ESTABLISHING THE BOUNDARY BETWEEN ANGLO-SAXON AND VIKING-OCUPIED ENGLAND

The survival of Christian Britain was as fragile as the parchments upon which the monks of Jarrow and Lindisfarne chronicled and commemorated it. During the eighth century, fresh waves of invasion by a new pagan foe, the Vikings, threatened to drive it back to the periphery.

Sailing from Scandinavia, the Norsemen and Danish warriors reached far-flung corners of the island. Wales suffered least, beyond some incursions along the coast. In Scotland, however, the Vikings seized the northern and western isles, sacking the monastery at Iona in the process. England came under intense attack, with the looting of Lindisfarne just a foretaste. In 867 the previously dominant kingdom of Northumbria fell to the invader. The Midlands kingdom of Mercia capitulated the following year. By 871 every kingdom had been overwhelmed – with the exception of Wessex. If it fell, Anglo-Saxon England was lost.

This silver penny was minted during the rule of King Alfred over Wessex (871–99). It depicts Alfred on the obverse while on the reverse a cross and a monogram of Londonia acknowledge the absorption of London into his realm.

The fate of Wessex rested with its new king, the twenty-two-year-old Alfred. He had become battle-hardened the previous year, helping his brother to see off one Viking assault at Ashdown in Berkshire, only to lose successive encounters thereafter. Further battles and parleys followed, with the Vikings penetrating deep into Wessex. They held Reading; then even Exeter fell to them. In January 878 their warlord, Guthrum, launched a surprise onslaught, seizing Chippenham and almost capturing Alfred.

Slipping from his pursuers’ grasp, Alfred became a fugitive, seeking sanctuary in the reed beds and bogs around Athelney in Somerset. Despite the reality that much of his kingdom was overrun, he refused to give up, instead sending word that his followers should meet at the stone of his grandfather, King Egbert. Gathering them around him, he marched to meet Guthrum’s army. At Edington in Wiltshire in May 878 the two sides fought one of the decisive battles of English history. Alfred was victorious. The Vikings were routed.

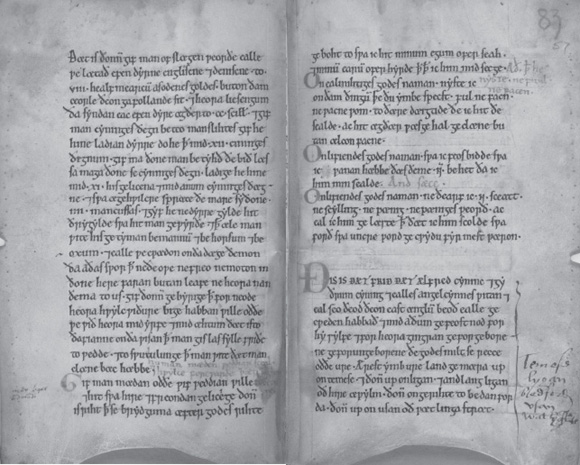

The Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum. The words describing the Saxon–Viking boundary line appear, in Old English, in the last paragraph on the right-hand side of the document (a translation appears on the facing page).

Stunned and impressed, Guthrum came to see Alfred at Aller in Somerset and in the church there a remarkable ceremony took place. Guthrum converted to Christianity. Alfred became his godfather, even raising him from the baptismal font. The two Christian leaders then spent a fortnight together at Wedmore where they drew up a peace treaty. The Vikings would hold on to their conquests in Northumbria and East Anglia (where Guthrum would rule), while agreeing to leave Wessex alone.

Although the peace did not hold, the treaty brought Alfred sufficient breathing space to strengthen both his army and his personal authority. Thus when fresh Viking attacks were made on Kent in 885, Alfred was able to see them off and enter London. He rebuilt the city on the largely abandoned site of the Roman Londinium. Sometime shortly thereafter, he renewed the treaty with Guthrum. This is the version of the treaty that survives, with London in Alfred’s domain, demarcating Anglo-Saxon from Viking-occupied England. (It can be found today at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.) As the first clause makes clear, the new boundary line ran along the Thames estuary, up the Lea, thence to Bedford, then up the Ouse and along Watling Street.

From the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum

This is the peace which King Alfred and King Guthrum and the councillors of all the English race and all the people which is in East Anglia have all agreed on and confirmed with oaths, for themselves and for their subjects, both for the living and those yet unborn, who care to have God’s grace upon ours.

First concerning our boundaries: up the Thames, and then up the Lea, and along the Lea to its source, then in a straight line to Bedford, then up the Ouse to the Watling Street. . . .

This agreement represented only a partial victory for the Anglo-Saxons. It accepted rather than challenged Viking authority over eastern and northern England, the territory that became known as the Danelaw. However, such acknowledgement was the prerequisite of containment, the real achievement of the treaty. And in containing the Viking threat behind this line, it not only gave Alfred time to build forts, construct a navy and reform his army, it also helped solidify the political unity of the non-Danelaw areas of England under the rule of the royal house of Wessex. Some of the coins minted during the remainder of Alfred’s reign proclaimed him rex Anglorum. Even if he could not really claim to be king of England, he was at least ruler of the free English. It would be for his tenth-century successors – Edward the Elder and, in particular, Athelstan – to defeat the Danelaw and unify all England under one rule.