OPENING THE DOOR TO MASS IMMIGRATION FROM THE COMMONWEALTH

The 1948 British Nationality Act transformed the racial make-up of Britain. At the time that the legislation passed into law, non-white faces were a rare sight in all but a few parts of the country. Even the immigrant communities, new or old, were overwhelmingly European. By holding wide open Britain’s door of entry to anyone born anywhere within the borders of her empire and Commonwealth, the 1948 Act forever changed the national composition and set the United Kingdom on a path towards a multiracial, multicultural future.

It may have seemed counter-intuitive for Clement Attlee’s government to make so affirmative an expression of faith in the unity of empire only months after India and Pakistan had been granted independence from it. The loss of the ‘jewel in the crown’ was indeed the beginning of a process of decolonization that would be completed in 1997 with the handover of Hong Kong to China. Nonetheless, in the post-war years there was widespread faith in the future of the British Commonwealth (of which India and Pakistan became members). This was not just a reflexive scramble for a face-saving idea to conceal the reality of a world power in decline. The many peoples of the empire, of all faiths and colours, who had volunteered to fight in the common cause between 1939 and 1945 demanded a retrospective expression of gratitude from – depending on their political viewpoint – their mother country or colonial master.

From the British Nationality Act, 1948

1.—(1) Every person who under this Act is a citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies or who under any enactment for the time being in force in any country mentioned in subsection (3) of this section is a citizen of that country shall by virtue of that citizenship have the status of a British subject.

(2) Any person having the status aforesaid may be known either as a British subject or as a Commonwealth citizen; and accordingly in this Act and in any other enactment or instrument whatever, whether passed or made before or after the commencement of this Act, the expression “British subject” and the expression “Commonwealth citizen” shall have the same meaning.

(3) The following are the countries hereinbefore referred to, that is to say, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, Newfoundland, India, Pakistan, Southern Rhodesia and Ceylon.

Directly prompted by changes in Canada’s citizenship laws, the 1948 Act primarily had in mind the right of entry of those of British descent from the ‘white dominions’ of Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. Strictly speaking, it reaffirmed an old policy dating from the start of a previous call to imperial arms. The 1914 British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act gave British citizenship to ‘any person born within His Majesty’s dominions and allegiances’. As a result, 400 million subjects of the British Empire had effectively been granted the right to settle on a small island off the European continent, but very few of them had done so. Opportunities for migrants usually appeared better for those going to the ‘white dominions’ than to Britain and the cost of long-distance travel was beyond the means of most Indians, Africans or inhabitants of the Caribbean. Although the history of black settlers in Britain went back at least to the sixteenth century (when Queen Elizabeth I complained there were too many of them) and they had long formed strong communities in port cities like Liverpool and Cardiff by the 1930s, the non-white population of Britain numbered only a few thousand.

The 1948 British Nationality Act came at a time when the cost of travel was falling. The result was immigration from the ‘New Commonwealth’ (essentially, the Indian subcontinent, Africa and the West Indies) on a scale that the framers of the legislation had never imagined. The influx began when an old troopship, the Empire Windrush, docked at Tilbury on 22 June 1948 with 492 migrants travelling from Jamaica. Immigrants from the Caribbean had traditionally gone to the United States, but in 1952 the US government restricted their entry. Britain became their destination instead. Census returns pointed to a rise in Britain’s ‘coloured’ population from 74,500 in 1951 to 336,000 in 1961. Of these, by far the largest proportion (171,800) had come from the West Indies, while 81,400 were from India, 24,900 from Pakistan and 19,800 from West Africa.

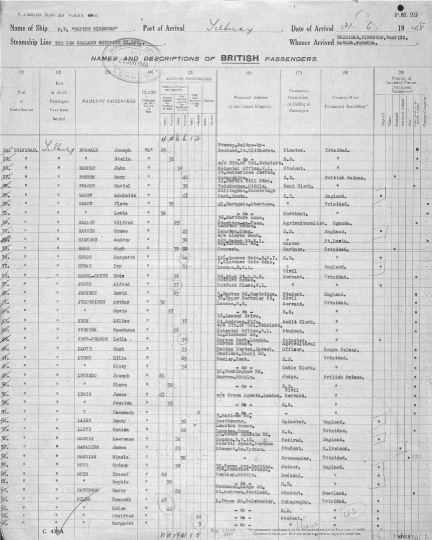

The Empire Windrush’s passenger list, 21 June 1948.

The immigrants’ contribution became particularly evident in the transport sector and the health service. Subsequent generations, particularly of Asian descent, brought an entrepreneurial spirit and entered the professions. Yet the argument raged over whether many of them were doing important, otherwise unfillable, jobs or were changing the nature of the country in a way that left many native-born Britons uncomfortable. During the 1950s, successive Conservative administrations considered plans to reduce the inflow but did not implement them, in part because of a reluctance to be seen to discriminate between black migrants from the New Commonwealth and those of British descent from the ‘white dominions’, whom they still regarded as ‘kith and kin’.

The first restrictions came with the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act, which stemmed the flow by insisting on the possession of employment vouchers. Having opposed restrictions while in opposition, Harold Wilson’s Labour government after 1964 tightly controlled the number of vouchers available. However, the government tried to make life more tolerable for those who had already arrived by passing the 1965 Race Relations Act, which made racial discrimination illegal.

The first wave of arrivals were overwhelmingly young males, mostly unskilled or semi-skilled, coming in search of work. Many repatriated some of their earnings back home. Over time, their families came out to join them in Britain, a major factor in the rate of entry remaining above 50,000 a year after the 1962 Act. Faced with an influx from East Africa, in 1968 legislation finally discriminated against those who had not been born in Britain or, failing that, had a parent or grandparent born there.

The heated debate focused on only one aspect of migration policy. In fact, net emigration from Britain exceeded net immigration every year from 1946 to 1979. This was overwhelmingly the result of Britons starting new lives in the sun rather than recent arrivals returning back to the warmer climes they had left behind. Southern Rhodesia (modern Zimbabwe) was a popular destination in the 1950s; during the 1960s, British emigration to Australia and New Zealand ran at between 80,000 and 100,000 a year.

Another aspect of policy that caused a significant migration shift within the British Isles concerned the favourable status accorded the Southern Irish. In 1947, Ireland announced that it was formally becoming a republic and leaving the Commonwealth. Rather than draw the perhaps natural conclusion that the link with Dublin was severed, the 1948 British Nationality Act guaranteed Irish citizens the rights to reside and to vote in Britain. Many took up the offer. In this way, non-members of the Commonwealth ended up enjoying easier entry than Commonwealth members. This process was completed when Britain became part of the free movement of peoples within the European Community.