Liberation of Paris

I, carrying the twenty baited bottles in the wire basket, and Tatiana, the map, set off through the park to capture the little Berlin wilds and to steal apples for the staff dinner the Chief proclaimed for that joyous night: August 25, 1944. Paris had been liberated the day before by the Americans.

After all the bottles were placed, we hid behind the large shrub which concealed Mitzka’s secret passageway to the orchard, and I crawled through, ran to the trees, filled the wire basket with the green apples, made a bag of my white lab coat, tied it around my neck, stuffed it and my pockets and my shirtfront, then crawled back to her, on three paws, pushing the basket along, a most willing dog, holding the most beautiful apple, with a touch of red, in my other paw for her.

“Ah!” Tatiana sniffed the apple. “It smells just like apples.”

We laughed.

The celebration started after dark, at ten, in our Biology Lab, and was restricted to personnel from Genetics and Evolution, specials, and wives. The only exceptions were the Rare Earths Chemist, who worked for Mantle, and Marlene, who came with her husband, the Dutch Medical Student. Lab assistants were excluded. Sonja Press was there, of course, and Tatiana, who was special.

Flasks of flowers from Gunther the gardener decorated the tables, and there were baskets of the polished green apples; bowls of sunflower seeds from the greenhouse in the park; and, from the garden adjoining the greenhouse, plates of radishes, carrots, and tomatoes and bowls of boiled potatoes and green beans. There were platters of baked rabbit, basins of polenta, flasks of molasses, pitchers of hot tea, and, of course, beakers and beakers of vodka.

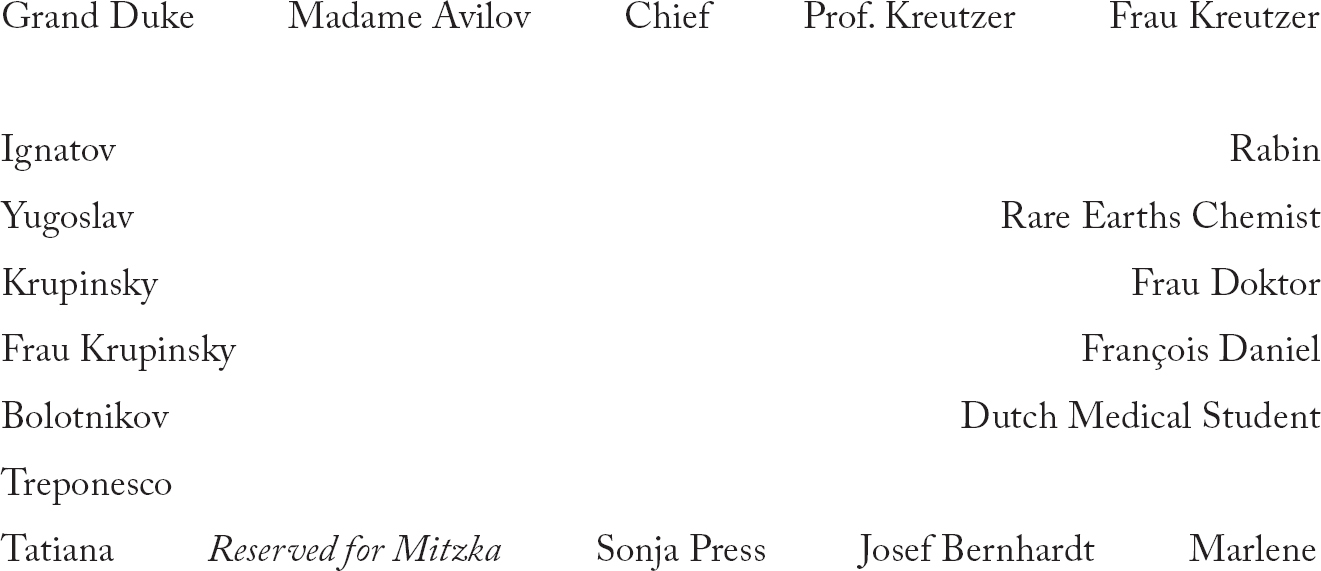

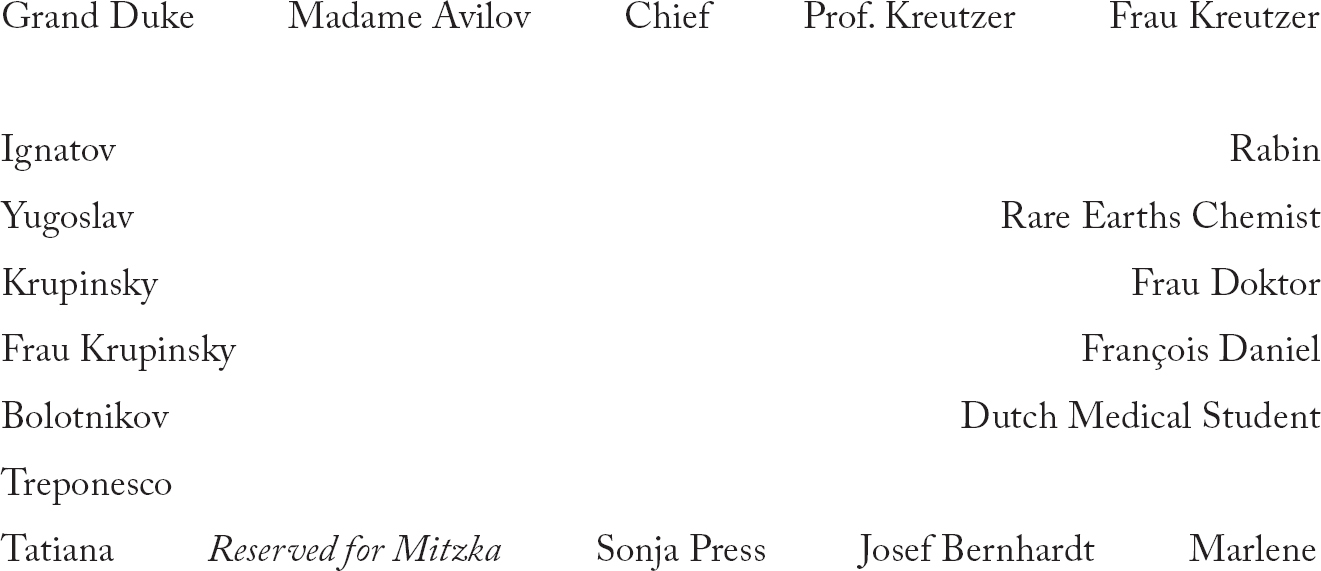

The tables were arranged in a square, with the seating as follows:

I did not even try to sit next to Tatiana, because she had put a flask with autumn weeds—chrysanthemums and snapdragons—on the plate next to her, a signal that Mitzka would appear. The Roumanian Biologist George Treponesco had as usual shoved his way to her other side by putting a chair at the corner, infuriating that fat dumpling Bolotnikov, who had forgone more prestigious seating in order to be next to her. The French Physicist François Daniel, who was also quite interested in Tatiana, had some perverted Parisian idea that to win a beautiful woman one must pretend to be “disinterested,” so instead of jockeying to be near her, he sat beside Frau Doktor and acted charming.

The dinner began as a jolly occasion. There were toasts to the Allies—especially to America—and many congratulations to François Daniel, who at one point gained everyone’s attention by shouting out. “We French were dealing the lethal blow!”

“Tell me one thing the French did,” yelled Krupinsky. “One thing!”

François Daniel stood. Head bowed, hand on heart, he said, “N’oubliez pas nos femmes.”

“Translate, you crazy poilu,” hollered Krupinsky.

“Don’t forget our women! They demoralized the entire German occupation army.”

“You’re damn right!” Krupinsky jumped to his feet. “They sucked them dry. To the women of France, a toast.”

All the men stood and drank and sat.

Madame Avilov, smiling, raised her glass. “I, too, will drink to the beautiful women of France and also to the men. They are wonderful, you know.”

“Madame,” said Krupinsky, “don’t you think you are going a bit too far?”

“No, I do not go too far.” There was light in her pale eyes. “The men of France are the most sensitive, the greatest diplomats in the world.”

Applause and boos. Laughter.

“Nikolai Alexandrovich, tell us your wonderful story about French diplomacy.” Madame turned to her husband.

“Ah, yes,” said the Chief. “You must all listen to this. At a banquet celebrating the fiftieth birthday of a reigning Queen, whose name I will not mention for the sake of tact . . .”

Laughter.

“. . . every country contributed a typical dish to the meal. The frijoles refritos from Mexico, the garbanzos from Spain, and so on, very soon affected the delicate digestion of the Queen. In a moment of silence, one could hear, very definitely from the seat of honor, the sound of air escaping.

“Immediately, the French Ambassador, purple-faced, was on his feet saying, ‘Madame, I beg you, mille pardonsrom, but my digestive system has been very labile. I have been warned by my doctor to eat bland foods but have been unable to resist these delicacies.’

“This, of course, was a serious diplomatic defeat for the other ambassadors present, and was particularly felt by the representative of the Third Reich, one Joachim von Ribbentrop.”

We all laughed.

“With a keen ear, he awaited another such happening from the royal presence, and when it occurred, he jumped to his feet, clicked his heels, and bowed, shouting, ‘Madame, this one and the next three are for the Third Reich.’”

Even Professor Kreutzer removed his glasses to wipe the tears of laughter from his eyes. Grand Duke Trusov jumped to his feet and said, “I propose a toast not only to the marvelous women, not only to the liberation of the most beautiful city in the world, but also to the greatest diplomats.”

Everybody stood but Krupinsky, even the women, and we waited for him, chanting, “Up. Up. Up,” until he, too, stood.

“I’ll drink to that,” he said. “But we must drink also to the Nazis, who are so incredibly stupid, thank heavens, that even the French can outwit them.”

All drank and laughed and wept and sat.

“My friends,” said Professor Kreutzer, “do not underestimate them.”

“You must admit, Max,” said the Chief, “they haven’t used their heads. Why didn’t they aim the V-One rockets at the ports and embarkation points for the Normandy invasion rather than at the civilian population of Britain? Correct? Or am I right?”

“Yes, of course you are right.”

“And now there stands between Paris and Germany—nothing. It is a matter of marching through. It should be very few weeks.”

Applause.

Professor Kreutzer stood and began to change to the black-rims.

All became quiet.

“My friends,” he said, “you must remember that also there was nothing between Normandy and Paris, and it took the Allies from June to August twenty-fourth to liberate that city. I wish also to remind you that we must proceed prudently as we always have done.”

“For the past year my pleading with you to cut consumption of fuel and water has been successful. Now I must plead that you use more. I do not want us to under consume so that our budget is cut or so that attention is drawn to what we do here. I should not have to remind you that since the twentieth of July, when the officers of the army revolted, the Nazi reaction has been fierce, and times are even more difficult. You all know this. The animal is wounded. The liberation of France will cripple it more. In its pain it will strike out. Caution,” he said. “Careful.”

He sat.

We began to eat in earnest. There was quiet discussion around the square of tables. Will it be the Russians or the Americans? Of course, everyone wanted to be liberated by the Americans. How long will it be until they come? Shall the windows be kept closed in order not to contaminate the wild flies in the park—the Drosophila melanogaster Berlin wild—with the pure-breds? How can one keep the females from ovulating and the male flies from ejaculating and losing their sperm load under anesthetic? What is the future of atomic power?

Abruptly, Tatiana jumped to her feet. “Shhh.” She put a finger to her lips. “I hear something.”

At once, all fell silent. Shouting in the park. Then machine-gun fire and rifles, a ratatatat and eight or ten single cracking shots. The blackout curtains were drawn, so we could not see out.

“Mitzka!” shrieked Madame. “Mitzka-aaaaa,” she wailed, rising to her feet.

“Shhh!” admonished Professor Kreutzer.

Electric silence.

Madame sat down again.

I glanced at Tatiana. All color had drained from her face.

“I’m getting the hell out of here!” The Roumanian Biologist George Treponesco jumped to his feet.

Treponesco sat down.

Professor Kreutzer stood. “Do not panic,” he said. “That is the worst thing you can do.”

“But I don’t want to get caught with these people,” said Treponesco, morosely.

“You will remain here,” said the Chief. “You will all listen to Max.”

Professor Kreutzer did not bother with a spectacle-changing routine. “Sonja,” he said, “telephone the Security Officer and tell him to meet me in the lobby at once.”

She ran to the phone in the corner of the lab.

Professor Kreutzer then addressed the Chief, but loud enough so that we all could hear. “Alex, I will go and see. You stay here and carry on as though it is a normal staff dinner. It would be foolish to act in haste.”

Sonja called out to Professor Kreutzer from the back of the lab, “He’s on his way.”

“Now locate Herr Wagenführer and tell him to be prepared to come over. Do you understand? We do not want him to come now, but he is on call.” Professor Kreutzer checked his pockets to be sure his spectacles were in place, then walked swiftly from the lab. It was eleven. We had celebrated for one hour.

There was no conversation now. All sat silent, listening for sounds from the park or from the corridor outside the lab. The Rare Earths Chemist excused himself. “I will be right back,” he said and left the room.

I went over to Tatiana and put my hand on her arm to comfort her. She shook me away. I returned to my place at the table. Did she imagine Mitzka in love with her? He sat by her at staff dinners only because she was the prettiest girl.

Sonja, after completing her call to Herr Wagenführer, pulled up a chair next to Madame, held her hand, and talked softly.

The Chief, without rising, lifted his glass and said, “Let us drink and eat while we wait.” But he did not drink.

Nor did any of us. There was occasional muted conversation around the table now but no eating and no drinking. Mostly we strained our ears to listen. No more shots. Men’s voices in the park, waxing and waning, then silence. Silence in the corridors until, half an hour after Professor Kreutzer left us, he returned, followed by the Gestapo in the House in his black uniform of the S.S., carrying a red balalaika in one hand. Mitzka.

All talk stopped. I had never seen the Security Officer at a staff dinner before. The Chief jumped up. His chair fell. Professor Kreutzer rushed to his side and put a restraining hand on the Chief’s arm. The Security Officer limped to where they stood at the head of the table and held out the balalaika. His mouth was open. No words. He trembled.

“Speak!” roared the Chief.

“I didn’t know. I knew nothing. He was denounced by someone here, but it was not I. I swear it.”

Professor Kreutzer cautioned the Chief with a raised finger and a shaking of his head.

“They got him outside. They caught him at the back of the park,” said the frightened man.

“Who was it?” The Chief grabbed the black lapels and pulled the Security Officer toward him.

“Alex,” said Professor Kreutzer, “I will tell you. Please sit down.” He said a few quiet words to the Security Officer, took the red balalaika from him, and placed it on the table before the Avilovs.

The Security Officer left the lab.

Professor Kreutzer leaned over between the Chief and Madame and spoke softly to them. When he was through, the Chief stood to tell us.

“My friends”—he paused and looked around the tables as though to embrace each and every one of us—“Max informs us that the Gestapo have shot him. They say he ran into the park trying to escape and that he is dead.”

The Chief bent his body. His large hand encompassed his glass of vodka. He shrugged, and, body still bowed, he raised his head to see us. “I am too sad to be proud. I am too sad to be angry. Mitzka was a man. He did as he wished, knowing the consequences.” He stood straight, raised the glass. “A Gestapo in the House does not always save one from a Caesarean section.” And he threw the vodka down his throat, then smashed the glass on the table. He cut his hand.

The Russian pianist, Stanislas Rabin, sitting next to Frau Kreutzer, stood, drank, and threw his glass, with great force, onto the floor. Each man, in turn, did the same: Professor Kreutzer, the Grand Duke, Ignatov, the Yugoslav, Krupinsky, Bolotnikov, Treponesco, the Dutch Medical Student, François Daniel. I, too, in my turn. All but the Rare Earths Chemist, who had not returned. The Chief picked up the red balalaika from the table and carried it to where I sat. His hand was bleeding profusely.

“Play!” he said, shoving it into my hands.

“I don’t know how.”

Mitzka had tried to teach me, but it was not my music. Tatiana jumped up, grabbed the balalaika away from me, and began to play a rhythmic folk melody, sad and in a minor key. Russian. Bolotnikov sang along—without words—with a “Yah, dee, dah, deedah.” The Yugoslav stood and swayed in time to the music, then jumped onto the table, and, in the midst of all the plates and bowls and beakers, he danced.

Professor Kreutzer, raising his voice to be heard over the noise, said, “Krup, you’d better take a look, at Alex’s hand.”

“Josef, come along,” said Krupinsky tersely, and the Chief, Professor Kreutzer, Krupinsky, and I moved to a dark corner of the lab where most of the medical supplies were stored.

The Chief insisted on standing. I held a lamp while Krupinsky tweezed out the glass, cleansed, stitched, and bound the wound. It was a deep cut in the web between thumb and forefinger of the right hand. “It will be five or six stitches. Would you like a local?”

“Sew it up,” growled the Chief, “and hurry. Are you certain,” he said to Professor Kreutzer, “that he has not gone to lead them up here?”

“I checked in Rare Earths. He made it quite obvious that he took a supply of strophanthin with him.”

“Then he plans to kill himself.”

“Latte is positive that the denunciation was only against Mitzka and his companion—and done only to save himself. It seems the Gestapo had been pressuring him for information.” Latte was the name of the Security Officer.

“I hope he waits to take the strophanthin. If he dies too soon, it will draw attention to us. Damn it, Krup, aren’t you through fiddling with my hand yet?”

“Hold still, damn it. Two more stitches.”

“Obviously, they need to be fed more denunciations,” said Professor Kreutzer. “We have become careless.”

“Ah, yes, the gods must have sacrificed to them so many virgins, so many youths. We could try the alcohol again.”

“We’ve done that too many times. Let me think about it.”

“Hold still, Chief, please. I’ve just got to bandage it. Josef, hand me the gauze—and hold that lamp still!”

“Do you know the name of the other lad?” the Chief asked.

“Schmidt. Dieter Schmidt.”

“What will they do with him?”

Professor Kreutzer shrugged.

“Are you sure they will not search for others?”

“No. Latte told me that they knew there would be two only—Mitzka and the Schmidt boy. They are propitiated. And Alex, they were told by our friend, most clearly, that the denunciation of your son and his ‘comrade’ came from you because of your hatred of Communists and your devotion to Adolf Hitler. I corroborated this tonight. You will be called upon to do the same.”

“Corroborate,” muttered the Chief.

“I will. I will. Is there anything we can do for young Schmidt?”

“Nothing. He’s as good as dead.”

“He’d be better off dead. Ask our Gestapo in the House if there is anything we can do.”

“There’s no use, Alex. We must not endanger the rest by contradictory actions.”

“At least ask Latte. That can do no harm.”

“It’s done, Chief,” said Krupinsky. “You might want your arm in a sling to keep from banging it.”

“No, thank you, Krup. Thank you very much. Max, what of Mitzka?”

“They would not leave the body. I made a small plea for the sake of Madame. I’m sorry. I could not push them.”

“Of course not. Krup, I want you to give Madame a sedative—a strong one.”

“O.K. Will you be taking her home?”

“What do you think, Max, is it safe to walk her across the park?”

“They are gone, I tell you. They have what they came for.”

Sonja Press and Frau Doktor escorted Madame Avilov home and stayed the night with her. Krupinsky went along to administer a sedative, then returned to the lab. Professor Kreutzer, who also had a house in the park, took his young wife home and returned at once. He never allowed her to stay for the parties. I don’t blame him. She was much younger than he and very pretty. The Dutch Medical Student and Marlene went home.

The Chief and everyone else stayed on. The girls from Die Scala showed up near midnight. By that time an accordion and another balalaika had appeared, the tables were pushed against the wall, the glass was swept under the tables, and the party had begun in earnest. At first, Professor Kreutzer preached caution. “Careful,” he said, removing his spectacles and looking severe. The Chief, beyond reason, would not listen, and ordered me to fetch more jugs of vodka from labs on other floors. They drank and danced, wild Russian dances, all but Professor Kreutzer, the Krupinskys, Tatiana, and me. Tatiana was perched on a worktable, her feet on the chair, playing Mitzka’s balalaika; I stood near her. Mitzka was, of course, running to escape through the apples when they shot him.

The wake became so wild, that Tatiana—Tanya—still playing the balalaika, sidled over to the edge of the table, nearer to me. The clowns had begun to line up to pay her drunken court, and I think it made her feel uneasy. One of the first was the Frenchman, François Daniel: he muttered a few quiet words to her, then stopped in front of me.

“You will never win her,” he said. “Never,” he repeated. “You will never learn to keep the distance until she is ready.”

When the greatest buffoon of them all, the Roumanian Biologist George Treponesco, staggering drunk, paid his call, squatting at her feet, embracing her legs, she completely recoiled in disgust. I disentangled his arms from her legs and pushed him backward onto his derrière, and she, holding the balalaika above her head to keep it from harm, jumped to her feet and took my arm. That ass Treponesco rolled over and actually crawled away on all fours.

We joined Professor Kreutzer and the Krupinskys, who stood near the door, stonily staring at the bedlam. The lab was a disaster. Drinking was encouraged at staff dinners, and, usually, there was a strenuous party afterward with the ballet girls and all, but it was always within some sort of limits. Everyone would help clean up from the dinner, put everything away, and push the tables back in place, so that next day the routine work of the lab could be carried out. That was most important to the Chief, the research. But oh, my good Lord, the tables had been shoved back helter-skelter with all the food and dishes still on them, there was broken glass everywhere, and the Chief was as I’d never seen him. He always drank a lot, but I had never seen him drunk before, and there he was, squatting on the floor, trying to do the tcherzatskaya, but so looped he had to be held up by two Die Scala girls, one on each side. His great head was thrown back, his mouth opened wide while Bolotnikov poured vodka down his throat. The others were drinking and jumping and shouting and clapping, encouraging him. He always danced the tcherzatskaya for us—we all loved it when he did this—but he’d never needed anyone to hold him up. He was panting like some great beast; his face was beet red, and he was sweating copiously.

“He’ll have a heart attack,” said Krupinsky, tapping his own chest, as though he were in pain.

Professor Kreutzer pointed to the door. The Krupinskys, Tanya, and I followed him down the hallway until it was quiet enough for us to converse in low voices. Tanya had taken Mitzka’s balalaika with her for fear it would be broken in the frenzy.

“How long,” Professor Kreutzer asked Krupinsky, “can they keep this up?”

“Hours—it’s after one thirty now—there’s no way of knowing.” He tapped his chest, again, as though he were in pain.

Professor Kreutzer took a glasses case from his breast pocket, removed from it the black-rims, which he held to the light, squinting at them through the gold-rims he was wearing; then, instead of cleaning the black-rims—which was the next step in the routine—he shoved them back into the case and into his pocket. “The best thing we can do is get some rest. I will stretch out in Physics. I suggest that all of you find a quiet place. It’s too late, in any case, to get the train.”

“I will go to my room,” Tanya said. It was in a building in the park.

The door to our Biology Laboratory opened, and Rabin stepped timidly into the hall, looking this way and that before walking over to us and making a brief statement in Russian.

“He says,” Krupinsky translated, “that he is not very drunk.”

“Ask him how much longer it will go on.”

“He doesn’t know,” translated Krupinsky. “Two hours, three.”

Rabin shrugged apologetically and spoke again. This time Tanya translated. “He will play for us,” she said.

“Fine,” said Professor Kreutzer. “I will be in my lab if you need me, and I will meet you, in any case, at seven, in the cafeteria kitchen downstairs.”

The Krupinskys, Tanya, and I followed Rabin down the stairs and into the parlor. Krupinsky and his wife nestled close together on one couch; Rabin settled at the piano, eyes closed, head bent, as though asleep; Tanya and I sat apart on the same couch. She held Mitzka’s balalaika on her knees. Rabin hit the keys and the hair on the back of my neck stood up: an orgy of Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky—magnificent, technically perfect, passionate, some pieces over and over without stopping.

Berlin is cold at two o’clock in the morning, even in August. I left the parlor long enough to fetch two woolen blankets from the bomb shelter in the basement. I tucked one around the Krupinskys, huddled lovingly together. Frau Krupinsky kissed my cheek. The other I took to where Tanya sat, tight against the end of the couch. She put Mitzka’s balalaika down beside her, where I had assumed I would sit, took the blanket from me, and covered herself. I could have fetched another for myself, but I did not. And I did not sit again on her couch, but chose, rather, to listen until dawn from a hard chair as far from her as possible.

At seven, Professor Kreutzer joined us in the cafeteria kitchen and, over a hurried cup of tea, gave us instructions: Krupinsky was to check to see how Madame Avilov was doing, then see if Sonja and/or Frau Doktor could be spared to help with the cleanup, which Tanya and I were to begin at once.

The Krupinskys left to cross the park to the Chief’s house. Professor Kreutzer, Tanya, and I walked through the lobby just as Grand Duke Trusov came down the front stairs—a Die Scala dancer on each arm—looking for a cup of tea. He glanced out the windows, dropped his dancers, and came tearing toward us.

“Max!” he shouted. “An inspection team!”

We all ran to the windows. Three black cars—two Mercedes and a Horch—were coming around the circular drive.

Professor Kreutzer snapped orders: “Tatiana, run after Krupinsky and tell him to come back. You, Duke, find Alex—he’s probably asleep in his office—and tell the dancers to vanish.” To me, he said, “Telephone the Security Officer and tell him to hurry over. Quickly.”

I raced up the stairs to the phone in my lab, then decided it would be safer to use the private telephone in the Chief’s penthouse office. Grand Duke Trusov was already there bending over the Chief, who was collapsed on the floor, clad only in a shirt, a Die Scala girl naked in his arms. The Grand Duke couldn’t waken either of them. He was slapping their faces and dousing them with cold water.

“Bernhardt,” he ordered, “run down to my lab and get some vodka. That will wake him up.”

Through the window, I saw the Krupinskys running across the lawn. I telephoned the Security Officer. Krupinsky came dashing up the outside steps to the penthouse and into the office.

“Good Christ, Duke!” he shouted. “What are you trying to do, drown him?” Krupinsky turned to his wife. “Run to the lab and get my stethoscope and sphygmomanometer.” He knelt beside the Chief to take his pulse. “Listen, Duke you go down to Chemistry and get me two ampules of Polybion, one Bexatin Fortissimum, and one Cebion Forte.”

“Vitamins?” shouted the Duke. “Vitamins? Why don’t you give him a shot of Adrenalin?”

“I want to wake him up, not kill him, damn you. His only son got murdered last night, he is dead drunk—what the hell do you think his blood pressure might be?” He turned to me.

“Josef, run along to the lab and get a new sterile syringe, needles, cotton, and alcohol.”

My good Lord, the lab was in chaos: rabbit bones, broken glass, dirty dishes, congealed polenta, apple cores, Bolotnikov asleep under one table, and the Roumanian Biologist George Treponesco and a girl under another. Tanya had begun to clear away the mess on the worktables. The morning sorting of Drosophila would have to be done no matter what else was going on.

I hurried back to the penthouse.

“One hundred sixty over one hundred and ten,” said Krupinsky. “Lift the girl off and help me turn him over.”

The Chief muttered and shook his head at the needles but did not wake up.

“I want to get his head down. Don’t want his aspirating vomitus.”

We wrapped the Chief in a blanket, dragged and carried him through the outer office, and laid him on his stomach down the stairs. Grand Duke Trusov and I, at the top of the stairwell, held his feet, and Krupinsky sat by his head, talking quietly.

“Hi, Chief. Time to get up. Good morning. The sky is blue, and we have visitors.”

The leonine head shook away the sound.

“Good morning, Chief. Another day, another dollar, your pulse is steadier, time to get up.”

Eyes opened. Blink.

“Good morning, Chief. How’s the head?”

Blink. “Krupinsky, is it true that I am hanging down the staircase?”

“True.”

“I cannot understand what this fuss is all about. I was extremely tired and was only resting.” He tried to jump to his feet, but, of course, it was impossible. Head down again, eyes closed. “Tell them to let go of my feet.”

“Just a minute, Chief. We have a logistics problem. Listen, Duke, you and Josef swing his legs around, and for Christ’s sake, both of you move in the same direction—I’ve got his shoulders: Christ, Chief, you are heavy—and let’s get him all on one stair.”

The Chief sat up. “Take this damn blood pressure cuff off me,” he growled. “Why didn’t you let me sleep?”

“Chief, there’s an inspection team downstairs,” said Krupinsky.

“What is it they want?”

“I don’t know,” said the Grand Duke. “Max is with them.”

“All right.” The Chief jumped to his feet, wrapping the blanket around himself. “Josef, be a good boy and brew me a pitcher of tea. Strong. And bring it to me in my shower. And Krup, will you stop fiddling with that damned stethoscope. There’s nothing wrong with me.”

The dancer was still asleep on the floor of the Chief’s office. Krupinsky took her blood pressure, and then he and the Duke wrapped her up in a blanket and carried her to the darkroom on the third floor, leaving Frau Krupinsky to watch her.

The Chief drank the first four cups of tea under water. When Professor Kreutzer stepped into the bathroom, the Chief emerged from the shower holding the fifth cup. He beckoned to me to hand him the huge bath towel hanging on a hook, and gave me, in exchange, the cup and saucer. “What is it they want, Max?” He began to dry himself.

“It is, again, the Ministry for the Coordination of Total War Effort—eleven ‘inspectors.’ They want, and I quote them, ‘to see the linear accelerator and know its place in the atomic potential of the Third Reich.’”

“Are they scientists?”

“Only one. He’s not a physicist, but a biologist, and not quite as stupid as the rest. The others are the average Party officials—grocers and schoolteachers. I told them, of course, that the work here is Top Secret and that they must undergo strict security clearance—which would take some time, several hours or so. Latte is interviewing each one separately, then checking their clearance. He will let six or seven through, but for sure not the scientist.”

“Our Gestapo in the House is not too useful, is he?” The Chief enveloped himself in the great white towel.

“He’s as surprised as we.”

“This inspection has nothing to do with what happened last night?” the Chief asked quietly.

“No. I am almost certain it is coincidental, although both are reactions to the twentieth of July and to the liberation of France. It will get worse.”

The Chief nodded, grimly. “I see. What time is it?”

“Eight fifteen. The security check will keep them busy for at least another hour.”

“How much time do we need to get the Biology Lab cleaned up, the flies sorted, and a demonstration made ready in the Radiation Lab?”

“As much time as you can give me.”

“Then I will lecture to them in a meeting room on the first floor for three hours.” His hair still dripping wet and plastered onto his forehead, the huge white towel wrapped about him like a toga, the Chief raised his right arm and began an oration in his penthouse shower room. “I will begin with Empedocles and Democritus, from the Greek atomos, ‘indivisible,’ hence, ‘that which cannot be split,’ and on through Dalton and Thomson and to our good friend, Niels Bohr, with his simplistic image of a miniature solar system, with its planetary electrons in circular orbit about the nucleus, but one must not mention Einstein to the officials from the Ministry for the Coordination of Total War Effort of the Third Reich. No! But I will say that now, with all we know since Democritus, we are unable to measure to conjecture, for it is wave yet particle, empty yet full, forward yet backward. It trembles, sputters, radiates, expands, collapses, splits, absorbs, discharges, and reappears. And though we cannot define it, we can release, in theory, its power. And then I will give them an equation, a formula for population casualties—I’ll need a blackboard for that—and I’ll tell them about fallout, retombées radioactives, radio actionye ossadkye. Then I’ll show slides, myself.” He looked at me.

“Hide this boy,” he said, “and the others. Tell our Alsatian friend to switch the records of all our specials and keep them out of here.

“I will show them slides of radiation burns, of destroyed bone marrow, of grotesque mutations in rats. I will talk for exactly three hours. And then, Max, you can put on a show in the Radiation Laboratory, after which we will serve them dinner in the dining room downstairs and answer any questions they might have.”

“I’ll need the boy,” said Professor Kreutzer.

“No. Let him hide upstairs with Krup. We have lost enough boys.”

“I need him in the Radiation Laboratory. He will be all right.”

I was to remove the shielding from the ultraviolet lamp, a mercury-vapor arc enclosed in quartz, so that it would fill the room and do two things: make the air smell of ozone and make certain things glow—teeth, buttons, fingernails, and the collection of minerals I took from the Rare Earths Laboratory. The Rare Earths Chemist was not there, so I had to take them myself.

When I was finished with that, Professor Kreutzer and I rigged up an old spark rectifier which had a point as an anode and a flat plate as a cathode, and when it reached approximately 250,000 volts, a spark jumped almost twenty inches every ten or fifteen seconds. And then we reconnected an old x-ray tube whose anti-cathode was radiation-cooled, so after a while it emitted very bright lights.

After that, we tidied up the Radiation Laboratory: picked up the tools, oil rags, glass tubing, and all the other junk lying around on the floor.

Finally, we tested our equipment and had a dress rehearsal of our light show, beginning with Professor Kreutzer and his terrifying lightning arrester. Even without our theatrical tricks, the Radiation Laboratory was a frightening place, with its high-tension, high-voltage equipment. It is ironic, though, that the greatest danger—the radiation—is not picked up at all by the senses.

These preparations and the rehearsal took until noon—well over three hours—and when Professor Kreutzer had no more use for me, I went into my lab. They seemed to have everything under control. Sonja, the Krupinskys, and the Yugoslav were carrying the last of the dishes, all washed and dried, down the hall to Physics, where, most likely, they wouldn’t be noticed among the junk. Tanya and Frau Doktor were sorting the flies.

I walked over to them and said, “Good afternoon.”

Tanya ignored my salutation.

Frau Doktor turned to me. “Good afternoon, Josef. How are you?”

“Fine, thank you, Frau Doktor.”

“He was a close friend of yours, wasn’t he?”

“We were schoolmates since I was nine—and friends since I was twelve.”

“He is . . . was your age then?”

“Older. Mitzka was almost twenty.”

Tanya twisted in her chair and looked up at me. “And you are eighteen!” she said unpleasantly.

“He was a brave young man,” said Frau Doktor. “A great loss.”

“He was a hero!” snapped Tanya, accenting the he.

“And I am a coward!” I answered, accenting the I.

“I didn’t mean it that way,” she said.

“Oh? What did you mean?”

“Please,” said Frau Doktor. “This is no time for dissension.”

Tanya jumped to her feet and walked quickly to the far corner of the lab. I followed.

She had deep shadows under her eyes, making them look bigger, and her thick long hair was working loose from the green ribbon that always held it back. I wanted to put my arm about her to comfort her.

“Do you really want to know what I’ve been thinking?” she said.

I nodded.

“May I be frank?”

“By all means.”

“I think that you waste your time and talent.”

“What has that to do with my cowardice?”

“Nothing. I don’t know why I said that. And Mitzka . . . he was brave, but also very foolish.” She began to cry. She was so very tired. “His activities with the underground are one thing, but coming back here—to show off—was another. It was dangerous for him and put all of us in jeopardy—his own father and mother! He put my life in danger. My life! He was a fool!” Tanya sobbed.

“I didn’t know you felt that way about him. I thought—”

“You thought I was in love with him. Well, you don’t know the first thing about me, Josef Bernhardt. Everybody loved Mitzka. He was dazzling. But there is a difference between loving someone and being ‘in love’ with someone.” Tears were streaming down her face. “And besides, I don’t think he was capable of loving anybody—but himself.”

Ah, so she knew he didn’t love her. I put my hand on her arm to comfort her, but she jerked violently away from me.

“And you,” she sobbed. “Josef, I don’t think of you as a coward.”

“And how else can you think of me, hiding here under the umbrella of his father, while Mitzka loses his life to help others?”

“How do I think of you?” she said in a quiet, quavering voice. “I think of you as brilliant. I have been told that you have a genius for mathematics—that you could be a great mathematician. But you are already eighteen years old and would have to begin to work for it now.” She took a deep, shaking breath. “But instead, what do you do? You waste your time. You go to the darkroom with every girl at the Institute.”

So that was it. “Every girl?”

Her tears had stopped. “You know what I mean.”

What could I say? “Every girl” was a gross exaggeration. As a matter of fact, since Marlene got pregnant, Monika was almost the only one who actually had sex with me in the darkroom. The others whom I had been seeing regularly—two girls from Chemistry—had an apartment in the village of Hagen and insisted I come there. It was awkward: I had to climb up the drainpipe in the dark, after their landlady was asleep, and sneak out again before she woke up. I would have preferred the darkroom, but every girl had her own form of discretion.

“If you wonder why I have not been sitting by you at the staff dinners, it is because I can’t stand men who cannot control their animal appetites.”

“Yes?” I said sarcastically. “And yet you sit by that Roumanian, Treponesco?”

“I don’t care about him!” It was a wail.

There was a commotion at the door to the lab. Professor Kreutzer had just come in with Herr Wagenführer, who was clapping his hands to gain everyone’s attention: “Attention, everyone. The following people will report to the Luftwaffe, Squadron Clerk, Sixth Floor, for work assignments for the remainder of the day: Professor François Marie Daniel, Tatiana Rachel Backhaus, Eric van Leyden, Professor Igor Vasilovich Bolotnikov”—he paused and took a deep breath—“and Professor Dmitri Varvilovovich Tsechetverikov. At this time, I cannot tell you how long before you can go back to your regular work. You will be informed. Hurry, there is no time for questions. Josef Leopold Bernhardt?” He looked about for me.

“Here!”

“You will be employed by the Mantle Corporation today and are assigned to Professor Kreutzer here. Make haste, all of you. There is no time.” He clapped his hands again.

“What about my wife?” shouted Krupinsky, as the specials hurried from the room. “She’s here, too.”

“Darkroom,” said Herr Wagenführer, as he hurried from the lab.

The Chief, finished with his three-hour lecture, escorted the inspectors to the hallway outside the Radiation Laboratory, where Professor Kreutzer dressed them elaborately: extra lead plates over their genitals; lead aprons around their shoulders like a cape, covering their entire bodies; safety glasses. In through the pneumatic doors they walked, smelling the ozone, seeing the purple phosphorescent glow, and Professor Kreutzer with the lightning arrester making sparks, crackles, bangs, hisses, and lightning, and the sparks flying, the bright lights emitting from the x-ray tube, and the corona glowing about the high-voltage condensers, cold colors of the spectrum—blue, white, violet. And I, hidden in the dark control booth, pulled the levers. Through the thick windows of glass and water, I could see the purple phosphorescent glow of the teeth of the inspectors from the Ministry for the Coordination of Total War Effort.

Fingernails and buttons glowing, and teeth in the grimaced faces, the seven inspectors who passed our Gestapo’s strict security check huddled, terrified, in a corner of the Radiation Laboratory, as far from the linear accelerator as they could get. The biologist was not among them. Did they think we had enough energy to make a bomb, when in reality all we could do with the little atom smasher Professor Kreutzer made, himself, out of bits and scraps, was irradiate a few flies—if they were left long enough on the target?

The Chief often said that Adolf Hitler must have astute advisers who told him, all along, that Germany did not have the capacity to develop these weapons. On the off chance, however, heavy water was made available from Norway, and a small amount of experimentation was allowed, as if someone was hoping for a miracle, some breakthrough, afraid to let go altogether, for, after all, it was all there in theory. But the technical aspects—anyone with any kind of a brain and some basic knowledge knew that technically it could not be achieved without untold space and untold wealth. But these people were desperate, looking for some miracle to help them, hoping they were seeing it in the purple phosphorescent glow.

We hadn’t even turned on the linear accelerator. Why take the chance, Professor Kreutzer said, that one of the inspectors would be harmed by the radiation or why take the chance that the linear accelerator, itself, would be harmed by the high voltage I was throwing through? After all, it was the center of the Institute. The Chief said it often enough after a vodka or three: “This place is a cow with three hundred teats,” he would bellow, “and the linear accelerator is the bull, and with the coupling of the two, Max and I have pressure over some government officials who have interests in certain businesses which produce things—counting amplifiers or pumps, for example. But to produce these counting amplifiers and pumps, these businesses need raw materials and labor, and for this they need authorization permits, which must be issued by other government officials who, in turn, are made silent partners in the businesses which produce the counting amplifiers and pumps, and who, therefore, are interested in finding research projects which need the products that happen to have the exact specifications of those manufactured by the businesses.”

I thought it like the Contes de ma mère l’oie—the Mother Goose Mother had read to me when I was quite young. It wasn’t “The House That Jack Built,” but, rather, “The House That Fission Built”: This was the house the scientists built, that enriched the government officials and the manufacturers, who protected one another and the Institute, that protected its scientists and workers, who used the Radiation Laboratory to retard the cancer of the Gestapo in the House, who, in return, kept the Chief and Professor Kreutzer informed, and who cleverly denounced the Institute in small, intelligent, harmless ways, regularly enough to keep the pressure off. For example, it was the Security Officer who requested—at the suggestion of Professor Kreutzer—that the ethyl alcohol be delivered adulterated with petrol ether. But it was not he who offered Mitzka as the scapegoat. It was, of course, the Rare Earths Chemist. He had been harassed for information. Denouncing Mitzka, he must have felt, would take pressure off him without jeopardizing the good, secure life he enjoyed at the Institute.

One month after Mitzka’s murder, the police telephoned the Institute to report that an employee had died of a heart attack the night before in a public air-raid shelter during an air raid. The Rare Earths Chemist had waited one month to take the strophanthin in order not to draw attention to the Institute.

By that time, the Roumanian Biologist George Treponesco had already been transferred into the Rare Earths Laboratory, Tanya to that of Frau Doktor to assist with the larval transplants, and Marlene was recalled to work in our laboratory. Her mother took care of the baby.

Professor Kreutzer’s prophecy at the celebration dinner that times would be even worse, that the Nazi reaction to the liberation of Paris would be fierce, was correct. They did strike out in every direction, increasing their efforts to round up and exterminate what remained of the Jews, during those last nine months of the war, from August 1944 until April 1945, when the Americans stopped—just stopped—when they could have marched through with so little resistance and saved so many. Uncle Otto and Aunt Greta, for example.

Uncle, bent over from the pain in his neck and back and extremely agitated, was waiting for me outside his apartment building. Face red, arms waving wildly, he blurted out in a loud, quavering voice, “You must be a good boy and bring us tomorrow two wool blankets and some soap—for the trip. Is it too much trouble?”

“Uncle. Please! Calm down and tell me. What trip?”

“If it’s too much trouble, I understand. Two blankets and some soap. We have the rest.”

Because his building was across from the Farmers’ Market, there were many people on the street, and his excitement was drawing their attention. “I will bring whatever you want, but it would be better to talk about it upstairs.”

“No! No! I don’t want you to upset your aunt.” He shoved an envelope into my hand. “This came yesterday.” Uncle Otto was so weak, and in such pain, that his legs trembled and he hardly could stand.

I put a hand on his shoulder and gently propelled him through the door of the apartment house. Although it was a cool evening, it had been a rare warm day for September, and the heat had amplified the putrid air in the building. “Sit here on the steps, Uncle.” I helped him to lower himself onto a stair, then opened the envelope.

While I read, he chattered nervously. “I served the Kaiser loyally. I was decorated for bravery in the First World War. I am sure I will not be harmed. The Jacoby family have been good German citizens since the beginning of the fifteenth century. That’s almost five hundred years.”

GERMAN INTERIOR MINISTRY

DEPARTMENT OF THE DELEGATE

FOR SPECIAL DEPLOYMENT

18 September 1944

Herrn Otto Israel Jacoby, and

Frau Margaret Sara Jacoby née Braunstein

Berlin Alexanderplatz

Grosse Frankfurter Strasse 47 Fourth

You are herewith advised that you have been selected for special employment for the general war effort of the German Reich.

You have been assigned the following numbers:

Otto Israel Jacoby |

236 |

Margaret Sara Jacoby née Braunstein |

752 |

and are expected to be ready for transportation on 21st September at 2 a.m. to a location that will be announced to you at an appropriate time.

Your baggage is limited to 10 kilograms each and should include heavy work clothes and provisions for three days.

Noncompliance will be severely punished according to special provisions by the Law.

With German Greetings!

[illegible signature]

“Uncle, do you know what this means?”

“Yes. Yes. I must do as they say.”

“You can’t let them take you. You must hide. And Aunt Greta.”

“No, no, Josef. Look.” He reached up and took the summons from my hand. “See, they say we are to be employed. And it is so polite—they send greetings.”

“Uncle, they are always polite.” There he sat, a brace from his chin to his tailbone, weak and in constant pain. Heavy work clothes! “Let me go up and get Aunt Greta, and I will take you to our house, to Father. He will help you.”

With great effort, he pushed himself to his feet. “No, we could not do that. We must obey the law. Remember your Uncle Philip. We must do as they say. I was decorated by the Kaiser for bravery. They will send us to Theresienstadt.”

Theresienstadt. I could not believe I was hearing this. I shoved my rucksack with their weekly supply of food, money, and ration stamps into his arms, dropped the bag of groceries I had just bought, and, before he could say another word, fled out the door and back to the Farmers’ Market, where I walked back and forth among the stalls. It was inconceivable that he didn’t know. Wasn’t everyone aware that the Nazis put up facades—Potemkin villages, Theresienstadt—advertised as places for certain people who were “acceptable” despite being Jews, people who would be “reabsorbed” when the rage against the Jews subsided? It was all fantasy. There was no one place big enough for every Jew and other undesirable who thought he was special. And besides, going to Theresienstadt was no guarantee—conditions there were horrible and getting worse. Shortly before his death, Mitzka had told me about it and about the jammed boxcars with unhygienic conditions beyond all imagination. Surely, Uncle knew what this really meant.

At a flower stall I bought six yellow gladiolas for Aunt Greta and raced back to their building. Uncle had started the long climb, and I found him on the third-floor landing, leaning against a wall and panting. I took back my rucksack and the bag of groceries and put an arm about him. He leaned heavily against me as we climbed slowly up the last flight to his fourth-floor apartment.

“Don’t upset your aunt,” he pleaded.

“Does she know?”

“Yes. But don’t upset her more.”

She was waiting for us outside their apartment. “Aunt Greta, please, talk some sense into Uncle.”

“I am sure we will not be harmed, Josef. Don’t worry. Your uncle served the Kaiser loyally and was decorated for bravery—”

“I know, Aunt, but that means nothing to these swine.”

“Hush!” said Uncle Otto, who seemed more in control of himself now that he had his beloved wife to protect. He opened the door to the apartment, and we all went inside. “I have some things for you.” He hobbled over to the dining table in front of the window, where there were two packages neatly wrapped in old newspaper.

“Uncle, listen to me.” I put the grocery bag on the table. “Every day when I walk from the village of Hagen to the Institute, I pass a labor camp—barracks, really—where they have workers from France. They work for the hospital, and they are free to come and go. You speak French like a native. Come with me. Now. Come on the train, you and Aunt, and just walk into the place. They wouldn’t even notice you.”

“Josef,” he said in a patronizing way, “in the first place, you know your aunt doesn’t speak one word of French—”

“She could keep quiet. Really, they wouldn’t even know.”

He held up his hand to silence me. “I have something for you.” He patted the news wrapped packages on the table.

“Uncle—”

“Shhh.” He picked up the larger bundle. “Handel,” he said, “the Concent Grossi. These are my favorite. I want you to have them.”

“Uncle—”

“And this”—he picked up the smaller packet—“this is a prayer book. It belonged to your grandfather Josef Jacoby, after whom you are named.”

He shoved them at me. “Take them.”

I was still holding the yellow gladiolas. “Uncle, listen to me—just for a minute.”

“No, Josef. You listen to me.” he said firmly. “Sit down, please.” He lowered himself onto a chair, but I refused to sit with him. “In the book is a paper with the dates of the deaths of your grandmother and grandfather Jacoby. On the anniversaries of their deaths, I ask, as a special favor to me, that you remember them by lighting a candle that will burn for a day and a night and by saying the prayer for the dead—Kaddish. It is in the book.”

“You know I can’t read Hebrew.”

“When the time comes, open the book. You will be able to read it.”

“Uncle, please. Come with me. Aunt Greta . . .”

And then Uncle Otto gave me the ultimate family answer: “When you are more than three cheeses high, perhaps you will understand.” I was too young. I was too young to understand.

It was hopeless. “If you won’t run and hide, then at least turn on the gas for a while, light a match, and blow yourselves up.” I dumped the contents of the rucksack on their table and ran to the door.

“You will bring the blankets and the soap?”

“Yes. Tomorrow.” And without even saying good-bye to them, I was out the door and down the stairs, still clutching the flowers in my fist, Handel and the prayer book under my arm. I will never forgive myself for this, for not saying good-bye, for not staying to plead with them, for not telling them about the gas chambers and the ovens and the trains.

I had no stomach for facing Mother with the news, so although it was already eight o’clock and quite dark and cold, I, stupidly, took the train back to Hagen, hoping to get some advice and comfort from Tanya. Since our “talk” by the Geiger counters, we had been going together, more or less; that is, Tanya was not the kind of girl one took to the darkroom. I had virtually stopped seeing Monika—one cannot be totally impolite—my visits to the two girls in the village, about which Tanya never knew, were less frequent, and I would leave them, now, after the British had finished bombing, around midnight or so, and take the train back to Gartenfeld, which meant that I was not getting much sleep and was very tired.

I ran the three kilometers from the station to the Institute and through the park to Tanya’s building. It was dark, and the weather was unyieldingly Berlin—damp and cold. I raced up the stairs and knocked on her door. She had not yet let me come in her apartment, and there was to be no exception this night.

“Oh, Josef. I thought you’d gone home.” She opened the door a crack.

I bowed, slightly, and handed her Aunt Greta’s gladiolas. “Please, I need to talk to you.”

“Is something wrong?”

I nodded.

“Just a minute, I’ll get a sweater, and we can walk around the park and talk.”

“It’s getting quite chilly outside.”

“Then I’ll get a coat.”

As we walked, I told her exactly what had been said at my uncle’s. At one point, we sat on one of the stone benches along the winding drive. She, bundled in her warm coat, a wool scarf over her head, did not sit close to me. The bench was cold and hard. I was not dressed warmly enough. I am not certain what I expected from her.

“Your uncle is a fool!” she said. “One must fight! One must see the danger and use one’s strength and will.”

And then, as I sat there turning to stone, she told me a long story of how, when her mother received word she was to be taken, Tanya’s father put her on a train and had her ride around for days and days; then he sent her to a farm they knew in the country. At the same time, he sent Tanya to his friend—the Chief—at the Institute. The narration was filled with irrelevant detail—every train, every stop, the mechanics of contact—and full of sermons and vehemence. By the time she was through, I was frozen to the core.

“And that is why I am here at the Institute. I have no patience with people who will not fight! It is cold. I am going to my room.”

I walked her to her door. She unlocked it and stepped across the threshold.

“May I come inside?”

“You know I don’t permit that.”

Before she could shut the door in my face, I turned and ran down the stairs. I was a fool for looking for any comfort from her. She was a selfish, coldhearted bitch, as unlike Sheereen or Sonja Press as one could be, and any budding affection I might have had for her was killed that night.

I walked the three kilometers back to Hagen, took the train through Berlin, was held up for three hours because of the British—God bless them and help them smash the place to hell—arrived in Gartenfeld at three in the morning, and tiptoed into my parents’ bedroom. Dritt, who always slept on their bed at my father’s feet, raised his sleepy head and smiled at me. Good old Dritt. Mother slipped out of bed without waking Father.

In the kitchen, I told Mother about the summons and about Uncle and Aunt’s request for two blankets and some soap.

She, of course, was horribly upset by this, and began to wring her hands. “The blankets, yes, and soap. I will wake your father. He will give them money. They’ll need money if they are to make a journey.”

“Mutti, I think they should not go. They need to hide.”

“No, no,” she began.

“Listen to me. I have a friend at the Institute whose mother was sent such a letter, and her father put her mother on a train and had her ride around for days and days and then arranged to have her hidden at the farm of a friend. She is still alive! Surely Papa has family who will hide them.”

“I don’t know . . .” But she was hesitating!

“Mutti, they are shipping the Jews out in cattle cars, packed like sardines in a can, and they are—”

“Hush, Josef. Where do you hear such things?”

“Mutti, listen to me. I have not told you these things because I cannot bear to upset you. But it’s true. Mitzka Avilov told me. He saw these things and he heard about them from the Russian prisoners of war. Mutti, there are gas chambers. They use cyanide. They—”

Mother was on her feet. “I’ll talk with your father. He will want to give them some money. If they are to take a trip, they will need money. Are you hungry? There is a potato soup with good garden vegetables in the icebox.”

“Yes. I’ll eat something.” I was hopeful for the fifteen minutes Mother was gone that my parents might, this one time, come to their senses and face reality. While waiting for the water to boil and the soup to warm, I celebrated by helping myself to two liberal slices of bread and wurst. My disappointment, when Mother and Father remained true to form, was tenfold.

Mother returned with a small leather suitcase. “Here are the blankets, soap, some aspirin, money, and ration stamps. Can you think of anything else they might need? You said provisions for three days? There is bread and wurst. I’ll send that.”

“Mutti.”

She raised a hand to silence me. “Your father feels that they must obey the law. Your uncle was decorated for bravery during the First World War and will be treated fairly. Your father assumes they will be sent to Theresienstadt.”

“Mutti, Theresienstadt is not what you think.”

“Josef, you are too young to concern yourself with these things. I know how very tired you must be, but your father feels you must get back to your uncle’s with the suitcase as quickly as you can just in case they are asked to leave earlier. You must catch the first train—but by no means are you to draw attention to yourself by running. Do you understand?”

“Mutti. They will be transported in cattle cars and murdered—”

“Look what you have done! You have eaten the bread and wurst. Now I have no food to send them.”

The 4:09 arrived on the lowest-level track at Friedrich-strasse at 4:31; a five-minute climb to the upper level to catch the 4:38 for Ostkreuz. which arrived at Alexander-platz at 4:44; a ten-minute walk—I could have made it in six minutes running—to Grosse Frankfurter Strasse 47. At 4:54, I ran up the stairs. I was too late. They were gone. All that was left in their rooms were the dining table covered with a soiled white linen cloth with Grandmother’s initials monogrammed in white on the corner and, under the table, a small silver napkin ring with the initial O for Otto, and a Schiller, with the cover gone, stinking of mildew.

I folded the cloth neatly and placed it in the suitcase with the two blankets, the soap, and all, and put the silver napkin ring in my pocket. Then I leafed through the Schiller. It was an anthology of his plays. Uncle Otto had marked up the William Tell, and from what he underlined I realized that he had known, all along, and that I would never be able to forgive myself for not pleading with him, for not insisting, for not telling him what I knew.

Cast off, Ruodi! You will save me from death! Put me across.

Hurry, hurry, they are close on my heels already!

I am a dead man if they seize me.

What! I have a life to lose, too. Look there, how the water swells, how it seethes and whirls and stirs up all the depths. I would gladly like to rescue you, Baumgarten, but it is clearly impossible.

(Baumgarten still on his knees): Then I must fall into the hands of the enemy with the nearby shore of safety in sight! There it lies! I can reach it with my eyes. The sound of the voice can reach across. There is the boat which might carry me across and I must lie here, helpless, and despair.

Righteous heaven! When will the savior come to this land?

I should have refused to leave their apartment, should have forced them to listen, should have threatened to be there when the Gestapo came after them. I would never forgive myself.

The line the Chief parodied, “A Gestapo in the House saves one from a Caesarean section,” was from the first scene of the third act: Tell is in the courtyard in front of his house. Having just repaired the gate with his carpenter’s ax, he lays his tools aside and says to his wife, Hedwig:

Now I think the gate will hold a good long time. The ax at home often saves one from the carpenter.

William Tell had been my childhood hero. I pictured him striding about, saving the innocent, the crossbow on his back fastened across his breast by a colorful band. He saved Baumgarten, of course, by rowing him across the seething water, and then he saved the entire country with his crossbow and one apple.

When I returned to the Institute that same morning, I spread one of Uncle’s blankets on the floor under my worktable, covered myself with the other, and slept. Krupinsky and the others began the morning sorting and let me sleep. I awakened at noon, ate four bowls of polenta, and drank hot tea laced with vodka.

I did not even bother discussing the matter with Tatiana, nor did I tell her that I no longer cared for her, even though I knew that she felt we were officially going together. I began the retreat into a dead place within myself, and without comment I would listen to her daydream about our future: I was to be a famous mathematician and she a biologist; we would have two children, a boy named Josef and a girl named Tatiana. It was too late for me to become a mathematician, and I would never, never bring children into this hideous world. The more removed I felt and acted toward her, the more interested she became in me. François Daniel was right. The only way to win a woman like Tatiana was to seem to be disinterested. It is even more effective if the disinterest is genuine. Seems, Madam. Nay, it is; I know not “seems.” I did my work at the Institute efficiently, increased my visits to the darkroom with a grateful Monika, and visited more often the two girls from Chemistry who lived in the village of Hagen, staying until dawn, then returning to the Institute in the morning. I returned to the house in Gartenfeld only five times between September twenty-first, when Uncle Otto and Aunt Greta were taken, and October tenth, when they took my mother. So I saw her—Mother—only five times those nineteen days between, and I was so non-communicative that we hardly exchanged a word.

On Tuesday, October 10, 1944, at five in the afternoon, nearly two months after the liberation of Paris, we were finishing up in the lab when the Chief came to tell me that my parents had called. “Your parents called. Don’t go home tonight. Stay away. They are expecting visitors.”

I telephoned, but there was no answer. I left at once. The walk through the fields and forest and the little village of Hagen. The train to Potsdamer Platz. I watched passing trains for the face of my mother. The Americans had the habit of sending a few fighter bombers over, now and then, in the early evening, to stop the railways from running, and the trains held at the Potsdamer, which was underground, for almost three hours. It was dark when I arrived in Gartenfeld. I ran fast. I could not see and bumped myself on a corner mailbox, tearing my leg. Very painful. Bloody. A Jew dare not use a flashlight during a blackout and draw attention to himself. Remember Uncle Philip.

Father sat in his great chair before the fireplace in the small parlor on the first floor. There was no fire. He was wrapped in his overcoat. Dritt sat quietly on his lap.

“Where is my mother?”

“Did she receive a letter?”

“No. A neighbor called. Her husband was taken and she saw your mother’s name on the list.”

“Why didn’t you take her away?” I was shouting now. “How could you let them take my mother? Why didn’t you just shoot her and be done with it?”

“You are much too young to understand, and, furthermore, I owe you no explanation. But I will say this to you, Josef. Heretofore, the actions have been against households which are one hundred percent of your mother’s background; they have been predawn and secret. The S.S. has no desire to draw attention to what it is doing. But this present action, as I understand it, involves too many German households, is being carried out in daylight, and, therefore, it will draw attention to itself. Because of the outcry from the Germans involved, it will be abortive. If she were to try to evade arrest, they would get her on a criminal charge and there would be no recourse. Remember what happened to your Uncle Philip.”

“I despise you for bringing me into life.”

I went upstairs to Mother’s office to cleanse and bind my leg. The bleeding had stopped, but it would need several stitches. On her desk was her potato peeler. I put it in my pocket, then went up to my room and packed a suitcase.

He met me at the front door. “Your mother left a letter for you.”

I stuffed the letter in my pocket. On the way back to the train, I avoided the corner mailbox. The British were bombing again; the Wannsee Bahn waited at Potsdamer for many hours.

10 October 1944

My dear son Josef,

I have two wishes: that you study medicine and become the gifted surgeon you could be, and that you, as always, be honorable in your life and in your relationships with other human beings. There is no time to say more, but you know of my love for you.

Perhaps a moment more. Socrates has been no small comfort: “Those of us who think death is an evil are in error. For either death is a dreamless sleep—which is plainly good—or the soul migrates to another world. And what would not a man give if he might converse with Orpheus, Musaeus, and Hesiod and Homer.”

Ever,

Mutti

The second train arrived in Hagen shortly before dawn. I went to the apartment of Sonja Press and awakened her. She was alone. I thought she might comfort me in her bed, but she offered me only words—“Oh, my dear, I am so sorry!”—tea, vodka, and some of the Chief’s tobacco, which she rolled for me into a cigarette. I stood in the middle of her living room.

“Horrible,” I said.

“It should be good, Josef. It’s his new recipe, you know. He soaks the tobacco in prune juice and citric acid.”

“One might as well smoke stinking weeds. They are all crazy and they are all stupid. They think this stinking tobacco is good. It is not, I tell you. It is no damn good, and you know it.” I threw the burning cigarette to the floor.

She picked it up. “Sit.” Gently, she pushed me toward the couch. “Sit.” And she bent to untie my shoes. “Lie back, Josef, It’s almost morning.”

“Lie with me.”

“I can’t.”

“He does it with everybody.”

“You don’t understand.”

“Of course not. I am much too young to concern myself with such matters.”

“You don’t understand our Russian men. To them it is like drinking a glass of water. As important but also as unimportant. With the women it is different. For me there is no one else. Lie back. No one is too young now.”

I lay back. She removed my shoes, covered me with her shawl, pulled a chair beside the couch, and put her hand on my arm. It was dawn. And oh my good Lord said I knew you before I created you in the womb of your mother and I separated you before you were born by your mother. But I said, Oh, my good Lord, I am not fit because I am too young. But my good Lord said to me, Do not say I am too young, but you should go where I send you. And the Lord stretched his hand out and touched my mouth. . . .

“Josef, Josef, wake up.” The Chief was bending over me. He shook my arm. “Come now, Sonja has tea and cakes for us. We’ve half an hour to breakfast and go over to the lab.”

Ah, the wound in my leg was throbbing. And my head.

“Come! Sonja has prepared tea and cakes.”

But I was not hungry. I left without eating and hobbled across the park. As I entered the Institute, I heard Stanislas Rabin practicing on the Bechstein in the parlor on the first floor. I sat and listened. Over and over and over the same scales of the Chromatic Fantasia of Bach, expanding, intertwining, unfettered. He would reach the trill and return over and over and over to the beginning. One could run statistics on how many people would be using the train system in Berlin on a Tuesday morning at, say, six thirty, but if one wanted to choose one person only from the population of the city and determine whether or not this one person would be on the train at six thirty Tuesday morning, how could it be known? Or one knows that half the atoms of radioactive substances will have disintegrated in a certain length of time, but how can it be known which atom will go first? And how can it be said which follicle of the thousands in the ovary—for after all only one, rarely two or more—is destined to complete its development? Why that one? In my high school, the Calvinist ministers preached that those who reach grace are set apart before birth. Did they believe that Paul’s follicle was set aside in the ovary? But when he who had set me apart before I was born, and had called me through his grace. . . . And Jeremiah: And the word of the Lord happened to me and said, “I knew you before I created you in the womb of your mother.” . . . But I said, “Oh, Lord, Lord, I am not fit because I am too young.” But he said to me, “Do not say, ‘I am too young.’” Rabin began again. I had visitors. The Chief came in twice for five minutes, paced, walked out. Not a word. Then Tatiana stood before me.

“I am sorry about your mother.”

I shrugged and remained sitting.

“Why did you go to Sonja rather than to me?”

I shrugged again. She left. She helped now in the lab of Frau Doktor, the kind woman biologist, and still there was the problem of the clumsy mechanical handling of the larvae which I had noted my first day at the Institute. Each pair was taken from the slimy solution, put on a slide, and then operated upon. It came to me that it could be remedied by a turning disk, with space for several pairs, like that on a photograph, going around endlessly, listening to Rabin over and over and over, I pictured the disk to myself, planning so that I could explain it to the mechanic in the Physics Chapel in the park.

The Chief came again, this time with Professor Kreutzer, who stood before me and began to change his glasses. One feels most uncomfortable when he begins this. I stood.

He put on the black-rims, put away the rimless, and stared at me.

“Yes, Herr Professor?” I said finally.

“We are not getting any reproducible effects from the ultraviolet radiation of the flies. The variations are wild. See what you can come up with on this.”

“Yes, Herr Professor.”

He stood there looking at me. The Chief, of course, was pacing. Stanislas Rabin began again.

“Well!” barked Professor Kreutzer. “What are you waiting for?”

So I left the parlor and went up to the lab. Marlene and Krupinsky were there. He said, “Sorry to hear about your mother.”

“Will you take a look at my leg? I think it needs stitches.”

I lay down on a worktable, and he collected his paraphernalia.

“Listen, Josef, you need about five stitches, which means ten pricks with the needle. I can give you a local anesthetic, which means about four or six pricks, and, of course, means more chance of infection.”

“What kind of anesthetic?”

“Novocain.”

“Do you have any books on anesthesiology? I was wondering, if we changed from ether to something else, would the flies still ejaculate and lose their sperm when we anesthetize them?”

“Good Christ, Bernhardt, you won’t ejaculate if I give you Novocain, unless you have some strange perversion.”

“Do you have a book on anesthetics or not?”

“Not. Now don’t move!”

The Chief came to watch. Krupinsky washed the wound, sprinkled it with sulfa powder.

“We’ll try it without Novocain. If it hurts too much, give a yell, and I’ll deaden it, O.K.?”

He told the Chief I’d probably lost a bit of blood and that I should take it easy for the rest of the day. And he gave me a handful of vitamins and aspirin.

“I’m allergic to aspirin.”

He took the aspirin out of my hand. “Go home and rest.”

“Can you possibly find one for me?”

“What the hell are you talking about?”

“A book on anesthetic gases?”

“Christ, you never give up, do you?” He took two steps to the shelf where he kept his medical texts and grabbed a large volume. “Here!” He shoved it at me. “Pharmacology. That’s the best I can do. In Great Britain anesthesiology is an important specialty, but in Germany it is not. Here the gas is given by a sub-assistant or a nurse, and they mostly use ether because it is safest in the hands of the inexperienced.”

“Could you get a British text for me?”

“Now where in the hell am I supposed to lay my hands on something like that? Look, if it’s gases you are interested in, the Pharmacology should do it.”

I thumbed through the book:

ETHER: (C2H5)2O One of the safest and probably the most widely used of all the inhalation anesthetic agents. It is irritating to the respiratory tract. Its administration may be followed by increased secretions in the pharynx, trachea, and bronchi, by swallowing of ether-laden mucus, and by nausea and vomiting in the postoperative period.

I crossed the park to the Physics Chapel to find the mechanic. Together we dug through the junk looking for an old turntable to make the revolving-desk operating table for Frau Doktor. I was pleased to find an old record-cutting machine with a turntable ten times as heavy as an ordinary one. I had the mechanic cut it to a diameter of eighteen centimeters. It sat on an axle in which there was a friction bearing. I had him screw the whole thing onto a chunk of iron. Then we cut a Plexiglas disk, which fit with three prongs into the three slots we made in the turntable. We made twelve divided hollows in the desk—and twelve tiny removable cups to put over each hollow—in the same position as numbers on a clock, so the two larvae—donor and donee—could be placed side by side in the hollows. We cut grooves running to a reservoir in the center to be kept filled with saline solution so the larvae wouldn’t dry.

The day was gone. I hadn’t hooked up the motor yet, but I was dizzy from not eating, so I walked back to our building just as they were closing up.

Krupinsky said, “What are you doing here? I thought I told you to go home.”

“I don’t have a home.”

“Oh, come on, Josef. Why be self-destructive? Besides, your father—”

“Krupinsky, has it ever occurred to you to mind your own business?”

“No, I don’t think that it has. Did you take your vitamins?”

I nodded.

“What are you going to do? Where are you going to sleep? There are no empty apartments in the park or in Hagen.”

I shrugged. “I’m hungry.” My hands were shaking.

We made some tea and Krupinsky slaughtered a rabbit and asked Tatiana to put it in the autoclave. Then he and I drank tea with vodka and he left.

I stretched out on a worktable and let her watch the baking rabbit and warm some polenta. My throat was raw, my nose beginning to run. She brought a blanket and covered me.

“Thank you.”

“You’re welcome. Josef,” she said, “I want to know why you went to her instead of to me.”

The upper part of the spindle will be surrounded by a coil, an electromagnet. Parallel will be a large capacitor, and the battery can be switched on or off by a foot switch.

“Why don’t you answer me?”

She had tears on her face.

“I know you’re upset,” she said.

“I’m not upset. You’re upset.”

“I am sorry about your mother.”

I closed my eyes, on the verge of sleep.

“Why won’t you talk to me?” Her voice was shrill.

I opened my eyes. “I did not come to you, because it was too cold at four in the morning to sit with you on a cement bench in the park.”

“Where will you sleep tonight?”

I closed my eyes and drifted at once into sleep . . . The train, racing toward the end of a long, dark tunnel, collided with a brick wall. My body was cushioned by the bodies of others—Mitzka Avilov and Dieter Schmidt—and others whom I knew but could not recognize. The train was cut open with a carpenter’s ax, and I was lifted out and saved. I looked back down into it and saw the others, mashed, broken, and dismembered from the impact of my body, their skulls smashed and their brains spilling out into pools of their own gore.

Tatiana was shaking me. “Josef, Josef, wake up. You are having a nightmare.”

I sat up, confused and frightened. “Where am I?”

“You are in the Biology Lab. You were having a bad dream. Come, the rabbit is done. We can eat.”

We ate in silence, and I, instead of trying to sleep again, returned to the Physics Chapel and worked all night. By morning it was finished, and after the sorting of the flies, I took it in to Frau Doktor.

“The brake is very smooth-acting because of the capacitor, Frau Doktor, so because of the smoothness, the braking action doesn’t start immediately upon activating the foot switch, nor does it close, suddenly, upon disconnecting the battery with the foot switch. You must work with it until you have a sense of the rhythm of the time lag.”

We loaded the first twelve pairs of larvae onto the disk, and Tatiana and I watched while Frau Doktor lifted the cups and performed the transplants. It was efficient, and she was most pleased.

“You are talented in many ways.” She touched my hand. “What will you study when this war is over?”

Tatiana said, “Mathematics!”

“I’m not sure,” I said.

“What do you mean? We’ve always said you’d be a mathematician.”

Frau Doktor said to me, “Are you considering other things?”

“I haven’t really advanced at all in math for three or four years. It may be too late by the time this is over.”

Tatiana said, “Don’t be a fool. Newton quit school when he was fourteen and didn’t even go back to begin the study of mathematics until he was your age.”

“There is no one here who knows more about mathematics than I do, Tanya. There is no one here to teach me. There are no books. It is finished!” I turned to Frau Doktor. “I think it would be better to have two disks so that Tanya could prepare the second group of twelve while you worked on the first.”

Tatiana was angry. She left the room.

Frau Doktor embraced me and kissed my cheek. “My dear, if there is anything I can do for you, all you have to do is ask.” She looked something like my mother, but was quite a bit younger, thirty or so.

I returned to the Physics Chapel to make the second disk. Tatiana came at closing time, bringing me some bread, sausage, and tea.

“Thank you very much.”

“Where will you sleep tonight?”

I had a full-blown cold and my chest felt heavy. I was having trouble breathing.

“You’ve got to sleep somewhere.”

“There’s always the cement bench in the park.”

She began to weep.

“Why do you cry, for Lord’s sake?”

“You can’t sleep outside in this weather. What would people say? And you already have a cold.”

“Oh, my good Lord, Tanya, since when do you give a damn what happens to me? I’ll sleep under a table in the lab, or there are cots in the basement.”