Chapter 3. (Basics of Racket)

You’ve written your first program. It consisted of a few functions that dealt with numbers. You’ve seen the basics of expressions and definitions. You know there are a lot of parentheses.

Now it’s time to bring some order to chaos. In this chapter, we’ll show you other kinds of data, as well as the general structure and meaning of Racket programs.

|#

3.1 Syntax and Semantics

To understand any language—be it a human language or a language for programming—requires two concepts from the field of linguistics. Computer scientists refer to them as “syntax” and “semantics.” You should know that these are just fancy words for “grammar” and “meaning.”

Here is a typical sentence in the English language:

My dog ate my homework.

This sentence uses correct English syntax. Syntax is the collection of rules that a phrase must follow to qualify as a valid sentence. Here are some of the rules of sentences in the English language that this text obeys: the sentence ends in a punctuation mark, contains a subject and a verb, and is made up of letters in the English alphabet.

However, there is more to a sentence than just its syntax. We also care about what the sentence actually means. For instance, here are three sentences that, roughly, have the same semantics:

The first two are just different ways of saying the same thing in English. The third sentence is in Chinese, but it still has the same meaning as the first two.

The same distinction between syntax and semantics exists in programming languages. For instance, here is a valid line of code written in C++:

((foo<bar>)*(g++)).baz(!&qux::zip->ding());

This line of code obeys the rules of C++ syntax. To make the point, we put in a lot of syntax that is unique to C++. If you were to place this line of code in a Python program, it would cause a syntax error.

Of course, if we were to put this line of code in a C++ program in the proper context, it would cause the computer to do something. The actions that a computer performs in response to a program make up its semantics. It is usually possible to express the same semantics with distinct programs written in different programming languages; that is, the programs will perform the same actions independent of the chosen language.

Most programming languages have similar semantic powers. In fact, this is something that Al and his student Alan Turing first discovered in the 1930s. On the other hand, syntax differs among languages. Racket has a very simple syntax compared to other programming languages. Having a simple syntax is a defining feature of the Lisp family of languages, including Racket.

3.2 The Building Blocks of Racket Syntax

From the crazy line of C++ code in the previous section, you can get the hint that C++ has a lot of weird syntax—for indicating namespaces, dereferencing pointers, performing casts, referencing member functions, performing Boolean operations, and so on.

If you were to write a C++ compiler, you would need to do a lot of hard work so that the compiler could read this code and check the many C++ syntax rules.

Writing a Racket compiler or interpreter is much easier as far as syntax is concerned. The part of a Racket compiler that reads in the code, which Racketeers call the reader, is simpler than the equivalent part for a C++ compiler or the compiler for any other major programming language. Take a random piece of Racket code:

(define (square n) (* n n))

This function definition, which creates a function that squares a number, consists of nothing more than parentheses and “words.” In fact, you can view it as just a bunch of nested lists.

So keep in mind that Racket has only one way of organizing bits of code: parentheses. The organization of a program is made completely clear only from the parentheses it uses. And that’s all.

In addition to parentheses, Racket programmers also use square brackets [] and curly brackets {}. To keep things simple, we refer to all of these as “parentheses.” As long as you match each kind of closing parenthesis to its kind of opening parenthesis, Racket will read the code. And as you may have noticed already, DrRacket is extremely helpful with matching parentheses.

The interchangeability of parentheses comes in handy for making portions of your code stand out for readers. For example, brackets are often used to group conditionals, while function applications always use parentheses. In fact, Racketeers have a number of conventions for where and when to use the various kinds of parentheses. Just read our code carefully, and you’ll infer these conventions on your own. And if you prefer different conventions, go ahead, adopt them, be happy. But do stay consistent.

Note

Code alone doesn’t make readers happy, and therefore Racketeers write comments. Racket has three kinds of comments. The first one is called a line comment. Wherever Racket sees a semicolon (;), it considers the rest of the line a comment, which is useful for people and utterly meaningless for the machine. For emphasis, Racketeers use two semicolons when they start a line comment at the beginning of a line. The second kind of comment is a block comment. These comments are useful for large blocks of commentary, say at the beginning of the file. They start with #| and end with |#. While you may recognize the first two kinds of comments from other languages, the third kind is special to Racket and other parenthetical languages. An S-expression comment starts with #; and it tells Racket to ignore the next parenthesized expression. In other words, with two keystrokes you can temporarily delete or enable a large, possibly nested piece of code. Did we mention that parentheses are great?

|#

3.3 The Building Blocks of Racket Semantics

Meaning matters most. In English, nouns and verbs are the basic building blocks of meaning. A noun such as “dog” evokes a certain image in our mind, and a verb such as “ate” connects our image to another in a moving sequence.

In Racket, pieces of data are the basic building blocks of meaning. We know what 5 means and we know that 'hello is a symbol that represents a certain English word. What other sorts of data are there in Racket? There are many, including symbols, numbers, strings, and lists. Here, we’ll show you the basic building blocks, or data types, that you’ll use in Racket.

Booleans

Booleans are one of Racket’s simple data forms. They represent answers to yes/no questions. So when we ask if a number is zero using the zero? function, we will see Boolean results:

> (zero? 1) #f > (zero? (sub1 1)) #t

When we ask if 1 is zero, the answer is #f, meaning false or no. If we subtract 1 from 1 and ask if that value is zero, we get #t, meaning true or yes.

Symbols

Symbols are another common type of data in Racket. A symbol in Racket is a stand-alone word preceded by a single quote or “tick” mark ('). Racket symbols are typically made up of letters, numbers, and characters such as + - / * = < > ? ! _ ^. Some examples of valid Racket symbols are 'foo, 'ice9, 'my-killer-app27, and even '--<<==>>--.

Symbols in Racket are case sensitive, but most Racketeers use uppercase sparingly. To illustrate this case sensitivity, we can use a function called symbol=? to determine if two symbols are identical:

> (symbol=? 'foo 'FoO) #f

As you can see, the result is #f, which tells us that Racket considers these two symbols to be different.

Numbers

Racket supports both floating-point numbers and integers. As a matter of fact, it also has rationals, complex numbers, and a lot more. When you write a number, the presence of a decimal point determines whether your number is seen as a floating-point number or an integer. Thus, the exact number 1 and the floating-point number 1.0 are two different entities in Racket.

Racket can perform some amazing feats with numbers, especially when compared to most other languages. For instance, here we’re using the function expt to calculate the 53rd power of 53:

> (expt 53 53) 243568481650227121324776065201047255185334531286856408445051308795767 20609150223301256150373

Isn’t that cool? Most languages would choke on such a large integer.

You have also seen complex numbers. Consider this example:

> (sqrt -1) 0+1i > (* (sqrt -1) (sqrt -1)) -1

Racket returns the imaginary number 0+1i for (sqrt -1), and when it multiplies this imaginary number by itself, it produces an exact -1.

Finally, something rational happens when you divide two integers:

> (/ 4 6) 2/3

The / function is dividing four by six. Mathematically speaking, this is just two over three. But chances are that if you’ve programmed in another language, you would expect this to produce a number like 0.66666...7. Of course, that’s just an approximation of the real answer, which is the rational number two over three. Numbers in Racket behave more like numbers that you are used to from math class and less like the junk other languages try to pass off as numbers. So Racket returns a rational number, which is written as two integers with a division symbol between them. It is the mathematically ideal way to encode a fraction, and that is often what you want, too.

You will get a different answer if your calculation involves an inexact number:

> (/ 4.0 6) 0.6666666666666666

Compared with the previous example, this one uses 4.0 in place of 4. You might think 4.0 and 4 are the same number, but in Racket, the decimal notation indicates an inexact number; 4.0 really means some number that is close to four. Consequently, when you divide a number that is close to four by six, you’ll get back a number that is close to ⅔, namely 0.6666666666666666.

Inexact numbers, like 4.0, are called floating-point numbers, and basically they don’t behave like any kind of number you’ve seen in a math class. But the important thing to remember is that if you never use decimal notation, you won’t need to worry about how these kinds of numbers behave. Exact numbers in Racket are honest numbers like the ones you learned about in grade school.

Strings

Another basic building block is the string. Although strings aren’t really that fundamental to Racket, any program that communicates with a human may need strings, because humans like to communicate with text. This book uses strings because you are probably used to them.

A string is written as a sequence of characters surrounded with double quotes. For example, "tutti frutti" is a string. When you ask DrRacket to evaluate a string, the result is just that string itself, as with any plain value:

> "tutti frutti" "tutti frutti"

Like numbers, strings also come with operations. For example, you can add two strings together using the string-append function:

> (string-append "tutti" "frutti") "tuttifrutti"

The string-append function, like the + function, is generalized to take an arbitrary number of arguments:

> (string-append "tutti" " " "frutti") "tutti frutti"

There are other string operations like substring, string-ref, string=?, and more, all of which you can read about in Help Desk.

3.4 Lists in Racket

Lists are a crucial form of data in Racket. Racket data is like a big toolbox, and you can make amazing things if you know how to utilize your tools. You can’t do anything without a trusty hammer, an ever-helpful screwdriver, and some needle-nose pliers. These basics are symbols, numbers, and strings in Racket. Then you have all the power tools— chain saws, drills, planers, and routers—that take everything to the next level, just like Racket lists and structures. Well, you really can’t make anything in Racket without the basic cons cell, which is actually one of the most powerful tools Racket offers.

CONS Cells

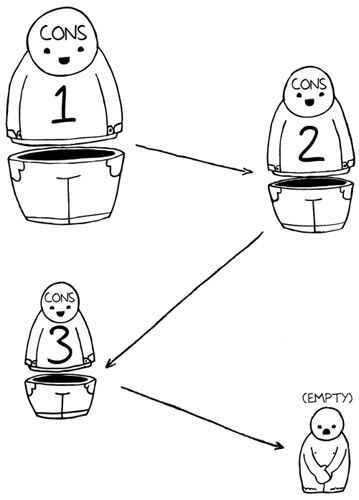

Lists in Racket are held together with cons cells. Understanding the relationship between cons cells and lists will give you a better idea of how complex data in Racket works.

A cons cell is made of two little connected boxes, each of which can point to any other piece of data, such as a string or a number. Indeed, a cons cell can even point to another cons cell. By being able to point to different things, it’s possible to link cons cells together into all kinds of data, including lists. In fact, lists in Racket are just an illusion—all of them are actually composed of cons cells.

For instance, suppose we create (list 1 2 3). It’s created using three cons cells. Each cell points to a number, as well as the next cons cell for the list. The final cons cell then points to empty to terminate the list, such as (cons 1 (cons 2 (cons 3 empty))). If you’ve ever used a linked list in another programming language, this is the same basic idea. You can think of this arrangement as similar to a calling chain for your friends. “When I know about a party this weekend, I’ll call Bob, and then Bob will call Lisa, who will call . . .” Each person in a calling chain is responsible for only one phone call, which activates the next call in the list. In the Realm of Racket, we also like to think of them as nesting dolls that shed layers until the last doll, which is rock solid.

Functions for CONS Cells

In this day and age, it is rare for a Racket programmer to manipulate cons cells as dotted pairs. Most of the time, these cells are used to build lists and nested lists, and there are great functions for dealing with all kinds of lists.

On some rare occasions, you may want to play with plain cons cells. So here is how you create a raw cons cell:

> (cons 1 2) '(1 . 2)

As you can see, the result is a list with a dot. You can give a cons cell a name with define:

> (define cell (cons 'a 'b))

And you can extract the pieces of data that you stuck into a cons cell:

> (car cell) 'a > (cdr cell) 'b

That is, if x is the name for a cons cell, car extracts the left piece of data from x and cdr extracts the right one.

Now you may wonder how anyone can be so crazy as to come up with names like car and cdr. We do, too. Therefore we focus on cons cells as the building blocks of lists and move on.

Lists and List Functions

Manipulating lists, not nested cons cells, is important in Racket programming. There are three basic functions for manipulating lists in Racket: cons, first, and rest. But to get started, you want to know that empty, '(), and (list) are all ways to say “empty list.”

The CONS Function

If you want to link any two pieces of data in your Racket program, regardless of type, one common way to do that is with the cons function. When you call cons, Racket allocates a small chunk of memory, the cons cell, to hold references to the objects being linked. Here is a simple example where we cons the symbol chicken to the empty list:

> (cons 'chicken empty) '(chicken)

Notice that the empty list is not printed in the output of our cons call. There’s a simple reason for this: empty is a special value that is used to terminate a list in Racket. That said, the interactions panel is taking a shortcut and using the quote notation to describe a list with one element: 'chicken.

The lesson here is that Racket will always go out of its way to hide the cons cells from you. The previous example can also be written like this:

> (cons 'chicken '()) '(chicken)

The empty list, '(), can be used interchangeably with empty in Racket. Thinking of empty as the terminator of a list makes sense. What do you get when you add a chicken to an empty list? Just a list with a chicken in it. Of course, cons can add items to the front of the list. For example, to add 'pork to the front of '(beef chicken), use cons like this:

> (cons 'pork '(beef chicken)) '(pork beef chicken)

When Racketeers talk about using cons, they say they are consing something. In this example, we consed 'pork on to a list containing 'beef and 'chicken. Since all lists are made of cons cells, our '(beef chicken) list must have been created from its own two cons cells:

> (cons 'beef (cons 'chicken '())) '(beef chicken)

Combining the previous two examples, we can see what all the lists look like when viewed as conses. This is what is really happening:

> (cons 'pork (cons 'beef (cons 'chicken '()))) '(pork beef chicken)

Basically, this is telling us that when we cons together three items, we get a list of three items.

The interactions panel echoed back to us our entered items as a list, '(pork beef chicken), but it could just as easily, though a little less conveniently, have reported back the items exactly as we entered them. Either response would have been perfectly correct. In Racket, a chain of cons cells and a list are exactly the same thing.

The LIST Function

For convenience, Racket has many functions built on top of the basic three—cons, first, and rest. A useful one is the list function, which does the dirty work of building our list all at once:

> (list 'pork 'beef 'chicken) '(pork beef chicken)

Remember that there is no difference between a list created with the list function, one created by specifying individual cons cells, and one created with '. They’re all the same animal. But consider the following before you rush out and buy all available quotes.

The FIRST and REST Functions

While cons constructs new cons cells and assembles them into lists, there are also operations for disassembling lists. The first function is used for getting the first element out of a list:

> (first (cons 'pork (cons 'beef (cons 'chicken empty)))) 'pork

The rest function is used to grab the list out of the second part of the cell:

> (rest (list 'pork 'beef 'chicken)) '(beef chicken)

You can also nest first and rest to specify further which piece of data you are accessing:

> (first (rest '(pork beef chicken))) 'beef

You know that rest will take away the first item in a list. If you then take that shortened list and use first, you’ll get the first item in the new list. Hence, using these two functions together retrieves the second item in the original list.

Nested Lists

Lists can contain any kind of data, including other lists:

> (list 'cat (list 'duck 'bat) 'ant) '(cat (duck bat) ant)

This interaction shows a list containing three elements. The second element is '(duck bat), which is also a list.

However, under the hood, these nested lists are still just made out of cons cells. Let’s look at an example where we pull items out of nested lists.

> (first '((peas carrots tomatoes) (pork beef chicken))) '(peas carrots tomatoes) > (rest '(peas carrots tomatoes)) '(carrots tomatoes) > (rest (first '((peas carrots tomatoes) (pork beef chicken)))) '(carrots tomatoes)

The first function gives us the first item in the list, which is a list in this case. Next, we use the rest function to chop off the first item from this inner list, leaving us with '(carrots tomatoes). Using these functions together gives the same result.

As demonstrated in this example, cons cells allow us to create complex structures, and we use them here to build a nested list. To prove that our nested list consists solely of cons cells, here is how we could create the same nested list using only the cons function:

> (cons (cons 'peas (cons 'carrots (cons 'tomatoes '())))

(cons (cons 'pork (cons 'beef (cons 'chicken '()))) '()))

'((peas carrots tomatoes) (pork beef chicken))Since various combinations of first and rest are so common and useful, many are given their own name:

> (second '((peas carrots tomatoes) (pork beef chicken) duck))

'(pork beef chicken)

> (third '((peas carrots tomatoes) (pork beef chicken) duck))

'duck

> (first (second '((peas carrots tomatoes)

(pork beef chicken)

duck)))

'porkIn fact, functions for accessing the first through tenth elements are built in. These functions make it easy to manipulate lists in Racket, no matter how complicated they might be. If you are ever curious about built-in list functions, look in Help Desk.

3.5 Structures in Racket

Structures, like lists, are yet another means of packaging multiple pieces of data together in Racket. While lists are good for grouping an arbitrary number of items, structures are good for combining a fixed number of items. Say, for example, we need to track the name, student ID number, and dorm room number of every student on campus. In this case, we should use a structure to represent a student’s information because each student has a fixed number of attributes: name, ID, and dorm. However, we would want to use a list to represent all of the students, since the campus has an arbitrary number of students, which may grow and shrink.

Structure Basics

Defining structures in Racket is simple and straightforward. If we wish to make the student structure for our example, we write the following structure definition:

> (struct student (name id# dorm))

This definition doesn’t actually create any particular student, but instead it creates a new kind of data, which is distinct from all other kinds of data. When we say “creates a new kind of data,” we really mean the structure definition provides functions for constructing and taking apart student structure values. Within struct, the first word—in this case, student—denotes the name of the structure and is also used as the name of the constructor for student values. The parentheses following the name of the structure enclose a series of names for the components of the structure, and the constructor takes that many values.

Let’s create an instance of student:

> (define freshman1 (student 'Joe 1234 'NewHall))

Since the structure definition mentions three pieces, we apply the student constructor to three values, thus creating a single value that contains them all. This value is an instance, and it has three fields. Just as with any other kind of value, we can give names to structures for easy reference. If we ever need to retrieve information about our freshman1 student, we just use the accessors for student structures:

> (student-name freshman1) 'Joe > (student-id# freshman1) 1234

To access the information in a structure field, we call the appropriate accessor function. In this case, we want to pull the name from the student structure that we already created, so we’ll use student-name. As you can see, the interactions panel shows 'Joe, which is the value in freshman1’s name field. When you want to access a different field, you use the function for that field instead, say student-id#. As you may have guessed by now, the structure definition creates three such functions: student-name, student-id#, and student-dorm. We sometimes call them field selectors or just selectors.

In Racket, it is common practice to store data as lists of structures. Say we wanted to keep a list of all the freshman students in a computer science class. Since we could have anywhere from a handful to hundreds or thousands of students in the class, we want to use a list to represent it:

> (define mimi (student 'Mimi 1234 'NewHall)) > (define nicole (student 'Nicole 5678 'NewHall)) > (define rose (student 'Rose 8765 'NewHall)) > (define eric (student 'Eric 4321 'NewHall)) > (define in-class (list mimi nicole rose eric)) > (student-id# (third in-class)) 8765

Here, four students are listed and combined in a list called in-class. All of the list functions we discussed in the previous section still apply, and we see that we can still access the fields of the student structures.

Nesting Structures

It can come in handy to have structures within structures and even within lists. For instance, in our previous example, we could keep all the students in one centralized student-body structure for freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors, where each year stands for a list of student structures:

> (struct student-body (freshmen sophomores juniors seniors))

> (define all-students

(student-body (list freshman1 (student 'Mary 0101 'OldHall))

(list (student 'Jeff 5678 'OldHall))

(list (student 'Bob 4321 'Apartment))

empty))Here, we create the student-body structure with fields for the four different years. Next, we give the name all-students to one specific instance of student-body. As you can see, we expect lists of students in each of the four fields of a student-body instance.

To retrieve the name of the first freshman in the list, we need to properly layer our accessors:

> (student-name (first (student-body-freshmen all-students))) 'Joe > (student-name (second (student-body-freshmen all-students))) 'Mary > (student-name (first (student-body-juniors all-students))) 'Bob

We want the student-name of the first of the student-body-freshmen list. As we can see, 'Joe is the name of the first freshman we created before. This also works to get 'Mary and 'Bob.

Structures and lists are useful for many different cases, such as organizing data into meaningful compartments that can be easily accessed. In this book, we will be using structures and lists for almost all programs.

Structure Transparency

By default, Racket creates opaque structures. Among other things, this means that when you create a specific structure and use it in the interactions panel, it does not print just as you created it. Rather, you will see something strange:

> (struct example (x y z)) > (define ex1 (example 1 2 3)) > ex1 #<example>

If you want to look inside structures, you must use the #:transparent option with your structure definition. By some sort of magical process, you will then be able to see your structures in the interactions panel:

> (struct example2 (p q r) #:transparent) > (define ex2 (example2 9 8 7)) > ex2 (example2 9 8 7)

All of the structures in this book are supposed to be transparent, and therefore we don’t bother to show the option when we define structures.

Interrupt—Chapter Checkpoint

In this chapter, you saw most of the building blocks of Racket’s syntax and semantics:

There are many kinds of basic data, like Booleans, symbols, numbers, and strings.

You can make lists of data.

You can make your own, new kinds of data with structures.

You can mix it all up.