THE AUTHORIZED VERSION OF THE BIBLE IN ENGLISH

An extract from the King James Bible can be found on pages 62 and 63.

The union of the Scottish and English crowns appeared to safeguard the Protestant succession. Less immediately clear was the nature of the Protestantism to be promoted.

Mary, Queen of Scots died adhering to the Catholic faith of her parents, but her son James was brought up from the cradle by others and was, entrusted instead to the care of strict Presbyterians. He emerged into manhood as a serious, scholarly man, greatly interested in theological issues. With a strong sense of his divine right as monarch, he also rejoiced to be free of his Presbyterian schooling. Indeed, while ruling in Edinburgh, he had confronted its Presbyterian Establishment by trying to reintroduce bishops into the Church of Scotland.

Upon his becoming king in London and supreme governor of the Church of England, such episcopalianism more readily fitted in with the religious settlement of his predecessor, Elizabeth. Nonetheless, in the first years of James’s reign, different factions looked for signs that he would accommodate their views. Puritans expected greater consideration from a monarch brought up in their culture. Catholics hoped that a king whose wife was widely assumed to have privately converted to their faith, and who had commenced his reign by making peace with Spain, could prove amenable to a restoration of Roman practices.

Instead, James continued a ‘broad church’ policy intended to ensure that Anglicanism was acceptable to the majority, but in reality displeasing the hardline disciples of both Geneva and Rome for whom compromise represented a retreat from truth. Besides the role of bishops and the issue of predestination, other contentious matters included the more elaborate ceremonies and the vestments worn by Anglican clergy, which were anathema to evangelical Puritans. Imbued with an egalitarian ethos bent on reducing symbols of hierarchy between clergy and laity, they sought simplicity.

It was in the largely vain hope of reaching a lasting settlement on these and other issues that in 1604 a conference was convened at Hampton Court by the king, his bishops and other prominent theologians. There, whilst making minor changes to the liturgy, they also agreed on something that was to prove a far more significant legacy: the need for a new translation of the Bible. After the failure to prevent Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament being smuggled into Britain, a commission had been appointed charged with producing a legal version. Supervised by Miles Coverdale, this became the Great Bible of 1539. Yet neither it nor other versions, such as Archbishop Parker’s ‘Bishop’s Bible’, the Calvinist ‘Geneva Bible’ or – for underground Catholics – the ‘Douai Bible’, attracted overwhelming devotion. (The exception was in Scotland, where the Geneva Bible had become the standard text.)

Fifty-four revisers were appointed to produce the new version, among whom, at least forty-seven are known to have been actively engaged. Divided into sections, the work was undertaken by groups in Oxford, Cambridge and Westminster. The revisers were expected to follow most closely the Bishop’s Bible; but it was Tyndale’s style that remained the overwhelming influence. Nevertheless, some of his more controversial translations were reversed; for example, replacing ‘congregation’ by ‘church’ and ‘love’ by ‘charity’.

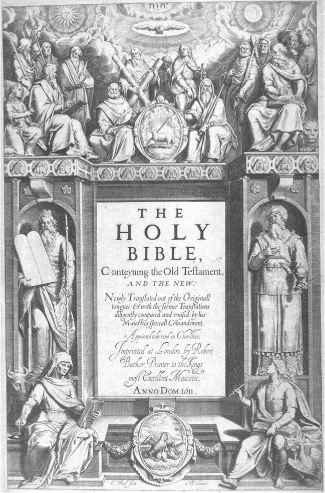

The frontispiece of the first King James Bible features the twelve apostles at the top with Matthew, Mark, Luke and John occupying each of the four corners accompanied by their symbolic animals. In the centre, Moses (left) and Aaron (right) flank the title.

The completed manuscript (subsequently lost) was bought by the king’s printer for £3,500. Dedicated to King James I, it was published in 1611 in large bound folio volumes selling for 30 shillings, with the statement ‘Appointed to be read in Churches’ on its frontispiece. The copyright was held by the Crown, which in turn licensed other printers, although, independently, the university presses of Oxford and Cambridge were also given the right to print it. Its official imprimatur ensured its familiar description as the ‘Authorized Version’. This is misleading as it never had statutory sanction. However, such was the scale of adoption that the previous versions ceased to be printed, giving it a scriptural monopoly in Protestant worship throughout the British Isles.

In its first year, two versions appeared that became known respectively as the ‘He Bible’ and the ‘She Bible’ because of the different gender usage in Ruth 3:15. Subsequent editions decided that the disputed passage should read ‘and she went into the citie’. Of the approximately 200 surviving copies of the first edition, about 150 are ‘She Bibles’. A far worse discrepancy followed in an edition of 1631, which inadvertently omitted the word ‘not’ from the seventh commandment, thereby inviting Christians to commit adultery. The edition became known as the ‘Wicked Bible’. Other minor infelicities marked out future editions, including one of 1717 that contained the ‘parable of the vinegar’ instead of ‘the vineyard’.

These printers’ errors, while beloved of antiquarian book collectors, should not detract from the accomplishment of the King James Bible. More than any other English-language translation, this was the version that endured, perpetuating Tyndale’s style and fixing the rhythm of spoken and written English for generations thereafter. It also travelled to the American colonies, helping to wed the New World to similar patterns of speech.

Such was the achievement that in Britain the King James Bible lasted without challenge for over 250 years. Only towards the end of the nineteenth century was there an attempt to tinker with revision. More comprehensive rewrites followed in the twentieth century. Whilst these latest efforts may make greater claims to biblical scholarship and easy accessibility, they have too frequently produced mundane and unmemorable prose, lacking the striking authority of the King James Bible’s stirring language and synonym. It is difficult to imagine that they will find the same enduring place in the popular consciousness.