FINANCE AND THE BANKER OF LAST RESORT

Until the beginning of the seventeenth century, Britain had no major financial sector. There was nothing to compare with the credit revolution taking place in the Dutch Republic, where the Bank of Amsterdam was founded in 1609. The goldsmiths were the nearest London came to a coherent banking community. Providing strongrooms for merchants to deposit their treasure, the goldsmiths brought together the main functions of modern banking, offering deposit and lending facilities and issuing notes redeemable for the valuables in their safe keeping.

However, they were not geared to meet the mounting credit demands of late seventeenth-century government. These became acute following the Glorious Revolution of 1688 because of William III’s determination to fight France in a war he could ill afford. Between 1690 and 1697, the state managed to raise around £28 million in revenue but spent £40 million prosecuting the war. Expedients such as the £1 million lottery loan, which offered huge cash prizes, were less a sign of the state’s ingenuity than of its failure to develop the institutions necessary to provide long-term security.

The answer to England’s financial problems was provided by a Scotsman. William Paterson (1658–1719), an adventurer who had done business in the West Indies and Holland, proposed Britain’s first incorporated joint-stock bank, to be called the Bank of England. It would solicit £1.2 million from the public, which would be lent to the government at a rate of 8 per cent interest guaranteed by Parliament. Investors of more than £500 would also get to vote for the bank’s board of management.

Investors were attracted not just by the rate of interest but also by the absence of a time limit for repayment. Potentially (and in reality), interest would continue to accrue indefinitely, becoming the National Debt. The state of its finances made the government ill placed to haggle. Among the influential persons won over by Paterson was Charles Montagu, a commissioner of the Treasury. Overcoming the opposition of the goldsmiths and other vested interests, Montagu steered the government towards supporting the legislation and the royal charter that created the Bank of England in 1694.

A SHORT HISTORY OF BRITISH BANKING

1546 Henry VIII repeals the usury laws, making lending with interest legal.

1640 Confidence in the Royal Mint is shattered by Charles I’s seizure of its gold. Growing use of the private quasi-banking facilities is offered by the goldsmiths – who fund the Parliamentarian war effort.

1659 The first surviving example of a cheque dates from this time.

1690 John Freame and Thomas Gould begin trading as Goldsmith bankers. Their firm eventually becomes Barclays Bank.

1692 Coutts & Co. is founded.

1694 The Bank of England receives its royal charter.

1695 The Bank of Scotland is founded, and the Scottish Parliament grants it a twenty-one year monopoly of public banking in Scotland.

1727 The Royal Bank of Scotland is founded.

1759 The Bank of England issues the first £10 note. The £5 note follows in 1793.

1804–9 The number of ‘country banks’ outside London increases from 470 to 800.

1811 N. M. Rothschild & Sons established as a bank in London and helps finance the war effort of Britain and her allies during the Napoleonic Wars. For much of the 19th century, Rothschild dominates the international bond market.

1821 The gold standard makes Bank of England notes convertible at a fixed weight of gold. (The gold standard was suspended in 1914 and briefly reintroduced between 1925 and 1931.)

1866 There are 154 joint-stock banks with 850 branches, and 246 private banks with 376 branches.

1870 The Bank of England assumes the right to set interest rates.

1900 There are seventy-seven joint-stock banks and only nineteen private banks left with branches. Consolidation during the Edwardian period creates the domination of the ‘Big Five’ clearing banks during the 1920s (Barclays, Lloyds, Midland, National Provincial, Westminster).

1946 The Bank of England is nationalized; sterling’s exchange rate is fixed relative to the dollar. The system breaks down in 1971, after which sterling’s exchange rate floats.

1966 Barclaycard, the first credit card, is introduced in Britain.

1968 The merger of National Provincial and Westminster banks to create ‘NatWest’ reduces the ‘Big Five’ to the ‘Big Four’.

1971 The coinage is decimalized.

1980s–90s A spate of demutualization of building societies effectively creates a string of new banks.

1986 The ‘Big Bang’ deregulation of finance markets ushers in a series of mergers and take-overs of British brokerages and merchant banks by foreign banks and restores the City of London’s financial supremacy over New York. Banking sector assets increase sevenfold between 1986 and 2006.

1995 Barings Banks – the oldest merchant bank in London – collapses after one of its derivatives traders, Nick Leeson, loses over £800 million in unauthorized speculation.

1997 The Bank of England regains operational independence but loses financial regulatory powers.

2007 £2.15 trillion of capital flows into UK financial institutions.

2008–9 The financial crisis leads to the government nationalizing some banks and taking large shares in others. Lloyds TSB rescues the debt-laden Halifax–Bank of Scotland (HBOS), but then itself needs government support.

The bank began in a rented hall in Cheapside with a staff of nineteen. Despite these modest beginnings, its attractiveness to investors was evident from the first. It was launched on 27 July 1694, and eleven days later had successfully raised the required £1.2 million. Initially, there were nearly 1,300 shareholders. Paterson, however, soon fell out with the other directors and quit. Returning to the land of his birth, he conceived and promoted the ill-fated Darien scheme to establish a colony in Central America, which wrecked the Scottish economy and humbled its leaders into seeking full economic, political and monetary union with England. Paterson then helped draw up the terms of the Treaty of Union.

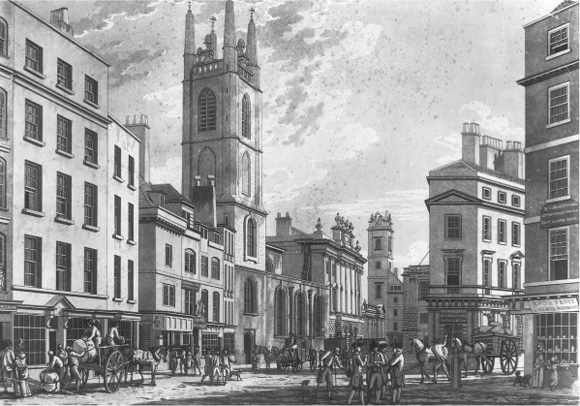

This late-eighteenth-century engraving of Threadneedle Street shows the Bank of England building shortly before its expansion – which resulted in the demolition of its neighbour, the Church of St Christopher-Le-Stocks.

Extract from The Charter of the Corporation of the Governor and Company of the Bank of England, 1694

WILLIAM and MARY, by the Grace of God, King and Queen of England, Scotland, France and Ireland, Defenders of the Faith, &c. To all to whom these Presents shall come, Greeting.

... And all and every Person and Persons, Natives or Foreigners, Bodies Politick and Corporate, who, either as original Subscribers of the said Sum of Twelve Hundred Thousand Pounds so subscribed, and not having parted with their Interests in their Subscriptions, or as Heirs, Successors, or Assignees, or by any other lawful Title derived, or to be derived from, by, or under the said original Subscribers of the said Sum of Twelve Hundred Thousand Pounds so subscribed, or any of them now have, or at any Time or Times hereafter shall have, or be entituled to any Part, Share, or Interest of or in the Principal or Capital Stock of the said Corporation, or the said yearly Fond of One Hundred Thousand Pounds, granted by the said Act of Parliament, or any Part thereof, so long as they respectively shall have any such Part, Share, or Interest therein, shall be, and be called one Body Politick and Corporate, of themselves, in Deed and in Name, by the Name of The Governor and Company of the Bank of England; and them by that Name, one Body Politick and Corporate, in Deed and in Name, We do, for Us, our Heirs, and Successors, make, create, erect, establish, and confirm for ever, by these Presents, and by the same Name, they and their Successors shall have perpetual Succession, and shall and may have and use a Common Seal, for the Use, Business, or Affairs of the said Body Politick and Corporate, and their Successors, with Power to break, alter, and to make anew their Seal from Time to Time, at their Pleasure, and as they shall see Cause. And by the same Name, they and their Successors in all Times coming, shall be able and capable in Law, to have, take, purchase, receive, hold, keep, possess, enjoy, and retain to them and their Successors, any Manors, Messuages, Lands, Rents, Tenements, Liberties, Privileges, Franchises, Hereditaments, and Possessions whatsoever, and of what Kind, Nature, or Quality soever; ... And we do hereby for Us, our Heirs and Successors, declare, limit, direct and appoint, that the aforesaid Sum of Twelve Hundred Thousand Pounds so subscribed as aforesaid, shall be, and be called, accepted, esteemed, reputed and taken, The Common Capital and Principal Stock of the Corporation hereby constituted.

Rivals like the Land Bank were quickly seen off and while small provincial private banks issued their own notes, the Bank of England’s notes were subsequently given a monopoly in the London area where their promise to pay the ‘bearer’ (not just the original depositor) made them easily exchangeable units of currency. By the 1930s the Bank of England had gained a monopoly on producing all England’s banknotes (Scottish and Northern Irish banks continued to print notes north of the border and in Ulster). Successive notes bore the image of Britannia. The decision to follow the ancient practice of the coinage and put the monarch’s face on the notes began only as late as 1960.

Although the Bank of England was not created as the state’s central bank, this is what it became. During the eighteenth century, four-fifths of its business was government-related. It looked after government department accounts and managed a National Debt that increased from £12 million in 1700 to £850 million by 1815. As early as 1781, the prime minister, Lord North, described the bank as ‘from long habit and usage of many years . . . a part of the constitution’. The bank’s reputation for financial security was acknowledged in a popular catchphrase, ‘as safe as the Bank of England’, while currency stability created in between the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the onset of the First World War (by a gold standard that valued the pound sterling to a fixed quantity of gold) also helped London emerge as the world’s financial centre.

It was as this age was passing, during the inter-war period, that the Bank of England completed its long process of becoming Britain’s central bank and lender of last resort. It had been setting the country’s interest rates since 1870. How little difference its nationalization in 1946 initially made may be judged by the fact that the same board was retained after the state formally took control. The collapse of an international system of fixed currency exchanges in 1971, and a belief that Treasury interference in interest-rate policy involved more political than economic calculation, led to the bank regaining operational independence in 1997. At the same time, it lost its regulatory role over the City to a new Financial Services Authority. This proved controversial and following the financial crisis of 2008–9, the incoming coalition government in 2010 set about restoring some of the FSA’s regulatory powers to the bank.