.

Let me explain what I did in Figure 2.5. When I did my initial bloom around the word WORK, the words I thought of were job, fun, vacation, friends, travel, office, boss, sweat, labor, and hard. I don’t know why those were the first 10 words that came to mind—they just were. However, I do know what each word represents. I thought of job because it’s a synonym for work. Fun came to mind because my work is extremely fun. I also need rest from work, so that made me think of vacation. I have great friends with whom I work. My office is a mess. Physical work makes me sweat. Work could also be called labor, and sometimes work is hard.

Next I asked you to make additions to your original bloom of ideas. I added more words (in no particular order) to further define the existing words. I added consultant and facilitator to describe portions of my job, laugh to expand on what I consider to be part of fun, a few of the locations where I travel, and finally I sweat when working in the yard. It’s very important to understand that I broke this process into two phases to teach you the difference between blooming and flowing. If I had been creating an idea map, I would not complete the bloom before allowing myself to add sub-ideas. I would add ideas as I thought of them—regardless of where they would be positioned in the map.

Soon you will be using this technique to create and deliver presentations, keep track of what needs to be done, plan meetings, develop marketing strategies, dissect a complex problem, and do many, many more applications.

You have experienced how the brain generates ideas associatively in the bloom and flow activities. The best strategy for capturing ideas comes back to Lesson Two—“Where your brain goes, you will follow.” This lesson applies even when generating thoughts for an application that will require chronology in the final draft. An idea map will provide the structure in which you can organize and sequence ideas despite their random creation. Generating ideas for a task where the eventual outcome will require chronology brings us to another lesson:

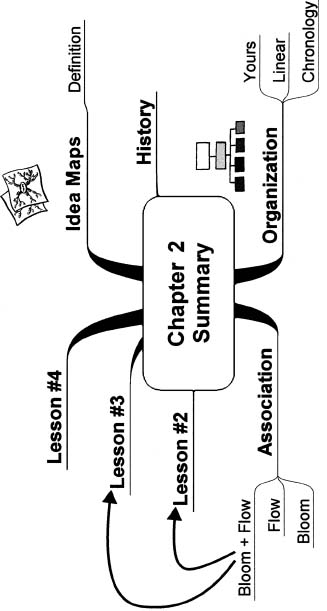

The associative process is the logic by which an idea map is created. It is a natural reflection of how the brain works. See Figure 2.6 for my summary of this chapter in an idea map. You’re now ready to look at the laws of idea mapping, learn how to read an idea map, and start creating one of your own.

Figure 2.6 Chapter 2 Summary