![]()

WHILE WAITING FOR DOWNES TO RETURN FROM VALPARAISO, Porter decided to explore more of the islands. Before departing, he left a carefully concealed letter for Downes in a bottle buried at the head of Lieutenant Cowan’s grave and a duplicate at the foot of a finger-post that pointed out the grave. Porter left another note in a bottle suspended conspicuously at the finger-post for any British ships that might happen by, giving misleading information. It spoke of how desperate the Essex’s condition was. The crew was sick, it said, many had died; the frigate was in terrible condition, and the captured prizes had been either burned or given up to prisoners.

Although Porter was anxious for Downes to return, he did not intend to wait for him indefinitely. He planned to leave for the Marquesas Islands, come what may, no later than October 2. Porter was desperate for intelligence of British movements against him, and he was certain that Downes would provide it, but he thought they could just as well meet up in the Marquesas.

Porter planned to explore the Galapagos unencumbered by the slow-sailing Greenwich, Seringapatam, and New Zealand. He hid them in a small, obscure cove off Narborough Island while he went on a three-week cruise. He got underway from James Bay on August 20, and by August 22 he had the prizes in place. He put Lieutenant Gamble, commander of the Greenwich, in overall charge of the group, with strict orders to keep a sharp eye out for enemy ships from the highest point on the island, and not to attract attention. Fires were prohibited, and guns were to be silent. Porter also ordered Gamble not, under any circumstances, to let the ships fall into British hands. He was to destroy them if he had to and escape to the island in small boats. Of course, this was to be done only if there was no alternative. Porter expected Gamble to fight any attempt to take the ships, and only flee if absolutely necessary.

With all this in place, Porter left his charges on August 24. Fighting sudden shifts of wind and rapid currents, he traveled down the sound between Banks Bay and Elizabeth Bay, then attempted to weather the southern head of Albemarle. But a strong westward current stymied him. He was still there fighting the current on August 29, when finally, the wind shifted to the southward, and he was able to get around and reach Charles Island on August 31, where he dropped anchor.

During the next two weeks, he explored the waters around Charles, Chatham, and Hood islands. On September 14, he was back off the southern tip of Albermarle, where he intended to patrol for a few days. Around midnight, he hove to thirty miles off the island. At daybreak men at the main masthead saw a strange sail to the south. Porter grabbed a telescope and flew up the ratlines to have a look. As he focused, there was no doubt that she was a British whaler engaged in cutting up and processing a whale. She was to windward and drifting toward the Essex. Porter let her drift, and as she came toward him he did all he could to give the Essex the appearance of a merchantman. He struck down the fore and main royal yards and housed the masts. All the gun ports were shut tight, and he hoisted whalemen’s signals that he had obtained from the New Zealander. The ruse appeared to be working, until the stranger drew to within four miles and suddenly cut loose her whale carcass, put on sail, and made a desperate attempt to escape. Porter was right after her, and as soon as he was within gunshot range, he blasted away with eight cannon, forcing the whaler to strike her colors. She turned out to be the Sir Andrew Hammond, carrying twelve guns, although pierced for twenty. She had a crew of thirty-six, under Captain William Porter, who came aboard the Essex and swore that he was certain the Essex was a whaler until she was nearly upon him.

The Sir Andrew Hammond was loaded with fresh provisions and an abundance of strong Jamaica rum, which Porter distributed liberally to the Essex’s crew. The men had not had any since their July 4th celebration. They joyfully swilled all they were allowed. Porter had misjudged how potent the rum was, however, and before long, he had a ship full of drunks. He managed to keep matters under control, however, and passed it all off as harmless, except for one man who got completely out of control—James Rynard, a quartermaster who had been a clever troublemaker for some time.

Porter saw Rynard as a potential leader of a mutiny. When complaints were made, Rynard was habitually in the forefront. The Essex was filled with men whose terms of enlistment had expired, or were nearing that point, and Porter had given no evidence that he planned to return to America any time soon. It was conceivable that Rynard might use this to stir up discontent. Porter felt that he needed to make an example of him. To begin with, he confined Rynard in irons and then discharged him, having the purser make out his accounts. He then put him on the Seringapatam until they reached a place where he could be put on shore. Treating Rynard in this manner had the virtue of getting rid of a potential mutineer while giving pause to any like-minded hands.

Rynard did not go away so easily, however. He wrote a penitent letter to Porter begging him to overlook his past conduct and asking to be reinstated in the Essex. Porter refused, but Lieutenant Downes (after his return from Valparaiso) agreed to accept Rynard in the capacity of a seaman in Essex Junior, provided he behaved himself and gave no further cause for complaint. Rynard happily agreed, and the matter was settled.

PORTER EXPECTED DOWNES TO ARRIVE ANY DAY NOW; HE WAS anxious to hear the news he would bring. Lookouts were posted on the high ground north of the port on Narborough. A flagstaff was erected on the hill, and signals were arranged so that Essex Junior could see them from either Elizabeth Bay or Banks Bay. As anxious as Porter was to see Downes, however, he was still determined to stand out for the Marquesas no later than October 2.

While Porter waited, he brought the New Zealander and Sir Andrew Hammond into Port Rendezvous on Albermarle, where he could make repairs and otherwise put the ships in good order. Time passed slowly. Lookouts kept a sharp watch, and then, at noon on September 30 a ship appeared in Elizabeth Bay. A signal shot up to the top of the new flagpole. Porter felt certain that this was Essex Junior. His guess was soon confirmed, and by three in the afternoon she was anchored beside the Essex. When Downes came aboard with the prize masters and officers who had accompanied him to Valparaiso (including David Farragut), the crew gave a rousing cheer. Needless to say, Porter was overjoyed to see them, and more anxious than anyone to hear the news they brought.

Downes reported that he had sent the Policy and her load of sperm oil to the United States because of the low prices in Valparaiso. (Unfortunately, before Policy could reach America the British privateer Loire captured her.) So far as the Montezuma, Hector, and Catharine were concerned, Downes moored them in Valparaiso, waiting for either a better market or for Porter to decide where to send them. According to Downes, the Chileans had been as friendly and cooperative as they had been before, even though the country was embroiled in a deadly fight with Peru.

The rest of the news from Downes was far more exciting. President Madison had been reelected, and Downes confirmed what Porter had learned earlier, that the American navy, in the first seven months of the war, had indeed won a string of amazing victories (including the Essex’s over the Alert) in one-on-one battles with the British navy. As encouraging as this news was, Porter was even more interested in the intelligence provided by the American consul at Buenos Aires. The consul informed him that on July 5, 1813, the 36-gun British frigate Phoebe (Captain James Hillyar), accompanied by the 24-gun Cherub (Captain Thomas Tucker), the 26-gun Racoon (Captain William Black), and the 20-gun storeship Isaac Todd, had departed Rio de Janeiro with orders, it was rumored, to sail around Cape Horn and into the Pacific. Porter assumed they were coming after him, and nothing could have pleased him more.

In fact, in March 1813, the Admiralty, which had not yet heard of Porter’s rampage in the Pacific, had sent Hillyar and the Phoebe on a secret mission to what is now Oregon. There they were to capture Astoria, John Jacob Astor’s trading post at the mouth of the Columbia River. Hillyar’s orders were “to destroy, and if possible totally annihilate any settlements which the Americans may have formed on the Columbia River or on the neighboring Coasts.” The Canadian Northwest Company, operating from their base in Montreal, wanted to eliminate Astor’s settlement and set up their own base. The prime minister, Lord Liverpool, had much greater ambitions, however. He was laying the groundwork for a major expansion of British territory in the Pacific Northwest. He wanted to secure Britain’s claims to this vast area, claims that were originally established by the exploratory voyages of Cook and Vancouver, and by the remarkable overland explorations of Alexander Mackenzie when he reached the Pacific in 1793, ten years before Lewis and Clark. The large storeship Isaac Todd, which belonged to the Northwest Company, accompanied the Phoebe. She was to carry on trade with China after Hillyar seized Astor’s settlement.

Liverpool had chosen for the mission one of the Royal Navy’s premier captains. James Hillyar was an experienced officer with a distinguished fighting record. Born in 1769, he had served in the Royal Navy since the age of ten. He had been on HMS Chatham when she captured a French man-of-war off Boston in 1781. In 1783, when he was only fourteen years old, he was promoted to lieutenant. He remained in the navy, serving in various capacities until Britain’s wars with France began again in February 1793. He was then stationed in the Mediterranean for a long period, becoming a protégé of Britain’s most famous seaman, Admiral Horatio Nelson, who had notably high standards for the officers he favored. Hillyar drew Nelson’s attention during the latter’s famous defeat of the French fleet in Aboukir Bay near Alexandria in 1798, and on September 3, 1800, when Hillyar led boats from the Minotaur and Niger in a daring cutting out of two Spanish corvettes in the well-defended harbor of Barcelona. At the time, thirty-one-year old Commander Hillyar was first officer aboard the 32-gun Niger. He drew Nelson’s attention again in 1803, when he turned down an appointment that would have made him a post captain and guaranteed his future promotion to admiral—if he lived that long. Promotions from post captain to admiral were based strictly on seniority. Hillyar was the sole support of his mother and sisters, and the promotion would have meant an interruption in his pay for an uncertain period of time. After hearing what Hillyar did, Nelson, as a mark of his favor, invited him to dinner, and on January 20, 1804 he wrote to the First Lord of the Admiralty, John Jervis, the 1st Earl of St. Vincent, that “Captain Hillyar is most deserving of all your Lordship can do for him.”

Appointed to the Phoebe in 1809, Hillyar assisted in the successful British invasion of the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius in December 1810. France had held Mauritius since 1715, calling it Île de France. Success, in fact, had marked Hillyar’s entire career. He arrived in Rio on June 10, 1813, much annoyed at the slow sailing of the cumbersome Isaac Todd. Admiral Dixon already knew the Phoebe was coming. The merchant brig John had spoken the Phoebe during her passage to Rio and reported to Dixon that she was en route. Dixon welcomed this news since he was about to dispatch one of his scarce warships, the Cherub, to guard a convoy of merchantmen sailing to England.

At the last minute, Dixon held the Cherub back and waited for the arrival of the Phoebe. Embarrassed by Porter’s unopposed attacks, Dixon thought he could now send the Cherub and the Racoon to accompany the Phoebe and hunt down the Essex. Until this point, he had been utterly frustrated at not being able to go after her—and particularly so since the Admiralty on February 12, 1813, had sent him a message, which he received on April 29, to send at least one warship into the eastern Pacific to protect British commerce, and particularly the whale fishery. At the time, Whitehall did not know about the rampaging Essex. Instead the Admiralty was focused on the general collapse of Spanish power in the eastern Pacific and the resultant threat to British ships, as well as the opportunity to expand British interests.

When their Lordships found out about the Essex, they did not understand why Dixon had not sent the Cherub and Racoon after the American frigate long before now. Dixon for his part felt that he did not have enough warships to both go after Porter and continue to protect Britain’s burgeoning trade along the east coast of South America.

Needless to say, Dixon was very happy to see Hillyar and the Phoebe. He was not privy to Hillyar’s secret orders, directing him to seize the American trading post at Astoria. Dixon would have to wait and see what Hillyar’s orders were before making a final decision about sending him after the Essex. And Hillyar for his part would have to decide whether or not to show his orders to Dixon, since they were so sensitive. At length, he had to disclose them, because stopping the Essex had become such a high priority.

Dixon did not know Porter’s exact whereabouts. He did know that Porter had been to Valparaiso and had left, and that he had seized at least one Peruvian vessel, but he did not know where Porter had gone after that. He was told that the Essex might have headed west with the intent of sailing into the Indian Ocean and joining other American warships like the Constitution and the Hornet. He was also told that the Essex might be sailing back around the Horn, touch at the mouth of the River Plate, and then go home. The Galapagos were also a possibility. Dixon thought it was possible, even likely, that Porter would continue in the eastern Pacific for a time, and be back in Valparaiso sooner or later for supplies and recreation. Neither Dixon nor any of his captains thought the Essex would make for the Marquesas Islands.

When Hillyar arrived in Rio on June 10, widespread discontent aboard the Isaac Todd was reported to Dixon. Hillyar had had to punish some of her crew during the voyage. Immediately on entering port, two mates had left her and seven seamen deserted, stealing one of her boats and disappearing during a dark night. Dixon found that the ship was badly stowed, had heavy masts and rigging, and far too many guns on her deck. Many crewmembers, including most of her officers, thought the Isaac Todd was not safe to sail in, especially around the Horn. None of this fazed Dixon; he got right to work fixing her, and had her repaired and ready to go in short order.

Nearly a month went by, however, before Hillyar and the Phoebe departed Rio on July 6, accompanied by the Cherub, Racoon, and Isaac Todd. Although aware of the importance of destroying the Essex, Hillyar intended to follow his secret orders and capture Astor’s settlement on the Columbia River first. The passage around Cape Horn was predictably difficult. The struggling Isaac Todd failed to keep up and got separated from the others. Hillyar thought she had foundered. Nonetheless, after doubling the Horn, he waited a decent amount of time for her, and when she failed to appear, he moved on, setting a course north for the Columbia River. When he was at latitude 4° 33’ south and longitude 82° 20’ west, he received news from a passing British vessel that the Essex had captured the Isaac Todd, which, of course, was not true, but he decided at that point to depart from his orders and send the Racoon to the Columbia River alone, while he took the Phoebe and the Cherub and went after the Essex. He was supported in this decision by John McDonald, the representative of the Northwest Company on the Phoebe. Hillyar did not anticipate that it would take long to find the Essex. (The Isaac Todd in fact had not foundered, as Hillyar thought, or been captured. It had doubled the Horn and eventually made it all the way to the mouth of the Columbia River, where, after extensive repairs, she began trading Indian furs with China for the Northwest Company.)

Hillyar’s expectations about finding the Essex quickly turned out to be unfounded. His search for her went on week after anxious week along the coasts of Chile and Peru with no result. Porter had seemingly vanished. Hillyar was frustrated, but no more so than Admiral Dixon and their Lordships at the Admiralty who were hearing alarming reports of all the prizes Porter was taking, and his devastating impact on the British whale fishery. Wherever the Essex was, however, Hillyar was confident that she would eventually return to Valparaiso.

Meanwhile, Captain Black sailed the Racoon to the Columbia River, arriving on November 30, 1813. There he found, to his great surprise, that the Northwest Company had already taken possession of Astoria, had renamed the fort Fort George, and now flew the British flag over the outpost. No Americans were there. As far as he could tell, their party was completely broken up; they had no settlement on the river or on the coast. He reported that while his provisions lasted, he would endeavor to find what remained of their party and destroy them.

The Pacific Northwest had been of great interest to Britain since the last part of the eighteenth century when Captain Cook had visited there. Spain had a strong interest as well, dating back to the sixteenth century, and so did Russia. The European rivalry nearly resulted in a war between Britain and Spain in 1789 over competing claims to Nootka Island and what became known as Vancouver Island. The United States had a strong interest as well. In May 1792 an American captain, Robert Gray, had been the first outsider to venture into the Columbia River in his ship Columbia. At the time, the famous British explorer George Vancouver was in the area, and he and Gray had met and talked about the difficulty of exploring the river. Vancouver decided that it was impossible because of the tricky entrance, but Gray attempted it and succeeded, thus establishing an American claim to the river, the country surrounding it, and, indeed, the entire Northwest. America’s interest was heightened significantly after Jefferson sent Lewis and Clark on their famous expedition. Neither the European countries nor the United States thought the Native Americans who abounded in the area would be an obstacle to expansion.

John Jacob Astor, the fur trader, became interested in establishing a trading post at the mouth of the Columbia in 1811–1812. He wanted to trade the bountiful furs of the American Indians in China, and he succeeded in establishing his Pacific Fur Company at the mouth of the river, naming the settlement Astoria. It was this settlement that Captain William Black was sent to destroy. Before he arrived, however, the Pacific Fur Company heard that the British were coming to seize it and decided to sell to the Northwest Company before the Royal Navy arrived and simply took it.

PORTER LEFT THE GALAPAGOS ISLANDS, AS PLANNED, ON October 2, 1813. His performance during the time he was there and that of Lieutenant Downes and the rest of the Essex men had been spectacular. Their seamanship had been continuously tested. They had no reliable navigation charts, and the prevalence of fog, strong, tricky currents, and erratic winds made sailing at all times dangerous. That they survived with no major mishaps was a testament to their luck, certainly, but also to their extraordinary courage and skill.

Porter enumerated in his journal all he had accomplished:

We have completely broken up [the British] whale fishery off the coast of Chile and Peru. . . . we have deprived the enemy of property to the amount of two and a half millions of dollars, and of the services of 360 seamen. . . . We have effectually prevented them from doing any injury to our own whale ships. . . . The expense of employing the frigate Phoebe, the sloops of war Racoon and Cherub [also had to be taken into account].

Porter estimated that the cost of sending three warships after the Essex was $250,000. He claimed that by adding the actual captures he made to the value of the American whale ships who were not captured because of his presence, to the cost of sending warships after the Essex, less the expenses of the Essex for a year ($80,000), his activities cost the British $5,170,000. Whether this fanciful figure bore any relation to reality was of little importance. What mattered was that, without a doubt, Porter had had a significant impact on Britain’s whale fishery, as well as on America’s. And he did it at a negligible cost to his government.

As much as Porter had accomplished, however, and as fine as his ship and crew had performed, they needed a secure place to refresh. The Essex, having been at sea almost continuously for eleven months, required a major overhaul, and her crew, although still in remarkably good health, needed time ashore. The Marquesas Islands were the perfect place for both.

PORTER LEFT THE GALAPAGOS IN THE NICK OF TIME. CAPTAIN Hillyar arrived there three weeks later, on October 23, with the Phoebe and the Cherub, and stayed for weeks. To begin with, he searched everywhere among the islands for the Essex. It took him several weeks, and when he could not find her, he remained for an additional time, hoping she would return. Porter had no intention of going back, however, and Hillyar remained frustrated and anxious. He knew how badly the Admiralty wanted the Essex destroyed. When he finally gave up and left the islands, he returned to the South American coast and began again a thorough search there, which consumed even more time. He must have wondered if he would ever find the Essex. Porter may have simply gone home, either sailing around Cape Horn or traveling west across the Pacific to the Indian Ocean and around the Cape of Good Hope. It’s unlikely that Hillyar ever considered that Porter might be seeking him out as much as he was seeking the Essex. The idea would have struck Hillyar as preposterous.

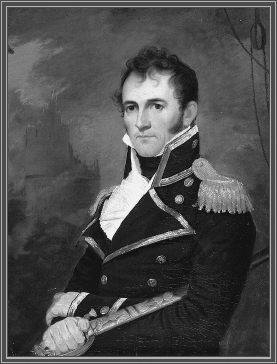

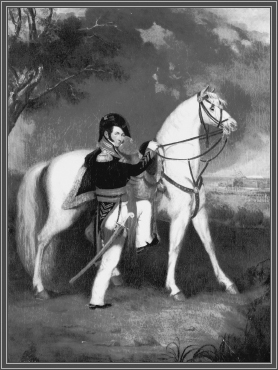

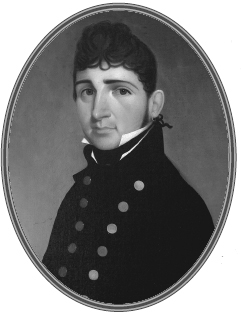

Captain David Porter

(COURTESY OF THE NAVAL ACADEMY MUSEUM)

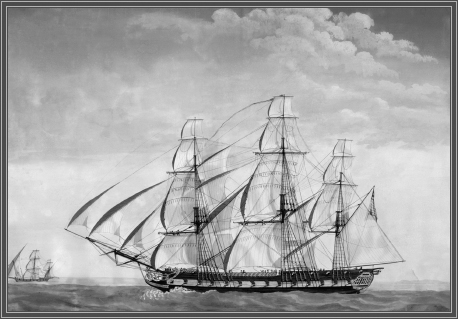

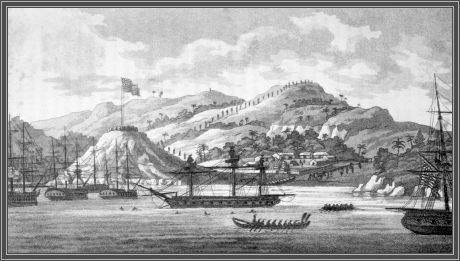

The USS Essex

(COURTESY OF THE PEABODY ESSEX MUSEUM)

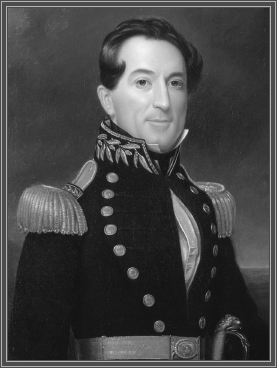

David Glasgow Farragut at age thirty-eight

(COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY)

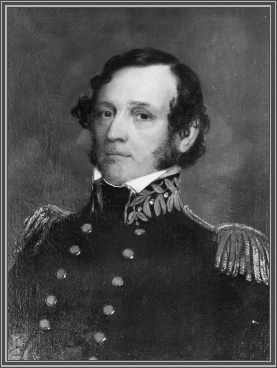

Lieutenant John Downes

(COURTESY OF THE NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS)

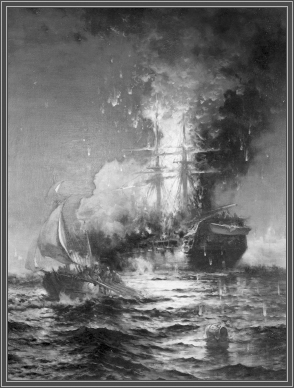

The burning of the Philadelphia

(COURTESY OF THE NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS)

Commodore William Bainbridge

(COURTESY OF THE NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS)

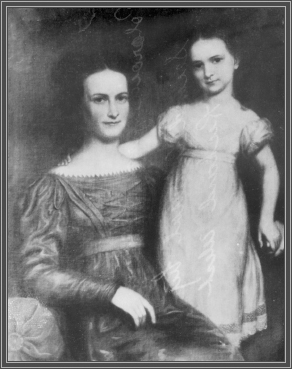

Evelina Anderson Porter and her daughter

(COURTESY OF THE NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS)

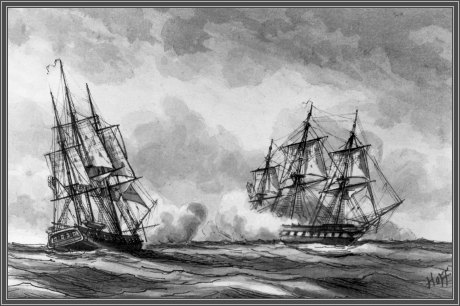

The Essex capturing the Alert

(COURTESY OF THE NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS)

Thomas Truxtun

(COURTESY OF THE NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS)

Marine Lt. John M. Gamble, painted later in life when he was a Lieutenant Colonel

(COURTESY OF THE NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS)

Joel R. Poinsett

(COURTESY OF THE NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS)

Commodore Edward Preble

(COURTESY OF THE NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS)

John G. Cowell

(COURTESY OF THE MARBLEHEAD, MASSACHUSETTS, HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

Captain Porter’s drawing of the Essex and her prizes

(COURTESY OF THE NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS)

Captain Porter’s drawing of a woman on Nuku Hiva

(COURTESY OF THE NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS)

Captain Porter’s drawing of Mouina, Chief Warrior of the Taiohae

(COURTESY OF THE NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS)

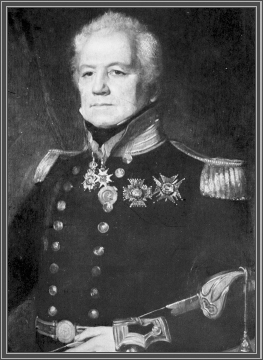

Captain James Hillyar

(COURTESY OF THE NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS)

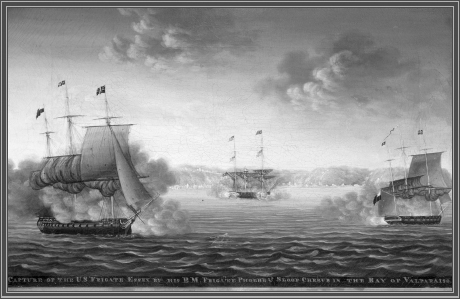

Capture of USS Essex by HMS Phoebe and HMS Cherub

(COURTESY OF THE PEABODY ESSEX MUSEUM)