The Charter of King’s College, Cambridge is depicted in the second plate section.

Where schooling was available in the fifteenth century, it was mostly offered informally through the local parish church. There, children might gain a basic acquaintance with the alphabet as well as religious instruction. At a more structured level, there were schools attached to cathedrals, of which Canterbury, Rochester and Ely pre-dated the Norman Conquest. Collegiate churches, monasteries and hospitals also founded schools. Grammar schools, offering the grounding in Latin that was deemed useful for boys (but not girls) wanting to make the study of law or theology their future profession, or to trade in Europe, were also beginning to emerge during this period.

These various forms of schooling catered primarily for local children. Less common were ‘public schools’, which were endowed foundations, open to boys drawn from all over the country. For much of the medieval period, the nobility had sent their heirs neither to school nor to university, preferring to see them develop chivalric, rather than scholastic, values within aristocratic households. From the fifteenth century onwards it was to public schools that the social elite increasingly sent their sons. Consequently, public schools came to play the foremost role in moulding and shaping the experiences of most of Britain’s political leaders, as well as a high proportion of those distinguishing themselves in many other fields of activity as well. Although not the oldest, it was Eton College, near Windsor Castle, that emerged as the greatest of these institutions. Indeed, it would be hard to think of any other school in the Western world with a comparable predominance in national life.

Despite being an independent school, Eton was founded by a monarch and its provost was originally a state appointment. Still a nine-month-old baby when he became king in 1422, the pious and ineffective Henry VI inherited the thrones of both England and France. He had effectively lost the latter by the time he was old enough to rule in his own right and would lose the former in the civil wars known as the Wars of the Roses. Mentally unstable, he was deposed and imprisoned in the Tower of London where, in 1471, he was murdered. Nonetheless, two of Britain’s most famous foundations owe their existence to him.

1096 Teaching begins at Oxford.

1209 Cambridge University is founded.

1261 A university is founded at Northampton. It is shut by royal writ in 1265.

1413 St Andrews University is founded.

1451 Glasgow University is founded.

1495 King’s College, Aberdeen, is established with university status. It merges with Marischal College (est. 1593) to formally become Aberdeen University in 1860.

1582 Edinburgh University is founded.

1592 Trinity College, Dublin, is founded.

1595 The Scottish Parliament donates a grant to erect a university at Fraserburgh. It is abandoned in 1605.

1822 Wales’s oldest degree-awarding body, St David’s College, is established at Lampeter. It becomes a constituent member of the University of Wales in 1971.

1826 University College London (UCL) is established as the first to admit students regardless of faith. It gains legal status in 1836.

1829 King’s College, London, is established for Anglican students. It becomes, with UCL, the first constituent college of the University of London in 1836.

1832 Durham University is founded. It gains its royal charter in 1837.

1845 Queen’s University, Belfast, receives its royal charter.

1880 Victoria University is established as a federal body in Manchester. Colleges in Liverpool and Leeds join it before subsequently breaking away.

1893 The University of Wales is established.

1900 Birmingham University is established and is soon followed by other ‘red-brick’ or ‘civic’ universities at Liverpool (1903), Leeds (1904), Sheffield (1905) and Bristol (1909).

Henry VI was only eighteen when he founded Eton, to provide lodging and a schooling for the sons of the wealthy and influential; but it was also endowed to educate seventy poor boys. Despite the expanding proportion of fee-paying ‘Oppidans’ in the succeeding centuries, these seventy scholars or ‘collegers’ – selected by competitive examination – remained at the core of the school with initially free and later subsidized fees.

In his designs for Eton, Henry was especially influenced by the example of the leading public school, Winchester College, which had been founded in 1382 by William of Wykeham as a ‘feeder’ for his university foundation, New College, Oxford. To provide the same continuity of learning, Henry duly founded King’s College, an institution at Cambridge to rival New College at Oxford. Like Eton, it too was to have a provost and seventy scholars, all of whom had to have attended Eton beforehand. Henry’s vision for King’s College was grandiose and in 1446 he laid the foundation stone for its chapel. It proved to be one of the wonders of late perpendicular architecture, but neither Henry nor his next four successors saw it completed. The Wars of the Roses so badly disrupted construction that it was not finished until the sixteenth century.

Although it anomalously enjoyed (until 1853) its own degree-awarding powers, King’s was a college of Cambridge University. England’s second oldest university dated from the early thirteenth century when scholars seeking to escape the violence of Oxford townsfolk decamped there. By 1400, Oxford was still the dominant institution of higher education, with perhaps 1,200 students to Cambridge’s 400. Henry VI, however, feared that Oxford was tainted with the Lollard ‘heresy’ of John Wyclif’s teaching and his decision to endow Cambridge helped redress the balance, so that by the century’s end the two universities were of roughly equal size and prestige.

Teaching was in Latin (although Greek was also taught in Oxford from the 1460s onwards) and the curriculum focused on theology, philosophy and the arts. Sixty of King’s seventy scholars studied theology, four studied canon law, two studied medicine, two astronomy and two civil law. The collegiate structure strengthened the sense of an inter-generational community, with undergraduates – who might be as young as fifteen in the sixteenth century – often living in the same buildings as their fellows. Yet despite the preponderance of students destined for holy orders, the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge were not comparable to monasteries. When the new humanist learning, with its reliance on classical Greek philosophers, took hold in the sixteenth century, the Dutch scholar Erasmus became one of those who studied at Queens’ College, Cambridge. The wealth of both universities was massively increased as a result of Henry VIII stripping the monasteries of their assets. Henry refounded what became each institution’s two grandest colleges, Christ Church at Oxford and Trinity College, Cambridge.

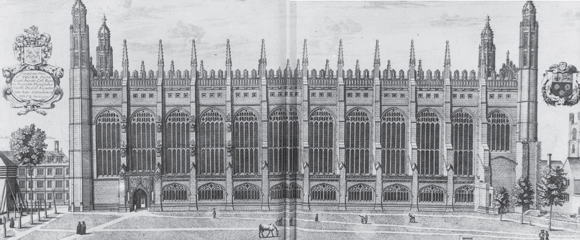

The chapel of King’s College from an engraving by David Loggan, c.1660.

Throughout its first 400 years, Eton’s curriculum was geared towards providing a classical education. Given that Latin was the language of the Church and the law, this focus was not surprising in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. By the eighteenth century however, the justification for persevering with Greek and Latin had less to do with their vocational applicability than that they offered a sufficiently difficult test of intellectual ability. Whether the classical emphasis provided sufficient training for the Cambridge Mathematics ‘tripos’ was more questionable. Despite producing Kingsmen ranging from John Harington, the Elizabethan inventor of the flushing water closet, to Robert Walpole, the first prime minister, the dependence on Eton’s gene pool certainly ossified King’s. It finally admitted its first non-Etonians in 1865 and thereafter developed a reputation for liberal, progressive and left-wing thinking.

While retaining their social exclusivity, both Oxford and Cambridge lost some of their academic rigour in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, contentedly enjoying the independence they had secured by spiralling endowment income and a virtual monopoly in producing Anglican clergymen. During this period, not only was the education offered at Edinburgh and Glasgow universities generally superior, but from 1826 competition emerged from new English foundations like University College London. However, Oxford and Cambridge restored their intellectual primacy by reforms in the mid-nineteenth century, and made their degrees available to non-Anglicans. Eton likewise reformed and broadened its curriculum, although it maintained its enduring and remarkable prominence in educating the leaders of Church and state over the succeeding 150 years. By 2010, there had been nineteen Old Etonian prime ministers, while Oxford and Cambridge had, between them, educated forty-one of Britain’s fiftyfive prime ministers. Other universities had educated only three.

Their predominance might have been readily understandable if Oxford and Cambridge were merely finishing schools for those seeking bureaucratic accreditation or parochial and worldly attainment, but they also enhanced their credentials as leading research institutions. As such, they attracted many of the world’s finest minds, supplanting in this respect the previously dominant universities of Germany and Central Europe. By the twenty-first century, some exceptionally wealthy American universities like Harvard and Yale could claim a competitive edge, while others achieved parity. Nonetheless, it was principally Cambridge academics who achieved two of the most seismic breakthroughs of the twentieth century: splitting the atom in 1932 and unravelling the structure of DNA in 1953. One Cambridge college alone – Trinity – has produced more Nobel Prize winners than the whole of France.