EDWARD I’S ANGLICIZATION OF THE PRINCIPALITY OF WALES

Three sources of authority contested Wales at the commencement of the thirteenth century. The first was the English Crown. Periodic military campaigns had scoured England’s neighbour, making inroads and building strongholds without establishing total domination. The second was the Marcher lords, the descendants of Norman barons whose estates ran not only along the Welsh borderlands but also deep into southern Wales. While nominally within the English realm, these territories were essentially the fiefdoms of their barons. Marcher law, not English law, governed their inhabitants.

The third source of authority was indigenous and was exercised in the domains of the Welsh princes. There was no law of primogeniture guaranteeing the succession to the eldest son. By the end of the twelfth century, the royal houses of Powys and Deheubarth, principalities respectively of central and south-west Wales, had been weakened by internecine rivalry. However, in the north, the mountainous princely state of Gwynedd endured and became dominant. By 1257, the authority of Gwynedd’s prince, Llewelyn ap Gruffudd, stretched south from Snowdonia to embrace two-thirds of the country. A decade later, via the Treaty of Montgomery, a trade was made of token diplomatic gestures, with Henry III recognizing Llewelyn’s claim to be ‘Prince of Wales’ in return for his acknowledging the English monarch as his feudal overlord.

The ambiguous question of whose will had seniority started to resolve itself with the succession of Edward I. One of the most determined and ruthless men ever to sit on the English throne, Edward had no intention of flattering Llewelyn, who had, after all, previously sought to interfere in English politics on the side of Simon de Montfort (to whose daughter Llewelyn was betrothed). Aware of his heightening personal danger, Llewelyn refused repeated summons to do homage to Edward either at, or following, his coronation in 1274. This snub provided the perfect pretext for Edward. In 1277, he invaded Gwynedd with a mighty army swelled not only with English knights but with Llewelyn’s Welsh enemies. Losing his fertile lands in Anglesey and facing a bleak winter in the mountains, Llewelyn surrendered and finally did Edward homage at a ceremony in Worcester. His reward was to be allowed to continue in a much-reduced Gwynedd that retained Anglesey but was shorn of most of its other Welsh acquisitions. Meanwhile the English refortified their castles and administered English law in a high-handed manner guaranteed to upset Welsh sensitivities.

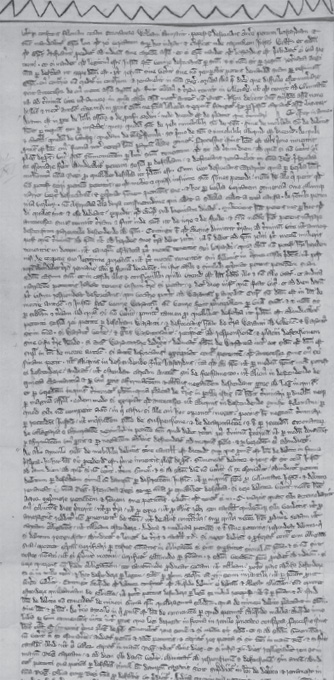

Section of the six-foot-long roll comprising the Statute of Rhuddlan. The text is in Latin.

c.1200–1240 Llywelyn ab Iorwerth (Llywelyn the Great) is Prince of Gwynedd and effective ruler of most of Wales.

1241 With the Treaty of Gwerneigron. Dafydd ap Llywelyn, Prince of Gwynedd, pledges loyalty to Henry III, cedes much of Flintshire to him and effectively relinquishes his right to the other Welsh lands claimed by his father, Llywelyn ap Iorwerth.

1246–82 Dafydd’s nephew, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (Llywelyn the Last), is Prince of Gwynedd.

1267 In the Treaty of Montgomery, Henry III acknowledges Llywelyn ap Gruffudd as Prince of Wales.

1277 Edward I invades Gwynedd, forcing Llywelyn to agree to the Treaty of Aberconwy, curtailing his authority and acknowledging Edward as his overlord.

1282–3 In the Second War of Welsh Independence, Llywelyn’s brother Dafydd rebels against Edward I.

1283 Edward I begins construction of Caernarfon, Conwy and Harlech castles.

1284 The Treaty of Rhuddlan is made.

1294–5 Madog ap Llywelyn proclaims himself Prince of Wales and leads a fresh revolt, capturing Caernarfon before suffering defeat at the Battle of Maes Moydog.

1301 Edward I revives the title of ‘Prince of Wales’ and bestows it on his son, the future Edward II.

1400–1412 Owain Glyndwr rebels.

1472 Edward IV’s Council of Wales and the Marches is convened at Ludlow.

1485 The Anglo-Welsh Henry Tudor becomes King Henry VII of England.

Welsh resentment reached breaking point in 1282, when Llewelyn’s brother Dafydd started a rebellion. Llewelyn felt compelled to come to his brother’s aid, but early successes were quickly undone. Marching into Powys, Llewelyn was killed in a skirmish while Dafydd was betrayed and handed over to the English. He was duly hanged, drawn and quartered, his head being taken and mounted on a pike next to that of his brother at the Tower of London. Rather than complete the collection, other Welsh leaders scrambled to abase themselves before Edward.

The king responded by embarking on an even more expensive castle-building programme of such grandeur that the mighty walls of Caernarfon, for instance, were modelled on those that protected Constantinople. The framework for the new political settlement was set out in the Statute of Rhuddlan in 1284. Also known as the ‘Statute of Wales’, the document dismembered Gwynedd, with Snowdonia and Anglesey passing to the English Crown. Anglesey was one of the new, English-style counties created in the north, along with Flint, Caernarfon and Merioneth. Privileged boroughs were established for the benefit of English settlers. Crimes were henceforth to be judged in the courts of English law.

Yet the Statute of Rhuddlan also established limits to anglicization in North Wales that became the template for the rest of the country. Much Welsh custom was retained. In most civil law cases, Welsh practice was tolerated alongside English common law. Only the more antiquated aspects of the native customary law were abolished.

These measures were followed, in 1301, by an imaginative act of political and symbolic appropriation. Having dispensed with the royal house of Gwynedd, Edward proclaimed his own son, the future Edward II, as Prince of Wales in a ceremony at the place of his birth, Caernarfon Castle.