THE LANGUAGE OF PROTESTANT SCRIPTURE

On the eve of the Reformation, the ban on English-language versions of the Bible was still in force. The persecution of John Wyclif’s Lollard followers in the early fifteenth century stood as a warning to anyone minded to risk fresh accusations of heresy. Nevertheless, a clear opportunity to challenge authority was presented by the rising support for religious reform in Germany that followed the denunciation of Martin Luther by the imperial Diet of Worms in 1521, and the success of printing presses in disseminating dissident opinion. None were more active in mounting this challenge than those inspired and emboldened by Martin Luther’s stand against papal supremacy.

The man who decided to take the risk of producing a new, and widely available, translation of the Bible was William Tyndale. Born around 1494 in Gloucestershire, he had studied at Oxford University and was ordained into the priesthood. Significantly for his later work as a translator, he also learned Greek, possibly either under Erasmus at Cambridge or by reading Erasmus’s New Testament translation in Latin with the Greek original alongside. Given the politics of the time, Tyndale failed in his attempt to get his English-language translation printed legally in England, so he left London bound for Hamburg. While there, he may also have spent time in Wittenberg, possibly meeting Luther who had published a German-language version of the New Testament in 1522. Tyndale’s New Testament in English was finished in 1525, but an injunction disrupted its publication in Cologne. Tyndale duly moved to Worms, a centre of Lutheran activity, where the completed work was published by Peter Schoeffer.

The next stage was getting it to England and Scotland, a feat achieved by smuggling the books concealed in bales of cloth. Henry VIII’s lord chancellor, Cardinal Wolsey, led the campaign to seize and destroy the several thousand copies that reached England, in which he was largely successful. Of Schoeffer’s first print run, only one complete copy is still in existence and it was discovered in Stuttgart as recently as 1996. Two other largely complete copies also remain: one, in the British Library, is denuded solely of its title page, while the copy in the library of St Paul’s Cathedral is less comprehensive, missing seventy leaves.

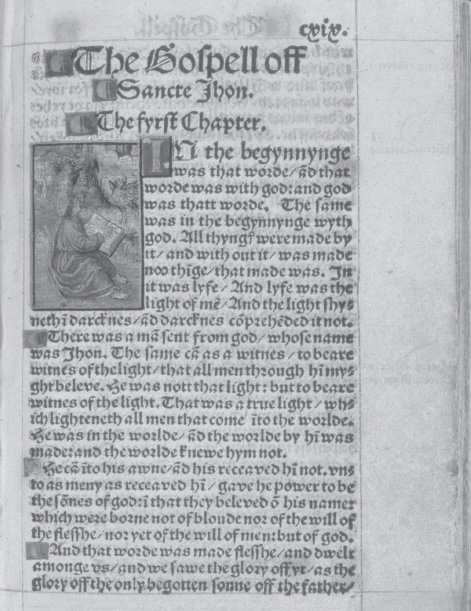

Opening page of St John’s Gospel from the first edition of Tyndale’s New Testament.

Tyndale’s New Testament differed significantly from the Wyclif Bible of the Lollards. Whereas the latter had been translated from the Latin Vulgate, Tyndale achieved greater authenticity by translating from the original Greek. Being printed, rather than handwritten, it could be produced and circulated in far larger numbers. Rough copies were soon being churned out by an enterprising printer in Antwerp. This emphasis on popularizing the word of scripture and placing it at the heart of belief was central to Protestant theology, as well as making a distinct departure from the Church of Rome’s approach. ‘I defy the Pope and all his laws,’ Tyndale proclaimed, ‘and if God spare my life, I will cause the boy that drives the plough in England to know more of the Scriptures than the Pope himself.’

Hunted by the agents of both Henry VIII and the Holy Roman Empire, Tyndale had to live and work in Worms and Antwerp undercover. Despite these conditions, his output remained formidable, turning out a succession of Protestant theological tracts while also antagonizing his powerful enemies further by condemning Henry VIII’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon. Nonetheless, his main task remained translating the rest of the Bible. He was hard at work on this, translating from the Hebrew Old Testament and had reached the end of Chronicles, when an Englishman named Henry Philips inveigled him out of his Antwerp safe house and betrayed him for money. Dragged off to Vilvoorde Castle outside Brussels, Tyndale was imprisoned for sixteen months, put on trial and found guilty of heresy, for which the punishment was death. A chain was fastened around his neck with which he was first strangled before being burned at the stake on 6 October 1536. His last words were recorded as, ‘Lord, open the king of England’s eyes.’

Although Henry VIII never adopted Lutheran beliefs, in one sense he was persuaded to permit Tyndale a posthumous victory. Only months after the translator’s death, the king licensed the first official Bible in English. Also drawing on the 1535 translation of the Lutheran Miles Coverdale, it was in reality two-thirds the work of the ‘heretic’ Tyndale. Such was both its literary and scholarly quality that Tyndale’s version shaped all subsequent translations. In particular, the committee that produced the King James Bible – the Authorized Version – in 1611 retained much of Tyndale’s language.

It would have been foolish to attempt anything else. Tyndale’s style was poetic, yet simple, giving preference to words that were Anglo-Saxon rather than French or Latin in derivation, which undoubtedly made his work more accessible to those with minimal education – the ploughboys of whom he spoke. He produced phrases that remain familiar to us almost half a millennium later: ‘fight the good fight’, ‘the spirit is willing’, ‘take up thy bed and walk’, ‘no man can serve two masters’, ‘the powers that be’. It was a style that influenced the writers of the sixteenth century, being especially influential in the work of William Shakespeare. Indeed, Tyndale’s place in the history of English literature lies not only beside his fellow theologians but alongside that of the Bard. Centuries after he met his violent fate, Tyndale is still shaping not just the way the English-speaking world praises God, but also the way that it expresses itself in day-to-day conversation.