THE SECRET DOCUMENT BEHIND THE SEUZ CRISIS

The Sèvres Protocol was top secret. It engineered the Suez Crisis, one of the most calamitous – and shameful – episodes in British foreign policy. Having destroyed his copy of the incriminating document, Anthony Eden, the prime minister, always denied it had ever existed. Unfortunately for his reputation, the Israeli government kept its copy.

In post-war strategy, successive Labour and Conservative administrations regarded the Middle East as being of vital national importance. The region was host to major British economic investments (especially oil) as well as to British naval and air bases from which to counter the Soviet threat. Clement Attlee’s Cabinet considered, before deciding not to use, military action against Iran when it nationalized the Anglo-Iranian Oil (subsequently BP) refinery at Abadan in 1951. However, two years later, the British and United States governments ensured the restoration of their oil concessions by providing backing for a coup in Tehran that overthrew the Iranian leader, Mohammad Mosaddeq.

Meanwhile, in 1952 a military coup in Cairo had removed Britain’s client rulers in Egypt and set the path for Gamal Abdel Nasser, an Arab nationalist, to come to power. Although Britain negotiated an orderly withdrawal from its Egyptian bases, it considered as sacrosanct the maintenance of the Suez Canal as an international shipping lane and conduit for Europe’s oil supplies. When, on 26 July 1956, Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, the new British prime minister, Anthony Eden, feared the worst.

Eden’s foreign secretary, Selwyn Lloyd, was dispatched to the United Nations in New York to try to broker a settlement. On 14 October, Eden was visited at Chequers, the prime ministerial weekend home, by General Maurice Challe, the deputy chief of staff of the French armed forces, and the French minister for social affairs (deputizing for the foreign minister), Albert Gazier, who put to him an extraordinary proposal. They suggested that if Israel could be persuaded to attack Egypt across the Sinai peninsula this would provide a convenient pretext for the British and French to land peacekeeping forces along the Suez Canal zone. Having secured it, they could from there help bring down Nasser’s regime.

THE RETREAT FROM EMPIRE: BRITAIN’S FORMER COLONIES GAIN THEIR INDEPENDENCE

1947 India gains independence (and is partitioned, creating also West and East Pakistan).

1948 Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and Burma gain independence.

1949 The Republic of Ireland leaves the Commonwealth.

1954 British troops vacate Egypt and Sudan gains independence.

1957 The Gold Coast (Ghana) gains independence, as does the Federation of Malaya (Malaysia).

1960 Cyprus, British Somaliland and Nigeria gain independence.

1961 Sierra Leone, British Cameroon and Tanganyika gain independence. South Africa, under National Party rule, leaves the Commonwealth.

1962 Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Western Samoa and Uganda gain independence.

1963 Kenya and Zanzibar gain independence, the latter to merge with Tanganyika to form Tanzania.

1964 Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), Nyasaland (Malawi) and Malta gain independence.

1965 Southern Rhodesia makes its unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) from British rule, to avoid black-majority rule. The Gambia gains independence.

1966 Barbados, Lesotho and Botswana gain independence.

1967 Aden (South Yemen) gains independence.

1968 Mauritius and Swaziland gain independence.

1970 Fiji and Tonga gain independence.

1971 Bahrain and Qatar gain independence.

1973 The Bahamas gain independence.

1974 Grenada gains independence.

1976 The Seychelles gain independence.

1978 Dominica gains independence.

1979 The Gilbert Islands (Kiribati) gain independence.

1980 Zimbabwe (formerly Southern Rhodesia) gains independence after a prolonged liberation struggle.

1981 Belize gains independence.

1984 Brunei gains independence.

1996 South Africa under Nelson Mandela rejoins the Commonwealth.

1997 Hong Kong is reunited with China following the expiration of its lease to Britain.

Regrettably, Eden thought this was a sound idea. Two days later he travelled with Lloyd to France for talks at the Palais Matignon with Guy Mollet, the French prime minister and his foreign minister, Christian Pineau. Lloyd did not like the plan but lacked the courage to stand up to Eden, whose reputation in foreign policy was high (he had three times been foreign secretary, in 1935–8, 1940–45 and 1951–5). Eden became obsessed with the notion that Nasser was another Hitler whose ambitions it would be calamitous to appease. Fearful of Nasser’s support for Algerian nationalists, the French had as much – indeed more – reason than the British to want to see the regional troublemaker toppled. Crucially, Israel had to be brought into the conspiracy too.

The vital negotiations were conducted, in tight secrecy, between 22 and 24 October, at a suitable location – on the Rue Emanuel Girot in the Paris suburb of Sèvres in an elegant villa that had been a hideout for the French Resistance during the war. The talks began with the French delegation, led by Mollet and Pineau, trying to persuade the reluctant Israelis to do their bidding. The Israeli team, led by their prime minister and defence minister, David Ben-Gurion, included Moshe Dayan and Shimon Peres. They were then joined by the British, looking distinctly uncomfortable, in the guise of Selwyn Lloyd and his private secretary, Donald Logan.

Eden preferred not to attend in person and his aloofness was understandable. After all, it was a covert meeting of those conceiving an international conspiracy. Lloyd was ill at ease and it was only after his departure that relations between the French and Israelis improved on the second day. That night, back in London, Lloyd and Eden discussed progress with Pineau. Brushing aside moral and practical complaints, Eden remained enthusiastic. All was set for the third and final day’s negotiations at Sèvres. With Lloyd unable to attend, Britain was represented there by Donald Logan and Patrick Dean, an assistant under-secretary of state at the Foreign Office.

The Israelis were finally persuaded, seeing the scheme as a chance to be rid of Nasser, a potentially implacable enemy, whilst cementing better relations with the French and British. It was agreed that Israel would initiate the crisis by invading the Sinai peninsula on 29 October. Feigning shock, the British and French would issue separate appeals for both sides to disengage and then land their own forces in the canal zone as a buffer between the rivals, supposedly destabilizing Egypt and thereby threatening Nasser’s position. Much as the British would have preferred to keep the details off the record, they felt it might look suspicious if they refused Ben-Gurion’s request that a summary of what had been agreed should be drawn up and signed.

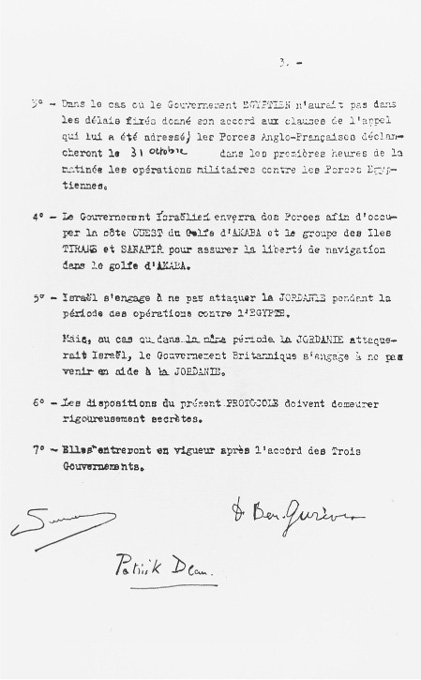

A surviving copy of the incriminating document that Anthony Eden denied existed. The Sèvres Protocol was hurriedly typed up in French and signed by the French foreign minister, Christian Pineau, the British under-secretary of state, Patrick Dean, and the Israeli prime minister, David Ben-Gurion.

The results of the conversations which took place at Sèvres from 22–24 October 1956 between the representatives of the Governments of the United Kingdom, the State of Israel and of France are the following:

1. The Israeli forces launch in the evening of 29 October 1956 a large scale attack on the Egyptian forces with the aim of reaching the Canal Zone the following day.

2. On being apprised of these events, the British and French Governments during the day of 30 October 1956 respectively and simultaneously make two appeals to the Egyptian Government and the Israeli Government on the following lines:

A. To the Egyptian Government

a) halt all acts of war.

b) withdraw all its troops ten miles from the Canal.

c) accept temporary occupation of key positions on the Canal by the Anglo-French forces to guarantee freedom of passage through the Canal by vessels of all nations until a final settlement.

B. To the Israeli Government

a) halt all acts of war.

b) withdraw all its troops ten miles to the east of the Canal.

In addition, the Israeli Government will be notified that the French and British Governments have demanded of the Egyptian Government to accept temporary occupation of key positions along the Canal by Anglo-French forces. It is agreed that if one of the Governments refused, or did not give its consent, within twelve hours the Anglo-French forces would intervene with the means necessary to ensure that their demands are accepted.

C. The representatives of the three Governments agree that the Israeli Government will not be required to meet the conditions in the appeal addressed to it, in the event that the Egyptian Government does not accept those in the appeal addressed to it for their part.

3. In the event that the Egyptian Government should fail to agree within the stipulated time to the conditions of the appeal addressed to it, the Anglo-French forces will launch military operations against the Egyptian forces in the early hours of the morning of 31 October.

4. The Israeli Government will send forces to occupy the western shore of the Gulf of Aqaba and the group of islands Tirane and Sanafir to ensure freedom of navigation in the Gulf of Aqaba.

5. Israel undertakes not to attack Jordan during the period of operations against Egypt. But in the event that during the same period Jordan should attack Israel, the British Government undertakes not to come to the aid of Jordan.

6. The arrangements of the present protocol must remain strictly secret.

7. They will enter into force after the agreement of the three Governments.

(signed)

CHRISTIAN PINEAU PATRICK DEAN DAVID BEN-GURION

The resulting protocol was hurriedly typed up in French on a portable typewriter – seemingly without sufficient time to correct minor typing errors and its irregular layout. Three copies were made, one for each of the participating delegations. Pineau signed for the French and Ben-Gurion for the Israelis. Dean initialled each page on behalf of Britain and signed at the end. Stilted congratulations were exchanged over a glass of champagne. The party became more amicable after the British left, when the French and Israelis felt able to toast another consequence – separate and unknown to the British – of their collaboration: namely, French assistance in turning Israel into a nuclear power.

Back in Britain, Eden endorsed Dean’s actions whilst being furious that a formal record had been kept. He had the British copy destroyed and tried – in vain – to get the French and Israelis to do likewise (although the French copy was subsequently mislaid).

The Israeli attack went according to plan; British and French troops landed without serious losses, but the plotters had failed to take sufficient account of a crucial factor: the hostility of the United States. Transatlantic relations turned sour. Oil sanctions were threatened. Critically, there was a run on the pound. Lacking the reserves to support the plummeting value of the currency, Harold Macmillan, the chancellor of the exchequer, performed a dramatic U-turn, arguing in Cabinet for the suspension of the military operation as the only means of securing the vital American financial support that was currently being withheld. Reluctantly, Eden felt compelled to bow to the pressure of the money markets. A ceasefire was arranged for 5 p.m. on 6 November and on 2 December the government formally announced that all British forces were being immediately withdrawn from Egypt.

For Britain it was an unqualified humiliation. The episode appeared to show that this once great power was so economically weak that it could no longer operate a foreign policy independent of American support. The domestic political repercussions were also enormous. The Labour Party found a strong and united voice in opposing the adventure. Middle-class liberals felt alienated by the actions of a Conservative leader they had previously admired. Still suffering from the severe stress that undermined his judgment during the crisis, Eden fell genuinely ill from a bungled gall-bladder operation and resigned in January 1957.

The humbling of Britain’s global pretensions was not the least of it. Moscow had previously decided not to intervene against the reformist government in Hungary, but changed its mind when the Suez Crisis provided the necessary distraction. While the world was watching events on the Sinai peninsula, Soviet soldiers and tanks were sent in to crush Budapest’s assertion of independence, killing 20,000 Hungarians in the process. The cracks in the Iron Curtain were filled up again with devastating consequences for the world.

Both in Britain and abroad there was widespread suspicion from the first that the Suez Crisis was the consequence of collusion between the British, French and Israelis. Eden had mentioned in a Cabinet meeting of 23 October ‘secret conversations which had been held in Paris with representatives of the Israeli Government’ about which none of his colleagues chose to challenge him. Only the minister of state at the Foreign Office, Anthony Nutting, resigned. Eden then lied to the House of Commons on 20 December when he stated: ‘to say it quite bluntly to the House there was not foreknowledge that Israel would attack Egypt – there was not’, a pretence he maintained subsequently.

Nutting was the first official to publicly admit – in his autobiography of 1967 – that there had been collusion at Sèvres. The French and Israeli participants followed suit. It is only because the Israelis refused Eden’s request that they burn the secret protocol that we have unanswerable proof of the full extent of the Franco-British conspiracy.