A NATIONAL SYSTEM OF POOR RELIEF

Throughout the Middle Ages there was no state system of welfare. Rather, providing alms to the poor was regarded as a religious obligation. It was in the reign of Elizabeth I that statutory measures made the treatment of her most needy subjects a matter of national policy.

During the sixteenth century, although the country was getting no poorer, contemporaries nonetheless believed that the problem of vagrancy was becoming more acute. Various reasons for this were put forward: the inflation of the period; the process of land enclosure, which denied the lowest peasants their means of subsistence; a supposed over-reliance on the textiles industry, whose trade went through regular cycles of boom and bust. To make matters worse, the religious upheavals of the Reformation and, in particular, the dissolution of the monasteries, had undermined some of the institutions upon which the destitute had previously relied.

The first laws to be enacted were more concerned with permitting than with enforcing measures of relief. What was to prove a long debate about the supposedly ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor became a statutory concern when an Act of 1531 sought to draw a distinction between those who were indigent or homeless because of no fault of their own – such as illness or old age – and should thus be permitted to beg in their own parish, and those whose presumed fecklessness made them vagrants, who were therefore denied such rights.

Central government lacked the machinery to do much more than encourage other bodies to take the initiative. It fell to the major cities to innovate. In 1547, the City of London raised a mandatory poor rate from its citizens in order to fund poverty-alleviating schemes.

Implementing such reforms remained a matter for city and town councils until 1572 when parliamentary legislation forced local government throughout England and Wales to introduce compulsory poor rates. While punishments could still be visited upon those considered idle, the legislation relaxed the criteria by which some of the poor were deemed the agents of their own misfortune. Able-bodied paupers were to be found work to do.

In Scotland, legislation in the 1570s and 1590s firmly placed the onus of providing relief on the Church of Scotland. The ‘Kirk’ elders assessed those in need and entered their names upon parish lists. This was not quite the model adopted in England and Wales. There, the 1601 Poor Law brought together and codified the various pre-existing acts. As in Scotland, it recognized the parish as the confine of each administrating area, but in addition working alongside churchwardens were to be ‘overseers of the poor’, unpaid and appointed by justices of the peace. It was their task to assess the need and raise an appropriate poor rate from the community to cover the costs of providing for the old, to supervise work-creation schemes for the unemployed and to initiate apprenticeships for children in desperate circumstances.

Inevitably, some parishes took their statutory obligations more seriously than others. Following the letter of the law was less necessary where there was already considerable private charity or minimal poverty in the neighbourhood; and the disruptions of the Civil War weakened the state’s role in ensuring the measures were uniformly applied. There was also an assumption that the levies raised by the parish were for the parish alone and were not freely available to any passing vagrant who happened to turn up in search of benefits. Thus the 1662 Law of Settlement and Removal tried to prevent those likely to become a burden from moving to more prosperous areas (which did not necessarily want to become the destination for large numbers of vagrants) by allowing for their repatriation if they could not demonstrate they had the means for long-term self-support. The extent to which individual parishes made use of this legislation varied according to how much they felt they needed an influx of labour.

Generating work to keep the unemployed occupied proved among the greatest problems. Outdoor relief continued, although some parishes opted to build workhouses, of varying quality and congeniality. Nonetheless, the cost of poor relief spiralled at the end of the eighteenth century. The introduction from 1795 of the Speenhamland system, which sought to guarantee the poor a minimum income, proved ruinously expensive and demonstrated that parishes were often too small in size to bear it. The cost of Poor Law administration in England and Wales rose from £619,000 in 1750 to £8 million in 1818, equivalent to a charge of 13s 3d per head of population.

Be it enacted by the Authority of this present Parliament, That the Churchwardens of every Parish, and four, three or two substantial Housholders there, as shall be thought meet, having respect to the Proportion and Greatness of the Same Parish and Parishes, to be nominated yearly in Easter Week, or within one Month after Easter, under the Hand and Seal of two or more Justices of the Peace in the same County, whereof one to be of the Quorum, dwelling in or near the same Parish or Division where the same Parish doth lie, shall be called Overseers of the Poor of the same Parish : And they, or the greater Part of them, shall take order from Time to Time, by, and with the Consent of two or more such Justices of Peace as is aforesaid, for setting to work the Children of all such whose Parents shall not by the said Churchwardens and Overseers, or the greater Part of them, be thought able to keep and maintain their Children: And also for setting to work all such Persons, married or unmarried, having no Means to maintain them, and use no ordinary and daily Trade of Life to get their Living by : And also to raise weekly or otherwise [by Taxation of every Inhabitant, Parson, Vicar and other, and of every Occupier of Lands, Houses, Tithes impropriate, Propriations of Tithes, Coal-Mines, or saleable Underwoods in the said Parish, in such competent Sum and Sums of Money as they shall think fit] a convenient Stock of Flax, Hemp, Wool, Thread, Iron, and other necessary Ware and Stuff, to set the Poor on Work : And also competent Sums of Money for and towards the necessary Relief of the Lame, Impotent, Old, Blind, and such other among them being Poor, and not able to work, and also for the putting out of such Children to be apprentices, to be gathered out of the same Parish, according to the Ability of the same Parish, and to do and execute all other Things as well for the disposing of the said Stock, as otherwise concerning the Premisses, as to them shall seem convenient.

As a result, the Elizabethan assistances of doles and outdoor relief codified in 1601 were finally replaced by the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, legislation motivated by a concern that a generation of urban welfare dependency was being created. Britain was fast becoming an industrial nation and the numbers of those who might opt to become a burden was beyond the means of the parish, with its bucolic notions and limited resources. Indeed, it was assumed that many unskilled people might find the old system far more appealing than working for a living in a factory. To disabuse them of this notion, the workhouse supposedly extended a lifeline to them, on the understanding that it was a deliberate stigma, providing its inmates with an existence materially worse than that enjoyed by the struggling, but employed, poor.

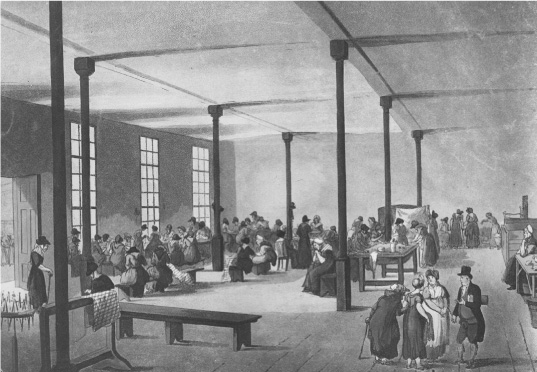

Aquatint of the St James’s parish workhouse, from the Microcosm of London, published in 1809. The figures were drawn by the famous caricaturist, Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827). The background is by Augustus Pugin (1762–1832), father of the celebrated Gothic Revival architect.

These workhouses, to which the pauperized young, old, able-bodied and infirm were brought, were made purposefully disagreeable to an extent that initially went as far as banning inmates bringing – or being given – personal possessions. Although conditions improved in the second half of the nineteenth century, the workhouse remained the last resort for many until the beginning of the twentieth century, when those able to take advantage of the introduction of old-age pensions in 1908 and national insurance sickness and unemployment benefits in 1911 were in a position to avoid them. Further undermined in the 1920s, the last institutions of the Poor Law did not survive the Second World War.